This review was originally published on September 2, 2023. On January 23, 2024, Maestro was nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture.

Carey Mulligan gets first billing in Bradley Cooper’s film about the life of conductor Leonard Bernstein (played by Bradley Cooper). And she deserves it. As Bernstein’s wife Felicia Montealegre, she has to absorb, attract, shield, and parry every loving embrace and slight from her brilliant husband. It’s a reactive performance, and Mulligan plays it with a heartbreaking universality. Yes, she’s doing an accent and “a part,” much like Cooper is. But we connect with her in ways that we don’t with him.

As Bernstein, Cooper’s performance is a masterful reconstruction, but it remains a reconstruction, earthbound and cool to the touch. (As for the much-speculated-upon nose — it doesn’t look to me all that different from Cooper’s own, not-exactly-short proboscis, save for scenes showing him as an old man, where the make-up job is actually quite accomplished.) One senses that the actor has obsessively studied every TV appearance, every inch of documentary footage, to recreate Bernstein’s diction and manner, his haughty and rapid-fire way of speaking. Maybe that’s the problem. It feels throughout like we’re watching a TV interview with Bernstein, like he knows the camera is on him. There are almost no unguarded, intimate moments. Or rather, there are no unguarded, intimate moments that don’t feel like guarded, public moments.

The problem, and maybe also the point: The film opens on an aged Bernstein, years after Felicia’s death, being interviewed for television, and the cameras do always seem to be on him throughout the movie. This is, after all, a conductor who achieved stratospheric fame partly thanks to his public image, and the way that he used the medium of TV to broaden the appeal of classical music for young viewers and average Americans. The film suggests, intentionally or not, that the performance never ended for Bernstein, that he was always playing a part.

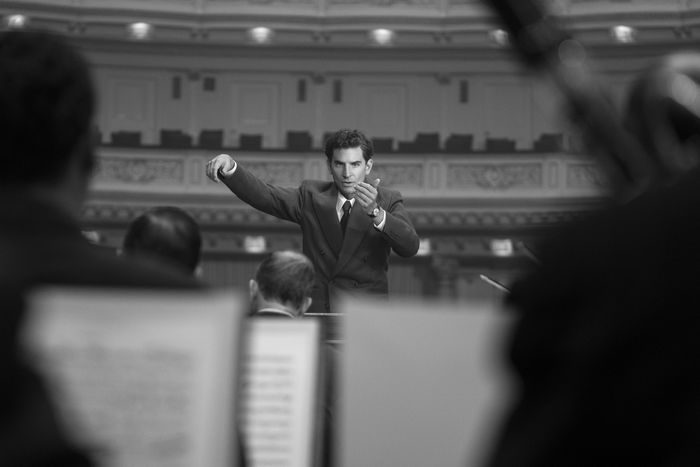

Maestro somehow proves that Cooper is a director of genuine vision, even though it’s not a particularly successful movie. He recreates with epic aplomb the legendary November 14, 1943 phone call a young Bernstein, then an assistant conductor for the New York Philharmonic, received asking him to fill in at the last minute for flu-ridden guest Bruno Walter, for a Carnegie Hall concert that would be broadcast live on the radio. A massive curtain, light filtering around its edges, dominates the screen as Lenny receives the phone call that will change his life and the course of classical music in the United States. When he triumphantly opens the curtain to let an explosion of light fill the room, we see that he’s in bed next to a man, David Oppenheim (Matt Bomer), who was Bernstein’s lover for some years before he met Felicia. Then, the camera tracks with Bernstein as the set opens onto the orchestra, in a delirious shot that ably evokes the dizzying nature of his sudden rise to celebrity.

Maestro is not a particularly long or dense picture. Cooper has reportedly bristled at descriptions of it as a “biopic,” and it’s not hard to see why. The film doesn’t pretend to be a complete look at Bernstein, and there are many aspects of both his life and career that go largely unmentioned. The focus here is on his marriage to Felicia, his homosexuality, and his conducting, all of which are emotionally intertwined. Felicia seems to understand Lenny even better than he understands himself. (“I know exactly who you are,” she says early on. “Let’s give it a whirl.”) He certainly loves her, and there’s fine chemistry between Cooper and Mulligan. In his conducting, however — in those frenzied, explosive public performances that Cooper, again, recreates wonderfully — we sense an inner restlessness, a man yearning to break out of his skin and his persona to find himself.

That’s a beautiful, moving idea, but the movie feels emotionally stunted, perhaps because this construction is based on the idea of stamping down, of denial. It’s also probably why Mulligan nearly acts Cooper off the screen: Her Felicia seems to know exactly who she is, and our heart breaks for her, while Lenny is a restless dynamo, impossible to pin down, a man who never self-actualized. There is a lovely moment near the end, in which Bernstein, now an old man, dances with his students during a party at Tanglewood, and we get a brief glimpse of unguarded freedom. But it remains a glimpse. In that sense, maybe the film lives up to its opening lines, something the real Bernstein did say: “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” If Maestro remains frustratingly unresolved, maybe that’s because it has to be.

More From Venice

- Agnieszka Holland’s Green Border Is an Urgent Warning

- Ava DuVernay’s Origin Devastates Its Audience

- If Glen Powell’s Not Already a Star, This Movie Will Make Him One