Before the pandemic, Laurence Fishburne was preparing for his Broadway return in American Buffalo, and weeks into lockdown, he was still rehearsing over video calls with his co-star Sam Rockwell. “We continue to work the craft for its own sake,” Fishburne says over the phone, several weeks after we first spoke. “It has kept us all in a good place emotionally because it’s a mourning process — a way we can actually engage with the words and with each other and let go of it at the same time.” Dedication to the craft has been his hallmark since he began as a child actor on One Life to Live, when he revered performers like Marlon Brando and Sidney Poitier. Almost 50 years later, he has built his own body of work, which includes films directed by Spike Lee, John Singleton, Francis Ford Coppola, Abel Ferrara, and Lilly and Lana Wachowski. “It’s not about the starry-eyed shit,” he said. “I’m not comfortable with this word star or movie star. I’m comfortable with being an actor. I’m comfortable with being an artist.”

How does it feel for the Broadway revival of American Buffalo to be delayed?

It’s like we were preparing a great meal and then suddenly we were told we had to close the restaurant, so we’re just like in the kitchen exchanging recipes anyway. Rockwell is somebody I’ve admired for years and always wanted to work with. So now we’re doing that. The FaceTime and Zoom rehearsals are just us going, “Hey, man, I was thinking about a dish like this.” “What do you think you need for it?” We continue to work the craft for its own sake, and that’s been fun and a lifesaver because it has kept us from sliding into a depression. Yeah, there’s no audience; that doesn’t matter sometimes. Sometimes you just do it for the sake of doing it.

Is that paradoxically liberating?

Yes, it is. It’s brought a lot of joy into my life. It gives me something to look forward to.

Shortly after Two Trains Running on Broadway in 1992, you said that just as every good Catholic has to go to church, every good actor has to go to the theater. It seems you revisit it as a pilgrimage point throughout your career.

Absolutely, making the Hajj. When I worked with [theater director] Lloyd Richards back in those days, he said that work gives texture to the other work. Being in the theater, you’re exercising all of your muscles as an actor, and you’re using all of your senses as an actor. You’re not at the mercy of technology. You’re not in the hands of an editor. You’re collaborating with other actors. You’re collaborating with your creative team, director, lighting, sound, stage, all of that. I think the most important thing is you’re in communion with an audience. You’re in communion with a group of human beings. It’s a ritualistic happening. That sense of the community and doing something live for the enjoyment of other human beings is really special.

Two Trains was also when your co-star Roscoe Lee Browne started calling you Laurence instead of Larry.

Yeah, that was the shift. I was Larry as a child. The only people that called me Laurence were my mother and my father, basically. By the time we got to doing Two Trains Running, I was 30. On set, I was always the youngest person, and yet I had children by that time and I had just done Boyz n the Hood. And so I had a shift of consciousness out of being a kid and thinking of myself as a kid and started really thinking of myself as a grown man. I needed to do that because, as actors in general, we have to be childlike in order to do what we do, but we have to live in the real world. And what most people want as adults is to be taken seriously. Larry Fishburne was a kid; Laurence Fishburne is a grown man.

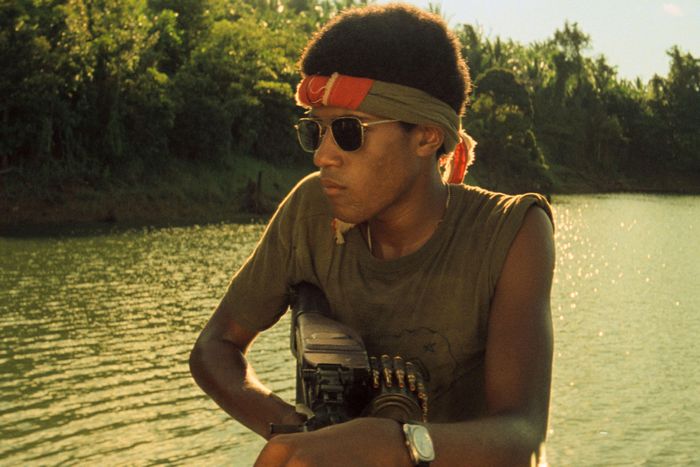

You moved to L.A. after spending almost two years in the Philippines for Apocalypse Now, and I got the sense that returning was a shock. Was that because you felt you were being read as a Black man in a way you hadn’t been used to before?

That’s right. When you grow up in a place like the United States as a person of color, you’re always told that you’re the minority, and that means you always have to be on your guard. Like, it’s never safe for you to relax somewhere because there’s always somebody who’s going to go, “Hey, you’re not supposed to be here.” So I go to the Philippines. I’m 14 years old, and everybody looks like me. Everybody’s brown, yellow, red. They’ve got Asian eyes, and I’m no longer a minority. I looked quite Asian when I was a boy. My grandmother called me “China boy” because of the shape of my eyes and because of my hair. I grew up in Brooklyn, but my grandmother lived in Queens and I spent time in the Ravenswood projects, which is the only place where I have this nickname — this one particular place in the world. So if I ever hear anybody say “China boy,” I know that they know me from the Ravenswood projects and from Queensbridge projects when I was a kid.

Are you part Asian?

I’ve done the DNA thing; it doesn’t appear so. It appears that I am mostly West African, English, Irish, and Scottish. But the West Africans — there was definitely trade between West Africa and China. When you look at somebody like Mandela — he’s Xhosa, but you look at his face and you’re like, Yeah, I wouldn’t be surprised.

In the Philippines, there was nowhere I could go where I wasn’t welcome, where people were going to look at me like I wasn’t supposed to be there. Then I come back to America, and now I’ve got, Oh, this again.

And you were older.

I was 17. When you’re no longer in a minority, suddenly you stand up a little straighter. I don’t have to be on guard anymore, so now I come back and it’s like, Oh, wait … Oh, right, right. Oh, this? [Gestures to himself.] Oh, fuck. Okay. All right. I’ve got this thing that I’ve done, and this thing is the most expensive movie ever made with the greatest living American filmmaker and the actor who changed everything. And these guys are artists. If I’m associated with these guys, then I must have some gifts. I must have some value. Maybe I’m not as valuable as you think I am, but I know inside that I’ve got something to offer and that it’s pretty special. I’m 17, so there was certainly a lack of humility on my part, but at the same time, there is the culture of racism and discrimination that is inherent in American society. I’m not trying to blend in; I’m trying to stand out. I’m trying to say, “Look at me. Check me out. I’m superspecial.” They’re like, “No, motherfucker. If you don’t sit your Black ass down, you will go to jail.”

Was there a specific moment when you understood that?

A couple of really important things happened. One of the most important things that did not happen to me happened to a lot of guys who were friends of mine. So Sean Penn, Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, Charlie Sheen — all those guys that they used to refer to as the Brat Pack — they were all friends of mine. I met them because Emilio and I became best friends in the Philippines.

And you saved his life.

And I saved his life and he saved mine just by virtue of the fact that we were friends because there were no other 15-year-olds around. Having the company of somebody who was my own age and male and from America was also a lifesaver for me. I watched all of my friends, who I was introduced to by Emilio, become stars in their 20s. Now, they had only started acting in their teens; I had started acting when I was 10. I watched them all star in their own movies in their 20s. That didn’t happen for me until I was 30, but it was really important. It was difficult for me to watch because, of course, that immature, selfish part of me was going, What about … ?

At the same time, they’re my friends, so I’ve got to be happy for them, too. I can’t be like, These guys suck, because they don’t. They’re doing their thing, and it’s great what they’re doing. I just don’t get to be included. That was hard. That was about the color of my skin; that wasn’t about my character. But it was good because it humbled me. I think it made me a better human being. I could have chosen just as easily to remain bitter about it. I chose to look for the high road. I came back to New York, and I went back to work in the theater. I did seven years. I did a play called Suspenders here with a guy that directed me at the New Federal Theatre downtown. It was a two-hander, and it was written by one of the guys from the Last Poets. It’s this white guy and this Black guy in an elevator, and the elevator gets stuck. The white guy has gone into this freight elevator to kill himself. He runs into this janitor, me, who helps talk him out of killing himself. That was the first play I had done in about seven years since leaving New York to go do Apocalypse.

When you did King of New York, you’ve said you felt as if you’d gotten out a lot of anger about your career, so I assume it was about this disparity?

Yeah. I was certainly frustrated and angry about the fact that there weren’t as many roles available to people who looked like me as there were available to people who looked like Emilio. So was everybody else who looked like me and who looked like you. That shit wasn’t fun, but it was real. It was our reality, and we had to figure out something to do about it. Just being angry about it wasn’t going to get it, so I had to take the anger and transform the anger into something else. It’s what I spent a long time doing. Between 1980 and 1989, that’s really what I was trying to do — find things I could do that would demonstrate to people my worth and my ability as an artist.

So how did King of New York fit into that?

Well, King of New York was written for an actor named James Russo. Actually, what really happened was I was here in New York. I had been married for about five or six years. My wife at the time had started to dabble in casting movies, and she ran into a cat named Randy Sabusawa, who was one of the producers on King of New York, and he got to talking about this filmmaker, Abel Ferrara, and they were getting ready to do this movie, and they were looking for the baddest motherfuckers in New York. My wife said, “My husband is one of the baddest motherfuckers in New York.” Randy arranged for me to meet Abel, and I met with the two of them. It was for the part that Wesley Snipes wound up playing in King of New York, which was David Caruso’s partner. I had read the script, and I’d seen this part, Jump, and I was like, “Dude, you’ve got to let me play this part.” He was like, “Nah, I got Jimmy Russo. He’s going to do the thing.” I was like, “Okay.” Then I started working with my manager, Helen Sugland, and she was like, “Jimmy Russo is in Canada working on a movie called We’re No Angels with Robert De Niro and Sean Penn. He’s not going to be available because they’re not going to be finished in time.” I went back to Abel and was like, “What about me? What about me?” He was still hoping that Jimmy was going to get away, but it didn’t eventuate. So, I said to him, “Do me a favor. Let me come in. I have an idea for the character. Let me present this to you.” I went and I got some teeth, some glasses, and some gear, and I came in as the guy, and I just proceeded to regale him with stories for three hours in character. He was like, “Oh, shit.” That’s how I wound up getting that part.

Did you wear the bowler or the Kangol?

I had a bowler cap. I had a Cash Money thing. They had those knockoff tracksuits that said “MCM” on them, so I had one of those. It was all black and white, and I had these Cazal glasses, and I had the gold fronts, and I was walking around his studio just being that ignorant guy. It was like some beat boy walked into his loft and was trying to sell him crack. Let’s just put it that way.

What was it like shooting the fight scene with Wesley Snipes?

We shot it in Queens, underneath the 59th Street Bridge, not far from a neighborhood that I kind of grew up in. Wesley and I have known each other forever, and Wesley faced the same challenges that I did as an African American man, and so it was fucking great that we were in a movie together and that we had scenes together, and that we had this real conflict. He’s taunting me: “Come out, stand up, be a man, face me!” All of that. There’s a thing that he has where he’s taunting me with, “I got some chicken here for you.” The chicken thing, it just kind of happened. I mean, he was cracking on me. He was ad-libbing the whole chicken thing, so when I came around and shot him, it just came out, “Where’s my chicken? Where’s my chicken at?” Much of what’s in that movie is ad-libbed.

Your character in Spike Lee’s School Daze ends by telling the entire campus, “Wake up!,” which is still relevant today. What was attractive about the political consciousness of those films you did in the ’80s?

That was attractive to me as a Black person. School Daze was still dealing with apartheid. And my character is correct: Black people are still catching hell all over the world. And here we are in 2020 with COVID-19, and the numbers of people of color who are passing away and dying from this disease are disproportionate.

Why did you turn down the part of Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing?

There are ways in which [Lee] takes creative license with Do the Right Thing that just didn’t feel right to me. If you have a business in the heart of the African American community — but you’re not African American but you’ve been there for generations — then you become a member of the family, which means you’re basically protected from anything that should happen. Because it was loosely based on the events that had happened in Howard Beach, I just felt that if that pizzeria existed in the Black community in Brooklyn, that pizzeria was part of the community, and so even if there was a riot and even if there was racial tension, that it would not have escalated to the point where they’d just burn down the pizza parlor. Why did they burn down the pizza parlor and not the Korean grocery market? It felt a little disingenuous to me.

I mean, listen, a lot of people think the movie is great, and I get it. There are great things about it. It just wasn’t for me. Pulp Fiction wasn’t for me. Quentin wrote that part [Jules Winfield] with me in mind, too, but it wasn’t for me.

Why not?

I just had a problem with the way the heroin use was dealt with. I just felt it was a little cavalier, and it was a little loose. I felt like it made heroin use attractive. For me, it’s not just my character. It’s, What is the whole thing saying?

What is the internal compass that guides you as an actor to say yes or no to a project?

My intuition guides me absolutely.

Do you feel like a work needs to have a moral clarity to it?

I don’t know if it’s that or not. I just know with those particular pieces, it just didn’t feel like it was on the mark for me. I understand why Spike wanted me for Raheem. Raheem is a sacrifice in this movie, and he has the whole love-hate thing, which is really quite poetic and beautiful. I just didn’t feel like I could carry that with everything else that was going on. It didn’t connect up for me. I get it connects for the audience. When the audience sees the movie, it makes sense. When I read it, it just didn’t jive for me. I didn’t believe it when I read it. I didn’t believe it when I read Die Hard. When I read Die Hard, I was like, “Nobody’s going to believe this guy can run around in a fucking building with his no shoes and take on all these guys.” When I saw the movie, it’s like, “Oh, this is great!”

Maybe it’s that I know too much — I’ve made so many movies, and I know what goes on behind the scenes — but sometimes I can’t have that suspension of disbelief for some things. Certainly, King of New York requires a certain amount of suspension of disbelief. School Daze requires that because suddenly they break into song. I was able to go with those things, but it’s just those three pieces, for whatever reason, I just was like, “No, I don’t get it as an actor.” It wasn’t about my character in Pulp Fiction. It was about the way in which the heroin thing was delivered. And the whole fucking thing with the hypodermic and the adrenaline shot? No.

Tarantino says he offered it to you, but your agents at the time told you not to take it because it wasn’t a leading-man part.

No, no. It is a leading-man part. Fucking Sam [Jackson] walks away with the movie! Sam fucking sticks the movie in his pocket and walks away from it, walks into a fucking leading-man career. What are you talking about? It’s a great part. It wasn’t about the part. It was about the totality of the thing, where I was like, “Why is it that the biggest, blackest, baddest motherfucker in the whole thing gets fucked in the ass by two country-ass motherfuckers? Explain me that.” But when you talk to Ving [Rhames] — I know Ving from back in the day — he was like, “You know what, Fish? You have no idea how many cats have told me, ‘Thank you for doing that,’” and appreciated the fact that I was able to do that because some cats, that happens to them, and they’re still men. Just because you get raped, doesn’t make you any less a man. I wasn’t evolved enough to actually realize that, or to even think about it in those terms, but Ving was. Everything’s not for everybody.

And it depends on where you are.

Yeah, where you are, who you are, and what’s important to you, what you’re focused on.

Relatedly, my understanding was that you were going to take [Samuel L. Jackson’s] part in Die Hard With a Vengeance and that you had asked for $1 million.

Oh no. I was already cast in Die Hard 3 and then, at the 11th hour, they were like, “Nah, we got Jackson.”

Was that about money?

I’m sure that was about money, because I was probably getting more money than Sam then. That was about money then. We sued them. I had a whole lawsuit that went for two years against Cinergi Pictures behind that.

Oh, I didn’t know that.

Yeah, well, it wasn’t public knowledge.

How did it end?

There was a settlement. I got compensated for that.

It sounds like a story about the way Hollywood studio executives in particular may have pitted Black men against one another.

Well, I guess that’s one way of looking at it. I never took it personally like that. It wasn’t about Sam. It was about how they had a deal with me that they reneged on in the 11th hour. I’m all good with Sam. I’m so happy. At the end of the day, we went through a process, we went through a two-year thing, we got some kind of compensation, but the best thing to come out of it was I was so pissed off I sat down and wrote a play.

Riff Raff.

Yep. That was the best thing that ever happened. That’s what came out of that. I haven’t written one since. Maybe I just need to lose another couple of jobs. You think about it — that was ’95, so I wrote Riff Raff, did it, then I did The Tuskegee Airmen, then I did Othello. After I did Othello, I was like, I don’t have to act ever again. Between King of New York at 29 and Othello at 34, I don’t ever have to try to prove anything as an actor ever again. If I could play them two motherfuckers, I don’t have nothing to prove.

What’s Love Got to Do With It has two really remarkable performances from you and Angela Bassett, and it’s also an interesting film after Me Too. I was curious if you think it holds up in the current context.

I hope it does. I would hope that her story is relevant because we know this is still going on. As long as we’re living with domestic violence, I think it should hold up. And thank God for the day when it doesn’t, really.

From what I gathered, you rewrote a lot of Ike Turner’s lines in the script.

I rewrote a lot of it. I was trying to humanize him, because in humanizing him, you deepen her. It’s a complicated relationship when it’s abusive and one has dominance over the other and is manipulative, and I just felt like for him to be just the villain wasn’t going to be good enough.

On Inside the Actors Studio, you said that while shooting the rape scene, you’d asked the director, Brian Gibson, that there be only four takes and no close-ups. Can you say why?

Well, it’s really simple. There was a lot of discussion about what Angela would be wearing in that particular scene, and there were things they were asking her to wear that she wasn’t in agreement with. She finally got that part of it settled. Then we got to the actual rape in the booth, and I just felt that the less you saw, the more it would activate your imagination. And because it’s so violent, really, you don’t want to do it too many times. You can’t just do something like that without hurting yourself emotionally. I was like, Four takes. You can be out there, but you can’t come in here.

Am I right to assume that it was about protecting you but also protecting Angela?

It was about protecting me and Angela, but mostly about protecting Angela.

Do you feel she was protected on that set?

Well, I turned the movie down five times. The reason I said yes finally was because Angie was going to play the part. I had seen Angela do Joe Turner’s Come and Gone here on Broadway, and I thought, Damn. We almost made a movie after that in 1988. It was called Dessa Rose. It was me and Angela, the late Natasha Richardson, and a guy named Tony Todd — who went on to do the Candyman movies — [who] were the four leads in this movie. Cicely Tyson was also supposed to be in it. It didn’t get made, and then we did Boyz n the Hood together. We had that great scene in the restaurant. I had been a fan, and I didn’t really think the writing was — but I knew that her in this role was great, and I felt like I could be helpful to her. I used to say my old job was just, Look, all you motherfuckers, move out the way, Angie’s coming.

Have there been roles that were difficult to shed afterward?

When I was working as a kid, that was hard. Of course, Apocalypse would have been hard because I was there for two years, so it was hard to give that up. But once I got to be about 26, 27, it wasn’t that hard anymore. Because it was hard to get a job, and jobs were far and few between. You always felt better when you had a job than when you didn’t have a job. By the time I was about 27, 28, I figured out, Oh, what you’ve got to do is you’ve got to get another job before this job ends, then you’re good.

There are a lot of projects that have never happened that sounded fascinating. One was detective Pharaoh Love.

I’m still trying to figure out Pharaoh Love, dude. I feel like now is the time. When you think about LGBT rights and issues, and where we are with that right now, it feels like this could be a good moment for that story to be told.

Do you still have the option?

Yeah. We still do. You just keep redoing it. In fact, I’m thinking that we’re going to use a model that we just did. We did this thing called Bronzeville, which we’re developing now, with Apple TV. It was a podcast. It’s a radio play, really. It’s a 1940s Chicago gangster thing on the South Side of Chicago. I think it’s possible for us to do the same thing with Pharaoh Love, which is based on a book called Queer Kind of Death: P.S. Your Cat Is Dead about this closeted gay homicide detective in New York in the West Village in 1966. On the outside, these cats present straightish, but their interior world and the world that they occupy between the West Village and Park Slope in Brooklyn, and those other little pockets, is where they live out loud and in color. We just thought, This is Felliniesque. It would make great movies. I mean, it’s a fun, fantastic, wonderful world that we have not seen, and I just dug it. I just thought this is cool shit.

And you would play Pharaoh Love?

When I was in my 30s, I would have played Pharaoh Love. Ideally, I would love Laverne. You know Laverne?

Laverne Cox?

Yes, who played Frank-N-Furter. You see Laverne as a dude, as a detective, who makes the transition to being the drag performer because that’s what happens to Pharaoh Love. He starts out as a closeted detective, and there’s this murder that happens, and he’s trying to get to the bottom of the murder, and he realizes that the murderer is this dude that he’s actually falling in love with, so he goes about creating an alibi for the dude, sends somebody up the river for the murder, but lets the guy know, “You belong to me now, otherwise your ass is going to jail.” That’s book one. By the time book three comes around, he’s in full drag, and he’s performing.

Are there other projects that you feel like were ones that got away?

Oh, obviously the Hendrix thing would have been great to have done that. Andre Benjamin was great as Jimi Hendrix. I would have loved to do that.

Was that a rights issue?

[Pause] We’ll talk about it later.

It sounds like acting is a moment where you could be free. Then there’s the industry, which is about money, and other people’s perceptions of your abilities. How have you dealt with that tension of wanting to feel free in the work but then being constrained by industry expectations?

Well, I’ve never felt constrained by any of it because at the end of the day, I know this to be true: Between action and cut, it’s mine. Now, it’s only 30, 40 seconds, but between action and cut, it’s mine. What you want to do with it after that is up to you, but between action and cut, between when the curtain goes up and the curtain goes down, it’s mine. You can do what you want to do, you can say what you want to say, but you’re not out there unless you’re out there with me.

There’s a lot of stuff that happens in getting to “action.”

All the stuff that happens to get there is what is required to get there. I mean, shit doesn’t happen by itself. It is show business, but the show comes before the business when you look at the word. Now, people on the business side will tell you the business comes before the show. I get it. I have no problem with people doing their business, and I have no problem with people asking me to do business on behalf of the show. My heart is in the show. That’s where my heart is. That’s where I really, really live. I understand the business, and I can do some of the business. Is my heart in it? Can I get my head around it and can I do the things that I need to do? Sure.

Was there a moment when you felt like you had the power to make projects happen from the business end?

Part of the CSI deal was I had a first look deal [for] my company Cinema Gypsy with CBS, which meant that we could bring them any project that we thought they would be interested in. That was great. I did that series for three seasons. I hired an executive, a woman named Rose Catherine Pinkney, to find material, to find writers, and we attempted to make sales of many different shows. I would say about a dozen. We got close to selling one, but none of them really took. But in those first three years, I had no idea what I was doing. No idea. It was after three years that I realized, Oh, I’m auditioning again, only I’m auditioning as a businessperson. I’m not auditioning as an actor. I’m coming in as a producer, going to the buyers, “Hey, want to buy this today? Hey, look what I got for you today.” I realized it’s going to take seven years for them to get it and to take me seriously because I’m an actor first, so I’m coming in the room, and what’s happening is they’re having their Laurence Fishburne experience. They’re having their Morpheus experience, they’re having their, “Oh, you know who I met today? I had that experience with that guy.” Nobody is taking me seriously as a producer. It’s, “I love that movie. Tell me a story.” All right. I realized, All I have to do is sit here for seven years. When I’m here for seven years, these motherfuckers will finally wake up and go, “Oh, no, he’s not just a guy from the movie. This guy really wants to be in business.”

You’ve always been really good at mimicry. Did you always know that you could use your voice to impersonate other people?

Yeah. I figured out really early on what I could do with my vocal instrument, yeah.

As a kid?

Yeah. It was just in front of the TV. There were voices coming at me in the TV, and I would just send them back. Mel Blanc, Bugs Bunny. The little black duck. Whoever it was. Then, of course, I had ears for the sounds because I grew up in Park Slope in Brooklyn, which was really, really mixed. It was people from the Caribbean, there were Puerto Ricans, and there were Jamaicans, Irish people, Italian people, English people, Chinese people, and Japanese people, and most of the kids were first generation. The parents were all immigrants, so I would listen to the parents, and do their sound. It was just my ears.

That was acting school.

Yeah, definitely. That and going to the movies. My dad would take me to see proper movies. He wouldn’t take me to see kids’ movies. He would take me to see real movies. McQueen’s movies, John Wayne’s movies. Then he would take me to see Poitier’s movies, Charles Bronson’s movies. I mean, he even took me to see Hell in the Pacific with Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune at 8.

What was your relationship with Sidney Poitier like?

Poitier was definitely one of my mentors. I had these great moments with Poitier in the ’90s when I was doing this movie Event Horizon in London, and I got to spend three days with him, just the two of us. He gave me some great pieces of life advice. When I started, I was doing One Life to Live here in New York. I was 10, 11 years old, a single-parent household. I didn’t have the nicest clothes, all that shit, and I wound up on a TV show. All the kids in the neighborhood would be like, “Hey, movie star. How come you’re dressed like a bum? What the fuck?” That kind of thing. Then coming up in the ’70s, the ethos for film stars changed because now this is the day of Robert De Niro, and Al Pacino, and Dustin Hoffman, and these guys are actors first. Their personal life is not what they’re selling. In the old days, the movie star had to do the thing, and these guys are of the Brando school of “My personal life is off limits to you.” I felt like I was in that kind of tradition and culture. It’s about the work for me; it’s not about the starry-eyed shit. I’m not chasing an endorsement. I’m not trying to push Chesterfield Kings, or Wheaties, or whatever the fuck it is. I’m not comfortable with this word star or movie star. I’m comfortable with being an actor. I’m comfortable with being an artist.

So, I’m having lunch with Poitier, and we’re eating. He goes, “So, you have to understand, when you’re a star, you have to take care of yourself. And you are a star.” At which point, I’m going, Fuck. If this guy’s telling me that I’m a star, I just can’t ignore it. I can’t act like it’s not real. Because he was the biggest movie star in the world in 1967. He’s not talking about some shit he heard. He lived it. He knows what he’s talking about. I had the same kind of moment with Warren Beatty, who said to me, “It’s very hard to be the son or the daughter of a movie star,” because I had a daughter who went through some stuff. I went, Well, fuck, he’s not telling me something he heard. People had said that to me for years. I was like, “You don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about. You’re not a fucking movie star.” But when Warren Beatty tells you, you kind of got to go, Oh, shit, he knows what he’s talking about. I’ve got to recalibrate now.

What does that reorientation look like?

It’s just about recognizing that there is a perception that people have of you and people react to you a particular way. People get really happy when they recognize me and see me. They break out into these huge smiles. For years, I couldn’t figure out why. Because I’m not on the movie screen — I’m just walking down the street; I’m in the fucking dairy aisle at the grocery store. You don’t need to smile at me that hard. I’m not onstage performing for you. I’m trying to find the 2 percent-fat yogurt. It was just about recalibrating and recognizing that that’s not people trying to get in my space. That’s not people trying to define me. That’s just people seeing me and being surprised and being really, really happy that they’ve seen me. That’s all. And just being all right with that. But you never get used to it, just as a human being. No one wakes up in the morning going, Holy shit, it’s me.

What were your thoughts when you first read the script for The Matrix?

I thought this was the most original thing I’ve ever read, and I can’t wait to do it. Because I’m a science-fiction head anyway, so I never had any questions about whether or not it worked structurally, thematically, or anything on the page. There were no red flags on the page for me at all, and then when I met Lana and Lilly, they said they wanted to make a live-action anime. I was like, “Yes, please.” I got it. I totally got it. I didn’t need them to explain what they were trying to do.

You’ve talked about putting on a “mentor suit” for roles like Morpheus. What was the process for putting a voice like his together?

It was interesting. The mentor thing happened to me before with Boyz n the Hood. I didn’t realize it had happened. So once I had gotten the gig, I was like, For me, it’s a combination of Rod Serling and Leonard Nimoy. There’s probably a little James Earl Jones in there somewhere, but it was really those two guys I was thinking about [while] doing it.

What is The Matrix about to you?

So many things. I think the most elegant answer is it’s the old story in a modern context. It’s the One, the Christ, the Buddha, the Godhead, the fully realized being told through the digital age.

Did the Morpheus role ever become too big for you?

It is probably the role that I’ll be best remembered for, which is great; it’s not the only thing I’ll be remembered for, which is better. He’s fucking amazing. What I get with him is I’ve got Darth Vader in this hand, and I’ve got Obi-Wan in that hand. I’ve got Bruce Lee, I’ve got Muhammad Ali shuffled in there, and I got kung fu. It’s pretty good. People confuse me with Morpheus. They think I am Morpheus. I am not Morpheus. I’m not even close.

It does feel like you’re often playing the wise black man.

Or the magical Negro. However you want to describe it, yes.

How does that sit for you?

It’s fine. There’s nothing wrong with having a little wisdom. There’s nothing wrong with people assuming or people perceiving that you have a little wisdom, and that you are strong, and that you are intelligent, and that you are fierce, and that you have a little danger. There’s nothing wrong with that. This is great. This is lovely.

Are you doing The Matrix 4?

No. I have not been invited. Maybe that will make me write another play. I’m looking for the blessing in that. I wish them well. I hope it’s great.

*A version of this article appears in the August 17, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!