From the outside, meditation seems like the simplest of tasks: sit silently and focus on your breath as it moves in and out of your body so as to be completely in the present. Easy peasy, right?

But anyone who has attempted meditation, either laying in bed, sitting in a chair or in full lotus position, will tell you it’s not that simple. Even the most eager yogi can sit, take a deep breath, find themselves relaxing and congratulate themselves on how well meditation is going. But then, maybe you focus on your breath and immediately Faith Hill’s “Breathe” plays back in your mind (or else Fabolous’s “Breathe”). Regardless, you will soon find yourself face to face with what many teachers and practitioners refer to as “monkey mind.” Leaping, playing, spinning, making lists of chores to finish and emails to fire off, phone calls that need to be made, that “monkey mind” makes us realize that calming the modern mind is not a simple task, but in fact a Herculean one.

“Musick has Charms to sooth a savage Breast,” so goes the oft-misquoted line from playwright William Congreve, but music also has the ability to calm the monkey mind and allow a greater sense of calm to come to its listeners. With the surge in interest in Eastern philosophy and meditation in the West beginning in the 1960s, music was often used to transport its audience into heightened states of awareness. Jazz musicians like John and Alice Coltrane sought to infuse Eastern sensibilities to Western music to achieve a universal sound, which often included sitar and tambura in a jazz setting. They weren’t alone: Musicians like Tony Scott and Paul Horn began to travel with their horns through the East, bringing such sensibilities back with them.

And when Brian Eno began releasing a series of albums in the mid-’70s under the banner of “ambient,” a new sound world emanated from turntables in living rooms everywhere. With albums like 1975’s Discreet Music and 1978’s Music for Airports, Eno introduced a way of perceiving — or not perceiving — sound that was equally valid. As he wrote on the back of Music for Airports, his intent with the music was to “accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.”

That ability to both tune in and drop out to a sound led to a cottage industry of meditation music catering to relaxation, stress relief, lucid dreaming, chakra auditing, yoga, and meditation. Dating back to the late ’60s, New Age music arose thanks to the sonic questing of composers and musicians like Iasos, Paul Horn, Steven Halpern and Irv Teibel and his influential Environments series. “Music and meditation are two aspects of the same phenomenon,” wrote Indian mystic and guru Osho. “Without music, meditation lacks something; without music, meditation is a little dull, unalive.”

To our ears, dull meditation music is not all that enlightening either, even if it’s functional when playing at the spa or at your next Bikram yoga class. And so, here are a few albums to cue up and enliven your next meditation attempt. Some are serene, some hushed, some with washes of noise and drone at their root. Some come from 40 years ago, some from the new century. Pay attention or tune them out as you will. Set them at the lowest volume on your Sonos or crank them up in your earbuds. As British-born Zen philosopher Alan Watts once esteemed: “If you can’t meditate in a boiler room, you can’t meditate.”

Tony Scott, Music for Yoga Meditation (1972)

Throughout the 1950s, Tony Scott contributed his cool style of clarinet for the finest ladies in jazz, such as Sarah Vaughn, Chris Connor, and Billie Holiday. But at the end of the decade, bebop took over and his gigs dried up. So Scott split from America and traveled through Southeast Asia, ultimately winding up in Japan, playing in a Hindu temple and getting hip to Lord Krishna. Upon his return in the mid-’60s, he released Music for Zen Meditation and Other Joys, his clarinet playing moving slow as a mountain stream. It’s an important precursor to the rise of New Age music, but Music for Yoga Meditation is the one to reach for, as Scott’s clarinet moves with sitar across ten tracks that trace the rise of Kundalini energy through the chakras.

Charlemagne Palestine, Strumming Music (1974)

Charlemagne Palestine is the enfant terrible of New York minimalism in the 1970s, in the lineage of composers like La Monte Young and Terry Riley, but riding on his own wavelength. Born and bred in Brooklyn, Palestine sang in synagogue and wound up as carillonneur at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Manhattan, ringing bells every day and playing with their massive overtones for passersby. Palestine also began making noise on the gallery scene, with punk-like performances wherein he smashed himself against gallery walls or else did piano performances in a cognac-fueled trance surrounded by teddy bears. Which makes the steadfast, almost maniacal buildup of overtones on his first album, Strumming Music, feel all the more profound. Deeply focused and attuned to the play of overlapping drones that arise from the hammered piano keys, Palestine creates a sustained sound that is transportive.

Steve Hillage, Rainbow Dome Music (1979)

British guitarist Steve Hillage is a legend in prog-rock circles, bending strings and minds as member of bands like Gong, Khan, Kevin Ayers, and, bizarrely, alongside the likes of snotty punks Sham 69. In 1979, he was asked to create an ambient atmosphere in London for the 3rd Festival for Mind Body Spirit, a gathering of the tribes for folks interested in astrology, UFOs, Earth mysteries, yoga, dance, natural living, and more. Hillage obliged with a blissed-out soundtrack piped into a “rainbow dome,” creating this 43-minute opus full of treated guitars, twinkling ARPs, gurgling water sounds, and Tibetan bells. In the age of punk, it may have been seen as a hippie soundtrack, but by the end of the ’80s, it became a staple of chill-out rooms. Hillage soon found himself back at the fore of adventurous electronic music, collaborating with merry pranksters The Orb and System 7.

Craig Kupka, Clouds (1981)

Not much is known about Craig Kupka, though he now serves as a faculty member at California State University and — as one comment on the record-nerd-heavy Waxidermy message board proclaimed — “wow, this guy was my high school jazz band instructor.” Before he was on RateMyProfessor.com, Kupka released a series of records in the late ’70s meant to serve as “modern dance technique environments,” and at the turn of the decade, he released two ethereal albums on the Folkways label, putting his music in libraries around the country. “Clouds was designed for classes in relaxation, meditation, quiet times in elementary schools, homes or office, as a non-eastern musical alternative for Yoga,” the liner notes attest on his stunning drift of cumulous chords. “[It] … can be used in Dance Therapy & Modern Dance Classes, anywhere that quiet non-rhythmic music is desired.” Utilizing bells, vibraphone, bass guitar, synthesizers, and wind chimes, Kupka created a beatific, slow-moving suite, perfect for watching its subject matter float across the sky, or for letting your mind let go of all its temporal concerns.

Brian Eno, Thursday Afternoon (1985)

As the man most responsible for codifying the notion of ambient music, it’d be remiss not to include his work here. And while albums like Discreet Music and Music for Airports are classics of ambient music, we suggest spinning his equally gorgeous mid-’80s effort, Thursday Afternoon. Originally conceived as a soundtrack to a “video painting” of Christine Alicino (which was presented in a vertical format, meaning you had to lie down to view it properly), this hour-long piece sounds simple enough. An acoustic piano (which bears the slightest resemblance to the resonant piano from “1/1” of Airports) slowly moves through a progression as halos of synth glow behind it. It’s soft enough that oft times the piece hovers at the edge of perception. But everything is phased in such a way that the relationships between notes and washes slowly shift. Focus on any one element and the whole grows fuzzy, to where your perception of the piece appears to alter the whole. A fine piece to observe, as Jamaican guru Mooji puts it, “you are the knower of knowledge; you perceive perceiving.”

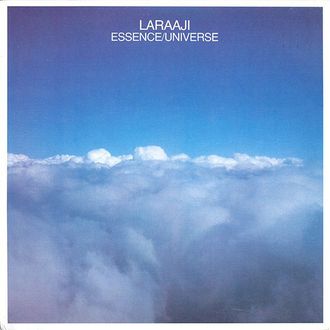

Laraaji, Essence/ Universe (1987)

In a now infamous story, in the late 1970s comedian-musician Larry Gordon was busking in Washington Square Park on his autoharp, eyes closed as he went deep into his performance. Upon opening his eyes, he found a note from Brian Eno, saying he would like to talk about recording. Soon after, Gordon went into Eno’s studio, had his strings run through a light patina of electronic effects and came out with the epochal Ambient 3: Day of Radiance album; a new name, Laraaji (his first name and last name initial combined); and a new career as a conduit of transportive New Age music. He has released numerous cassettes over the years, but few reach the sumptuous highs as this 1987 album. Much like the cover photo suggests (which Laraaji took while on a flight), the album takes you above the clouds. Featuring two extended improvisations on zither, each treated and shaped by producer Richard Ashman, each piece takes you to vistas of gorgeous sound. If there’s the sound of the heavens exhaling to attune your own breathing to, this is it.

Henry Wolff and Nancy Hennings, Tibetan Bells III (1988)

In the midst of classic rock’s golden days in the early ’70s, Henry Wolff and Nancy Hennings decided to hole up in the Island Records studio and make a record with just Tibetan bells and singing bowls. Using little more than struck metal from the Far East and capturing those subtle vibrations on tape, the duo found themselves at the fore of New Age music. They’ve now presented more than a few sequels to their original, and while almost any is a fine entry point into their immersive catalog, Tibetan Bells III features long excursions like “Crossing the Line” and “The Empty Mirror.” Rather than sound your own singing bowl as you sit, allow these two to sound the centering tones of these bells and take you on an inward journey.

Pauline Oliveros/ Stuart Dempster/ Panaiotis, Deep Listening (1989)

In 1971, Pauline Oliveros published a selection of text-based scores called “Sonic Meditations.” Part Fluxus, part listening exercise, part body awareness, part spiritual koan, these pieces might read like “Meditation” No. 5: “Take a walk at night. Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears.” Whether you allow your feet to become ears or not, awareness of the space surrounding you is crucial in meditation. And it’s a concept that became paramount on Oliveros’s 1989 album Deep Listening. Recorded inside of the 2 million-gallon Fort Worden Cistern in Port Townsend, Washington — which has a 45-second reverberation time that suggests the infinite in every utterance — this album explores the sound of the void. That length of reverb demands patience from its players, and so Oliveros’s deep-breathing accordion joins Stuart Dempster’s trombone and didgeridoo, as well as Panaiotis’s low murmurs, the trio converging and filling the very air around them with something approaching sublimity.

Eliane Radigue, Trilogie de la Mort (1998)

A momentous three-hour work that this underappreciated French electronic composer (and devoted Buddhist) made between 1985–93. Carefully filtering the frequencies of her mainstay instrument, the ARP 2500 modular synthesizer, Radigue transforms such circuitry until it’s a celestial hum. A series of early works from that decade were dedicated to the Tibetan yogi Milarepa, while Trilogie tackles a more formidable source, Bardo Thödol, or The Tibetan Book of the Dead. As a slowly undulating drone centers and transports, the work doesn’t feel like an experiment in electronics so much as a pilgrimage towards the divine.

Gas, Pop (2000)

In the past few years, the Japanese notion of “Shinrin-yoku” (or forest bathing) has begun to catch on the West. It was originally coined by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in the 1980s, perhaps as a way to bring more people to their trails, but many today perceive it as a way to be at one with nature. That trend might not have reached electronic music producer Wolfgang Voigt when he was a young boy in Germany, but he wandered through the Königsforst for its meditative properties from an early age. With his Gas project, Voigt pays tribute to the sounds of the forest, a brilliant run of ambient techno that peaks with 2000’s Pop. It opens with gurgling rivers, bird trills, and synths like sunshine twinkling through the branches, before moving deeper and darker. Voigt’s beats turn subliminal as if pounding through the tree trunks. For those looking to visualize a nature walk as they sit in meditation, 2000’s Pop can set you among the pine needles.