The best trick Promising Young Woman plays occurs in the very first scene. Cassie (Carey Mulligan) is falling down drunk in a bar while a group of men leer nearby. Eventually, one of them approaches, ostensibly to help her get home safely, but we watch as he gradually ushers her back to his place, onto his bed. As he begins to undress her, she comes to, revealing she has been stone-cold sober the whole time. It’s a squirm-inducing scene, made all the more uncomfortable by the fact that the guy in question is not played by some unknown character actor but by Adam Brody, an actor who, since his stint on The O.C., has been synonymous with good-hearted boys next door.

Seth Cohen, how could you?

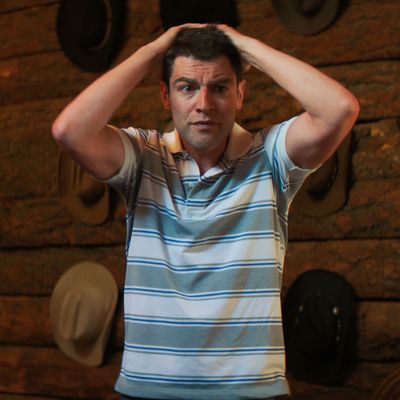

It’s not just Brody. Turns out, almost every terrible man in the film is played by a beloved actor from a renowned television show of the recent past. The doofus whose fedora barely disguises his misogyny? That’s Sam Richardson, best known as the lovable Richard Splett in Veep. The self-proclaimed nice guy who provides our glimpse into Cassie’s revenge scheme? That’s Christopher “McLovin” Mintz-Plasse (who, yes, did break out in a movie, but he has also been on TV, so it counts). And when Cassie crashes a bachelor party for the guys who ruined her friend’s life, she comes up against two TV crushes from decades past: Max Greenfield, who played the scene-stealing himbo Schmidt on New Girl, and Chris Lowell, Veronica Mars’ lovelorn Piz.

As you might suspect, this meta-casting was not a coincidence. According to the film’s casting directors, it was a deliberate ploy by director-writer Emerald Fennell. “She knew exactly how to play with audience expectation about who the good guy is and who’s not,” says Mary Vernieu of Betty Mae, Inc., a Los Angeles–based casting agency. That the scumbags are played by actors with friendly, familiar faces underlines one of the movie’s arguments: Anyone can be an abuser, even cute, nerdy guys who are obsessed with Death Cab or ones who live in a hip downtown loft with their adorkable friends.

Fennell’s collaborators describe her as a director with a particular facility for actors, perhaps because she had been one herself. “She knew exactly what she wanted, and that’s always a pleasure,” says Vernieu. “Some directors don’t know what they want and then you’re just shooting in the dark.” Accordingly, the film’s casting process was much shorter than an average film. With Fennell’s very specific idea about what and who would work, the casting directors could search through a smaller pool of performers. A process that on other films can drag on for the better part of a year took only two months here.

As for the type of actor Fennell wanted, “it wasn’t the usual suspects,” says Betty Mae’s Lindsay Graham (who is not a senator). Take Bo Burnham, a comedian who had recently transitioned to directing with Eighth Grade. Though Burnham had appeared in films like Rough Night, he wasn’t any studio’s first choice for a romantic lead. “That outside-the-box idea was something she was really excited about,” says Vernieu. “And that excites us, because we love casting outside the box.”

Thus all the famous TV nice guys. Most of them didn’t audition. Instead, the casting directors set up a series of meetings in which Fennell could get to know prospective actors and see whether they vibed on the film’s unique frequency: a comedy that goes to some uncomfortable places while still staying light on its feet.

For Brody’s character, initial impressions were key. He’s the first man Cassie encounters, and the nice-guy baggage Brody brings with him was a key part of introducing the movie’s premise. “With all that we know about him from his past work, he was perfect,” says Vernieu. “He really does look like an all-American guy who might be a knight in shining armor.” The script plays up this tension even more: The Brody character (then called Jez) is the token nice guy among his buddies, the one who makes a point of defending women. Though those notes have been sanded down in the finished film, there’s still a part of Brody’s presence that retains the audience’s sympathy. As Fennell’s screenplay notes when the character nervously cleans up his apartment upon Cassie’s arrival, “This could be the start of any dude-skewed romance.”

While Brody’s character has to maintain a hint of plausible deniability, Richardson, as his sexist friend, is a buffoon. “The film is very dark, but you have to find that lightness, and Sam found those layers,” says Graham. Richardson trained at the Second City, and his comedy background balanced out a character who plays particularly vile on the page, keeping the film from tipping into an outright drama. So too did Greenfield, as an amoral best man who’s suspiciously good at cleaning up crime scenes. “He’s very funny,” says Vernieu. “He’s got a real likability with underlying sarcasm.”

For the film’s first act, exactly what Cassie does to the guys she picks up remains a mystery. (Fennell feints at violence before we realize the red liquid dripping down the character’s leg is actually just ketchup.) The film only shows Cassie’s regular routine in full once, when she interrupts a creep played by Mintz-Plasse before he can stick his hands up her skirt. The scene cracks with tension — what exactly is she going to do to him, or him to her? — and the choice of Mintz-Plasse, who hasn’t appeared in a movie since his cameo in The Disaster Artist, only adds to the suspense. “We haven’t seen Christopher in a movie for a while,” says Vernieu. “So in a funny way, you didn’t know what to expect there. You have no idea where it’s going to go.” McLovin’s a little older now, a little more bitter. Who knows what he’s capable of?

But of all the guys in the ensemble, the hardest to find was Al, the one who committed the crime that Cassie’s avenging. Casting associate Patty Rhinehart calls him “the last piece of the puzzle.” The character’s reputation is built up for nearly the entire movie before we finally see him, and when he does appear, it’s a tricky role to play: a man who embodies both the cruelty and the banality of the patriarchy. “We’ve found, in casting movies like this, that some actors that you think are going to nail it don’t, because it’s a fine line to walk in those moments,” says Graham. “It’s not an easy tone to portray.”

Then Lowell sent in a tape. “We just knew it was him,” says Vernieu. “He was able to strike the balance between having the charisma but also having that underlying darkness.” You can see how he’d be able to skate freely through life, but you also buy that he’s capable of the terrible things we’ve heard about. When Al crosses a grave moral line, he comes off not as a sneering villain but merely a desperate, weak man.

Throughout the process, the casting directors say their job was made much simpler by Fennell’s buzzy script. “Everybody wanted to be part of the film,” says Graham. “It was an embarrassment of riches.”