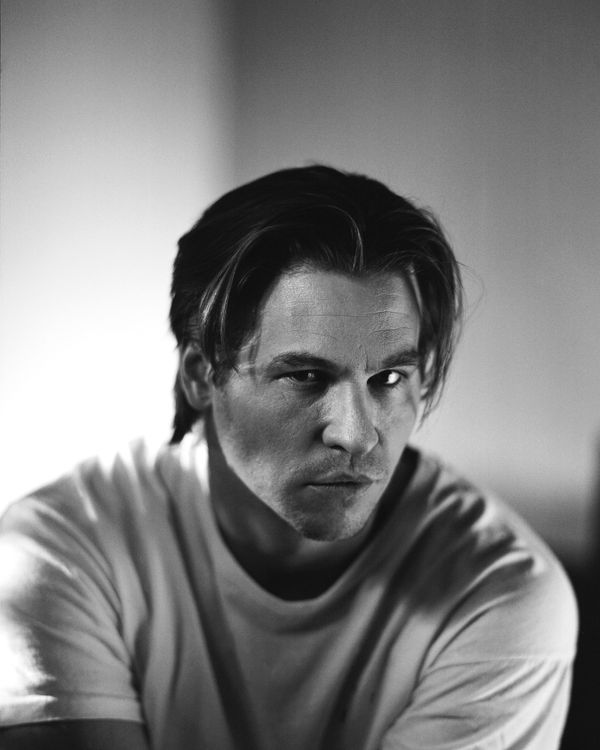

Val Kilmer has been appearing in other people’s films for nearly 40 years, but, as is revealed in his new documentary, Val, he’s been filming himself for even longer. He started shooting video as a kid on his father’s California ranch, making 16mm remakes and parodies of his favorite movies with his late brother Wesley. Kilmer shot through his alternatively transcendent and traumatic experiences playing Doc Holliday, Batman, Jim Morrison, and Iceman; he shot through the rosy glow of the beginnings of his marriage to Joanne Whalley and the protracted crumbling of it; he shot through his 2017 diagnosis of throat cancer and the subsequent treatments that rendered him almost unable to speak; and he shot through his obsession with and efforts to turn his own version of Mark Twain’s life story into a theater show and, hopefully, someday, a completed film.

A few years ago, Kilmer joined forces with directors and editors Leo Scott and Ting Po and began sifting through the thousands of hours of footage Kilmer had amassed. What amounted is something singular and fascinating: a look at the actor’s far-famed, occasionally tumultuous career and personal life, seen almost entirely though his eyes. Val, which premieres at Cannes Film Festival on Wednesday, is a genuinely surprising and strange movie that vacillates between emotional extremes at an almost minute-by-minute pace. We see grainy, kooky footage of Val and Wesley as a slaphappy kid before learning (via Kilmer’s son Jack’s voice-over) that the actor’s brother drowned in their family’s hot tub after an epileptic fit. We hear Kilmer briefly addressing persistent rumors that he was “difficult” or “hard to work with” on various film sets while watching footage of him on those same sets. (A highlight: his attempt to shoot the shit with a forlorn-looking Marlon Brando — his lifelong hero — on the set of the famously doomed Island of Dr. Moreau.) We see him finding his way at Juilliard as a raw-talent 17-year-old and realizing, in an early Off Broadway play where he’s pushed down the call sheet, that he’s desperate to be taken seriously. Cue parts in the less-than-serious Top Gun and the spy spoof Top Secret! and eventually Batman, which required a suit that prohibited him from emoting — or even breathing, really — the way he needed to. He flies to fan conventions and screenings for his now most popular films, waving and signing autographs, while in voice-over explaining that he expects to feel embarrassed at such events, promoting a long-gone version of himself.

Kilmer’s guilelessness in recounting his life so directly, without interruption, is disarming and perhaps a bit obfuscatory. There are few other voices weighing in with their version of events here; we know we’re getting Kilmer’s take on everything and that aspects have been left out in his retelling. (Was Kilmer, for example, as Joel Schumacher put it, “psychotic” on the set of Batman? Or was Kilmer just losing too much oxygen?) But objectivity was never the goal. The documentary is now Kilmer’s best, and maybe only, way of communicating how it felt and still feels to be him, a man whose entire life was centered around expressing something urgently to an audience and who now has to press a button on his throat to talk. This is, in part, why our interview about the film had to take place over email — a medium through which it’s nearly impossible to stage an uninterrupted conversation. Ahead of his film’s premiere, Kilmer and I traded questions and answers back and forth for a few days. Though he let me in a little bit, it’s clear that he’s much happier letting his 16mms speak for him.

How long have you been filming yourself exactly?

I started telling stories with my brothers when we were just a couple Chatsworth [the suburb of Los Angeles] kids. I was the first of my friends to have a camera.

Did you always intend to turn this footage into a doc about your life?

I always felt that the stories behind the stories we were telling would make a great film. Reading between the lines chronicling the life of an actor.

But were you confident, even as a kid, that you would become an actor people make documentaries about? That insinuates a real level of self-assurance at an early age.

I didn’t know that I was going to be an actor that people would make documentaries about, but I knew I was an actor.

What was the process like in terms of putting this all together? How did you get involved with Leo and Ting, and what sort of role did they play in going through the footage and creating a shape for the film?

Leo Scott came to the States about a decade back and has been essential in documenting my exploration of Mark Twain as the narrator of what it means to be a real American. Leo is a truly gifted editor and our sensibilities spoke to each other. He traveled with me as we workshopped the show, spending late nights and many years archiving some-200 boxes of 8mm, Super 8, 16mm film and video. My producing partners were always pushing for me to tell my story. Leo brought on Ting and created the most glorious sizzle reel. It was as if we worked on it for decades (which in many ways, we had). Ting has a way of bringing the past and present together in seamless transition. Leo’s artful precision, Ting’s Oscar-winning talents, and my tenacity seem to form the perfect diamond.

So what was the goal for you with this film? A press release for it referred to you as “one of Hollywood’s most mercurial and/or misunderstood actors,” and I’m curious if you personally feel that way — like you’re mercurial or misunderstood by people.

Life is a spiritual journey and my goal is to live in the moment. Being present-minded has taken me to places of the extreme, both light and dark. I’ve always had an opinion about the stories we were telling and this often led to a healthy amount of creative tension. But things aren’t always adversarial. I’ve had wonderful collaborations with filmmakers.

In the doc, you do touch briefly on this idea of you being perceived as a “difficult” actor to work with.

I’ve always approached what I do very seriously and I understand that sometimes that’s perceived as being difficult.

You also struggle with the demands of mainstream fame throughout Val, specifically the way that it contrasts directly with or even hinders this desire to be a more serious actor.

I was trained as a stage actor — I saw myself that way and I still do. But I love film. The business works a certain way; sometimes I did it well, sometimes I did not. As I prepared my Twain [show] for Broadway, my eye and my vision was actually always on the film version. I’ve grown, I’ve changed, I’ve stayed the same. I’m as excited about a great performance today as I was the day I discovered [Marlon] Brando.

Early on in the film, you discuss how Sean Penn and Kevin Bacon took the bigger roles in an Off Broadway production you were in, pushing you down to third on the call sheet. You say, “Not all characters are created equal, and it was clear to me that my mission was to chase down roles that would transform me.” Which roles in your career ended up doing that for you?

Hamlet, Doc Holliday, Mark Twain, Jim Morrison.

For Jim Morrison, you spent a year living almost entirely as him. Does transformation always require that level of commitment for you?

Manifesting a character is all part of the spiritual process. I attack roles like I attack life — with purpose. Twain was a monster to tackle. Took a full year to workshop it daily.

Do you regret taking any roles?

No.

I wonder specifically about Batman, which you have spoken about as a restrictive rather than transformative experience. Has your opinion of your performance in that movie changed at all over time?

No.

You said you originally didn’t want to do Top Gun because it was “silly” and “war-mongering.” What about your role in the sequel made you want to be a part of it?

Tom and I picked up just where we left off. The reunion felt great. As far as the film’s plot goes, I’m sworn to secrecy.

Val sort of skates around the last chunk of your career — Snowman, Song to Song. Any reason for that?

The last 20 years of my life have been wholly consumed by the story of Mark Twain and Mary Baker Eddy. My one-man show Citizen Twain was simply a “rehearsal” for the film that I’ve been working on producing. There are projects around this work that I am working on as we speak.

When is Mark Twain Dreams of the Resurrection, the animated film you produced, coming out?

It’s a work in progress. No release date as of yet.

What’s the most surprising piece of footage you found in the process of compiling Val? Or the most difficult to watch?

My little brother’s films. Wesley — he was a genius. My mother also passed during the shooting of [Val] and there is some beautiful footage [from that time]. Ting and Leo’s mastery brought her to life. And anything with Marlon. I loved him.

How did you determine how vulnerable and honest to get within the context of this documentary? Because there are some really personal moments in here: you mourning your mother’s death, you speaking about a custody arrangement for your kids over the phone during your divorce proceedings.

You don’t decide if you’re going to be vulnerable and honest, you just simply are.

Was there any aspect of your life you ultimately decided not to share in this doc?

I’ve made films that paid for my ranch, my one-man show … I’m not ashamed of that. It’s just not that interesting.

Watching your younger self, what would you say to him, if you could reach back in time?

Slow down, my friend. Waste more time. Pray more.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More From France

- Jeremy Strong Practiced His Dad Jokes on Anne Hathaway

- Nitram Dares You Not to Look Away

- Colin Farrell Gets His Ex Machina Dance Moment at Cannes