When was the moment Ireland became cool? Was it in December 2018, when Derry Girls hit Netflix, introducing a global audience to Northern Ireland’s ’90s pop-culture ephemera? Or was it a few months later, when Sally Rooney’s Normal People arrived in the U.S., occasioning multiple glowing New York Times reviews and spurring the first wave of trend pieces about “the cult of Sally Rooney”? Either way, by the time The Banshees of Inisherin was released in 2022, a full-on Irish cultural invasion was underway. Call them the Craic Pack: Authors such as Anna Burns and Paul Lynch won major prizes. Actors Colin Farrell and Cillian Murphy and singer-songwriter Hozier stepped back into the spotlight. Barry Keoghan went from art-film weirdo to pop-star boyfriend. Even brands got swept up in it: You couldn’t call yourself an Instagram baker without extolling the virtues of Kerrygold butter.

As with Taylor Lautner in the second Twilight movie, our affable friend across the pond turned out to be hiding eight-pack abs. “Over the past few years, it’s become quite twee and also quite sexy to be Irish,” says the writer Róisín Lanigan, who published an essay in Vice on the subject. Lanigan first noticed a change around the time Normal People debuted on TV and made a star of Paul Mescal. “Americans and English people were introduced to a new vision of Ireland: rose-tinted and beautiful,” she says. Lanigan comes from Northern Ireland, and she cautions that this new vision usually depicts “a certain type of Irish. On the whole, it seems to be, ‘They’re hot and sad.’”

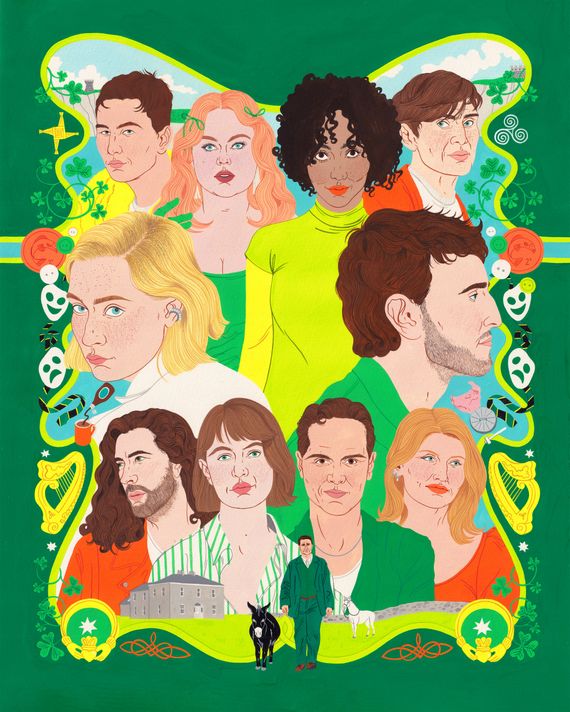

The Pluck of the Irish

The Pluck of the Irish

Accurate or not, Americans liked what they saw. This past summer’s craze for “hot rodent boyfriends” spotlighted several Irish actors. An Instagram account that does nothing but post photos of Mescal has over 160,000 followers. On YouTube, an interview in which comedian Brittany Broski joked that her greatest career goal was “Irish cock” received 2.7 million views.

Among young, online, lefty Americans, the Irish are considered “the good Europeans.” While cinephiles shudder to learn the opinions of their favorite French actors, Irish stars are assumed to have respectable politics by default. A nation that lagged behind its neighbors economically and politically now appears startlingly progressive: A former colleague once told me, approvingly, that the Irish were the only anti-colonialist white people he had ever met.

It hasn’t always been like this. While Ireland has always punched above its weight culturally, the shine of its many luminaries rarely reflected back on the island. (Few people finish reading Dubliners wishing they were a Dubliner.) When I call up columnist Séamas O’Reilly to discuss the shift in Ireland’s reputation, he paraphrases a famous quote from the author Iris Murdoch: “Being Irish is a bit like being a woman: Everyone says you’re perfectly nice, but you get the feeling you’re not very important.” To O’Reilly, Ireland benefits from being “everyone’s second-favorite country. There’s a nonthreatening feeling to Ireland. We’ve never invaded anyone; we’ve never colonized anyone. What’s not to like about that?”

Still, he finds it funny that Irishness is now “cool.” According to O’Reilly, “Irish people are cool in a completely different way than things usually get called cool. When I think of the things I like about Irish culture, it’s the interpersonal things. It’s based on humor. It’s extremely friendly — there’s a neighborliness.” He points to his father, whose father was a farmer from Fermanagh who came from a long line of farmers from Fermanagh: “There’s a small-village mentality. Culturally, you shouldn’t make a show of yourself.” The current crop of Irish talent exemplifies these qualities, O’Reilly says. “You see Paul Mescal, Saoirse Ronan, Colin Farrell, or Brendan Gleeson being so down-to-earth when they talk. It seems like a superpower that they’re normal people.” (Pun not intended.) These Irish stars haven’t yet been hit by the homegrown backlash someone like Bono attracts. “It’s nice that we like our brand ambassadors,” O’Reilly says.

Ask those who work in the Irish cultural scene about the explosion of interest in Ireland and they will likely point you toward an increase in arts funding, new tax credits for filming, and a history of emigration that allows Irish artists a transnational point of view. History too is responsible for Ireland’s current progressive image. The fact that the Catholic Church held so much sway over the Republic of Ireland’s political institutions for so long ensured that, once the shackles were loosened, the South more or less speedran the entire postwar era in the past 30 years. Same-sex intercourse was decriminalized in 1993; divorce was legalized in 1996, followed by same-sex marriage in 2015 and abortion in 2018. Thus, as the U.S. and U.K. have too often in the past decade seemed to be moving backward, it is Ireland that appears striding confidently forward.

If Ireland has evolved to meet the wider progressive community where it’s at, so too have young progressives begun to follow the Irish lead. I first noticed this after the death of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, when Irish Twitter set the tone for the subsequent online jubilation. On Twitter, a video of Irish soccer fans chanting “Lizzy’s in a box” received over 133,000 likes. A TikTok clip of Irish step-dancers performing a rendition of “Another One Bites the Dust” outside Buckingham Palace was viewed more than 6 million times, its power undimmed by the unfortunate detail of having been shot while the queen was still alive. That week, I was struck by how many of my friends all of a sudden became stalwart anti-Royalists. To me, it felt a bit like a leftist St. Paddy’s Day — weren’t they appropriating the political bona fides of the Irish, who had come by their hatred of the royals the hard way? When I mention this to Lanigan, she demurs. “I don’t think you have to be Irish to be anti-Royalist,” she says. “You just have to be sensible.”

This reputation for plainspoken wisdom and anti-imperialist cred explains much of Irishness’s contemporary appeal. As Sharon Horgan, who returned home to make Bad Sisters after years working in British TV, told The Independent in 2021, “We’re naturally quite pleased with ourselves but also historically shat upon. I suppose Ireland is the natural underdog, in many ways. And we’re very good at telling the truth.”

To Americans sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, the image of the Irish speaking truth to power has only intensified since the beginning of Israel’s war in Gaza. In keeping with the historic solidarity between Irish republicans and the Palestinian people, Irish celebrities have been particularly vocal in the antiwar effort. Rooney used the launch of her book Intermezzo to speak out against the “unfolding genocide.” Mescal donated a signed Aftersun poster to the Cinema for Gaza auction. Nicola Coughlan, whose father served as a U.N. peacekeeper in Jerusalem, spent her Bridgerton press tour wearing a cease-fire pin and has since called for an arms embargo. Barely a day goes by without an Irish-memes account reposting an old photo of Farrell in a keffiyeh. Fandom being what it is, even pro-Palestinian activism can take on a competitive edge: I’ve read blind items hinting that Rooney had urged an unnamed Irish celebrity to be more outspoken on Gaza.

For Northern Irish Catholics, who have their own cultural memory of armored cars and tanks and guns, the parallels are starker still. Onstage at the Reading Festival over the summer, the Irish-language hip-hop group Kneecap drew a line between the violence of the Troubles and the harm inflicted upon the people of Gaza. Two-thirds of the group are from Belfast, which member Móglaí Bap described to the audience as “still under British occupation.” But, he told the crowd, “there’s a worse occupation happening right now in Palestine. They’re bombing Palestinians from the sky.”

Around this time, Kneecap’s self-titled biopic was a hit in the U.K. and Ireland; it has since been selected as Ireland’s official Oscar submission. The film features a cameo from Gerry Adams, former Sinn Féin leader (and long-rumored former head of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, which he denies). A man once considered too dangerous to be heard on television participates in a gag about drug-induced hallucinations. That neatly sums up the journey taken by Northern Ireland in the 26 years since the Good Friday Agreement. While the Republic still dominates Ireland’s international image, projects like Derry Girls have helped the North catch up. “We were a bit of an awkward subject culturally, and now it’s less awkward,” says Lanigan, who notes that, for the first time since the 1970s, movies and TV shows set in Northern Ireland no longer need to open with a montage of sectarian strife. The movie Kneecap takes the piss out of this trope, as it does basically everything else about the Troubles. If there is a knock on Kneecap, it’s that they’re messing about with the imagery of a conflict they’re too young to have experienced. But as the group’s Mo Chara puts it to me, “What else are we gonna do — stay traumatized and miserable?”

We should not forget that the new Irish fantasy leaves out just as much as the old one did. Just as modern Ireland is not a romantic backwater, so too is it far from a socialist paradise. Since the Good Friday Agreement, Northern Ireland’s devolved legislature has spent much of its history unable to function. The Republic is ruled by the nigh-indistinguishable centrist parties Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. (Although if you like tax breaks for American tech companies, have I got a nation-state for you.)

And Ireland is not immune from the maladies that have afflicted the U.S. and Britain. It has a housing crisis too, as well as a growing threat from the far right, which was behind a series of anti-immigration demonstrations this past summer. Lanigan finds the way Irishness has turned into a meme a modern form of paddywhackery, the ancient habit of “playing up the cutesiness that makes other parts of Irish identity more palatable.” (Incidentally, this is the issue many Irish critics have with the work of Martin McDonagh, who was born and raised in London.) Like many Irish before her, Lanigan emigrated for better opportunities in England. “The Irish diaspora thrives when conditions of late capitalism make it seem that you can’t live at home,” she says. “But the nature of modern immigration means that people are now coming to Ireland. I don’t think there’s a cultural reckoning with what that means. There’s an awful lot of racism around ‘What does it mean to be Irish? Can you be Irish if you’re not white?’”

O’Reilly doesn’t want to comfort himself with the notion that Ireland’s experience of subjugation has inoculated it against the xenophobia on the rise elsewhere in Europe: “What kind of arrogance do we have to imagine that we somehow have the emotional or intellectual infrastructure to be able to forestall this?” Yet he can’t help but take solace in examples of the Irish pushing back on nativist myths. After our interview, he sends me a clip of a woman in Dublin firmly shooting down a right-wing -YouTuber trying to bait her into a confrontation over migrants. Before the potato famine, she notes, Ireland had 8 million people — millions more than it does now. There’s more than enough room.

Any time an identity becomes a trend, there is an inevitable sense of dislocation. “When I first started writing fiction years ago, a publisher said to me, like, ‘We’ve got enough Irish stories at the moment,’” Lanigan says. “That seemed to change in the past couple of years. You had articles about ‘the Year of the Irish,’ and it was boxing-in in a different way.” Irishness is currently having a moment. But then what? “Maybe it’s just in vogue,” O’Reilly says. “In three years’ time, everyone will be going for whatever Venezuela’s prevailing social mores are.”