This monthÔÇÖs recommendations will ÔÇö I hope ÔÇö encourage readers to reflect on the legacies of individuals and institutions. An already-classic study on eviction was apparently just a warm-up for a bombshell critical study of poverty in general, and who knew that one of AmericaÔÇÖs most iconic photographers is actually a brilliant filmmaker? Elsewhere, a novelist known for challenging what constitutes literature continues pushing the bounds, and a diligent radio host shows us that there is another way to conduct author interviews.

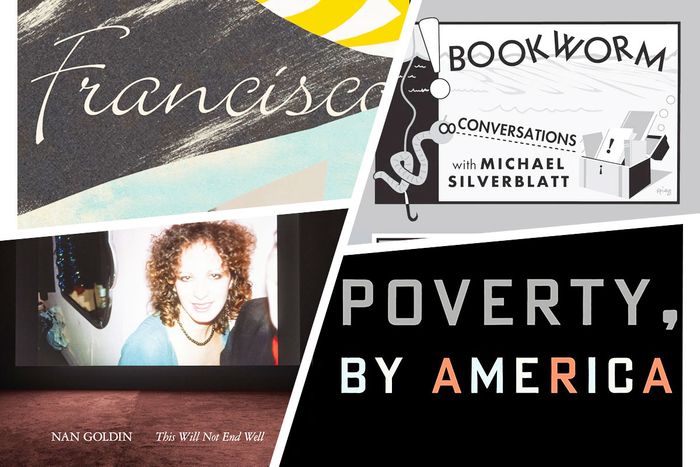

Famed Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond follows up his epoch-defining study of eviction to address poverty more broadly. For starters, everything you think you know about the topic is wrong. ThereÔÇÖs the numbers ÔÇö 18 million families in the U.S. live under the deep-poverty metric of $13,100 ÔÇö and our misguided attempts at thinking outside the box (welfare ÔÇ£reformÔÇØ has culminated in states hoarding and misappropriating block grants, with only $7.1 billion out of $31.6 billion actually going directly to families). But focusing on these statistics obfuscates what is in effect a moral argument. DesmondÔÇÖs great contribution to the topic is asking why we as a society are willing to accept this. His answer ÔÇö that it is in most peopleÔÇÖs economic interest to accept economic arrangements that keep people poor ÔÇö is likely to roil the classic debates about personal responsibility and the like. But be forewarned: His admonishments arenÔÇÖt just lobbied at elites.

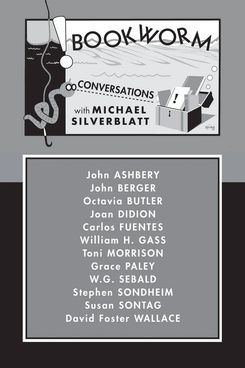

Michael Silverblatt, the longtime on-air book critic for KCRW in Los Angeles, is widely read and deeply thoughtful, and as a result his program, Bookworm, is satisfying to both cultish and well-known tastes alike. Grace Paley, Octavia Butler, and David Foster Wallace are joined by the likes of John Ashbery, Toni Morrison, and Susan Sontag. Neither self-conscious about its influence nor overtly critical in its approach, this collection of author interviews is refreshingly deferential ÔÇö each authorÔÇÖs voice and sensibility commanding the readerÔÇÖs attention. Chronology is irrelevant, but documented ÔÇö in one section itÔÇÖs 1995, and youÔÇÖre listening to William H. Gass explain The Tunnel; in another, Steven Sondheim and John Weidman are chatting it up about Road Show. The anthology cements SilverblattÔÇÖs legacy as a literary steward whoÔÇÖs welcoming and respectful of his listenerÔÇÖs intelligence.

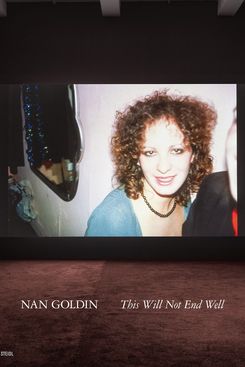

The first exhibition to collect the bulk of the iconic photographerÔÇÖs film work, End Well is a collaboration with Hala Warde and Mark Davis of HW Architecture. The firm designed a ÔÇ£village of slideshowsÔÇØ in Moderna Museet, Stockholm, with each structure designed to best encompass each of Nan GoldinÔÇÖs multimedia works. Even within the confines of the catalogue, the artistÔÇÖs gift at narration and keen eye for unexpected moments is apparent. Readers will likely recognize P.AI.N., GoldinÔÇÖs harrowing protest against the opioid industry, and her breakthrough, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a meditation on intimacy and loss, but less-heralded works, such as Scopophilia and Fire Leap, mesmerize the reader as well. If that doesnÔÇÖt sell it, Goldin also commissioned a Dream Team of commentators on her artistic practice, including Sara Schulman, Lucy Sante, Eileen Myles, Darryl Pinckney, and Patrick Radden Keefe.

Victor LaValles voracious appetite for genre experimentation has taken him to the American West. Dont mind the wagons and tumbleweed: By the time Adelaide, the books narrator, hits the road  fleeing a burning house with her dead parents inside  there are plenty more practical, plot elements to focus on. Theres whether shell make it in Montana as a Black woman  and coming from the mild winters of California, no less. Also, who can she trust there? (Her neighbor Grace? Sure. The Mudges? Ehh ) And then theres the mysterious, heavy trunk that she carries with her on her journey (My whole life  Everything that still matters), which must remain locked at all times. The horrible secret both isnt and is what you think it is, which makes the communitys response to it that much more terrifying.

This brilliant, long out-of-print novel was rescued by (who else?) New Directions. The bookÔÇÖs unnamed narrator, a Black actress tired of being typecast in the same stereotypical roles, is infatuated with the bookÔÇÖs titular character, a noble (but emotionally unavailable) filmmaker. Whether the narrator will invest as much into her own ambitions as she does into her loverÔÇÖs is an open question, but their romp through bohemian California, fully realized right down to the color of a shared pair of trousers, is enough to make the journey worth it. Speakers stop abruptly and pop up in the next paragraph; snappy asides and transitions appear as enjambments ÔÇö pushing the pace forward like the ding of a typewriter carriage. The sensuousness is the point. This latest edition of Francisco gives a new generation of readers the opportunity to think about how little has changed in the culture industryÔÇÖs relationship of convenience with Black artists while riding the waves of NewmanÔÇÖs musical and minimalist syntax.

This look at renowned French publisher Les ├ëditions de Minuit ÔÇö which has worked with Samuel Beckett,┬áAlain Robbe-Grillet, Marguerite Duras, and Jean-Philippe Toussaint, among many others, since its inception in 1941 ÔÇö positions the house as a catalyst for a nationÔÇÖs notoriously self-serious literary culture. Steven D. SpaldingÔÇÖs conceit is that by outlining MinuitÔÇÖs history, he can provide insight into the value judgments placed upon literature within academic and, by extension, popular discourses. Aiming for a meta-literary theory risks backfiring, but SpaldingÔÇÖs work is saved by both the uniqueness of its subjectÔÇÖs origins (it got its start as a clandestine publisher disseminating censored texts during Nazi occupation) and its meticulous accounting of how the pressÔÇÖs New Novel evolved from an avant-garde foil to an expectation of the Establishment.