When Christopher Plummer died on February 5, the world mourned him. Those who worked with him paid tribute to his warmth, his talent, and his Renaissance flexibility ÔÇö director Des McAnuff (who was to direct him in a King Lear film after the pandemic abated) remembered him sketching little masterpieces in rehearsal; co-star Chris Evans recalled his piano improvisations on set. And for critics, the 91-year-old was a fallen redwood. Matt Zoller Seitz wrote movingly about PlummerÔÇÖs capacity for reinvention and collaboration onscreen, and Jesse Green recalled his forceful, graceful work onstage.

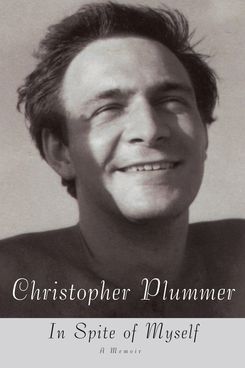

But there was yet another string to PlummerÔÇÖs bow: world-class dish. Although his gossipy 2008 autobiography In Spite of Myself ends in a rather quiet cul-de-sac, the rip-roaring center of the book details every variety of mayhem a gorgeous actor could get up to in the 20th century. In obituaries and reminiscences, writers tend to focus on PlummerÔÇÖs swinginÔÇÖ ÔÇÖ60s life ÔÇö we remember him as Captain Von Trapp, so we like to contrast GeorgÔÇÖs martinet bearing with his louche real life, like falling down an elevator shaft while sauced. But PlummerÔÇÖs autobiography emphasizes the way he also felt out of joint with his time. He saw everything through the lens of theater: he worshipped the actors of a generation before, and he was proudest and most passionate about his work on stage. So while we can collect his top ten movie performances, the greater, un-capturable part of his work vanished when the curtain went down. Lucky for us, he wrote about it. On Twitter, the New Yorker writer Rachel Syme shared a few snippets from the memoir, including the slyest swipes at Laurence Olivier. But having read the 656-page book this week, I can assure you, the whole thing is highlights.

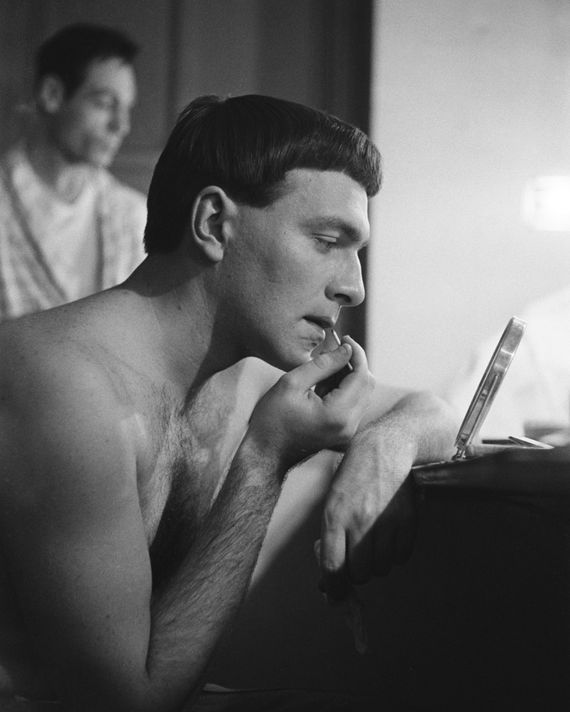

An erotic education

We begin in Senneville, near Montreal, in a scene of dwindling grandeur. PlummerÔÇÖs family background contains generations of Canadian wealth and power, though he and his mother actually have very little money. HeÔÇÖs transfixed by both the Chekhovian nature of this twilight-of-the-classes and his own, boisterous teenagerhood in the ÔÇÖ40s, which he spent at bars and bo├«tes full of down-on-their-luck decadents. In one striking scene, Plummer describes a blonde habitu├® who sits tipsy and naked under her furs on a barstool, occasionally dropping her coat to shock the clientele. He seems to have lived in a pulp novel, or at least the cover of one. Still young, he yearns to be one of these beautiful derelicts, so he ripens and rots. When heÔÇÖs 19, heÔÇÖs already debauched ÔÇö too blind drunk to go on stage as Oedipus.

The Bermuda interlude

Despite his unsteadiness, he manages to get a job as the young male lead in a repertory company at the Bermudiana Theater in Bermuda. The little troupe (which includes a very young Marian Seldes, who would become the grande dame of New York theater) is beefed up periodically with slightly used stars, like Burgess Meredith, Franchot Tone, and star of the early talkies, Ruth Chatterton. These dimming luminaries would pop in for a show or two and then leave the young company to their mischief. At this point, PlummerÔÇÖs writing has basically turned into a Penthouse Forum letter ÔÇö in a production of The Petrified Forest, he makes out with a bare-breasted stage manager, who sits just out of sight of the audience, feeding him kisses and lines. In the far narrative background, he shows us the story of a Black hotel worker falsely accused of rape by another of his bookÔÇÖs many femme fatales, but his own whirring life whisks him up and away, Bermuda dropping below the airplaneÔÇÖs wing.

His own worst agent

As he made a name for himself as an actor with an ear for verse, he found work on tours with the last of the great actress-managers and divas, goddesses like Katherine Cornell, Eva Le Gallienne, and Judith Anderson. He played callow youth to their imperious grandeur, and his rapscallionery ÔÇö giggling onstage, being too drunk for rehearsal ÔÇö made them alternately scold and mother him. At one point, while understudying Tyrone Power in The Dark Is Light Enough, Plummer had lunch with a critic, pitched himself as a better actor for PowerÔÇÖs part, then acted out the entire role at the table. His own happiest era seems to have been the ÔÇÖ50s, before his megastardom, when he would pop up to OntarioÔÇÖs blossoming Stratford Festival, then return to New York to make his living in live television. Many of his performances in plays were in fact done for live TV, which ÔÇö impossible to believe now ÔÇö showed hundreds of serious dramas with stars like Jos├® Ferrer (Plummer played Christian to FerrerÔÇÖs Cyrano) and Sylvia Sidney.

All honorable men

In these days, Plummer sees himself as a character in a New York full of characters, whether George C. Scott dripping blood on his doorstep after a fight, or the policeman who leads his horse up to the bar at SardiÔÇÖs. (It turns out you can make him drink.) Plummer marries, but he spends zero time talking about his baby daughter, Amanda, whom he barely sees until sheÔÇÖs grown and a Tony-nominated actress herself. Instead, thereÔÇÖs a terrific chapter on a cursed production of Julius Caesar in Connecticut, starring a weird assortment of actors. Plummer was playing Mark Antony, when one night, in a temper after a bad review, Jack Palance (playing Cassius) refused to leave him alone on stage for his soliloquy. As Mark Antony vamped, hoping for solitude, Cassius hissed with rage, straddled CaesarÔÇÖs corpse, tore off his own velvet cape, dropped his sword and buckler down a set of stairs, and raged off into the wings. When Plummer later tells a story of another extended, Three Stooges-esque exit (this one a HamletÔÇÖs Father who clattered through a set like a runaway garbage can), your suspicions rise. But perhaps such things really happen. Anyway, they should.

Do not, actually, climb every mountain

Eventually, buoyed by several triumphs at Stratford (where William Shatner was once his understudy), heÔÇÖs wafted over to London, where heÔÇÖs a bonafide star. The recently christened Royal Shakespeare Company instantly welcomes him with plum parts, joining early members like Vanessa Redgrave, Peter OÔÇÖToole, Diana Rigg, and Judi Dench. (You can still see him star in the 1964 Hamlet, shot for the BBC on location in Elsinore, on YouTube, which gives you an understanding of what a wonderfully listening actor he was onstage.) His career explodes with The Sound of Music, but heÔÇÖs miserable ÔÇö ÔÇ£Probably due to an excessive number of nuns in the cast, there was ÔǪ an atmosphere of overreverence which irritated me no end.ÔÇØ He does, though, enjoy telling us that in the movieÔÇÖs climactic final scene, the cast were in fact climbing a hill next to the ruins of Hermann G├ÂringÔÇÖs ÔÇ£EagleÔÇÖs NestÔÇØ and just over the slope from HitlerÔÇÖs private lair.

You common cry of curs

Many of PlummerÔÇÖs obituaries have mentioned his 1971 dismissal from a National Theatre Coriolanus by vote of the cast. Thanks to placement (usually right after something about his carousing), these mentions add to a sense that his appetites made him self-destructive. In fact, it was a poorly handled disagreement over whether the NTÔÇÖs artistic director Laurence Olivier had hired him to play ShakespeareÔÇÖs version of the play or BrechtÔÇÖs. The theater wanted to do a leftist interpretation; Plummer didnÔÇÖt want the rabble getting more sympathy than the aristocratic general. It did not necessarily help that he had arrived at the first read-through in a chauffeured Rolls Royce. Everyone tried to out-snob each other, though PlummerÔÇÖs devastating set down of the National TheatreÔÇÖs dramaturg Kenneth Tynan (ÔÇ£his only contribution to society was Oh! Calcutta!, an inferior sexical performed by numerous unknowns in the altogetherÔÇØ) wins the point. ÔÇ£SexicalÔÇØ is definitive.

Written on water

At this first peak of his career, Plummer alternated between the theater (a Tony award-winning Cyrano on Broadway) and film epics like WaterlooÔÇöthe first type of art vanishes once theyÔÇÖre performed, the second havenÔÇÖt aged well. A pall hangs over this part of his life; he seems less heedless and joyful now that heÔÇÖs a megastar. In The Royal Hunt of the Sun on Broadway, he was bizarrely heckled by a drunken Gary Merrill, Bette DavisÔÇÖs husband, then stalked by a female fan. He does, though, seem thrilled to head to Greece to play the lead in a filmed-on-location Oedipus Rex. (Orson Welles played Tiresias, and a stunned looking Donald Sutherland was the Chorus Leader.) This film is also on YouTube, but itÔÇÖs not exactly wonderful. ItÔÇÖs unfair: the acting triumphs were written on water, while embarrassments were fixed on magnetic tape. The ÔÇÖ80s and ÔÇÖ90s also saw him hit theatrical heights, productions like his Othello with James Earl Jones on Broadway, another Tony for his solo piece about John Barrymore. These lofty offerings are wildly different from his screen work at the time, but itÔÇÖs that video that lasts.

One last string to the bow

Of course we know that he was ÔÇ£rediscoveredÔÇØ by film directors, and that in 1999, The Insider jumpstarted two decades of incredible film roles. But by this point, heÔÇÖs devoting his most passionate writing to his house, his dogs, his beloved third wife. ThatÔÇÖs because the memoir is really a telescope, its focus sharpest when looking far away. Plummer isnÔÇÖt confessional ÔÇö he doesnÔÇÖt spend much time on the relationship with either his father (who he met only a few times) or his daughter. But he does write beautifully about things that vanish, particularly live performance. Plummer desperately wants us to have seen the performances he has, particularly since many of the actors he has known have been preserved in films that donÔÇÖt do them justice. Between the gossipy bits, he casts his mind back 50 years to recall some elegant piece of business performed by a man now remembered for The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show, or lauds Canadian tragedian John Colicos, now more famous for Battlestar Galactica. He does not say outright that that cultural memory will work the same way for him, that the ÔÇ£permanent recordÔÇØ will tell only a partial story. But he doesnÔÇÖt need to. He was a man who listened deeply and could explain what he heard. To all his many roles, he adds a few more ÔÇö critic, witness, recording angel.