Every few weeks, Vulture will choose a film to watch with readers as part of our Wednesday Night Movie Club. This week’s selection comes from writer and editor Chris Stanton, who will begin his screening of School of Rock on Wednesday, September 27 at 7 p.m. ET. Head to Vulture’s Twitter to catch the live commentary.

“You’re not hard-core unless you live hard-core” is a mantra that, in my experience, is most fun to invoke in a situation that’s not particularly hard-core at all. It can be muttered while doing the dishes, while resigning yourself to a sad airport sandwich, while popping a few Tums — basically while confronting any of the minor indignities adulthood has to offer. By the time Dewey Finn (Jack Black) sings that phrase a half-hour into School of Rock, it’s clear that, for him, choosing whether or not to live hard-core represents a more severe fork in the road: Either you dedicate your life to the pursuit of face-melting guitar solos at the expense of all else, or you capitulate entirely to the Man and hop on the corporate hamster wheel of death. To paraphrase Ned Schneebly (Mike White), the options are either “satanic sex god” or “working stiff.”

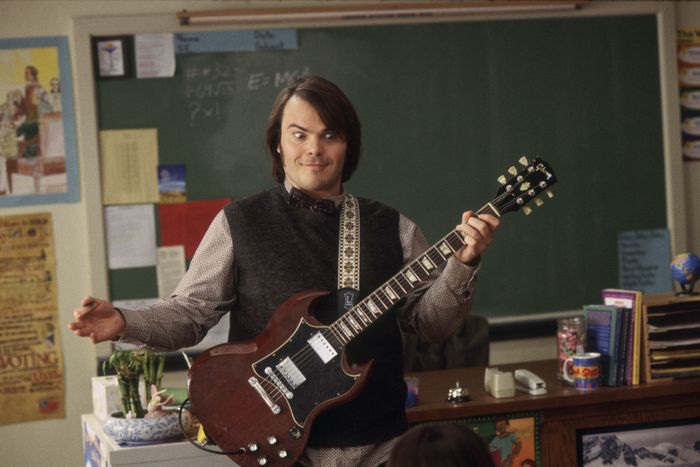

Twenty years after its release, School of Rock stands tall in the pantheon of movies about a group of serious-minded kids who learn the joys of rebellion from a chaotic adult — like a less depressing Dead Poets Society with Led Zeppelin swapped in for Walt Whitman. It follows Dewey, a talented but showboat-y guitarist who gets thrown out of his band, No Vacancy, after taking a stage dive onto a barroom floor. Dewey has spent years crashing with his former bandmate Ned, a pushover who strayed from the divine light of rock and roll to become a substitute teacher. When Ned’s nagging girlfriend (Sarah Silverman, making the most of a questionably written part) insists that Dewey pay his share of the rent, Dewey poses as Ned and takes a substitute-teacher gig at a private elementary school. The uptight students are all classically trained musicians, so Dewey does what any responsible adult would do and forms a rock band with them to compete in the upcoming Battle of the Bands. In the process, he teaches them how to stick it to the Man and they teach him how to grow up a little.

Released in September 2003, the movie was a huge hit with a long cultural tail, eventually spawning a Broadway musical and a Nickelodeon show. (Anecdotally, it also went platinum on playgrounds, with the “read between the lines” gag becoming a subtle-ish way to flip other kids off.) While any movie featuring this banger might’ve been destined for success, School of Rock’s real coup, in hindsight, is how it managed to unite its three principal players — Mike White, Richard Linklater, and Jack Black — at the exact right moment in time to create what remains a high-water mark in each of their careers.

By now, it’s basically a tradition that every new season of White Lotus brings with it TikToks of teens discovering that “Ned Schneebly created White Lotus.” From the beginning of his career, White has admittedly made himself difficult to pigeonhole, working as a staff writer on shows from Dawson’s Creek to Freaks and Geeks while cranking out scripts for movies like the Jennifer Aniston–starring The Good Girl and the himself-starring Chuck & Buck. To hear him tell it, School of Rock came together more easily than his other projects, receiving an instant green light once Black signed on. After being neighbors with Black for a few years, White wrote the film with him in mind, gearing it toward the comedy star’s classic-rock fetish and trying to give him more nuanced material than the frat-guy comedies he was being offered. The result is a script that melds family-friendly goofiness with the pitch-black comedy that White is known for. As with a lot of kids’ movies, the premise here is inherently creepy if you think about it for too long, and White deftly leans into that — think, for instance, of the moment when Dewey tells a room full of disturbed parents that he’s “touched” their kids. Crucially, underneath those jokes is an earnest argument that rock and roll can set you free. “One great rock show can change the world!” as Dewey says. “Do you understand me?”

Few filmmakers could be better-equipped to bring that message to the screen than the guy behind Dazed and Confused. Linklater admits he took some convincing, and might’ve passed on the project if notorious asshole and unfortunately talented producer Scott Rudin hadn’t talked him into it. Thankfully he did, because Linklater proved a perfect fit for the material, maintaining a shaggy comedic tone while hitting the emotional beats with a light touch. Wisely, he held an open casting call for the students, taking time to find kids with musical talents without worrying about their acting experience. A bad child actor will sink a film every time, and it’s to Linklater’s credit that he manages to draw naturalistic performances out of everyone here. Rounding out the cast with the likes of Joan Cusack as the school’s principal (a formative crush for a lot of us — right?), Linklater gives everyone the space to rip a guitar solo or two without losing sight of the ensemble.

Of course, none of that would matter without Black, who’s said that working with Linklater felt like meeting in the middle of their two sensibilities — an indie-film veteran taking a crack at something more mainstream. School of Rock finds Black near the peak of his commercial dominance, just a few years removed from when he literally kicked the door open and announced himself a movie star in High Fidelity, busting out physiologically impossible dance moves while air-guitaring to “Walking on Sunshine.” If, in other movies, he sometimes feels like a wind-up toy that’s liable to start scatting or twirling or doing whatever this is when the director’s not looking, that only makes him more perfect as Dewey, a guy who has to learn how to channel his obnoxiousness into something that’s productive for himself and others.

Somehow, Black’s manic energy creates a perfect three-part harmony with White and Linklater’s sensibilities, an idea best represented by the film’s end-credits sequence. Dewey and Ned have opened up a music school, proving that there is some middle ground between satanic sex god and working stiff. As Dewey and the kids rip through a cover of AC/DC’s “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Want to Rock ‘n’ Roll),” the camera pans around the room, giving everyone a moment to shine while Black conducts the chaos. It’s loose, it’s funny, it’s earnest, and it’s honestly pretty hard-core.

More From This Series

- No Movie Captures the Essence of Neil Young’s Best Songs Like Inherent Vice

- The Action-Goth Masterpiece That Never Got Its Due

- Without Brandon Lee, The Crow Doesn’t Fly