Everything that’s great, and everything that’s stiff, about Black-ish is present at the start. In the pilot, California marketing executive Dre Johnson gets promoted to senior vice-president of the Los Angeles ad firm Stevens and Lido. It ought to be one of the greatest days of his life, but he can’t shake the feeling that he’s paying an unforeseen price for living the dream. Dre was raised in Compton, but his children are Sherman Oaks blue bloods.

He takes it personally when they come off bougie and detached from any real sense of struggle. His eldest son, Junior, prefers field hockey to basketball and goes by “Andy” at school; his youngest son, Jack, is unaware that Barack Obama is America’s first Black president. So when Junior comes home asking if he can have a bar mitzvah, his father calls a family meeting, barking, “I may have to be ‘urban’ at work, but I’m still going to need my family to be Black. Not Black-ish, but Black.” It’s the textbook Dre speech — the first of many — establishing a hard-line on race and place for the other characters to carry toward enlightenment.

When Black-ish debuted in 2014, it was hailed as a “revolutionary” work that spoke to Black anxieties and had the potential to shake white audiences. It made a mint prodding viewers to take inventory of their own closely held misconceptions about Blackness. (Donald Trump called it “racism at the highest level,” complaining that no one would be allowed to make a show called White-ish.) It was a show about navigating two worlds, about how people of color are asked to self-edit and assimilate in order to move through elite circles, and also about the conflicts among Black boomers, Gen X–ers, and zoomers over self-expression, protest, romance, and identity.

Series creator Kenya Barris grew up loving The Cosby Show and made his mark on television in the aughts as a writer for the UPN sitcom Girlfriends and a developer for the same network’s America’s Next Top Model. He brings an appreciation of sitcom history to the affair. As much as the plight of the Johnsons resembles that of the Huxtables, the conversations they have around the house seem patterned after the divisive Norman Lear shows. The kids push back against Dre the way Gloria and Michael nudge Archie Bunker on All in the Family. Their family debates helped the show achieve an intergenerational bird’s-eye perspective on the topic of the week.

But it also treated hearing both sides of the issue as a virtue, an end in itself, even as it implicitly endorsed its patriarch’s point of view. Now that it’s over, it’s worth reconsidering how it handled the complexities of Black thought in rapidly changing times. Over eight seasons and three presidencies, Black-ish fostered vital conversations, but you wonder how much of its success can be attributed to its concessions and how much feistier the series could’ve been were it only a little less defensive of Dre’s, or Barris’s, perspective. How uncomfortable did it allow its viewers, or its characters, to ever really get?

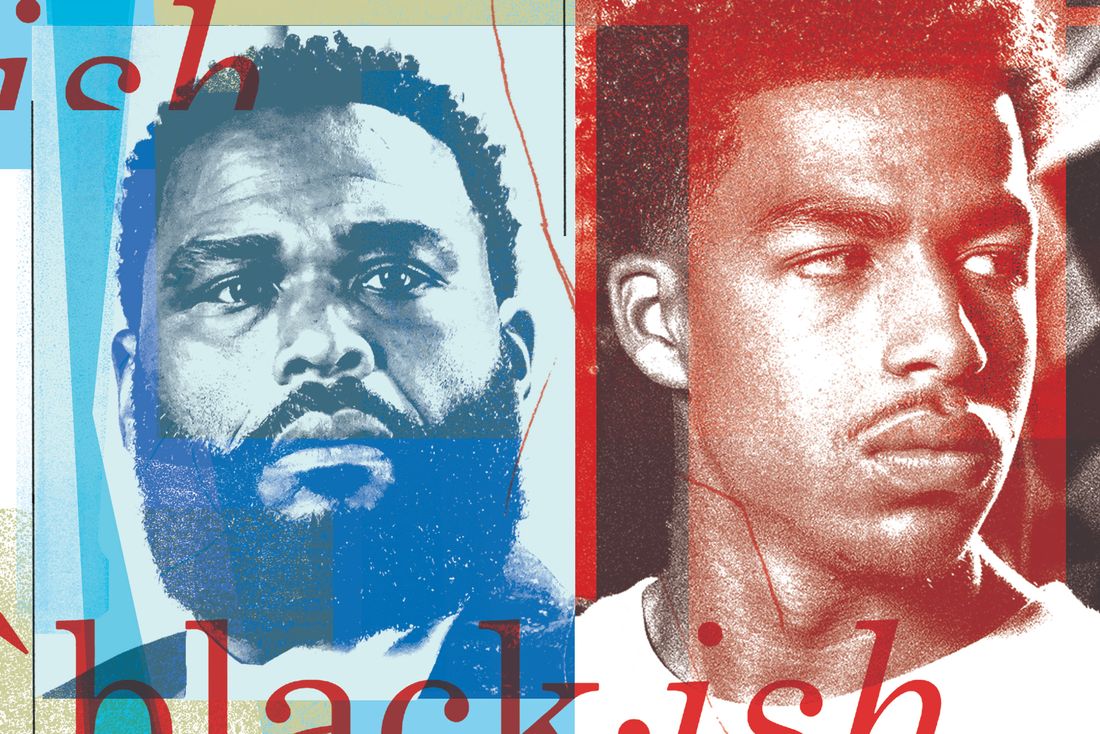

Dre Johnson (Anthony Anderson) in the series debut, basking in his praise and posturing.

Three generations of Johnsons, including Dre’s parents, Pops (Lawrence Fishburne) and Ruby (Jenifer Lewis), gather for a tense family town hall on police brutality. Such provocative scenes put Black entertainment icons in direct conversation onscreen with the next generation of Black Hollywood: Marcus Scribner, Yara Shahidi, Marsai Martin, and Miles Brown.

The Johnsons go to the twins’ school play about Columbus Day, and Dre is dismayed by the historically inaccurate way that the holiday is portrayed.

ABC said it shelved the episode over “creative differences” with Barris; it was put on Hulu in 2020. “We were one year post-election and coming to the end of a year that left us … grappling with the state of our country and anxious about its future,” Barris said upon the episode’s release. “Those feelings poured onto the page, becoming 22 minutes of television that I was, and still am, incredibly proud of.”

Dre Johnson (Anthony Anderson) in the series debut, basking in his praise and posturing.

Three generations of Johnsons, including Dre’s parents, Pops (Lawrence Fishburne) and Ruby (Jenifer Lewis), gather for a tense family town hall on police brutality. Such provocative scenes put Black entertainment icons in direct conversation onscreen with the next generation of Black Hollywood: Marcus Scribner, Yara Shahidi, Marsai Martin, and Miles Brown.

The Johnsons go to the twins’ school play about Columbus Day, and Dre is dismayed by the historically inaccurate way that the holiday is portrayed.

ABC said it shelved the episode over “creative differences” with Barris; it was put on Hulu in 2020. “We were one year post-election and coming to the end of a year that left us … grappling with the state of our country and anxious about its future,” Barris said upon the episode’s release. “Those feelings poured onto the page, becoming 22 minutes of television that I was, and still am, incredibly proud of.”

In many ways, Dre is a stand-in for Barris. Raised in Los Angeles in Inglewood and Pacoima, Barris saw the trajectory of his life change drastically after his father lost a lung in an accident and won a settlement that lifted the family into a new tax bracket. Black-ish pulled from that and from Barris’s life as a parent of six with his wife, Dr. Rania “Rainbow” Edwards-Barris, an anesthesiologist whose biracial background is mirrored in the journey of doctor-mom Rainbow “Bow” Johnson. The show’s outlook seems to have been informed by the trajectory of the Black television writer excelling in Hollywood. It is success oriented and deeply attentive to optics. Dre and Bow are getting to the money, and they think they represent us all, so they must move carefully. It’s the same “Talented Tenth” mentality Ye pushed in the years he was clamoring for acceptance in fashion and demanding the respect enjoyed by guys like Steve Jobs and Walt Disney. (The first sound you hear in the Black-ish pilot is the Army chant that opens “Jesus Walks.”) But rarely were Dre and Bow checked in their belief that Black capitalism can save everyone.

In the series opener, Dre says he’s an inspiration to his Black co-workers: “There were so few of us at Stevens and Lido that being Black made it feel like you were part of a little family. So when one of us made it, it was kind of like we all did. And right now, I was that one.” How the family he daps up on the way to the office might feel about the firm having space for only the one isn’t mentioned. In season seven, when Bow becomes a partner at the hospital, she abruptly realizes the young Black women coming up in the field view her as a supervisor and not a friend. The final-season premiere sees her hanging out with Michelle Obama, after which Bow yearns for a peer group she can never have and laments how lonely it is at the top after all these years. Dre tells her it is thanks to her work that those women even have a cohort in their profession. It’s not untrue; it’s just that this is the same line we hear whenever Black celebrities get in trouble and marshal their fandom against their critics by portraying themselves as civil-rights pioneers (another page from the Ye playbook). Bow’s takeaway is that she can’t sit with the younger doctors but can sit in the pride of having paved the way for them. It’s a peculiar response to the conflict: Bow embarrassed herself when she took the women out for drinks, then left in an elitist huff when they read hospital higher-ups for what they are. Black-ish offers her a pat on the back for being a boss instead of wrestling with how she might not be the best one and why that is, just as it often coddled its leads through their mistakes and short-sightings.

You can see Black-ish negotiating how confrontational it wants to be as early on as “The Dozens,” a season-one episode that traces Black humor through history, carefully avoiding unsettling imagery, as a card from producers that says “Slavery Animation Too Much of a Bummer” stands in for a scene that might have depicted what happened to the African abductees on the Middle Passage. The show felt more comfortable going there in its front half. It set musical numbers on plantations in the exquisite, informative season-four opener “Juneteenth.” But the approach shifted as the tone of the national discourse soured around the Trump election. Suddenly, Black-ish had a valuable platform in a moment of great racial tension. What passed as edgy before the mayhem of 2016 rapidly felt tepid. Black-ish tried to mind the changes, but its flair for cozy resolutions softened its word. Season three’s “Lemons” met the Trump presidency head-on, but its assessment feels late and pat now. “Instead of letting this destroy us,” Dre suggests in a speech at the end of the episode, “we take the feeling you guys felt the day after the election and say that morning we all woke up knowing what it felt like to be Black.” It was wild to tell white people that not getting one thing they want is akin to Blackness. The feel-good message feels less good when you know how many white liberals came down with “ally fatigue” in the Trump years.

Black-ish put its thesis plainly in season two’s “Hope,” where a family chat about police brutality gets hopeless and the only thing they can agree on is the merit of talking through the issues. It was cathartic but ultimately quaint, a much tamer reading of the matter than, say, that of The Carmichael Show, whose “President Trump” episode had higher stakes and no easy solutions. The point of the protest movements of 2014 and 2020 wasn’t “Hey, let’s get everyone talking.” It was that solutions are multifaceted. Cultural sensitivity was important; so was making people uneasy.

Dre and Junior butt heads over the most effective way to protest in the age of social media. Dre resorts to a double burn, calling his son a “Black square.”

Bow (Tracee Ellis Ross) meets a powerful new friend (Michelle Obama, as herself) and realizes it’s lonely at the top.

Dre and Junior (Scribner) heal new and old wounds in the penultimate episode where they go on a “man trip” with Pops.

The Johnsons, and especially Dre, say good-bye to the life they thought they had figured out in the series finale.

Dre and Junior butt heads over the most effective way to protest in the age of social media. Dre resorts to a double burn, calling his son a “Black square.”

Bow (Tracee Ellis Ross) meets a powerful new friend (Michelle Obama, as herself) and realizes it’s lonely at the top.

Dre and Junior (Scribner) heal new and old wounds in the penultimate episode where they go on a “man trip” with Pops.

The Johnsons, and especially Dre, say good-bye to the life they thought they had figured out in the series finale.

The series’ most uncomfortable moments stem from the characters’ burning desire to be respected, seen as pioneers in their industries. Dre is afraid of selling out but is also an overachiever who craves business accolades and the approval of his co-workers, even if it means fielding their kooky misconceptions about Black people and saving their asses in questionable campaigns. (In season one’s “Switch Hitting,” Dre tries to woo an ad exec played by Michael Rapaport by inviting the guy over for a disastrous dinner, one only arranged to prove his authentic Blackness to a white man who says shit like “Kunta Kinte was thuggish ruggish for real.”) White validation is important to Dre, even if he resents always being called on to provide a diluted Black perspective. He makes even that into a self-competition. “White people trust me to tell them about Black people and what they want,” he boasts in season three’s “Richard Youngsta,” one of Black-ish’s worst episodes. Chris Brown plays the titular rapper, who stars in a liquor ad Dre is tapped to craft. No one in the office takes issue with a scene where one sip transforms a frowning Black woman into a flirty white one. We later watch Dre defend Stepin Fetchit when his wife and mother accuse him of profiting off harmful stereotypes, much like how the actor made millions portraying lazy Black characters in the 1930s: “Without Lincoln Perry paving the way, we might not have a Denzel.” All this splitting hairs about the gains made in spite of minstrelsy feels ginned up, an excuse for the episode to unpack its own historical implications unchallenged.

Black-ish often set up unrealistic scenarios deliberately in service of arriving at a teachable moment. It’s classic sitcom to occasionally put your characters through the ringer, but Black-ish sometimes got there by feeding one of them a hot take that contradicted their history. Bow shows deference to law enforcement in “Hope,” but “Becoming Bow” revealed she grew up on a commune raided by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms in the mid-’80s; you’d think she might harbor resentment. “Hope” needed someone on the other side of the argument, as so many pivotal moments in the show did. Season one’s “Elephant in the Room” asked us to believe Junior would join the Young Republicans at school all so the Johnson family can have a discourse on the relationship between Black voters and the Democratic Party, at the cost of making Junior look like a dupe. Talking through the issue at work, Dre calls his kid an “Uncle Tom.” It’s an unfathomable play even for a man prone to faking heart attacks when he doesn’t get his way, à la Redd Foxx in Sanford and Son. In both cases, the show went out of its way to hit the counterarguments — “Cops do have a place in society”; “Black voters’ support of the Democratic Party is blind” — as if it were talking past its Black viewers to white ones who couldn’t relate.

Junior and Dre’s relationship highlights a key area where Black-ish consistently missed its mark. Junior is the namesake, and he turned out nerdy, and he is constantly having his masculinity and Blackness interrogated in ways that rarely feel critical of the characters doing the piling on. The show treated Junior’s love of tabletop role-playing games as a point of embarrassment while a generation of prideful Black nerds was blooming. Megan Thee Stallion is a serious anime fan; Travis Scott reportedly made $20 million off Fortnite. An advertising legend should have been more curious about the appeal of a market he didn’t understand. That he wasn’t is testament to the palpable Gen X–ness of Black-ish and its mastermind. Junior gets under Dre’s skin the most of all the kids. They don’t get along until the end, when the son becomes his father, landing both a job at Stevens and a girlfriend studying to become a doctor. It’s only when Junior loses the girl — a breakup that forces three generations of Johnson men to be vulnerable with each other — that Dre apologizes for spending the entire franchise trying to force Junior to be someone else entirely and failing to appreciate the considerate, emotionally intelligent kid he raised. He seems surprised his kids turned out the way they did, as if their moneyed airs weren’t almost entirely thanks to his needling insistence on enjoying the same signifiers of wealth as affluent white professionals.

When Dre wakes up in the Black-ish pilot suddenly deeply upset about the gap between the interests, ideas, and mannerisms of his children and what he feels is a more traditional Blackness, he’s really sitting in conflict with his own choices. This was always a show about a midlife crisis; the concerns of the children and grandparents orbit Dre’s version of existentialism. And a show about a lovable crank can only change him so without disturbing its core dynamic. With Dre at the heart of Black-ish, so much— too much — time was spent examining his worst impulses. Harder to watch than his behavior in “Richard Youngsta,” Dre outs his sister Rhonda (Raven-Symoné) to their mother in season one, believing he’s helping out; by season six, Dre is still struggling with Rhonda’’s sexuality, telling her she “can’t handle” adopting a child. All of this was realistic. Some families take years to come to grips with a person coming out, or never do. But it is tired having queer characters appear as a means for the straight characters to fumble toward belated understanding, in the same way that it grates having wealth as the elephant in the room for so many of these conversations about race.

Black-ish goes out the way it came in. Dre gets dressed to “Jesus Walks” (again), but something’s different. His 2014 monologue was about exclusion: “I guess for a kid from the hood, I’m living the American Dream. The only problem is whatever American had this dream probably wasn’t from where I’m from.” Now, having won a Super Bowl commercial, he’s happy he found a way to “go from broke to the Oaks without a jump shot, a No. 1 hit, or being Tyler Perry.” Just last episode, Dre told Junior he regretted “thinking that the most important thing was getting the same opportunities as my white counterparts.” He meant business. Dre leaves Stevens and Sherman Oaks behind for a beautiful home in proximity to Black families.

I wish these characters could have a do-over. Imagine if the dinner banter didn’t always revolve around criticizing someone’s Blackness. If the Johnsons really sought out Black friends. What if fewer punches were pulled? What if we left things messy instead of virtuous? What if “Please, Baby, Please,” the season-four stunner in which the Johnsons each speak with unrestrained honesty about their Trump-era fears, wasn’t shelved for two years? What if Black-ish didn’t have any interest in selling us the dream that in our darkest hours, Americans always help each other? We’ve seen too much of the worst of each other now to buy in.