Kevin Thompson is a former architect who has been building sets for New York movies for more than 25 years. “Most movies don’t want to be a postcard New York City,” he says. “You want to feel the milieu of the city or a specific neighborhood.” Here, Thompson’s five rules for building a non-cookie-cutter New York set.

1.

Start by looking.

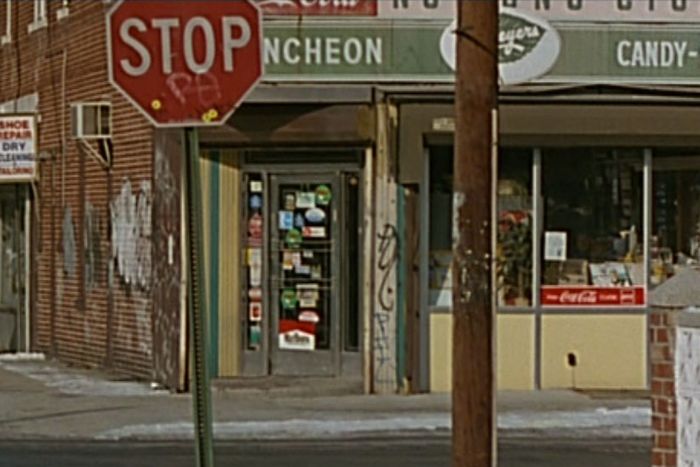

Scouting helps you define the look of the movie, and it happens early on. In the mid-’90s, I did Kids, which was supposed to look like a documentary — gritty and naturalistic — then Party Girl, with Parker Posey, which was supposed to be a stylized, romantic New York for a young person, then James Gray’s first movie, Little Odessa, which was set in Brighton Beach. It’s a Russian neighborhood, and it’s wintertime, sparse, dark. It was important to be in the neighborhood and scout there, to represent the full range of feelings that you have living in that specific pocket of New York. When we went to Brighton Beach, we were taken by how the commercial strip is just one block off the boardwalk and one block off the Atlantic and the beach. This commercial strip, and the elevated train that ran over the street, was so interior and claustrophobic — a striking contrast with the open sky and water a block away. So it felt like an immigrant community that came and didn’t go very far; they settled into this area and made their life, but their life was being strangled in a way.

For the main apartment of Maximilian Schell and Vanessa Redgrave in Little Odessa, we wanted it to feel authentically Brighton Beach and to have the history of the family, because the grandmother lived there, the parents lived there — it was multi-generational. We dressed that apartment from scratch, and what I like to do is reference the things from the actual location. When we’re scouting, we go into these real apartments layered with family history, and I photograph things that seem extraordinary to me. We’ll find utilitarian items, decorative items, random items — this generational history that leads to a certain clutter that doesn’t get thrown away.

2.

Feeling comes first.

Michael Clayton could have happened in Chicago or anywhere, but it was definitely a New York–looking movie with that area of midtown: that corridor of buildings on Sixth Avenue around Radio City. It just has a feeling that reads like New York.

Often it’s necessary to re-create interiors, but you don’t want it to feel like a built set. You want it to feel integral to the film and to the city. For Jonathan Glazer’s film Birth, we built Lauren Bacall’s lobby and apartment, and we wanted it to feel airless, which became a metaphor for the feeling in the film. So you’d go through the building’s front door and through this lobby that’s almost like a mausoleum. And then you go into a small elevator and get up to the narrow hallway. Then you go into the apartment, and there are big windows, but they’re layered with window treatments. So it was as though the people who lived there didn’t want to see out and probably never opened the windows to let air in.

3.

And the set might have to move.

For Birdman, it was necessary to build the entire backstage — the basement, corridors, dressing rooms — because we wanted the set to change configuration as we were shooting. The corridors would shrink and the ceilings would come down as the film became more psychologically intense for Michael Keaton’s character. But we needed to consider the fact that the camera was not going to be cutting around things; it was continuous shots. So a section of the wall would be hollowed out to make it possible for the camera to lead the actors down the corridor and then spin around and be behind them. We’d have people literally taking the wall out and putting it back so that the camera wouldn’t see it. We did a lot of old-fashioned theatrical tricks.

4.

Add some wheels.

I love public transportation, and I love showing it in movies. In many movies I’ve worked on — Little Odessa, Sharper — the trains thread themselves through the city like the circulation system of a body. For The Girl on the Train, we built a Metro-North train car. We studied the patina of these actual train cars, and the age of the metals, and the age of the seats, and the lighting, and the scratches on the glass. But for our train car, we had to be able to take it apart to shoot certain scenes, so we had to custom make a lot of the details. I remember building the big, thick gaskets out of wood and painting them to look like rubber.

5.

Let the city happen to you.

Let the city happen to you. We filmed Little Odessa during a really harsh winter. We were always getting rid of snow, putting it back for continuity. One morning, it snowed so much, and we couldn’t shut down or change the schedule, so instead of having a snow day, everyone had to take the train to Brighton Beach. It was like, “Just get there as soon as you can.” We all showed up exactly four hours late, and everyone was trudging through the snow from the station, and everyone was in the best mood, and we had the greatest shooting day ever. I think now about how on bigger productions, something like that would never happen. It was the spirit of guerrilla filmmaking.

More Reasons to Love New York

- 60 Stars, 50 Seasons, 5 Panels

- 39 Reasons to Love New York Right Now

- Saturday Night Live Is How We Talk With America