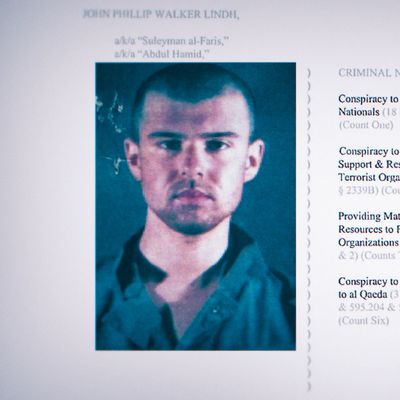

Directed by Greg Barker, the riveting new Showtime documentary Detainee 001 revisits the story of once-infamous ÔÇ£American TalibanÔÇØ John Walker Lindh, a young man from California who had converted to Islam as a teen and joined the Taliban prior to 9/11, only to wind up wounded and detained by U.S. forces in late 2001. At the time of his capture, Lindh was immediately held up as a traitor, his gaunt, dirt-covered face plastered across the worldÔÇÖs newspapers. As BarkerÔÇÖs film suggests, however, his mistreatment at the hands of the U.S. ÔÇö stripped naked, blindfolded, bound to a stretcher, confined to a shipping container, with soldiers posing for photos next to him ÔÇö was a harbinger of the prisoner-abuse scandals that would later emerge from places like Abu Ghraib. (The term ÔÇ£take the gloves offÔÇØ was reportedly originally used by Donald RumsfeldÔÇÖs office to instruct those interrogating Lindh.)

Lindh was held in federal prison until his release in 2019. Detainee 001 is less about his experiences over the past two decades as it is a suspenseful and disturbing account of his initial capture, using the surprisingly lengthy interview he gave at the time ÔÇö only brief snippets of which were seen on the news ÔÇö to help re-create both his journey and the deadly Qala-i-Jangi prison uprising during which he was captured. For Barker, the film marks the culmination of four years of effort, and represents another chapter in his ongoing chronicle of the world after 9/11, which includes the documentaries Manhunt: The Inside Story of the Hunt for Bin Laden, Koran by Heart, The Thread, The Longest War, and Sergio. (Barker also co-wrote the latterÔÇÖs narrative namesake, which starred Ana de Armas and Wagner Moura and was released by Netflix last year.) We spoke about his efforts to interview Lindh, the ongoing importance of this story, and why he was so determined to tell it after so many of the people he approached about it refused to talk.

I was really surprised by the approach you took in Detainee 001 ÔÇö using John Walker LindhÔÇÖs initial interview from his capture to weave a present-tense story about him and the Qala-i-Jangi prison uprising of 2001.┬á

I have to be honest with you: IÔÇÖve never encountered a subject where so few people wanted to talk. And this is from all sides ÔÇö from him, his family, his lawyers, to the government officials involved at the time, to soldiers who interacted with him. I even got the name of the doctor on the aircraft carrier who treated his wounds. Nobody wanted to talk.

Why do you think that is?

Because I think nobody comes out looking good, and nobodyÔÇÖs proud of how they acted. And because of that, on a practical level, the normal journalistic account of this, the forensic ticktock of when did the abuse begin and what actually happened, was almost impossible to tell ÔÇö just because nobody would cooperate. Of course, that just made me more determined to tell it in some way. As we hit a brick wall in one way, it actually was very freeing. I had watched a lot of the footage [of LindhÔÇÖs post-capture interview]. As it happens, I had [a copy of] it in my personal collection, and didnÔÇÖt quite realize what I had, until I went back and looked at it. ItÔÇÖs incredible. Then I realized that we could make this kind of experiential film about this moment in time.

I never realized how long the full interview was. I remember seeing brief clips on the news at the time of his capture.

That interview that happens with John, as heÔÇÖs just lived through this horrific time in the prison, is the most heÔÇÖs ever said, probably, outside of a courtroom. There was a very narrative, filmic way into the story, just through this material, letting us unpack slowly and go into this world. These are all journeys, these films. You donÔÇÖt quite know where youÔÇÖre going to end up.

Tell me about the efforts you made to interview John Walker Lindh. Did you ultimately have any kind of interaction with him or his family?

With his family and lawyers. TheyÔÇÖre up in San Francisco. I went up to see them quite a bit. They were asking him, briefing him on our discussions, while he was in prison. Because of the unit in which he was held in the federal prison, their communications with him were quite limited. The dad I spent a fair amount of time with, in person. It always seemed like an interview was about to happen. I never quite got a handle on whether they were just being nice and stonewalling. Going in, I was very clear with them about who we were talking to and my objectives. I do not have an agenda with this film.

Then, after his release, it was always a no. In fact, several avenues of people who were with him in prison, who we got in touch with, who wanted to speak and said, ÔÇ£Sounds good,ÔÇØ they kind of all dried up and disappeared. Which tells you something. But again, it wasnÔÇÖt just John and his family. It was the soldiers who you see interacting with him [around the time of his capture]. I actually knew a lot of them through other projects. It should have been an easy ask, and none of them would go on-camera. Across the board, there was this weird sense of, ÔÇ£Would you just stop making this film and let us get on with our lives? Please donÔÇÖt tell this story again.ÔÇØ

So why did you want to tell this story, despite all these roadblocks?

IÔÇÖm interested in these origin stories, about how our world was shaped, particularly in these first months after 9/11. On a policy level, itÔÇÖs an inflection point. ItÔÇÖs when the Bush administration decided that the legal system is not reliable. One of the reasons for the plea bargain is that the defense was about to put soldiers on the stand, special operations guys, who were by then training to go into Iraq, who were going to have to testify about the mistreatment and when that began. Nope, they didnÔÇÖt want that. That is when we closed up our justice system and said, ÔÇ£Okay, this all needs to happen in quiet.ÔÇØ Which leads to Abu Ghraib, black sites, Guantanamo, all of that. You can feel it. Again, I canÔÇÖt prove it, but in the research and the way people talk, thatÔÇÖs what happened. So, thereÔÇÖs that.

One of the things that really has driven a lot of my work since 9/11 is trying to claw back some empathy, even for people who we might find offensive or disagree with. I think its corroded our whole national discourse, not just about the war on terror, or whatever you want to call it. I think Lindhs story and the vilification that he was subject to  regardless of what you think of his journey and all of that, which is a separate question  the way it was covered in the media and talked about by our leaders was just  this is when empathy for the other, or the other within, just completely went out the window. He became the enemy.

But also, itÔÇÖs just an amazing story. Particularly with the perspective of time, looking back at this forgotten battle, this forgotten guy. It also tells a bigger story that relates to the world weÔÇÖve created today.

Speaking of empathy, you get into this a little bit in the film as well, but heÔÇÖs inspired songs, novels ÔÇö a countercurrent of people seeking to understand him, even if they themselves donÔÇÖt know anything about him. What is it about him that fascinates us?

Well, I think hes a reflection. Hes this ordinary American, you know? Just this kid from a suburb, whose parents seem like just any other American parents. He fits a certain stereotype of America. Hes white, and I think probably that had something to do with it. As the CIA guy points out, there was another American there  but he was Saudi American, so people were like, Oh, well, its different. [Yaser Esam Hamdi was also captured at the same battle, then detained at Guantanamo and on the U.S. mainland, without trial or representation, eventually leading to a pivotal Supreme Court decision, which ultimately led to his 2004 release and deportation to Saudi Arabia.]

The American medic who first saw Lindh, his first thought was, Is this a CIA undercover guy? Im sure that Al Qaeda thought the same thing. Im not sure they entirely trusted him  trying to figure out the truth of who he is and what he really thought, I think its actually what he says in the interview: He was on this journey and got caught up. He believed in it. Its incredibly frustrating, because people want to put their own sort of ideas of who he should be onto him. But I think all of us were idiots when we were 20 years old.

I know the guys who created Homeland. Lindh was one of the inspirations for them, too. He actually had a big impact on the culture. That was so astounding, going back into the news archives ÔÇö just the amount of coverage of this one guy. It seemed kind of ridiculous. But he came to represent something much, much more. ItÔÇÖs interesting to unpack it. It feels like a different era, doesnÔÇÖt it?

If you could talk to him, what would you ask him?

About these events we filmed, I would ask him about why he didnÔÇÖt say that he was an American when he was questioned, very badly, by those CIA operatives, who, with all due respect, were not very experienced and were not following the right procedures. [Lindh initially claimed to be Irish when interrogated by the CIA.] Again, why didnÔÇÖt he say something there? Because he could have gotten out. He could have said, ÔÇ£Can we talk somewhere else?ÔÇØ He never has answered that question clearly, even when the FBI asked him. Maybe he was traumatized. Maybe itÔÇÖs as simple as that. Maybe he didnÔÇÖt know who these guys were or whether to trust them. I donÔÇÖt know. IÔÇÖd ask him about that. IÔÇÖd ask him how his views have changed over time. A lot of people now will say, ÔÇ£Oh, heÔÇÖs a terrorist. HeÔÇÖs a radical. He supported ISIS while he was in prison.ÔÇØ I donÔÇÖt know. IÔÇÖd be very curious to know how his views have changed, now that heÔÇÖs a grown man.

When you say people said he supported ISIS, you mean just people who didnÔÇÖt know him speculating, or people who knew him?

There was a leaked report from the government, a year before his release, that said that he had some communications that indicated he supported ISIS. Clearly it was a leaked document, and IÔÇÖve never been able to get any more information about it.

You have been making films throughout this whole post-9/11 period ÔÇö about the wars, about the search for bin Laden, about the Arab Spring. YouÔÇÖve spent a lot of time in these regions and with this broader story. How has your idea of your role as a filmmaker changed over this period?

When 9/11 happened, I really thought of myself more as a journalist ÔÇö I was working for Frontline. I do feel like journalism has largely failed us in the last 20 years ÔÇö not completely, but a lot of it has. I feel like storytelling ÔÇö whether itÔÇÖs long-form like documentary, or narrative, or novels ÔÇö is the way to understand how weÔÇÖve changed over the last 20 years. IÔÇÖm drawn toward stories that make us try to understand and hang on to empathy, which is part of our souls but is also easily pushed aside. I think thatÔÇÖs one of the sad by-products of 9/11 and the way in which weÔÇÖve cast and come to understand the other.

What is it about journalism that failed us?

I think journalism, in the midst of crisis, particularly national security crises, is always challenged. When youÔÇÖre covering a war, itÔÇÖs easy to get caught up in that. It is seductive. It is weirdly fun. You can also get sucked into the access dilemma, which is why the beginning of the war in Iraq was covered the way it was. Everyone bought into this collective mind-set. That, coupled with the economic changes in the news media, which weÔÇÖre all familiar with, and how cable news has just fed off of conflict and division ÔÇö not just Fox but all of it ÔÇö as a way of getting ratings. The story itself, it easily led to a new focal point: the enemy, the terrorist that we are going to somehow vanquish. People bought into that. A lot of journalists were writing about that.

Those emotions only take you so far. TheyÔÇÖre not ultimately that interesting. We have to look for other emotions that come into play, whatever it may be. Like The Hurt Locker, which I think was a great example of how we understood a soldierÔÇÖs experience in these never-ending wars. ThereÔÇÖs lots of other examples. Conflict has to be driven by emotions that are complex, otherwise itÔÇÖs not interesting. ThatÔÇÖs very hard to convey in journalism.

I was doing this project once for HBO, before Lindh, about the FBI and homegrown terrorism. I remember having this long conversation with Wolf BlitzerÔÇÖs producer. I really wanted to do something about this, and they could never find the time ÔÇö not just to cover the film, but the whole issue. Could never find the time! How can you never find the time, when you have an hour-plus every night? ItÔÇÖs because theyÔÇÖre just driven by whatever the narrative is that day.

You noted that with the Lindh story, you powered through despite nobody wanting to speak to you. Are there subjects youÔÇÖve tried to tackle over the years but you just couldnÔÇÖt?

Well, I think we still donÔÇÖt know the full story of the CIA torture program. We donÔÇÖt know the full story of the hunt for bin Laden. IÔÇÖve also long been fascinated by the decision to go to war in Iraq, this obsession with Saddam Hussein, and SaddamÔÇÖs double games he was playing with the wider world and internally, not having the weapons [of mass destruction] but acting like he did. Ultimately, thatÔÇÖs what cost him his regime. That story is Shakespearean and will be told at some point, properly.

I think the real challenge is to understand how we have been changed, not necessarily how John Walker Lindh, some kid from Marin County, goes and ends up with the Taliban, but how do we react to that, how do those reactions at the time still affect us today?

I remember several years ago, when ISIS was really commanding the news, you couldnÔÇÖt get past these stories of people from the U.K. and elsewhere, traveling and joining in with ISIS. Back in 2001, John Walker Lindh seemed unique: ÔÇ£What the hell was this guy thinking?ÔÇØ Now weÔÇÖre like, ÔÇ£Oh, this is a thing now.ÔÇØ┬á

But most of the ones that we heard about in the U.S. were FBI plants or setups, by far. The organization that planned the most attacks in the United States was the FBI. ThatÔÇÖs not to say there werenÔÇÖt some crazy people who wanted to go off and join. But they took vulnerable people. John Walker Lindh, had all that happened after 9/11, they would have been on him from the get-go, and would have arrested him before he ever got on the plane. ItÔÇÖs weird to think that he was on the winning side, after all that. The Taliban are back in power. ItÔÇÖs mind-blowing. In the long run, his side won.

Detainee 001 premieres on Showtime on Friday, September 10 at 9 p.m. ET.