Not sure if you’ve heard but Shakespeare is back, babies! At least at the Academy Awards. With three nominations for Joel Coen’s stylish adaptation of The Tragedy of Macbeth and seven nods for Steven Spielberg’s remake of the musical that remade Romeo and Juliet (that’d be West Side Story), the Bard is back in Oscar’s good graces, having finally cracked the top category, Best Picture, for the first time in 50 years. Which seems crazy! Shakespeare has never gone out of style, yet we’re coming off a lean few decades for Shakespeare on film.

In the early years of the Academy Awards, Best Picture nominations for Shakespeare adaptations were incredibly common. But until Spielberg’s West Side Story, no adaptation had made the cut in half a century. Even in Shakespeare’s most reliable Oscar category — Best Costume Design, of course — more than a decade had passed since the last nomination.

So now, with Denzel Washington (in the running for Best Actor) and Steven Spielberg (Best Director, Best Picture) leading the charge back onto the stage, let’s take a look back at the ups and downs of Shakespeare’s relationship with the Oscars through the years: the nominees, the sideways adaptations, the sheer Olivier of it all!

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935)

It wasn’t until the 8th Academy Awards that Shakespeare found glory at the Oscars, with Warner Bros.’ version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, originally a Hollywood Bowl live production also directed by Max Reinhart. The film starred James Cagney as Bottom and Mickey Rooney as Puck, and also featured the screen debut of Olivia de Havilland. Despite commercial disappointment, the film got four Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, where it lost to Mutiny on the Bounty. The film would win two Oscars: Best Editing and, in a write-in campaign, Hal Mohr for Best Cinematography.

Romeo and Juliet (1936)

The success of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, plus some good, old-fashioned toxic masculinity helped to bring about the next Shakespeare Oscar success. Not to be outdone by Jack Warner’s Best Picture nod the year before, Louis B. Mayer changed his previously resistant tune when it came to Shakespeare adaptations and gave in to producer Irving G. Thalberg’s desire to produce a version of Romeo and Juliet starring his wife, Norma Shearer. The film was directed by the great George Cukor, helming his third Best Picture nominee in four years, and while the picture boasted a glitzy cast — Shearer as Juliet, Leslie Howard as Romeo, and Basil Rathbone as Tybalt, which earned him a Best Supporting Actor nod — the critics came after the film for the advanced ages of actors meant to be portraying teenagers, in particular a fiftysomething John Barrymore as Mercutio. Tragically, Thalberg died on the night of the film’s Los Angeles premiere, preventing him from seeing his name attached to not only Romeo and Juliet’s Best Picture nomination, but also the one for The Good Earth that followed the very next year. Both Thalberg and Shearer would lose out in 1936 to The Great Ziegfeld, which took Best Picture and Best Actress for Luise Rainer.

Henry V (1946)

And so begins the great Oscar marriage of William Shakespeare and Laurence Olivier. Henry V is the first of four Olivier-starring Shakespeare adaptations to see Oscar nominations, three of which he directed himself. His name became synonymous with Shakespeare on the big screen for the better part of two decades — unrivaled in that regard, really, until Kenneth Branagh came along in the late ‘80s. Originally produced as a morale booster for the Allies during World War II, the filmed version of Shakespeare’s play about the Battle of Agincourt was released in Britain in 1944 before making it to the States in 1946. Filmed in three-strip Technicolor, the film was hailed for its dazzling visuals, and unlike the previous two Shakespeare adaptations to earn Best Picture nominations, Henry V was a legitimate critical and popular hit. Nominated for four Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Color Art Direction, and Best Dramatic Score, it would win an Honorary Oscar for Olivier for “outstanding achievement as actor, producer and director in bringing Henry V to the screen.”

Hamlet (1948)

Olivier’s greatest Oscar triumph came with his adaptation of Hamlet, which earned him not only the Academy Award for Best Actor, but was also named the Best Picture of 1948. It was the first time that a film made outside the Hollywood studio system won Best Picture. Praised equally for his performance and direction, Olivier’s Hamlet was also the bane of purists who were aghast at the cuts he made (no Fortinbras! no Rosencranz! no Guildenstern!) to deliver a two-hour Hamlet. In addition to the two major awards it won, Hamlet also took home Oscars for Art Direction and Costume Design, kicking off a longstanding love affair between those two categories and adaptations of Shakespeare.

Julius Caesar (1953)

Taking a break from his marriage to Olivier, Oscar enjoyed a brief dalliance with Marlon Brando (who wouldn’t?!) and tossed five nominations to this Shakespeare adaptation from producer John Houseman and director Joseph L. Mankiewicz. It featured an all-star cast including Brando as Mark Antony, James Mason as Brutus, John Gielgud as Cassius, Greer Garson as Calpurnia, and Deborah Kerr as Portia. Brando was at this point still most famous for A Streetcar Named Desire, and there was a high degree of skepticism at the time that his preferred method of mumbly line delivery would be a disaster amid the diction demands of Shakespeare. Those concerns proved to be unfounded, if the critical response was any indication. He received his third Best Actor nomination for this performance, and while he lost out to William Holden for Stalag 17, he’d triumph the next year for On the Waterfront.

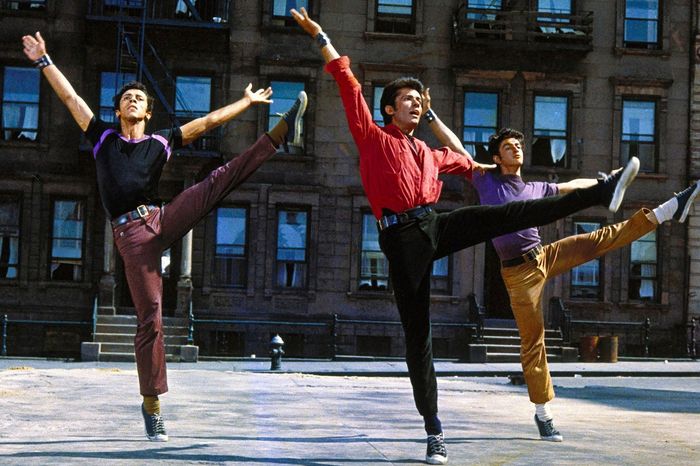

West Side Story (1961)

The great re-imagining of Romeo and Juliet set in the rough-and-tumble streets of New York City has been revisited plenty this year. But in terms of Oscar, its ten wins — including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (George Chakiris) and Best Supporting Actress (Rita Moreno) — placed it second at the time to Ben-Hur for most ever. And while Shakespeare is never more than deeply in the background when it comes to evaluating this film, it does technically stand as the most awarded Shakespeare adaptation of all time.

Othello (1965)

After Olivier’s production of Richard III earned only a Best Actor nod for its writer/director (he lost to Yul Brynner for The King and I), he was back in 1965 in Othello, in what was essentially a filmed version of the National Theater Company’s staging of the play. Oliver was nominated in Best Actor, along with the film’s other principals Frank Finlay (as Iago), Maggie Smith (as Desdemona), and Joyce Redman (as Emilia), though the entire endeavor is quite understandably overshadowed these days for Olivier’s decision to play Othello in blackface.

The Taming of the Shrew (1967)

Italian director Franco Zeffirelli was originally going to cast Sophia Loren and Marcelo Mastroianni as Kate and Petruchio, but the roles eventually went to Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, who financed much of the production themselves. This was the fifth movie that Taylor and Burton had made together in their still fairly young marriage, released just a year after Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. The Oscar halo of that film failed to extend to Taylor and Burton, however, and despite BAFTA nominations for them both, they were shut out of the Oscar nominations, with the film ultimately only receiving nominations in Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design.

Romeo and Juliet (1968)

Zeffirelli’s second go at charming Oscar with the Bard’s poetry the very next year was far more successful, with his acclaimed version of Romeo and Juliet. Praised by critics at the time for his decision to actually cast young actors in the title roles, Zeffirelli’s film stars Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey as Romeo and Juliet, though Zeffirelli’s casting search at the time leaves us with quite a few tantalizing what-if scenarios. To think there is some corner of the multiverse out there where Paul McCartney and Anjelica Huston played Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers. The film was nominated for Best Picture and Zeffirelli for Best Director — both lost to Oliver! — and it won Oscars for costumes and cinematography. This is the last time that a straight-up Shakespeare adaptation was nominated for Best Picture and, until West Side Story this year, the last Shakespeare adaptation of any kind to be recognized in the top category.

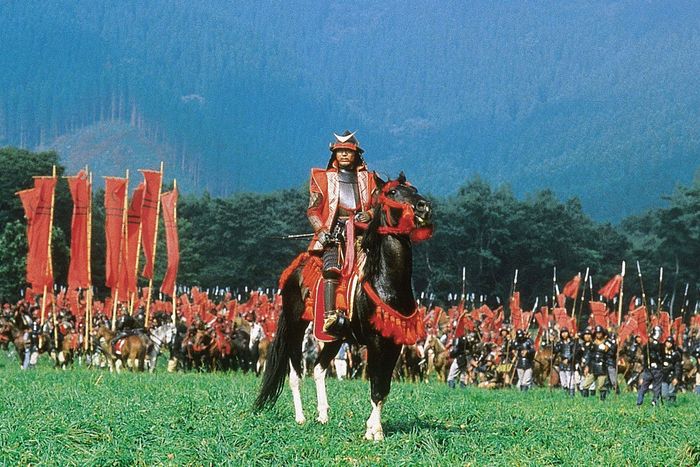

Ran (1985)

Shakespeare was absent from the Oscars for the entire 1970s, then crept back into the fold in 1985, albeit in a most unexpected way. Akira Kurosawa adapted King Lear into a 2 hour and 40 minute epic that earned the legendary director the only Oscar nomination of his career (in Best Director). Also nominated for its Cinematography and Art Direction, the film won the Oscar for Best Costume Design for Emi Wada, who would go on to design costumes for Zhang Yimou films like Hero and House of Flying Daggers.

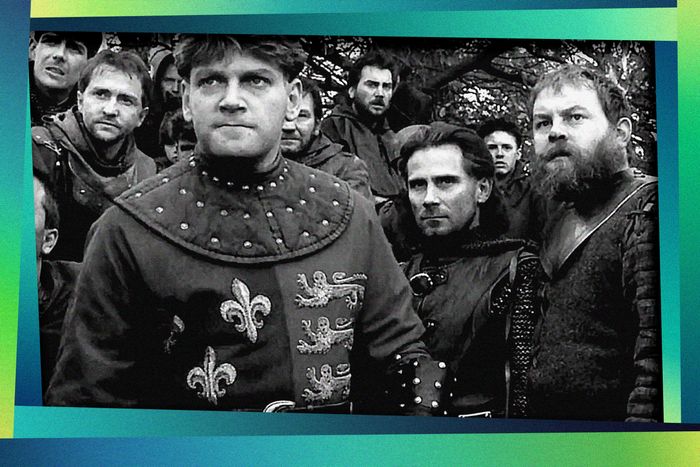

Henry V (1989)

The mantle of cinema’s signature Shakespeare adapter passed in the late ‘80s from Olivier to another writer/director/star, Kenneth Branagh. With this, his directorial debut, 27-year-old Branagh became a critical sensation, becoming the first man to earn simultaneous Best Director and Best Actor nominations since Warren Beatty for 1981’s Reds. The film was praised, among other things, for its brutal staging of the Battle of Agincourt, for Patrick Doyle’s score (not nominated, sadly), and for Phyllis Dalton’s costumes, which won the film’s only Oscar.

Hamlet (1990)

Franco Zeffirelli back again! His 1986 film Otello, based on the Verdi opera which was in turn based on Shakespeare’s Othello, garnered the obligatory Costume Design nod and nothing more. But surely his Hamlet would bring home the goods. It had Mel Gibson in the title role! Glenn Close as Queen Gertrude! An absolute murderer’s row of British talent in the supporting roles, including Alan Bates, Paul Scofield, Ian Holm, Stephen Dillane, Pete Postlethwaite, and a young Helena Bonham Carter as Ophelia! A score by Ennio Morricone! Still, the critics weren’t all that moved (see: Mel Gibson as Hamlet), and in the end the film got Art Direction and Costume Design nominations and nothing more.

Richard III (1995)

Unfortunately for several reasons, director Richard Loncraine’s version of Richard III didn’t catch on with the Oscars outside of a pair of nominations for (say it with me!) Art Direction and Costume Design. We were yet a few years away from Ian McKellen being welcomed into the Oscars fold. It’s too bad, because his performance as the title character is villainous bliss, and the film’s updating of the setting to a 1930s Britain vulnerable to creeping fascism is fascinating. McKellen was nominated for the Golden Globe and the BAFTA but was snubbed on Oscar nomination morning in favor of a surprise nod for the late Massimo Troisi for Il Postino.

William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet (1996)

Alas, the squaresville Academy was not nearly cool enough to get onboard with Baz Luhrmann’s color-blasting, pop-infused, DiCaprio-and-Danes telling of the star-crossed lovers beyond a solitary nod for Art Direction. We do bite our thumb at thee, Oscar voters of 1996!

Hamlet (1996)

After previous adaptations of Hamlet by Olivier and Zeffirelli cut significant portions of Shakepeare’s original work, Kenneth Branagh said “fuck that” and abridged absolutely nothing, using the full text of the play for his four-hour-and-two-minute version, starring (of course) himself as the Prince of Denmark. As if challenged by the star power of the Mel Gibson/Glenn Close version, Branagh went ham, casting Julie Christie as Gertrude, Kate Winslet as Ophelia, Derek Jacobi as Claudius, and populating small roles with the likes of Robin Williams, Billy Crystal, Jack Lemmon, Charlton Heston, John Gielgud, and Judi Dench. Despite the glorious big-ness of it all, Oscar didn’t bite when it came to Best Picture/Director/Actor, nominating it instead in [bell chimes] Art Direction, Costume Design, and Dramatic Score, in addition to a rather hilarious nomination in Best Adapted Screenplay for a screenplay Branagh famously declined to adapt at all.

Titus (1999) and The Tempest (2010)

Hamlet kind of burned out the Academy’s taste for Shakespeare, it seemed, and while Branagh directed two subsequent Shakespeare adaptations — Love’s Labour’s Lost in 2000 and As You Like It in 2006 — the Academy ignored them. And so the mantle of Hollywood’s great Shakespeare steward remains vacant for the moment. The closest anyone’s come to making a stab for it in the last 30 years has been Julie Taymor, the acclaimed/notorious film and theater director (Across the Universe; Broadway’s The Lion King and Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark). Her two big-screen Shakespeare adaptations were certainly visual spectacles. Titus, adapted from Titus Andronicus, was an over-the-top bloody affair, luxuriating in gore and camp and sexual transgression (you cast Alan Cumming for a reason). The Tempest starred Helen Mirren as “Prospera,” a gender-swapped version of the play’s central sorcerer, and the film was buried in bad reviews for its special effects. In both cases, lone nominations for Best Costume Design were all that came of what could have been known as the Julie Taymor Era of Shakespeare on film. What might have been.

The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021) and West Side Story (2021)

And here we stand: 53 years since Romeo and Juliet’s Best Picture nomination, 32 years since Henry V’s Actor/Director nominations, and 11 years since the last nomination of any kind, Joel Coen and Steven Spielberg have returned the Bard, in various guises, to Oscar’s embrace. West Side Story is its own thing, so caught up in the legacies of Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim that bringing Shakespeare into the discussion feels superfluous. The Tragedy of Macbeth, however, is more interesting in terms of whether its success might herald a new wave of Shakespeare adaptations. Like Olivier and Branagh and even Taymor before him, Coen and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel brought a striking and intentional visual design to the play. Denzel Washington — who’d starred alongside Branagh in the latter’s sadly not-nominated 1993 Much Ado About Nothing — feels like exactly the right actor to revive Shakespeare’s presence in the acting categories. Maybe this is the dawn of the next great Oscar era for Shakespeare. Until then, we’ll wait and see what tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow bring.