There were, and perhaps always will be, criticisms of how Barbara Walters did her job. But nobody could deny that her subjects trusted her to give them as fair a shake as she could, even if she disapproved of what they did, said, or stood for. Nor could they deny that Walters ÔÇö who died on Friday at 93 ÔÇö created conditions in which newsworthy comments were likely to occur. From the moment in the mid-1970s when Walters started building her career around interviewing famous people the Barbara Walters way, those interviews were almost by definition events. When WaltersÔÇÖs people called a prospective intervieweeÔÇÖs representatives to ask if their client would be willing to break whatever period of silence theyÔÇÖd been observing, they struggled to say no: That call meant you were a big deal, for better or worse. They said yes to her when they wouldnÔÇÖt say yes to anyone else because they liked the atmosphere Walters created onscreen, which carried an implicit promise that the subject, no matter how famous or notorious, would be given a fair hearing. She asked surprising questions and got answers that made headlines. Sometimes the interview itself merited a headline purely because Barbara Walters was the interviewer and her subject was a person who rarely gave interviews in which theyÔÇÖd be expected to answer questions they usually preferred to avoid.

In 2007, she interviewed Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez and asked him if it was true that hed called President George Bush the devil. Chavez replied, Thats true. Another time, I said that he was a donkey just because I think that he is very ignorant about the things that are actually happening in Latin America and the world  But who is causing more harm? He burns people, villages, and he invades nations. Twenty-two years ago, she asked the Russian premier Vladimir Putin if hed ever had anyone killed. Putin said no, but in a memorial segment on Today this past weekend, Walterss 20/20 producer Bill Sloane noted that a killers eyes looked back at her  and she felt that she nailed that one. She interviewed Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, before he flew off to peace talks with Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin, then did the first English-language interview with the two of them together. Richard Nixon let her accompany him to China and sat for his first interview after resigning the presidency in disgrace; Walterss final question was, Are you sorry you didnt burn the tapes? I probably should have, he replied. When Fidel Castro cited Cubas lack of protests as proof that citizens were happy with his leadership, Walters pointed out that protesting was illegal in Cuba. She asked Monica Lewinsky what she could imagine telling her children about her affair with President Bill Clinton. The answer: Mommy made a mistake.

Walters knew she was good at what she did and had the awards to prove it: 43 Emmy nominations and eight wins, plus a Peabody Award (for Christopher ReeveÔÇÖs first interview after being paralyzed in a riding accident). Her career stretched from NBCÔÇÖs local New York City affiliate (where she produced the 1953 childrenÔÇÖs program Ask a Camera) through ABCÔÇÖs The View, which Walters created in 1997 as a roundtable for women of ÔÇ£different generations, backgrounds, and viewsÔÇØ and executive-produced and co-hosted until 2014. But whenever she tried to describe her methods, she couldnÔÇÖt entirely quantify or explain her talent. In the 1996 documentary Interviews With Interviewers About Interviewing, she told filmmaker Skip Blumberg, ÔÇ£When you ask me questions that are about technique, or am I good at it, I get lost. But you know, there is a point in an interview ÔÇö in a personality interview, or maybe in any kind of interview ÔÇö where something goes bing! and you know that youÔÇÖve got something, and I can feel the excitement myself.ÔÇØ

Despite her long run at the top of her profession, it took a long time for its gatekeepers to come around to the idea that Walters was a real journalist with real skills. She didnÔÇÖt have much use for the unofficial playbook. She enabled newsworthy moments not by adopting an ambivalent or adversarial position right out of the gate, as her famous male predecessors so often did, but by coaxing and flattering her subjects, encouraging them to describe, defend, or brag about themselves, and making them feel she was mainly there to give them a platform to tell their version of events. Then she hit them with a question they either never expected to be asked or could not answer with rehearsed material because WaltersÔÇÖs demeanor and phrasing had rendered it useless.

Of course, they knew ÔÇö or should have knownÔÇöthat at some point Walters would crack them open like a pistachio. But when that moment came, they somehow always seemed unprepared. The late 60 Minutes correspondent Morley Safer once told me that he thought Walters was one of the most effective interviewers on television because ÔÇ£somehow, after all this time, they never see her coming.ÔÇØ

SaferÔÇÖs colleague Mike Wallace ÔÇö an actor, game-show host, and cigarette pitchman who remade himself into a journalist via a high-key┬áNew York interview show whose guests included Malcolm X, Ayn Rand, Margaret Sanger, and Frank Lloyd Wright ÔÇö was known as the Grand Inquisitor. In the 1970s and beyond, Wallace continued to be WaltersÔÇÖs most formidable competition when it came to landing a ÔÇ£get.ÔÇØ But there was a fundamental difference in their approaches, and it broke in WaltersÔÇÖs favor. Where WallaceÔÇÖs name had, as Dick Cavett put it, ÔÇ£been known to strike fear in the hearts of brave men and women,ÔÇØ people werenÔÇÖt afraid of Walters. The famous and powerful were afraid of what they might say during a Barbara Walters interview, but not of her personally, because if she wanted to interview you, it meant only that you were interesting enough to be interviewed by Barbara Walters, not that you were fated to be torn apart. There was a sense in which Walters turned the stereotyping sheÔÇÖd always struggled against to her advantage. Subjects ÔÇö especially men of earlier generations who ran corporations and countries ÔÇö assumed that if their interviewer was a woman, it meant the piece was a personality profile, not a news report, and they could let their guard down a bit. ÔÇ£Barbara Walters, in my estimation, really has the quality of reaching through to the person,ÔÇØ Wallace said. ÔÇ£She will put the person sufficiently at ease to commit themselves to her on television, and itÔÇÖs a remarkable gift.ÔÇØ

Walters was born in Boston, the granddaughter of Russian Jewish immigrants. Her mother, Dena, was a homemaker. Her father, Lou, was a theatrical producer who ran the Latin Quarter nightclubs in Boston, Miami, and New York and co-produced The Ziegfeld Follies of 1943. He was an impulsive man whose fortunes rose and fell drastically and often. ÔÇ£We moved a lot,ÔÇØ she said. ÔÇ£I went to three different high schools in my four years.ÔÇØ Because her father was in show business, he was always surrounded by people whose lives and careers were just as volatile as his. Walters was in their orbit every day and studied them like texts. According to one of her senior producers at 20/20, Martin Clancy, that made her sympathetic to people who were broke, disgraced, or otherwise out of favor: ÔÇ£ She was always aware that you could fail.ÔÇØ She also grew comfortable around stars and wasnÔÇÖt intimidated by them or by their fame. ÔÇ£I learned from seeing celebrities that they could bleed, that they had a dark side, that they had children they didnÔÇÖt see, that they had divorces or a lack of relationships,ÔÇØ she said.┬áÔÇ£It has made my life, in terms of interviewing celebrities, very different.ÔÇØ

Perhaps her most profound relationship, and the one that explains many of her major career decisions, was with her elder sister, Jacqueline, who was developmentally disabled. Her classmates made fun of her sister for the way she acted and spoke. They made fun of Barbara for having a disabled sister. This made her protective of Jacqueline (who was her only surviving sibling; her older brother, Burton, died of pneumonia at 3) and sympathetic to people who didnÔÇÖt fit in for reasons they couldnÔÇÖt control. They also partly motivated her early career decision to abandon the speech therapy sheÔÇÖd undertaken to correct her lisp. She figured it was better to just sound the way she sounded, even if it meant that Gilda Radner made fun of her on Saturday Night Live, than feel self-conscious on-camera.

WaltersÔÇÖs early life gave her a more sympathetic perspective on parenting and marriage. She had four marriages to three men, as well as some problematic relationships (with Roy Cohn, among others; in 2011, she revealed that sheÔÇÖd also had an affair with Senator Edward Brooke in the 1970s). When she asked celebrities about their sexual scandals and their disastrous relationships and marriages, she didnÔÇÖt come off a a scold, even though there were times when she couldnÔÇÖt resist saying what she knew her viewers were thinking. (When Lewinsky said, ÔÇ£Mommy made a mistake,ÔÇØ the program cut to Walters alone in a studio saying, ÔÇ£And that was the understatement of the year.ÔÇØ)

When Walters was asked to describe her own childhood in one word ÔÇö a technique sheÔÇÖd used in countless interviews herself ÔÇö she replied, ÔÇ£I guess the word that comes to mind is lonely.ÔÇÖÔÇÖ Yet she was unable to break that cycle: She often said that she felt sheÔÇÖd failed to spend enough time with her only daughter, Jacqueline Dena Guber ÔÇö an adoptee, named after her sister and mother. (Cohn helped with the paperwork.) Her daughter became a methamphetamine addict during adolescence. One time, she disappeared for a month, and Walters hired a former Green Beret to find her and bring her home. In a 2008 interview, Jacqueline told Dateline NBC co-anchor Jane Pauley ÔÇö another interviewer who considered Walters both a rival and an aspirational figure ÔÇö that she struggled with depression and alienation over being adopted and having a mother who was often absent or unreachable.

No wonder parent-child relationships were so often at the heart of her interviews. If the subject was receptive, their answers made great TV. The ABC News special Our Barbara includes snippets of Walters asking celebrities about traumas and misfortunes in their youth. She asked Woody Harrelson about his childhood diagnosis as a ÔÇ£mentally disturbedÔÇØ dyslexic. ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖve been talking to my mom!ÔÇØ he laughed, then spoke frankly about his experiences. She asked Jay-Z about the impact of his father leaving the family when he was 12. ÔÇ£I would never let anyone get close to me because of that feeling,ÔÇØ he said.

ÔÇ£Our life, really everyoneÔÇÖs life, is [about] getting to know themselves better, getting to know the world around them better,ÔÇØ Walters said. ÔÇ£We all do interviews every day. Sometimes when IÔÇÖm out at a dinner and I start to talk to someone I havenÔÇÖt met, he or she will say, ÔÇÿYouÔÇÖre interviewing me.ÔÇÖ And I say, ÔÇÿNo, youÔÇÖre saying that because this is what I do. If you didnÔÇÖt think that this was what I did, youÔÇÖd think that I was somebody curious, as so many of us are. I guess the difference is, I ask the questions that most people would really like to have asked ÔÇö at least you hope so.ÔÇØ

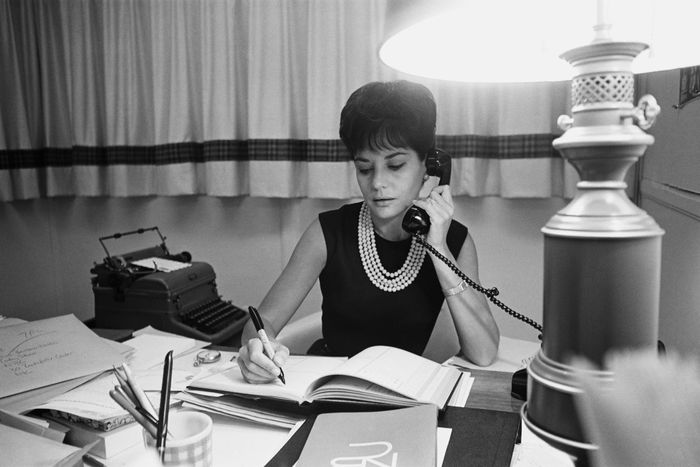

When Walters got her first network job in the early 1960s as a writer and correspondent for NBCÔÇÖs Today, the industry was literally an old boysÔÇÖ network. Its producers, reporters, and anchors saw themselves as virtuous practitioners of a stoic, honorable, manly trade and disparaged programs that focused on personalities and private lives. That attitude persisted for many decades, and despite WaltersÔÇÖs string of milestone successes, she spent her entire career carving out spaces where she could do things her way while adapting to changes in journalism, technology, and culture.

She was the first woman to co-anchor NBCÔÇÖs Today show ÔÇö a title she got only after she kept pushing the showÔÇÖs producers to accurately describe the work she was doing. Two years later, she left for ABC, where she anchored her own interview specials and became the first female co-anchor of a nightly network newscast. Her partner was Harry Reasoner, who had made his bones covering John F. KennedyÔÇÖs assassination and┬áthought of himself as a dispassionate, tough, just-the-facts reporter, as opposed to the mostly young women like Walters who were finally starting to rise to positions of influence and grasped that emotions and personalities were not only appealing but effective tools. Reasoner publicly said he didnÔÇÖt like working with Walters ÔÇ£as a person and as a woman, and privately griped to bosses that he was bothered by how she positioned herself as a celebrity in her own right.

He wasnÔÇÖt the only one who loathed Walters because he thought she girlified the news and fused it with celebrity. Many prominent male journalists (including the stars of 60 Minutes) had already packaged themselves as ÔÇ£charactersÔÇØ and used their celebrity to disarm pugnacious interviewees; when Walters did it, it was a sin against the Fourth Estate. Frank McGee, who was the Today anchor when Walters first joined the broadcast, ÔÇ£went to NBC management and demanded that she not be allowed to ask any questions of serious newsmakers, but be relegated to the ÔÇÿgirlie interviews.ÔÇÖÔÇØ A 1976 Time magazine piece ridiculed her first ABC News special, which opened with a tour of WaltersÔÇÖs apartment, and called her the yearÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Most Appalling Argument for Feminism.ÔÇØ Larry Flynt offered her $1 million to pose naked for Hustler. Gilda RadnerÔÇÖs impersonation portrayed her as a dingbat.

Stand-up comics and talk-show hosts reduced her to a bizarre one-line question that sheÔÇÖd supposedly posed during an interview: ÔÇ£If you were a tree, what kind of tree would you be?ÔÇØ It never really happened. She asked Katharine Hepburn something tree-related during a 1981 interview ÔÇö the first of four that they did over the years. But she was following up on HepburnÔÇÖs remark that sheÔÇÖd been around so long that the public had begun to see her as ÔÇ£some sort of a thing.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£What?ÔÇØ Walters pressed. ÔÇ£A tree,ÔÇØ Hepburn ventured, and Walters followed up with ÔÇ£What kind of a tree are you?,ÔÇØ a pretty basic sort of follow-up with a subject whoÔÇÖs not quite making sense. Hepburn told Walters that she didnÔÇÖt want to be an elm ÔÇ£with Dutch elm disease, because [then] IÔÇÖm withering,ÔÇØ then thought about it for a moment and said, ÔÇ£I would like to be an oak tree thatÔÇÖs very strong and very pretty.ÔÇØ

Nevertheless, the apocryphal question clung to her. When Tonight Show host Johnny Carson gave Walters his only prime-time interview after announcing his retirement, he brought it up again to tease her, insisted that sheÔÇÖd said it even though Walters told him she hadnÔÇÖt, and added, ÔÇ£What kind of a question is that?ÔÇØ Walters turned the joke back on Carson and asked him what kind of tree he would be. ÔÇ£I might be a tumbleweed,ÔÇØ he said with the grin of a man who had just surprised himself. Both answers, HepburnÔÇÖs and CarsonÔÇÖs, revealed how the speakers wished to be seen, or how they wanted to see themselves.

Biographers spend years trying to glean the kind of insights that WaltersÔÇÖs subjects blurted in response to what mightÔÇÖve seemed like improper, awkwardly phrased, or flat-out weird questions. That was one tool in her kit, a part of her sneaky virtuosity.

Still, she had to convince (mostly male) bosses everywhere she worked that her way was as valid as anyone elseÔÇÖs ÔÇö and that if somebody would say yes to her and let her control the product, Nielsen ratings and next-day media coverage would prove that she knew what she was doing. In 1997, long after Harry Reasoner was dead and buried, The View had to fight for a corporate green light: ABC executives yet again warned Walters that such a program would damage her credibility as a journalist ÔÇö the credibility that her detractors had been saying for decades that she didnÔÇÖt have.

She was permanently unfazed by then and powerful enough to win those fights. Reasoner had undermined Walters so relentlessly at ABC in the ÔÇÖ70s that she left the nightly news broadcast to launch ABCÔÇÖs newsmagazine, 20/20, with her long-ago Today colleague Hugh Downs. Originally a knockoff of 60 Minutes, 20/20 found success by modeling itself on WaltersÔÇÖs interviews: less openly prosecutorial, more businesslike and polite on the surface, sometimes soft, and letting subjects make a case for themselves as human beings before going in with the hard stuff.

Cheri Oteri ÔÇö one of two performers to play Walters as a recurring character on Saturday Night Live ÔÇö summed up WaltersÔÇÖs strategy in an interview with CNN during its 2022 Times Square coverage: She said she once told Walters, who was a fan of her impersonation, ÔÇ£When you do an interview, you usually give three compliments, and then go in for the kill: ÔÇÿYouÔÇÖre a New York Times best-selling author, youÔÇÖre an accomplished and celebrated concert pianist, and a three-time Academy AwardÔÇôwinning actor. Why the porn?ÔÇÖÔÇØ

A formula, perhaps. But it worked. ÔÇ£Does he hit you?ÔÇØ Walters asked Robin Givens during a joint 1988 interview with Mike Tyson, who had married her six months earlier and was sitting next to her. If Walters hadnÔÇÖt opened by inviting Givens and Tyson to assert their mutual love and trust, Givens might not have responded as frankly as she did. ÔÇ£Just very recently IÔÇÖve become afraid, very afraid,ÔÇØ she told Walters and filed for divorce a month later.

A similar thing happened during her interview with Lewinsky, in which she flipped the Oteri formula: list unflattering ways in which others have described the subject, then invite the subject to describe in response.

ÔÇ£Monica,ÔÇØ she said, ÔÇ£you have been described as a stalker, a seductress. Describe yourself.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£I think IÔÇÖm very loving,ÔÇØ Lewinsky replied. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm very loyal. I think IÔÇÖm intelligent. I think I certainly feel that I have been misportrayed in the past year, and unfairly.ÔÇØ

Then Walters asked a question that just happened to sum up why people wanted to talk to Barbara Walters and no one else: ÔÇ£This is the first time that youÔÇÖve been allowed to speak out and say pretty much anything you wanted to say. Is there something that you particularly wanted to say?ÔÇØ Lewinsky apologized to her family for dragging them into the spotlight and to Hillary and Chelsea Clinton ÔÇ£for what happened, and what theyÔÇÖve been through,ÔÇØ a wrenching moment that only Walters could have conjured.

Yet Washington Post TV critic Tom ShalesÔÇÖs next-day column about the interview was typical of the way WaltersÔÇÖs work was treated at every stage of her career. It portrayed her as a scandalmonger feasting on salacious details and trying to get Lewinsky to ÔÇ£make with the Waterworkski,ÔÇØ then grudgingly concluded, ÔÇ£No living human could probably have done a better interview than Walters did, or even nearly as good.ÔÇØ

When Walters started in network news, she was told by her bosses that audiences would not accept a woman as an authority figure unless she was partnered with a man. The final phase of her career was spent on a show filled with women who were listed as her co-anchors, none (officially at least) more important than any other. When she retired from The View in 2014, ABC named its news building after her.