In the early years of his life as an actor, Anthony Boyle made the strategic decision not to play what he called the “Belfast lad” — the kind of rough-and-tumble Northern Irish guy, fond of a pint and a good yarn and not to be crossed, familiar in a lot of media from the British Isles and perhaps not too dissimilar from Boyle himself. He grew up in West Belfast, dropped out of school at 16, and worked a series of odd jobs — including bartending and performing on ghost tours — before going to drama school in Wales. He had a breakout moment playing the very posh, very blond son of Draco Malfoy in the play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, first in London (where he won an Olivier Award), then on Broadway. He pursued a slate of American roles on American television: as one of the troupe of young fighter pilots in this year’s Masters of the Air and as John Wilkes Booth in Manhunt (both on Apple TV+, the preferred streaming service of people who have probably done walking tours of Gettysburg). But as Boyle approached 30 — his birthday was in June — he tells me, “I was like, I want to go home. I want to do Irish roles.”

Boyle has come home in one of the more dramatic ways possible: In the FX series Say Nothing, he plays Brendan Hughes, an officer in the Provisional Irish Republican Army nicknamed “the Dark” and something of a folk hero in Northern Ireland. A mural of Hughes, Boyle tells me, graced a wall along the Falls Road near where he went to school and where his father still works security. The series, like the book by Patrick Radden Keefe on which it’s based, focuses in part on the life of Dolours Price (Lola Petticrew), who became active in the IRA as a teenager. Dolours and her sister Marian were central figures in two car bombings in London in 1973. They were imprisoned and force-fed in British prisons after going on hunger strike and, later in life, became disillusioned with the peace process. The show’s version of Hughes, as played by Boyle, comes into Dolours’s life as a charismatic radical comrade in the fight for a united Ireland. Playing a character like Hughes felt viscerally familiar to him, he says. Unlike most other roles, he didn’t have to master a new accent or do intensive historical research. He’s been to the same pubs Hughes himself frequented.

The Pluck of the Irish

In person, Boyle has that similar rambunctious and infectious humor that makes his version of Hughes so charming. He arrives late to our morning interview at a restaurant just south of Central Park. His tardiness, FX’s PR rep tells me, is due to a snag with arranged cars, but I get the sense it may have also been because he’d spent a good amount of the night before partying after the American premiere of the series. “I brought the cast to Flaming Saddles,” he confides in me, the Wild West–themed midtown gay bar, clearly delighting in the image of his colleagues surrounded by guys in hot pants.

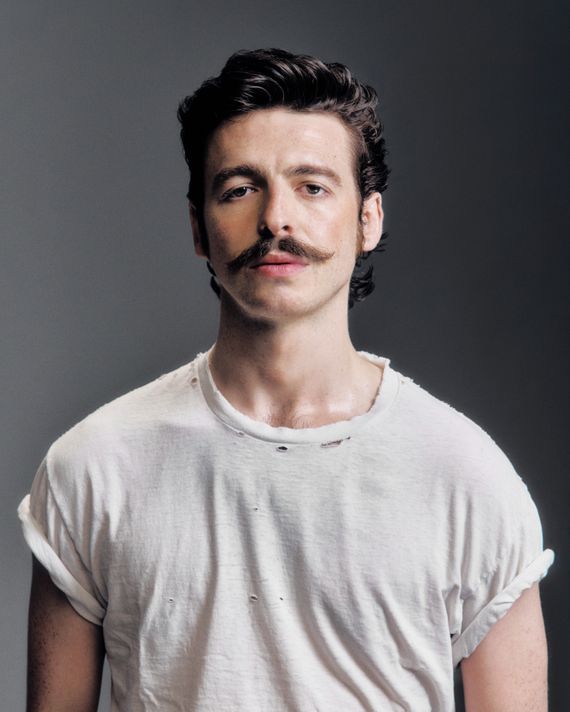

Boyle is lightly frazzled by jet lag: He’s flown to New York in the midst of night shoots for another Irish project, Steven Knight’s film House of Guinness, in which he plays Arthur Guinness, an heir to the beer fortune. (Arthur supported British rule of Ireland, Boyle points out, so he can play both sides of the aisle.) The current state of his ’stache, more tweezed than Hughes’s rebellious bushy caterpillar, is owed to that role. After rocking a mustache in Manhunt, Boyle wonders whether his calling card lies above his upper lip. He tells me, “My agent said to me last night, ‘Next role we’re doing, you can’t have a mustache.’”

He got Say Nothing through his friend and co-star Petticrew, also a Belfast native, with whom Boyle appeared in what he describes as a “terrible” chess-themed production of Romeo and Juliet as a teenager. “I watched a scene last night where Lola says something to me and I go, ‘You’re a cheeky wee bitch,’” Boyle recalls. “That wasn’t in the script, but that’s just how we are with each other.” One of Say Nothing’s directors, Michael Lennox, had worked with Boyle and Petticrew on a microbudget short film made before Boyle went to drama school. “I was promised 100 quid, and they didn’t pay me,” Boyle says. “I got this role, so it paid off, but — put this in the interview — I still want that 100 quid!”

The history Say Nothing covers is fraught, and Boyle initially expressed concerns that “two American lads,” Keefe and the show’s creator, Josh Zetumer, would try to find a simple narrative in a story about the Troubles. “I said to them, ‘I’d love to do this, but I don’t think we should try to define what “this” is. This is a messy, checkered history,’” Boyle says. “It will work if you just ask questions and connect to the humanity of it.” His fears, he adds, were assuaged in reading Keefe’s book — the work of “an amazing journalist and an incredible writer” — and in the way that Zetumer’s script captured what Boyle found to be a distinctly Northern Irish sense of humor. “With a lot of people who have been displaced, they end up very funny because there’s so much trauma,” Boyle says. “If you never got a pot to piss in, it helps to be able to laugh.”

Boyle grew up in a Catholic family. His father likes to tell a story about a gun battle between the Brits and the IRA happening in the street one day when his mother told him to go and pick up some milk and eggs. Boyle delivers the punch line with precision, cracking himself up in the process: “He goes, ‘But Mommy, they’re shooting outside.’ She said, ‘They’re hardly fucking shooting at you.’”

As much of a jokester as Boyle can be, he understands the pain underneath those jokes as well as Say Nothing’s political weight — the tightrope it walks in its depiction of the IRA. In the fourth episode, which hangs on Boyle’s performance, Hughes is pressured to accept the execution of informants to whom he’d previously offered mercy if they double-crossed the Brits. “During wartime, people do awful, horrible things,” says Boyle. “I still don’t know what I think about it. I put my heart into it.”

The show skips across the decades, dramatizing the interviews an older Dolours (Maxine Peake) did for a Boston College oral history of the Troubles, which were taped with the promise that they would be released only after participants’ deaths. On the tapes, she disavows the IRA’s methods and direction. Hughes (Tom Vaughan-Lawlor plays the older version) also participated in the project before his death in 2008. In the show, he’s seen expressing similar doubts to Dolours’s, especially about the actions of politician and former Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams, whom Say Nothing depicts as the ruthless head of the IRA (as the FX series notes at the end of every episode, Adams himself has always denied involvement with the IRA).

Boyle is bracing to hear what the crowd back home thinks of the show. He has secured one endorsement of the series from his own parents. He FaceTimed them when he got to the Say Nothing set — a re-creation of the streets of West Belfast on soundstages outside London — and it brought the past back vividly. “For me, I was just on a movie set,” he says. “For them, they were like, ‘This was our life.’” A few weeks before our interview, Boyle showed them the finished version of the series. “My mom, one of her earliest memories is the Brits raiding the house and her father getting pulled down the stairs by the British Army,” Boyle says. When a similar scene plays out in Say Nothing, they had to pause the show because she was so shaken by watching it. “It made me feel perversely good, in a way, because we’d done it right,” Boyle says. “Hopefully the people in West Belfast watching this will connect with it if they’ve had similar experiences. They’re the audience I give a fuck about.”