In 2019, at age 38, I started taking Truvada. With the threat of contracting HIV drastically reduced, it rapidly became clear to me that my approach to love and sex had been dictated mostly by fear: Instead of conceiving of my love life as a romantic comedy, I thought of it as more of a horror movie. The result of this realization was the essay excerpted below, ÔÇ£Blood, Actually,ÔÇØ in which I tried to understand the effect HIV/AIDS had on my generation ÔÇö especially our difficulty forging intimate connections.

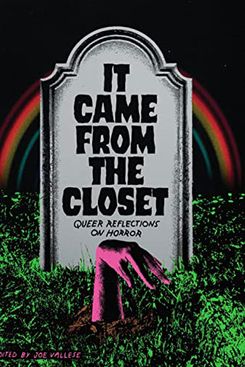

IÔÇÖm not alone in seeing horror, for good and for ill, as a quintessential part of the LGBTQ+ experience. Earlier this month, Feminist Press released an anthology called It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror, in which I and 25 other queer and trans writers exhume and examine popular and lesser-known horror films. Guided by editor Joe Vallese, we poke, prod, and reanimate the horror films we love to explain moments of vulnerability and strength in our own lives. Each essay is a banger, exploring sometimes humorous, often heartbreaking themes, from growing up in hostile territory to looking for yourself in films that exclude and pathologize queerness.

Excellent film theory and historical analyses of gender and sexuality in horror films already exist, of course, and this strange little book is indebted to them. But It Came From the Closet forgoes simple conclusions in favor of much thornier, more difficult conversations with readers. The horror film becomes the tool, at some times blunt and other times sharp, that expands empathy for ourselves and other generations of queers, continuing the fabulous tradition with a new and diverse generation of writers.

EXCERPT FROM 'IT CAME FROM THE CLOSET: QUEER REFLECTIONS ON HORROR'

When my mother and father were still in love, we lived on the marshlands of the Intracoastal Waterway, and you could smell the sea and watch the buoys that marked our crab pots bob like severed heads in inky water. I was working up the nerve to check the pots on my own one day, even though I was scared of the crabs they imprisoned, when I heard my mother scream,┬áÔÇ£Cottonmouth!ÔÇØ from the deck. Terrified, I sprinted back toward the house. Our handsome collegiate gardener, my first crush, was trimming the azalea bushes in the front yard, but he grabbed a shovel and made his way to the back, where danger lay coiled, head shaped like an arrow, ready to strike. The sliding glass door framed him, and I enjoyed the long, uninterrupted view of him┬áwearing not much more than work boots, a pair of tight jeans, and a thin layer of sweat. He looked just like Mark, the counselor from Friday the 13th Part 2. In one decisive motion, like Zeus hurling a thunderbolt, my hero severed the snake in two. Wiping the sweat from his brow with one gloved hand, he scooped the pieces into a garbage bag, and peace was restored. I wanted to thank him, to give him a kiss for his gallantry, but I resisted.

When my parents divorced, we moved to my motherÔÇÖs home: a twist in the road, a clearing between tobacco and cotton fields. There were more snakes, no father, and no Mark to save us. Instead of counting out daffodil bulbs for her garden, she now counted her fears about all the ways she was afraid to ruin us. I collected her fears like she collected our baby teeth in her jewelry box: LSD-laced Cracker Jack tattoos, suffocating to death in a refrigerator,┬ákidnapping, home invasion, the constant threat of poverty.

When I was 7, I came out to our neighbor, who told my mom, who confronted me. I denied it, pretending I didnÔÇÖt know what she meant. I planned to hang myself from the banister with my white karate belt.

Whatever happened next is chained to the bottom of my memory, struggling to breathe, waiting to resurface. Everything fades to black.

EXT. CAMP CRYSTAL LAKE ÔÇö EVENING

The screen door slams shut just as the rain begins to pummel the camp. Tiny ricochets turn to a constant roar as Mark, the beautiful brunette counselor in a wheelchair, glides down the ramp to search for Vickie, who wanted to change before they went off together to make love in an empty cabin. As she runs around in the rain in her brown satin sex panties, Mark starts to worry: What is taking her so long? Menacing music scores the moment that the machete appears from nowhere, slicing into his gorgeous face, the force of the blow so powerful that it sends him flying backward down not one but two flights of stairs, the latter impossibly long, descending into nothing. The screen freezes on the back of his head with the machete lodged in the front. Flash to white. Smash cut to the next teen sacrifice.

The murder of Mark, played by Tom McBride in Friday the 13th Part┬á2, an out gay actor and self-described ÔÇ£A-list gayÔÇØ who went on to die of an AIDS-related illness in New York City, was not the first time I learned that┬ásex equals death. On the way to school one day, my mother handed me and each of my brothers our own copies of People with Kimberly Bergalis on the cover. The photo of the thin sorority girl whoÔÇÖd allegedly contracted HIV from her homosexual dentist, David Acer, bore the title ÔÇ£The Dentist and the Patient: An AIDS Mystery.ÔÇØ My mother wanted each of us to read it so we could talk about it as a family. The article discussed how KimberlyÔÇÖs mother worked with patients living with HIV and AIDS in a Florida clinic and recognized the hollow cheeks as a telltale sign that something was wrong with her daughter. No one knew how she could have contracted it because she claimed to be a virgin waiting for marriage and she didnÔÇÖt use intravenous drugs. The only possibility: Her homosexual dentist must have intentionally infected his patients as an act of violence and rage motivated by his own impending death. This was never proven.

At this point, my sweet fantasy of marrying a Mark of my own and living together forever in a snake-free castle decayed into the tobacco fields we were passing on the way home. Whether the Bergalis family meant to ignite this gay panic or not, gay men were ripped from the shadows and elevated to public enemy. The word AIDS slashed across all the headlines, the bold red letters made every trip to the grocery store a test of endurance, avoidance. News programs showed Lady Diana visiting patients living with AIDS and all I could see was myself, my skeleton protruding through my thin skin, eyes sunken in, reaching for her hand. People applauded her for touching the patients and treating them like human beings as if sheÔÇÖd performed a feat of strength. President Reagan didnÔÇÖt even acknowledge HIV/AIDS for six years, and only because Elizabeth Taylor manipulated him into it. The ÔÇ£personal responsibilityÔÇØ doctrine of the Reagan era taught Americans that fault lay with gay men and their enablers and AIDS was a just cure for their existence. Nancy Reagan stood by in her bloodred dresses, red as an AIDS ribbon, red as gore. Often the evening news featured our United States senator Jesse Helms, my motherÔÇÖs favorite politician, suggesting that people with HIV should be quarantined or William F. Buckley calling for gay men to be identified and tattooed on the buttocks, and it taught me to hide my feelings. I would escape to my room, where I created elaborate versions of ways I would eventually die when it was my turn. Gay blood must be toxic, and I visualized it┬áclogging my veins like black Jell-O.

At bedtime, every night, I petitioned Jesus not to let me die of AIDS.┬áSleep felt like a trapdoor for death, a time for all of my worst fears to creep in. Sometimes, in the darkness, I counted my heartbeats and wondered how many I had left. I lay awake thinking about my abdominal cavity, a butcher-shop case of throbbing organs writhing together. I categorized each spasm, waiting for my insides to turn on one another and then on me. I obsessively counted the number of times I might see my family members again in my┬álifetime, feeling guilty for wanting to run away from them all, dreading the day my mother would acknowledge my homosexuality and condemn me or when my pediatrician would out me by diagnosing me with HIV. I would brainstorm escape plans to New York, tracing the route IÔÇÖd walk in an imaginary atlas. I wrote down lies in my diary with the flimsy lock to throw my mom off my path (I donÔÇÖt think she ever read it). The only way to keep the┬átrapdoor sealed was by staying up late reading V. C. Andrews novels about incest, madness, and damask. And when I was older, I watched horror movies.

I started with Nightmare on Elm Street, Halloween, Texas Chainsaw Massacre. IÔÇÖd convince my mom or dad to let me rent whatever I wanted. They were too guilty or too tired to object to my selections. Entering the horror-movie section at Videomax, decorated with fiberglass and papier-m├óch├® Dracula and┬áFrankensteinÔÇÖs monster and the Mummy, felt like the first exercise in bravery. Next came looking at the scary art on the box covers, then reading the┬ádescriptions. Every tiny step felt like training for the fear that I was learning to live with, incremental poisoning to gain immunity.

Each villain was deformed, disfigured by scars, and masked. Often these figures were the objects of early shame for some disability outside their control. Pushed to the fringes, they became experts in the behavior of their victims. There was something about the simplicity of Friday the 13th that especially appealed to me. In the original film, JasonÔÇÖs mother is the killer. It opens by putting the audience into Ms. VoorheesÔÇÖs point of view as she kills trysting counselors in the boathouse. Grief-stricken and unhinged, she attempted to assuage her grief about the accidental drowning of her son by murdering any new counselors who wanted to reopen Camp Crystal Lake. In her mind, all of the teens deserve their grisly fate ÔÇö they should know better. After his mother is murdered by Alice at the end of the first film, Jason Voorhees takes over the blood feud, avenging her death. Armed with his relentless silence and tenacity and a white hockey mask, broad and pocked like the surface of the moon, he dispatches his victims, one or two at a time.

As I got braver, I watched all of the Friday the 13th films. Rather, I studied them. I memorized the names of the actors, the characters, and all of the creative ways that Jason would kill people. If I focused on the trivia long enough, I could escape the true horror that kept me awake at night. He has the most kills of any slasher series, and he lives in a dirty shed in the woods near ÔÇ£Camp BloodÔÇØ (except when he went to Manhattan on a shitty cruise ship and when he went to space and when he went to hell), so creativity is necessary. Among JasonÔÇÖs improvisational weapon choices: a pitchfork, an RV wall, a space anchor, an electrical box, a tent stake, a noisemaker, a trimmer with a saw-blade attachment, a flaming machete, a screwdriver, a tree pruner, a heroin needle, a fire poker, a wrench, a harpoon, a radio antenna, a scythe, a liquor bottle, a claw hammer, a fence post, a spaceship-hull breach, a camper-filled┬ásleeping bag, an oil drum filled with trash water, hot stones from a sauna, a deep fryer, a bone saw, a signpost.

Slasher films gave me a way to order the violence and death that occupied most of my attention. My toxic blood seemed less terrifying when I saw fake blood spilled onscreen, knowing that it was probably chocolate sauce, corn syrup, or pixelated gore. If the blood was fake, then maybe, just maybe, all of reality was fabricated, and knives and ice picks always retract, bullets are always blanks, and no one is ever murdered by a machete-wielding killer. No one is ever really harmed. Anxiety is temporarily relieved as the credits roll, a vulgar catharsis. When real fear creeps back in, just rewind the film and start again.

Rewind the film. Start again. Go to Crystal Lake in your mind.

You might think that once youÔÇÖve seen one Friday the 13th, youÔÇÖve seen┬áthem all. But you would be incorrect. The finer points distinguishing each film may seem negligible to a layperson. The story is told repeatedly, repetitively, almost obsessively, every time. A group of attractive teenagers arrives at┬áa reopened summer camp, no trace of the murders from the previous summer.┬áRepainted cabins flank the lake, which seems to be impossibly high in naturally occurring lithium, given the chipper attitudes of each fresh set of victims. The endlessly refreshed archetypes are all guilty of something outside of their┬ácontrol. ThereÔÇÖs always the funny one, the hot one, the stoner, the jock, the nerd, the biker, the clown ÔÇö and they all want to get laid. Except for the ÔÇ£final girl.ÔÇØ

Everyone recognizes the final girl. The term is so commonly used that if you use it around even a moderate horror fan, you might see their eyes roll back in their heads. The final girl is beautiful ÔÇö not too beautiful ÔÇö smart, funny, charming, wholesome. But sheÔÇÖs often aloof or possesses some skill or ability or insight that ends up saving her in the end. Something she may or may not value about herself. She is the ideal victim. Does anyone want to be the final girl more than the young closeted queer? Brimming with unseen inner power, waiting to demonstrate her strength.

During the last act of each film, the final girl and Jason lock into a grisly pas de deux. Each makes their move, struggling for primacy. Each fulfills their function. The coda is almost always his unmasking, revealing the true, repulsive, unlovable face beneath the mask. But by enduring this horrific spectacle, her previous sense of safety is permanently annihilated. Once a part of the crowd, now permanently apart from the crowd, she will always be isolated by this experience, and now she must wear the mask. Her friends are all gone, and she must learn to live knowing that they are gone forever, victims of an unconscionable act of violence for which no one could prepare.

**

When I started taking PrEP, I had to mourn my past as I realized how much the fear of contracting HIV had affected all of my intimate partnerships, my sex life, and my self-perception. HIV and AIDS permanently shaped me. Now, I am one of the oldest participants enrolled in a groundbreaking medical study to develop an injectable prophylactic medication to prevent the spread. Now, HIV and AIDS are manageable conditions for those with access to care. Here in the Gulf, seroconversion rates are still alarmingly high; seeking care is still stigmatized. I struggle to locate and connect with the few elders from the generation most decimated. How can the younger queers I love understand what it was like? Is it better that they do not? I am grateful they are spared the horror.

As it turns out, being raised in a homophobic, misogynistic, racist culture forces you to behave in sociopathic ways. Nobody wants to be the poor, disfigured boy who grows up to be a serial killer. Even though I want to be a final girl, IÔÇÖm more of a Jason Voorhees. They are both survivalists in their own┬áways, but IÔÇÖve used my improvised skills to hurt people deeply, to hide from my pain. My tongue is my machete. I can be just as nimble and industrious, constantly scanning the room for threats or potential lovers, sometimes treating both as opponents as they surface. I used to hunt in gay bars or gay.com, the library stacks in college, and now I hunt in Scruff profiles that showcase floating torsos and feet and round (and not so round) asses, trapped in orderly, grid-like graveyard plots. I built a persona out of pain. But the world has changed. Now that I live somewhere more tolerant and I have more sexual freedom, what do I do with my arsenal and killer instinct? Does Jason retire when he gets sick of the murder business? Does he just want privacy at Crystal Lake? Does he murder so he can finally take his mask off and be alone in┬áhis murder shed with his motherÔÇÖs severed, screaming head? Maybe heÔÇÖs just like me, bad at ending things, more comfortable being alone and pretending to be impenetrable.

From It Came From the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror, edited by Joe Vallese. Excerpted with permission of the Feminist Press.