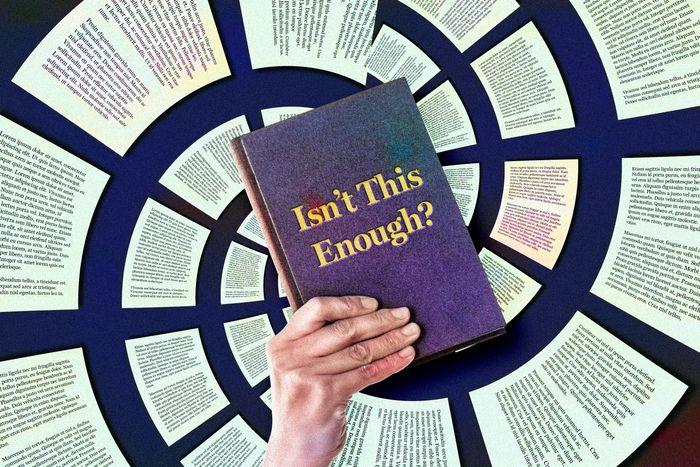

In the months leading up to the April 2022 hardcover release of my book, Some of My Best Friends, I tended dutifully to the rituals of prepublication. I sent a gamely cheerful email blast to my contacts asking them to please preorder copies. I plastered my website and social feeds with graphics of the cover art. I retweeted, with genuine glee, every photo of a galley copy spotted in the wild. I was going to be a model citizen of self-promotion, giving my debut a fighting shot at selling well.

But there was one directive from my publishing team that brought me up short: to brainstorm essays related to themes in my book, ideally keyed to the news, which could then be pitched to various outlets to coincide with publication. I took the instruction as I had all the others ÔÇö if it helped the book, then of course I would do it. But after losing several Sundays to a blank document, I realized that mining for soundbites felt deeply at odds with the work I wanted to put into the world. IÔÇÖve seen fellow writers nail this task, and I admire my peers who seem to have a knack for it. But of the many challenges involved in producing and marketing a book, the one I find most intractable is the idea that writing promotional essays is always an effective way to support your book.

I understand how weÔÇÖve arrived at this point. In principle, the idea makes sense: If a writer has just churned out tens of thousands of words on a subject, surely they can cough up a few thousand more in order to reach a broad audience, establish authority, and sprinkle a trail that leads readers straight to the preorder button. Recent examples from the New York Times opinion section ÔÇö perhaps the grail for promo essays ÔÇö include an essay on BidenÔÇÖs cognitive abilities, by the author of a forthcoming book on memory, and ÔÇ£My Father, Ronald Reagan, Would Weep for AmericaÔÇØ (Patti Davis, who just published a book about her parents called Dear Mom and Dad), both of which offer a preview and a primer on the issues their books explore.

But in practice, such essays can make for a tricky genre, which embodies an expectation that shapes other parts of the promo process, from interviews to personal branding: that writers be ambassadors or educators for their booksÔÇÖ issues, even if those issues are incidental to the work. Reducing something to its buzziest takeaways is part of selling anything, and for subject-matter experts writing on topical issues, this distillation is more straightforward. But for a sizable cross-section of others ÔÇö including essayists, memoirists, and fiction writers ÔÇö the role of ambassador is an awkward fit.

Rainesford Stauffer is the author of An Ordinary Age and, more recently, All the Gold Stars. In promoting the former, a book on the cultural pressures that shape young adulthood, she was thrust into the role of ÔÇ£spokesperson on all things millennial.ÔÇØ As she explained to me, ÔÇ£Because millennial has become such a headline-y buzzword, it felt like everything could be spun through [that] angle.ÔÇØ Editors wanted her to pen essays with a generation-wars slant. Interviewers asked her why millennials are so slow to grow up. She hadnÔÇÖt anticipated this pressure to be an ÔÇ£Author with a capital A,ÔÇØ performing total confidence in anything vaguely related to her book ÔÇö a reported look at how milestones such as college and internships have become so prized that theyÔÇÖve turned young adulthood into a ÔÇ£competitive sport.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£For a long time, I felt like I was letting everyone down,ÔÇØ she added. ÔÇ£I couldnÔÇÖt get to that place where I was ready to step up and say, ÔÇÿI am an authority on everything in [my book], from perfectionism, to work and burnout, to unpaid internships,ÔÇÖ when I am not any of these things.ÔÇØ

Lilly Dancyger, author of the forthcoming essay collection First Love, faced similar expectations while promoting her 2021 memoir Negative Space. The memoir centers on DancygerÔÇÖs childhood and the impact of her parentsÔÇÖ struggles with heroin addiction. But while doing press, interviewers would pose policy questions. ÔÇ£There was this assumption that because addiction was part of the story I was writing,ÔÇØ she said, ÔÇ£I should have deeply held and informed opinions about how society should handle addiction [and] treatment.ÔÇØ When planning the essays sheÔÇÖd pitch, Dancyger considered trying for a big, timely op-ed. ÔÇ£If I really wanted to get into some of the top-tier general interest publications, a topical, opinionated piece on that subject probably would have been the way to go.ÔÇØ But she ultimately decided that being a commentator wouldÔÇÖve felt disingenuous and ÔÇö more importantly ÔÇö was irrelevant to the book. Her priority was to give people a sense of who she was and what she cared about as a writer, which in turn provided a better glimpse of what her memoir had to offer.

Predictably, your risk of being cast as spokesperson increases if youÔÇÖre writing on a subject (or from a perspective) that the publishing industry hasnÔÇÖt previously given much space. Angela Chen, author of Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex, knew that sheÔÇÖd become an ambassador when her book came out. ÔÇ£There just arenÔÇÖt that many trade books about asexuality, which means thereÔÇÖs more scrutiny and more pressure,ÔÇØ she said. Though Chen is a subject-matter expert, she notes that she ÔÇ£didnÔÇÖt want to be only talking to an audience as an educator. I wanted to be talking to the people who are affected and to my own community.ÔÇØ

I felt a similar expectation to educate. My book is an essay collection about how institutions have learned to parrot the language of social justice even (or especially) when it isnÔÇÖt sincere. That meant the news pegs on which I could hang my hat on were grim: public failures of diversity. Literary figures who were ripe for cancellation. The proverbial ÔÇ£racial divide,ÔÇØ a phrase that makes me think of nothing other than, reliably and inexplicably, an image of the Grand Canyon. I wanted to do whatever I could for my book, and I knew tackling these issues could be a shortcut to grabbing thousands of readers by the collar and teaching them my name.

But they were also subjects I found intellectually dull, creatively deadening, and artistically demoralizing. Again, I get the principle, even respect its mercenary logic: If I could make myself a mouthpiece for the biggest issues tangentially related to my book, people would be more likely to care. If I proved myself nimble enough to chase the ambulance, they would know to call my number. The problem was that none of these ideas felt faithful to the work IÔÇÖd done or the kind of thinker I am ÔÇö and I was horrified by the implication that they might be. If you stripped everything else away ÔÇö the research, the jokes, the painstaking revision ÔÇö was this really what my creative labor boiled down to? That we should cancel Joan Didion?

None of this is to say that the promotional essay is all schlock and mirrors. An essay can be deeply aligned with the concerns of a writerÔÇÖs book, get published around the same time, and still be searing: Nicole Chung on the untenable financial costs of choosing the writing life; Zadie Smith on thinking sheÔÇÖd never write a historical novel; Stauffer on the perils of our ambition narratives. The writers I spoke to for this piece all developed ways to approach the task that felt authentic. Before his novel Appleseed came out, Matt Bell sent a list of essay ideas to his editors to make sure he was pitching things he felt both keen and equipped to address, like his bookÔÇÖs genre-fiction elements. ÔÇ£As much as possible, I wanted to be proactive in what that part of the pitch would look like,ÔÇØ he said, rather than letting others decide for him.

Setting limits can help ensure that a writer isnÔÇÖt pushed into mining their work in uncomfortable ways. Taylor Harris, whose memoir This Boy We Made explores medical racism, disability, and genetics, published one essay about being a BRCA2-mutation carrier and then gave herself permission to step back. ÔÇ£After that piece ran,ÔÇØ she said, ÔÇ£I just had to remind myself that I donÔÇÖt have to take on every opportunity related to breast cancer or genetic mutations.ÔÇØ

The balance is one IÔÇÖm still figuring out. I know there are prospective buyers who long for an intrepid expert to lead them out into the racial divide ÔÇö and I know I risk sounding precious when I try to describe why this isnÔÇÖt the book I wrote, or how I want to sell the one I did. ThereÔÇÖs so much creative potential in writers returning to the subjects of their books to drill down or build on their themes. But so much can get lost when the sole approach is to find the snappiest topical takeaway in a clear grab for attention.

Besides, how much difference does a media hit like this really make to a bookÔÇÖs fate? ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs my sneaking suspicion that it does very little,ÔÇØ Bell said. Katie Gutierrez, author of the novel More Than YouÔÇÖll Ever Know, also went into the process with eyes open, as published friends had advised her thereÔÇÖs not much an author can do to move the dial on sales. (That sound you just heard was a thousand publicists screaming.) Like Bell, Gutierrez was proactive about the essay-writing process, but recognizes that a titleÔÇÖs ultimate success is determined by other factors. ÔÇ£It depends on how much support youÔÇÖre getting from the publisher versus how much youÔÇÖre expected to do yourself,ÔÇØ she added. For someone with a slimmer marketing budget or less institutional backing, there may be more pressure to land that op-ed. Or, as the release of their paperback nears, to write the sort of essay they were meant to be writing when their book originally came out ÔÇö even if that essay is a rebuttal of this whole exercise.