In Mel Brooks’ classic 1960s NBC comedy Get Smart, secret agent Maxwell Smart would reliably utter five words whenever his weekly bumbling miraculously avoided a calamitous outcome: “Missed it by that much,” he’d deadpan. Netflix co-CEOs Reed Hastings and Ted Sarandos are a lot more competent than Don Adams’ iconic character, but this week the duo are probably feeling about as lucky. Despite some last-minute speculation that Netflix’s forecast of a two-million subscriber loss during the second quarter might actually prove optimistic, the streamer instead beat its own gloomy benchmark, bleeding a still-bad — but not catastrophic — 970,000 customers over the spring.

But while the worst case scenario was avoided, Netflix still faces many months of turbulence as it adjusts to a new normal.

During an earnings interview with Douglas Anmuth of JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tuesday, Hastings himself conceded as much, admitting it’s “tough” to consider the loss of nearly one million subscribers — the worst quarter in Netflix history — as some sort of success. “Our excitement is tempered by the less bad results,” he said. Indeed, despite Stranger Things 4 breaking all sorts of viewership records, and Ozark dropping its final batch of episodes, Netflix was still unable to generate enough new signups to offset the loss of millions of customers. It’s an outcome which would have been unimaginable at the start of 2022.

What’s more, things look even less sunny when you drill down into Netflix’s earnings report. The streamer parted ways with a whopping 1.3 million subscribers in the U.S./Canada market between April and July — nearly two percent of its total member base in what’s known as the UCAN region. And in the Europe/Middle East/Africa region (aka EMEA), Netflix lost roughly 800,000 subscribers. Until relatively recently, many analysts still thought UCAN and EMEA both had room for robust growth. That they’re both now starting to shrink suggests that’s unlikely. What’s worse, it might also mean Netflix’s long-term growth potential in younger markets such as Asia and Latin America may be much smaller than many had presumed.

This low-growth realization is, of course, why Netflix stock has lost so much value over the past six months. Dreams of the company building a global base of 700 million or even 800 million paid memberships now seem far-fetched, given the company has stalled out at around 220 million. Netflix is working on ways to get growing again, most notably cracking down on password sharing and introducing a lower-priced option for folks who can tolerate a little advertising. But these initiatives won’t really start coming online in most of the world until mid-2023 or 2024. And even once they do, it’s hard to see either idea being enough to get Netflix anywhere close to realizing the ambitious subscriber goals of a few years ago.

Even if they’d never admit to it out loud, I’m guesing Netflix execs have already lowered their own internal growth expectations, too. It would take some significant new development in the streaming universe — such as a major rival exiting the business, or linear TV suddenly collapsing — to get Netflix growing robustly again in mature markets such as EMEA and UCAN. No wonder then that regular linear TV doomsayer Hastings was back on his … soapbox Tuesday, confidently and very casually predicting “definitely the end of linear TV over the next 5, 10 years.”

As annoyingly cocky as Hastings’ death-to-linear comments are, particularly given his own company’s present situation, I don’t think he or Sarandos are actually expecting they can “win” the streaming wars by putting linear TV out of business, at least not anymore. (Was that the plan ten years ago? Probably!) Instead, the recent waves of layoffs, the sudden move to finally agree to advertising, the decision to basically freeze spending vs. continuing to escalating the content wars — all these moves are indications Netflix has readjusted its mindset. You’re probably not going to see Netflix hand out many new nine-figure contracts to showrunners anytime soon. It will still spend stupid sums of cash on movies like The Gray Man, but the days of going after any project it wants just by writing a check are over (and probably have been for quite some time). Netflix’s leadership team knows what everyone else does: It’s now a fully mature business instead of an emerging disrupter, and that means acting accordingly.

One word of caution though: The moves Netflix are making to address its growth slowdown are not without risk. For example, while limiting how many users can share an account will surely yield some new subscribers, it could also end up alienating folks who’ve been told for years it’s perfectly OK to give their passwords to friends and family. Netflix has historically been a beloved brand by younger consumers, many of whom have been using it since they were teens (or younger). If it pushes too hard to maximize revenue and please its masters on Wall Street, it runs the chance of coming off as the new version of the cable company.

The Case for (Even More) Change at Netflix

While Netflix has taken serious actions to reverse its slump, some of its fiercest critics think it should be changing even more, and more quickly. Sarandos and Hastings maintained a mostly “This Is Fine” demeanor during the earnings interview Tuesday, but there’s a case to be made that perhaps they should have been more blunt with Wall Street and Hollywood about the challenges ahead. Similarly, there exists a very loud chorus of critics from various sectors (financial, entertainment, journalism) which think Netflix is committing entertainment malpractice by not becoming more like traditional TV network and movie studios by, say, releasing episodes of shows on a weekly basis or putting its movies in theaters for 45 day before they stream.

But in the letter to shareholders which accompanied this week’s earnings report, Netflix seemed to scoff at the suggestion it needs to change any more of its core practices. It specifically pointed to its distinct ways of doing business as advantages, not liabilities. “As a pure play streaming business, we’re unencumbered by legacy revenue streams,” it wrote, adding its “focus on choice and control for members influences all aspects of our strategy, creating what we believe to be a significant long term business advantage.” It was a pretty clear and direct “take me as I am” message to doubters, so much so that I half-expected Hastings and Sarandos to start belting out a version of “This Is Me” from The Greatest Showman on the earnings interview. (Alas, no such luck.)

It’s also understandable: Netflix became the planet’s biggest platform by not being traditional TV (see also: HBO in the 1970s.) And when TV partisans rail against the fact that so many streaming shows are now 10-hour movies, or that episodes don’t have time to sit with audiences with the binge model, I think they forget that many consumers disagree, and that binge-released shows such as recent buzz hit Heartstopper can still find word-of-mouth success.

Still, Netflix’s understandable pride in its revolutionary roots sometimes borders on counterproductive stubbornness. Remember, it took losing one-third of its stock valuation for Netflix to agree to advertising. A company which lived up to its own mantra of giving members choice would have realized years ago that cost-conscious consumers would rather watch a few ads if it meant saving $50 a year.

Similarly, centering members might mean admitting that as groundbreaking as the binge model was, many real people (not just critics) actually do like watching shows which release episodes weekly, particularly if those shows also churn out 20+ episodes every year. Why shouldn’t a modest percentage of the 100 or so series Netflix makes each year follow the broadcast TV model? Netflix already does this with titles it acquires from other platforms and distributes internationally, like the South Korean smash Extraordinary Attorney Woo, which debuts new episodes twice each week on Netflix. It should do the same with some of its own originals, too. Because, you know, choice.

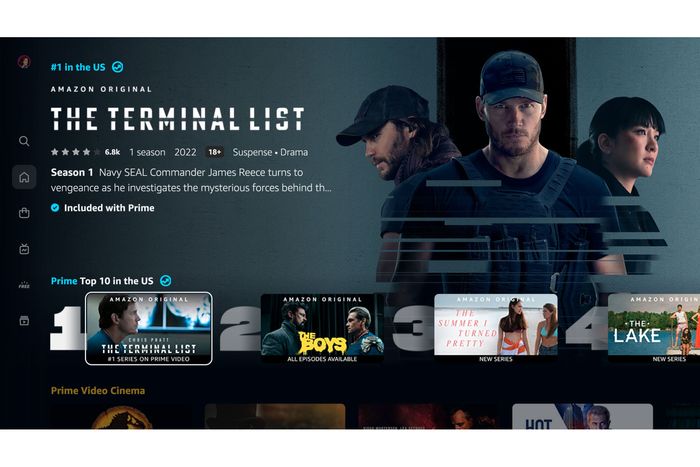

Amazon Prime Video Finally Looks Decent

An Amazon source emailed me a couple weeks ago to let me know some news was coming down the pike that would make me very happy. I immediately replied, “Please tell me this is about Prime getting a new UI.” Dreams really do come true: On Monday, the Amazon-owned streamer confirmed that it had begun rolling out the biggest redesign of its user experience in nearly a decade. The move came after years and years of complaints from customers, and just before the late summer launches of Thursday Night Football and Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. You may have already gotten the updated interface, but if not, I talked to an Amazon product exec about all the changes and how they came together earlier this week. You can read that story here.

Prime Video is moving users to the new interface in waves, and sadly, my Apple TV and Roku devices hadn’t gotten the updates as of Wednesday, so I can’t offer any hands-on insights about the changes. From what I’ve seen, though, it’s clear the streamer isn’t trying to reinvent the wheel or win any awards for innovation. The new UI borrows liberally from concepts executed years ago by Netflix and Hulu, but with just a dash of Amazonian flair (like the continued blending of content included with a subscription and stuff available to rent or buy). Honestly, I’m OK with that, because streamers get in trouble when they overthink design elements. Folks just want to be able to find something good to watch, and more importantly, for the app to just work. Crowd up your UI with too many bells and whistles and you dramatically increase the risk of bugs sneaking in and crashing the system. For too long Prime was hampered for being too bare bones, so as its content offering exploded over the past five years, users had trouble even noticing something new had been added to the platform. The new interface hopefully fixes that problem.

Still, that doesn’t mean Amazon — and every streamer — should stop working to improve their user experience (or UX in industry parlance). Whether it’s glitchy apps that don’t work properly on a given device, crashes caused by too much traffic or just poorly-designed layouts or functionalities, bad UX is a major source of customer complaints. You can have the best shows and movies on the planet, but if the simple act of fast-forwarding through a title prompts users to take to Twitter in frustration, you’ve just dramatically upped the odds of that customer canceling their subscription.

Similarly, as big companies move increasingly to create one-stop designations for all their streaming content, that big infusion of new programming is going to require platforms to get a lot smarter about making sure customers can find it all. It’s all well and good that Discovery+’s thousands of hours of unscripted series will soon be accessible on HBO Max, but if it’s not properly integrated into the Max universe, the Warner Bros. Discovery streamer runs the risk of overwhelming audiences who’ve come to appreciate the upscale vibe the streamer currently gives off. Disney will face a similar challenge if and when it mashes together Hulu and Disney+ (though they’ve basically already done just that in India and much of Europe).

Thankfully, most streamers have finally realized what Netflix has known for years: While it costs a lot of money to make sure your product runs smoothly and your design keeps up with expanding content offering, it’s an investment worth making. And while Amazon may have taken a bit too long to remodel Prime Video, at least it got there. A few streamers still have major work to do on the user experience front — Peacock and Paramount+ jump immediately to mind — and hopefully they will move quickly to give their subscribers a similar upgrade.