This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

What makes a great New York City movie? Not just a movie set in New York — there are plenty of those. We’re talking about a great New York City movie that transcends establishing shots and dodgy accents to immortalize something distinct about this place. The anxious pace of a weekday commute, the philharmonic overlapping of sidewalk talk, the sweaty jockeying for position on any square foot. Great New York City movies find beauty in the rot of Times Square and ugliness in the penthouses of Central Park West. Many reflect the perilous reality of living in Brooklyn today and the Bronx yesterday; others, the urbane fantasy. The best do both. In assembling this list of the greatest New York movies, we laid down a few ground rules: in the interest of fairness, a director could only be represented twice on the list; any selection had to take place mostly in New York City (even if it wasn’t shot in New York City); and, most important, it had to feel deliberately set in one of the five boroughs. Not just in any big city, but here.

101.

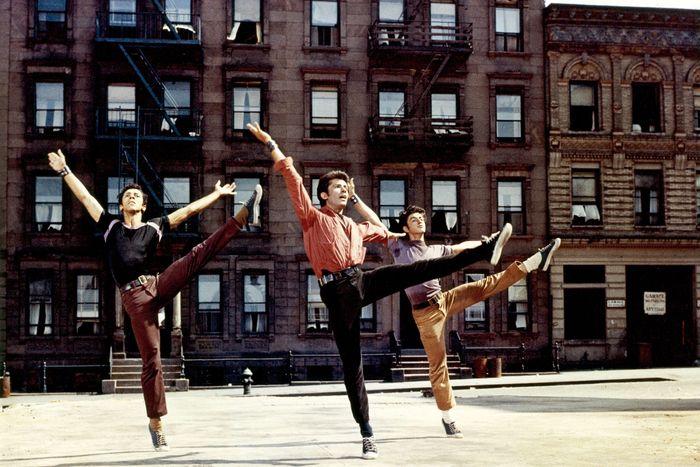

West Side Story (Jerome Robbins, Robert Wise; 1961)

A commercial smash that swept that year’s Oscars, Robert Wise’s film adaptation of the racial-tolerance fable West Side Story feels dated in some ways (the earnest yet stereotypical portrayal of Puerto Rican characters with brownface) and bracingly modern in others, poised between Hollywood backlot fantasy and shot-on-location immediacy. The opening aerial views of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, for example, memorialize the time before a large part of the area, then known as San Juan Hill, was bulldozed in the name of urban renewal. But Wise goes for Technicolor expressionism and deliberately theatrical sets whenever he’s focusing on the Romeo and Juliet–style love story between Polish American ex–gang member Tony (Richard Beymer) and his Puerto Rico–born true love, Maria (Natalie Wood). Leonard Bernstein’s music and Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics are the air that the story breathes and that the dancers walk on. This film is a dream of New York, so beautiful that even tragedy can’t break the spell. —Matt Zoller Seitz

100.

Ghostbusters II (Ivan Reitman, 1989)

No, no, you read that right. The mostly forgotten, supposedly lesser Ghostbusters sequel just happens to be a great New York movie. It may not be as zippy or as inventive as the original, but Ivan Reitman’s 1989 follow-up has one of the most perfect and versatile cinematic fantasy conceits of all time: All the negative energy of New York City is seeping into the sewers and creating a river of paranormal ooze that now threatens to consume the inhabitants. Park benches are coming to life. Fur coats are attacking their owners. The ghost of Fiorello La Guardia is haunting the current mayor. And in order to generate enough good will to defeat the ooze, the Ghostbusters have to bring the Statue of Liberty to life on New Year’s Eve and march it into battle while playing “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher.” It’s all so conceptually deranged that Ghostbusters II might as well be an underground movie. (Honestly, all the terrible special effects probably just add to that effect.) —Bilge Ebiri

99.

Dick Johnson Is Dead (Kirsten Johnson, 2020)

Kirsten Johnson’s remarkable picture is one of the most unlikely works about grief you’ll ever see. Concerned about her elderly father’s growing dementia, the director creates a variety of fictional “deaths” for him, staging them with him as the star. The film is hilarious in its particulars but devastating in its overall impact. It’s also a powerful portrait of a 21st-century New York family: Johnson brings her father from his West Coast home to move into a small apartment with her and her two children (whom she co-parents with their two gay fathers, who live next door). Unlike so many New York films, which are ultimately fantasies about life in the city, this is one of the most electrifyingly honest about how people actually live today — while also being a fantasy (indeed, many fantasies) about dying in the city. —BE

98.

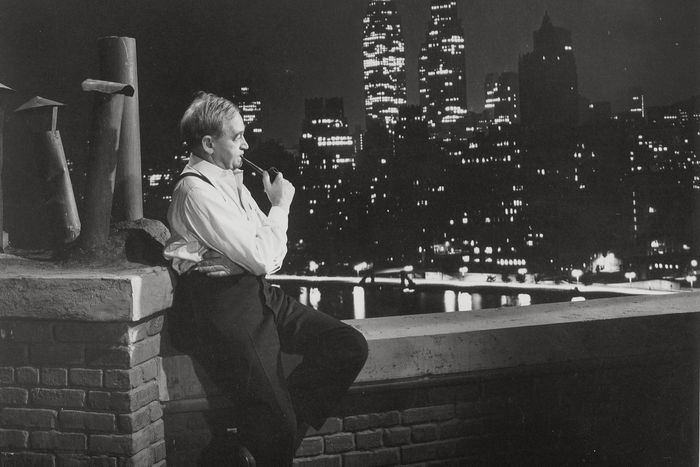

The Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948)

With the coming of talkies in the late 1920s, the well-established business of filming on New York City streets — see Speedy, at No. 72 on this list — nearly vanished. The microphones were too awkward and the ambient noise too great. In 1947, however, the producer Mark Hellinger and director Jules Dassin demanded that their highly explanatory police procedural, at first intended to be titled Homicide, be shot on location. The Naked City is profoundly realist in both conception and execution: Hellinger had been a well-loved New York newspaper columnist and man-about-town before going to Hollywood, and the film’s title and look are drawn from the news photographs of Arthur Fellig, a.k.a. Weegee. The immigrant accents are all ours, too, from the transplanted brogue of the wry police detective (Barry Fitzgerald) to the Yiddish syntax of the soda-fountain proprietor (Molly Picon). One little subplot — young cop gently arguing with his wife about whether spanking their kid is barbaric — feels unexpectedly modern. It all climaxes in an elaborate chase sequence on foot, atop the roadway and into the towers of the Williamsburg Bridge. Poignantly, it was the last thing Hellinger did in his short career: He died at 44, of heart disease, a few days after he saw the final cut. The closing words of his narration linger in pop culture: “There are 8 million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them.” —Christopher Bonanos

97.

Jacob’s Ladder (Adrian Lyne, 1990)

Many films have presented New York City as pure nightmare fuel, but few have done it with as much gusto as Jacob’s Ladder, a period piece about a Vietnam veteran (Tim Robbins) who starts having visions of demons and wonders if he’s the victim of an Agent Orange–like chemical, if he’s suffering from garden-variety mental illness, or if the gates of Hell have actually opened up. Written by Bruce Joel Rubin, who did sort of a “light magic” take on this material in the 1990 smash Ghost, the movie keeps audiences constantly guessing as to what, exactly, is actually happening, while serving up one disturbing supernaturally tinged hallucination/vision after another, including a demon tail emerging from a dancer’s body at a party and smeary Francis Bacon–esque beast faces yowling at Robbins’s character from a passing subway car. The emphasis on mostly squat and nondescript borough architecture keeps the story close to the ground, where it can have easier access to Hell. New York becomes the labyrinth of the hero’s tortured psyche. —MZS

Read about how Adrian Lyne perfected the life-affirming affair film trope ➼

96.

The Odd Couple (Gene Saks, 1968)

Neil Simon — probably the most commercially successful playwright ever to walk the Earth — has fallen way out of style, written off as the quintessential mid-century middlebrow. But his better comedies from the ’60s and ’70s, written for the stage and then adapted for the screen — Barefoot in the Park, Prisoner of Second Avenue, Plaza Suite, and especially The Sunshine Boys — are much more craftsmanlike than you may remember, setups that swing with the precision of a Benrus balance wheel and play with language in lively ways. King among them remains The Odd Couple. Is it the most bulletproof premise ever? Neat neurotic, newly separated, moves in with slobby sports-writer friend, also divorced; hilarity and thrown plates result. The jokes (“I can’t stand little notes on my pillow. ‘We’re all out of cornflakes. F.U.’ Took me three hours to figure out F.U. was Felix Ungar”) always, always land. And when it was put onscreen in 1965, starring Jack Lemmon as Felix and Walter Matthau (at his exasperated best) as Oscar, it teed up the sitcom by which it’s best remembered. It is, when you get down to it, a movie about the inability to find a decent apartment in a hurry — which, right there, cements its spot on any list of New York movies. —CB

95.

Wall Street (Oliver Stone, 1987)

The most important thing that Oliver Stone’s Wall Street did was give birth to Gordon Gekko, the Michael Douglas money manipulator who swore, during a speech, that “greed is good.” In a decade of excess, Wall Street should have served as a cautionary tale, and that Gekko monologue should have been an ironic example of how not to view capitalism. Instead, this portrait of a stockbroker (Charlie Sheen) who delves into insider trading, making himself and Gekko rich, created an image of working in the Financial District that became something to aspire to instead of avoid. Greed is good, and it apparently does not understand irony. As a result, this film has, for many, defined what it looks like to toil among the besuited in lower Manhattan ever since its late-’80s release. —Jen Chaney

94.

Hester Street (Joan Micklin Silver, 1975)

Joan Micklin Silver’s first feature is an epic shot on a shoestring – an ultralow-budget, black-and-white period piece about turn-of-the-century Jewish immigrants to New York – and at times it’s as expansive and powerful as The Godfather Part II. Carol Kane (a surprise Oscar nominee that year) is a revelation as the very traditional wife who moves from the old country with her child to be with her husband. But he has come to America ahead of them and already taken on a mistress. The film nails both his eagerness to assimilate — his fascination with the newness and bracing independence of life in America — and her sadness, confusion, and terror at finding herself seemingly alone in this strange new world. Silver’s direction combines a melodramatic, silent-movie sensibility with an indie-film austerity that makes it hard to pinpoint the period to which the picture belongs. As a result, it’s almost literally timeless. —BE

93.

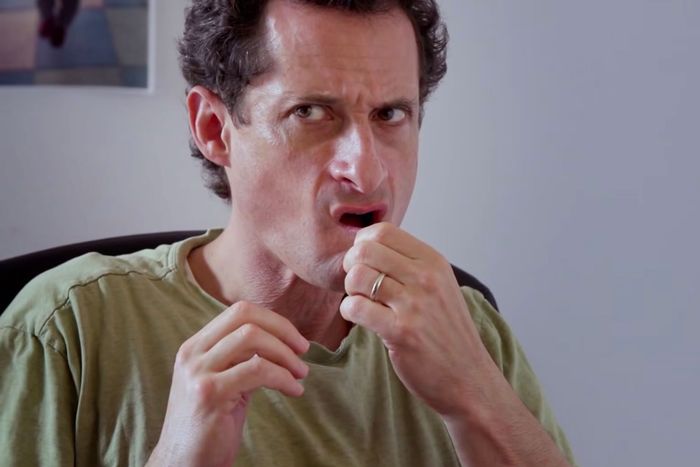

Weiner (Josh Kriegman, Elyse Steinberg; 2016)

Elyse Steinberg and Josh Kriegman’s embedded doc of laughingstock politician Anthony Weiner is like a snort of fine grade New York Post headlines straight to the amygdala. Few movies, narrative or otherwise, have captured the frenzied absurdity of Big Apple politics quite like this. At the start of his career, Weiner used righteous anger like Rembrandt used oils, turning his accusatory howls in the well of the House of Representatives into art. The momentum of the Democratic Party was with him, as was the will of the city. And then came the tweet. After an apology and initial retreat, Weiner, with wife Huma Abedin advising him, decided to run for mayor. That’s where this film picks up (and the story gets juicier). What’s most compelling is how close to great Weiner is. He was born to campaign. You’ll never see a wider smile than Weiner’s as he grabs a Pride flag and parades down Christopher Street. Watching the Brooklyn-born putz piss it all away with more clumsy sexts eventually moves from farce into a kind of cosmic tragedy. Carlos Danger, New York will never forget you. —Jordan Hoffman

92.

Cloverfield (Matt Reeves, 2008)

This found-footage horror film directed by Matt Reeves, written by Lost alum Drew Goddard and produced by Lost co-creator and longtime friend of Reeves, J.J. Abrams, is both old-fashioned, of its moment, and forward thinking. Arriving in theaters a little more than six years after 9/11, its depictions of sudden chaos on this island — people running in the streets, bystanders covered in ash, blackouts and nonstop news coverage — evoke a kind of trauma many were still processing. Then you look at Cloverfield now and it’s remarkable how much it resembles clips on YouTube, Twitter, or TikTok that often surface in national news coverage when a disaster or protest is being covered. What critics found dizzying, disorienting, and perhaps even distasteful more than a decade ago, before the iPhone had video capabilities and social media occupied the cultural space it now owns, looks like something we see all the time. Cloverfield was a throwback and a warning and a portrait of Manhattan panic that, unfortunately, is all too easy to imagine breaking out at any moment. —JC

91.

Uncut Gems (Benny Safdie, Josh Safdie; 2019)

New York is made up of a million miniature universes with their own regulars, rules, and rhythms, and no movie makes that as clear as the Safdie brothers’ hopped-up thriller hinging on a black opal and a six-way parlay. Gemstone dealer Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler) isn’t just a gambling-addicted avatar of chaos careering toward wealth or disaster — he serves as a guide through the warrens of the Diamond District in all its self-contained, single-block glory, a means of understanding its daily thrum. Howard, with his multiple schemes always threatening to collapse on themselves at any one time, is a quintessential hustler, but he’s also a means of understanding an underappreciated truth of the city, which is that the luxurious and the seedy don’t just coexist but more often than not overlap, neither negating the other. —AW

90.

The Blank Generation (Ivan Král, Amos Poe; 1976)

Miracle of miracles: a movie about punk that itself lives up to the punk aesthetic! Amos Poe and Ivan Kral’s 1976 portrait of the downtown music scene — shot at places like CBGB, the Bottom Line, and Max’s Kansas City — presents some of the signature acts of the era, like the Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, and Television, in raw, freewheeling black-and-white 16-mm. footage, accompanied by scratchy recordings that in no way match what’s being sung. The result is a concert documentary like no other — disorienting yet electrifying— and a film that embodies the aching, agitated grandeur of both the chaotic metropolis from which it emerged and the Richard Hell song after which it’s named. —BE

89.

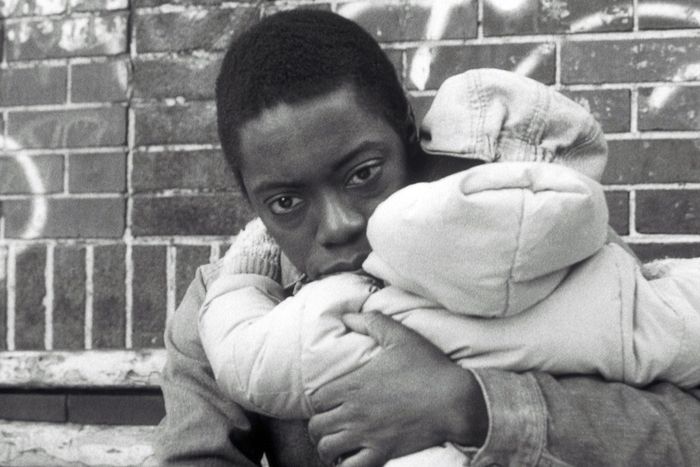

Sidewalk Stories (Charles Lane, 1989)

Charles Lane’s 1989 movie isn’t set in the past, but it’s styled to evoke it, taking the format of a 1920s silent with no diegetic sound at all until the very end. More specifically, it follows the format of Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid, with which it’s in constant conversation. Like the Tramp in that 1921 film, Lane, the star and writer and director, plays a character who doesn’t have a name so much as he has a designation: the Artist. And like the Tramp, the Artist finds himself caring for an abandoned child (played by Lane’s own daughter, Nicole Alysia), though in his case, he becomes a surrogate father only after the toddler’s biological one gets shot in a downtown alley. That’s the daring charm of Lane’s film — it uses its nostalgic mode to give a fablesque charm to a story about the poverty and violence the city was grappling with at the time. It also places its Black hero in a film tradition that included almost no Black faces, then demands the audience consider that, in a real-world context, he’s one of many street artists and buskers who’d be passed by unseen. —AW

88.

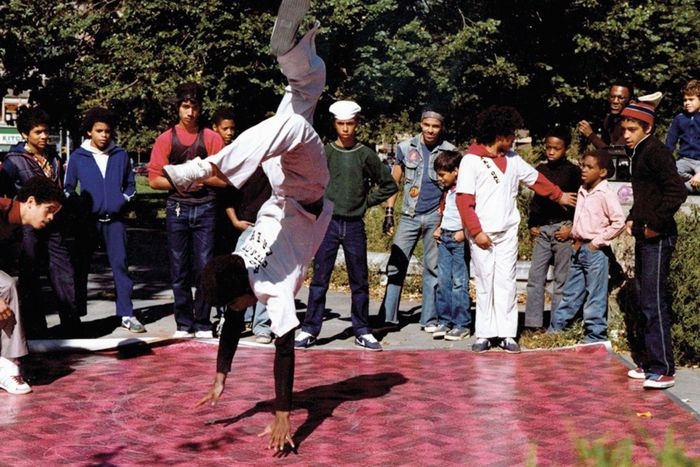

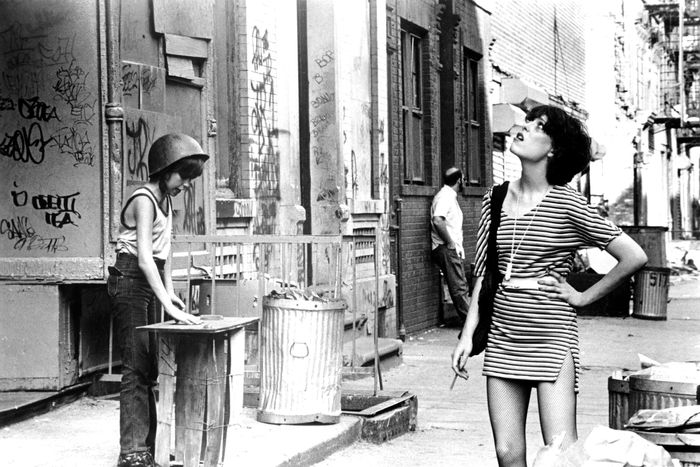

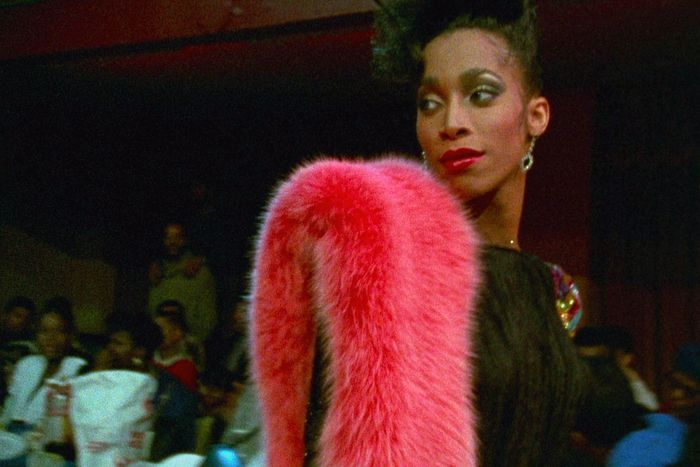

Wild Style (Charlie Ahearn, 1983)

Charlie Ahearn’s Wild Style was the first hip-hop movie, but just barely — bigger productions like Breakin’ and Beat Street were already under way when this no-budget indie effort came out in 1983, released and marketed via grass-roots methods. But its authenticity and warmth have allowed Wild Style to endure. It’s the story of a supremely talented graffiti artist, Ray (played by real-life graffiti legend Lee Quinones), who is hired to do a huge mural for a big upcoming rap show by a local underground hotshot (played by Fab 5 Freddie, who co-produced and co-wrote the film) while also pining for his ex-girlfriend and contemplating a move into “respectable” painting. The movie is filled with scenes involving real-life rappers, artists, and breakdancing crews. It is, in effect, a musical, but it wouldn’t take much editing to turn it into a documentary. And it’s a movie about the art world, but not that art world: Our heroes write on the subway trains in the yards by night; in the morning, they watch those trains roll out into the city, roving canvases of their work going out to every corner of New York. But what distinguishes Wild Style is that even though it depicts the rough, working-class world of the Bronx with honesty, it doesn’t try to sell us a narrative of transcendence, nor does it try to fetishize violence or poverty or spiritual despair. Its characters want to make their neglected neighborhoods beautiful by filling them with color and music and movement, but they don’t want to escape this place. It’s home. —BE

87.

The Women (George Cukor, 1939)

Famously, no men appear onscreen in George Cukor’s biting comedy, though they are constantly talked about and fretted over and competed for by the characters we do see, less for their qualities as husbands than as sources of income, stability, and class elevation. As a portrait of wealthy Manhattan society spouses (and a few upstart contenders to their thrones) duking it out in ladies’ lounges, salons, and couturiers’ fitting rooms, The Women could be regarded as a classy, deliciously done predecessor of the Real Housewives of New York. But it’s also an endlessly compelling look at the echelons of the Upper East Side as a kind of plush prison yard from which the characters can’t seem to escape. This homosocial daytime society they move through feels so terribly claustrophobic that when the brokenhearted Mary Haines, played by Norma Shearer, heads off to Reno to get a speedy divorce, she runs into multiple women she knows. —AW

86.

On the Bowery (Lionel Rogosin, 1956)

Many New Yorkers pine for the adventure of the “old” Times Square but few share that sentiment about the Bowery. The downtown avenue, a Lenape footpath prior to European settlement, later connected various farmlands and got its name from an old Dutch word for farm. Its notoriety for drunkards and flophouses began during the Civil War, then the erection of the Third Avenue elevated train made it literally shadier. Lionel Rogosin’s mid-’50s docufiction works in the spirit of Robert Flaherty, shooting real subjects in real scenarios, though not quite what we’d call documentary today. Ray is a Southerner in his mid-30s looking for work and trying to stay away from the bottle, and Gorman is the old souse who feels guilty for taking advantage of him when he’s too blitzed to notice. The days are long and the nights are longer as these desperate men drink muscatel and Rhinegold at 15 cents a glass. The plot, such as it is, hardly exists, as with any barroom drunk’s rambling story. It’s a mesmerizing document and fascinating window into another gentrified neighborhood’s past. —JH

85.

The Warriors (Walter Hill, 1979)

Controversial both for the stylized warfare it depicted onscreen and the clashes that broke out between hyped-up young moviegoers in the audience, The Warriors finds ace action director Walter Hill (48 Hrs.) envisioning a gang’s nighttime journey home to Coney Island as a Homeric journey interspersed with outbursts of balletic violence. The story begins with a summit in Van Cortlandt Park during which a truce is explored, with the aim of allowing the gangs, who outnumber cops three-to-one, to rule the city (a perfect reflection of ’70s paranoia about street gangs and the breakdown of law and order in big cities). But the leader who proposes the power-sharing arrangement is promptly assassinated and his death blamed on the Warriors, who spend the rest of the night trying to make it home in one piece. A relic from a time when the city wasn’t covered wall-to-wall by video surveillance, Hill’s movie transforms New York’s concrete canyons into the urban equivalent of a haunted forest in a fairy tale: a place where Jungian manifestations of the characters’ anxieties lunge from the darkness, fangs bared. —MZS

84.

The Hottest August (Brett Story, 2019)

Brett Story’s haunting documentary snapshot of the city during the month of August 2017 could very well turn out to be a time capsule of a tipping point, a moment of leveling off right before things start to seriously go downhill. It’s not just a film about climate change, though climate change casts a shadow over many of the expectation-defying interviews Story does with New Yorkers across all boroughs, lounging on beaches and working in call centers and going about their lives of work and leisure. No, what The Hottest August so deftly manages to evoke is that grander, vaguer sense of impending doom that can feel like it’s pressing down on all of our lives these days, a karmic feeling of bills coming due that has always been part of life in the city — while also noting that not everyone has the luxury or the mental space to constantly contemplate imminent dystopia. —AW

83.

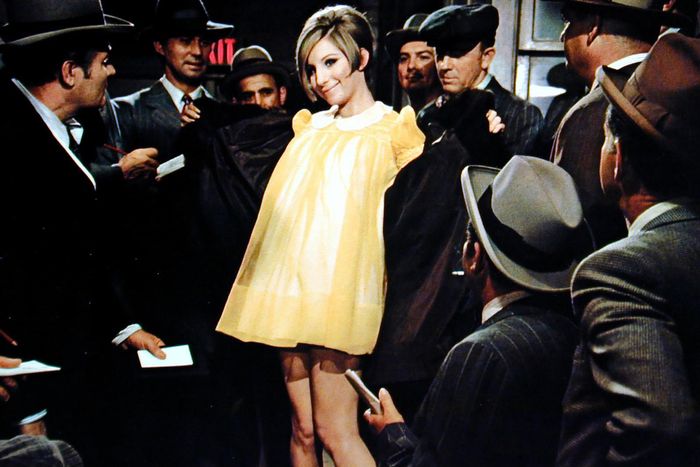

Funny Girl (William Wyler, 1968)

“She has the best timing since Mae West, and is more fun to watch than anybody since the young Katharine Hepburn.” That’s what film critic Roger Ebert wrote about Barbra Streisand in 1968, when she made her film debut in Funny Girl (which she’d starred in on Broadway) as the young Fanny Brice following years of success as a stage performer and recording artist. Directed by Hollywood veteran William Wyler in one of his final assignments, and unfortunately indicative of a period when musicals were becoming bloated, visually dull, and glacially paced, the movie is most notable as a record of the moment when Streisand became an international superstar, beloved and acclaimed enough to tie the great Hepburn herself (then starring in The Lion in Winter) for Best Actress at the Oscars. (“Hello, gorgeous,” she said, beaming at the statuette.) Streisand is herself a New York legend, and her three films as a director (Yentl, The Prince of Tides, The Mirror Has Two Faces) are all rooted in the physical, cultural, and emotional experience of New York City that she channeled as an actress and singer. As Brice, her mix of brittleness, vulnerability, pluck, and intense feeling turn her into something akin to the spirit of the city itself: a Jewish, Lower East Side, working-class force of nature, negating previous standards for beauty and glamour and replacing them with her own innate fabulousness. —MZS

82.

Saturday Night Fever (John Badham, 1977)

Is Saturday Night Fever, based on the New York Magazine story “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night,” important because of the contents of the actual movie, or because of what the movie came to represent? As with Wall Street, it’s hard to disentangle the two. The story of Tony Manero (John Travolta in the performance that made him a movie star), a Brooklyn guy who works at a hardware store during the day and hits the discos at night, establishes the fantasy that hitting the light-up dance floors in Manhattan is the ultimate nightlife experience. This film shoved the disco movement fully into the mainstream, yielded a soundtrack that practically became the national soundtrack during the end of the 1970s, and made pounding the pavement in Brooklyn, as Travolta does in the movie’s famous opening sequence, into an iconic sexy strut. Tony, like many in the outer-boroughs, may have been barely surviving, but Saturday Night Fever made it look enticing to be staying alive. —JC

81.

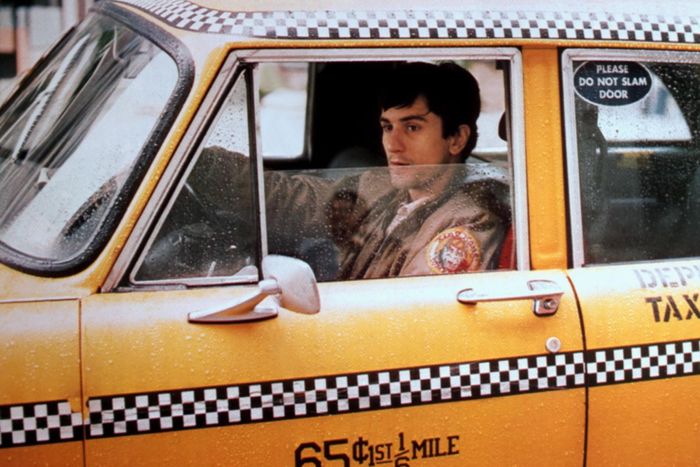

Midnight Cowboy (John Schlesinger, 1969)

Forever notable as the first and only X-rated feature to win an Oscar as Best Picture, this adaptation of James Leo Herlihy’s novel earns its reputation as a classic not through its sexual encounters, which are tame and arty even by 1960s porno standards, but its depiction of the friendship between Joe Buck (Jon Voight), a wannabe gigolo from Texas, and Ratso Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), a grubby street hustler in frail health. Shot on location in New York City, often without permits and with regular citizens unknowingly serving as extras (the “I’m walking here!” moment where Ratso and Buck nearly get run over by a cab was an improv), director John Schlesinger embraces New Hollywood’s then-recent obsession with documentary immediacy and cranks it up. The end product is a rare portrait of what it feels like to survive in New York when you’re freezing your ass off and don’t have two nickels to rub together. One of the most powerful scenes is a throwaway moment: Joe, momentarily estranged from Ratso, spots him through the glass at a coffee shop, and they’re both so lonely and brutalized by the city that they smile at each other in relief, forgetting what they were mad about for all of two seconds. —MZS

Read Brenda Vaccaro on Schlesinger’s documentary-style filmmaking ➼

80.

If Beale Street Could Talk (Barry Jenkins, 2018)

If Beale Street Could Talk proves the pleasures of turning our gaze toward the interior lives of Black folks in 1970s Harlem are endless. Jenkins and his collaborators (composer Nicholas Britell, cinematographer James Laxton, the bruising actor Stephan James and a powerful Regina King) casts the grit, beauty, and textures of James Baldwin’s novel in an amber glow, tipping into a melancholy romanticism that reflects the pull of the city itself. —Angelica Jade Bastien

79.

The Clock (Vincente Minnelli, 1945)

Before Before Sunrise chimed The Clock. Robert Walker stars as a yokel soldier with 48 hours to kill in NYC before shipping off to the European theater. (The movie was released two weeks after V-E Day, but who can predict these things?) Flummoxed by the city’s skyscrapers, he cowers in Penn Station, meeting cute with Judy Garland after he inadvertently trips her. A mad dash to fix her heel before a cobbler leaves work sets the recurrent theme: The clock is always ticking. The pair schmooze on a Fifth Avenue double-decker bus, in Central Park, and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (All of this re-created, at great expense, by Vincente Minnelli on the MGM lot.) A date to meet “under the clock” of the Astor Hotel — where today one finds a ’70s-style slab-of-concrete home to the Minskoff Theatre and MTV’s window-facing studios where Total Request Live snarled traffic for a decade — leads to an all-night romp with a loquacious milkman and Keenan Wynn. If this doesn’t inspire a last-minute race for a marriage certificate, what will? Also: If you’d like to see a similar movie, but with three servicemen and even more Leonard Bernstein songs, keep reading. —JH

78.

Park Row (Samuel Fuller, 1952)

Former newsman and pioneering indie director Samuel Fuller put his heart and soul into this fevered period noir — named after the downtown street where New York’s journalism business used to be based — about an irascible reporter who starts an alternate, muckraking paper after getting fired from the city’s big daily. Among the many campaigns the new paper devotes itself to: raising money for a pedestal for the brand-new Statue of Liberty! Filled with nods to icons of journalism history, including Benjamin Franklin, John Philip Zenger, and Horace Greeley, the film is a love letter to newspapers (it opens with a roll call of the nation’s papers) as well as a terrifically heated drama about morality, ambition, and collective action. The conflicts in the film between access and integrity, between provocation and honesty, are ones we’re still dealing with to this day. —BE

77.

New Jack City (Mario Van Peebles, 1991)

The most mainstream of 1991’s first wave of so-called hood films, Mario Van Peebles’s New Jack City’s influence on pop culture can’t be understated. It didn’t just give us the Wesley Snipes crying meme; it gave us Ice-T as the cop-who-cares and popularized the Kangol hat with the wider culture. Set at the dawn of the ’80s crack era, Snipes and his Cash Money Brothers create a drug-dealing fortress in Harlem’s Graham Court (past residents have included Zora Neale Hurston and Hugh Masekela; current average rental price is $3,094). Ice-T, Van Peebles, and Judd Nelson join forces to take down the community-killing kingpin. They enlist Chris Rock as a struggling ex-abuser in a clinch role that proved the nascent SNL star had tremendous range. The soundtrack was a sensation, with “New Jack Hustler” from Ice-T, plus the “For the Love of Money/Living for the City” medley from Queen Latifah, Troop, and LeVert as highlights. A major shootout at Grant’s Tomb (following a Keith Sweat performance) is one of many terrific uptown-location moments, and the opening scene ranks with Manhattan and Spider-Man for best appearance by the Queensboro Bridge. —JH

76.

The Heiress (William Wyler, 1949)

What lands Wyler’s perceptive drama, starring Olivia de Havilland and Montgomery Clift in some of the most memorable turns of their dynamic careers, on this list is its emotionally fraught portrait of the wealthy, exploring how ideas of power, gender, and personal need run (and ruin) the upper echelons of New York City in the 1850s (and today, for that matter). The Heiress’s best scene is undoubtedly its triumphant ending, but every preceding moment the kindly spinsterish figure Catherine Sloper (de Havilland) has to spend contending with her rich father (Ralph Richardson) who denigrates her and a potential lover who has sights on her money (Clift) is tantalizing. Crafting your own destiny, even with money in a city concentrated with it, is damn near impossible until you wrest control from the patriarchal maw. —AJB

75.

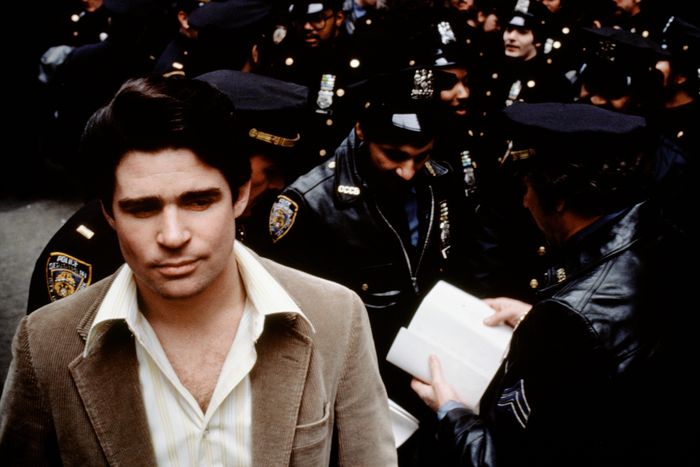

Prince of the City (Sidney Lumet, 1981)

With the cap at two-movies-per-director, we know which Sidney Lumet title ranks higher on the list, but that leaves many different choices for No. 2. Prince of the City may not be as famous as Serpico, The Pawnbroker, The Wiz, or Network, but it’s a movie that deserves a second look. (It is to Serpico as Casino is to GoodFellas.) Treat Williams stars as a DEA agent on a crooked squad, roiled by guilt. He agrees to an internal-affairs investigation, but on one condition: He will not rat out his partners. The bulk of this 167-minute picture is the slow-motion realization that he’s going to have to do just that. The film is based on former NYPD deputy commissioner Robert Daley’s nonfiction best seller, and hardcore time-capsule images of economically busted New York are bursting from every frame. The courtrooms are brown, the streets are blue, and everyone looks miserable. Pre–Law & Order Jerry Orbach as Detective Gus Levy ought to be enough of a draw, but elsewhere in the cast you’ll find Bob Balaban, James Tolkan, and Cynthia Nixon. —JH

74.

The Fisher King (Terry Gilliam, 1991)

Terry Gilliam’s delirious rom-com-fantasy-adventure-satire-drama (yes, it is all of those things, and more) starts off at the top of New York City — in the hermetically sealed world of rich jerk shock-jock Jeff Bridges — makes its way down, then goes even lower: He falls from grace, becomes an alcoholic video-store manager, and then, in a moment of suicidal weakness at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, is saved by homeless, loopy knight-gallant Robin Williams, who introduces him to the city’s truly downtrodden. Besides being an emotionally ruinous look at the city’s brutal, downright feudal class system, and the invisible social barriers between the powerful and the dispossessed, it’s got several of the greatest New York movie set pieces ever, including the spectacle of Grand Central suddenly transforming into a ballroom — a brief, fleeting (and, of course, imaginary) moment when a station full of hurried strangers somehow manages to stop and connect. —BE

73.

Marty (Delbert Mann, 1955)

An influence on subsequent East Coast prole dramas ranging from Joe and All in the Family through The Sopranos, Marty is the first of many film adaptations of 1950s live TV dramas that went on to become more acclaimed and iconic than its source. Both versions were written by Paddy Chayefsky (Network) and directed by Delbert Mann (Lover Come Back, That Touch of Mink); it tells of a shy Bronx butcher named Marty (Ernest Borgnine, replacing Rod Steiger, star of the TV version) who lives a modest and repetitious existence with his mother, then finds meaning and purpose through his love for a high-school science teacher named Clara (Betsy Blair, replacing Nancy Marchand, who originated the role; this was Blair’s industry comeback after having been blacklisted). Exteriors were shot on location in the Bronx and showcase mid-century elevated-train lines. This was also a major success for its production company, Hecht-Hil-Lancaster, which was co-founded by former East Harlem resident Burt Lancaster; the company would go on to produce many classic shot–in–New York dramas, including The Sweet Smell of Success. —MZS

72.

Speedy (Ted Wilde, 1928)

Until the 1920s, when it gradually slipped away to California, the film business was centered in New York City, and Harold Lloyd — the third of the great troika of silent comedians, along with Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton — made his final silent feature mostly on our streets. His character, Harold “Speedy” Swift, holds several jobs over the course of the film (and some of the humor comes from his attempts to hang onto them), but in the central sequences, he’s first a New York cabbie, then a streetcar driver facing down a nefarious tycoon who wants to seize control of the transit line. This being a slapstick silent comedy, those setups occasion a whole bunch of car chases, and even now it’s still a little thrill to see these rickety early automobiles slinging their way through traffic on, among other places, East 34th Street. (Some scenes look to have been assembled using back-projection techniques, but quite a few were obviously, unnervingly filmed in real time on real streets in real traffic. In one, the streetcar crashes into an el-train pillar, an unscripted collision that was turned into a plot point.) In the most famous of the chases, Speedy picks up none other than Babe Ruth, who was truly the biggest celebrity in America at the time. He drives the Babe to Yankee Stadium at death-defying speed, excitedly chatting up his famous passenger over his shoulder throughout, nearly crashing at every turn. You could perhaps come up with a more New York–y set of circumstances than reckless cabbies, nefarious business practices, and sports megastardom, but I doubt it. —CB

71.

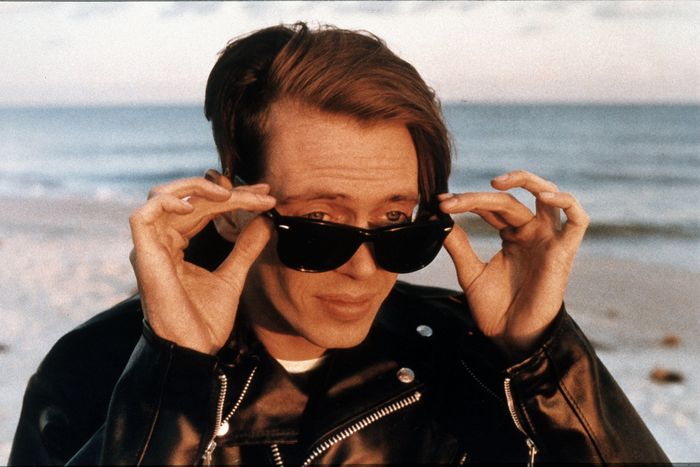

Desperately Seeking Susan (Susan Seidelman, 1985)

Back in 1986, Susan Seidelman’s film was much hyped as the big feature-acting debut of one Madonna, and it makes for both a great star vehicle and a fascinating look at several New York–area subcultures. Rosanna Arquette is the very picture of submerged fabulousness as a bored Jersey housewife who becomes fascinated by a woman named Susan who is a regular in the personals pages of a local paper. Madonna is Susan, a scrappy downtown hustler who has gotten herself embroiled in a vague scandal involving the Atlantic City mob (a subplot treated with such indifference that the film practically becomes a polemic about narrative priorities). One sudden case of amnesia later, Arquette is journeying through a post-punk Lower East Side wonderland and romancing hunky Bleecker Street projectionist Aidan Quinn, while Madonna relaxes in a foofy cocoon of bourgeois suburban splendor. Despite being very much of its time, the film seems to have been made with an eye toward later nostalgia: Watching it, you can lose yourself in its energetic, colorful, unpredictable milieu, even though the world being presented is a highly idealized variation on itself — the way it’d like to be remembered, instead of the way it most likely was. —BE

70.

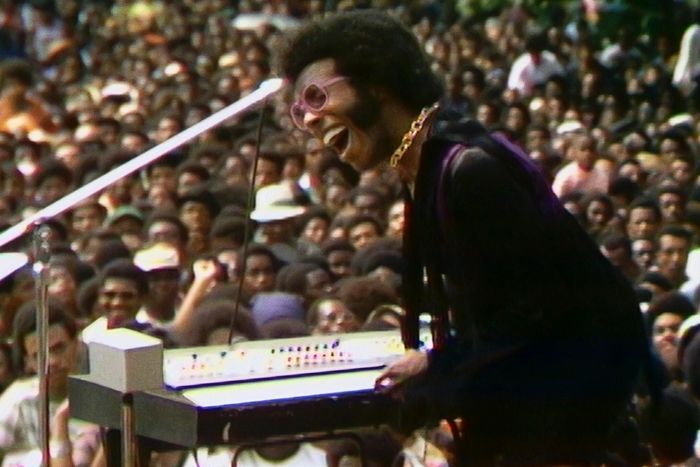

Summer of Soul (Ahmir Khalib Thompson, 2021)

Woodstock has long been considered the musical event of the summer of 1969. But this vibrant documentary argues that maybe history didn’t have all the facts. Using footage from the Harlem Cultural Festival that had been tucked away for decades, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, making his directorial film debut, shows us the many Black artists who brought the Harlem community to what was then called Mt. Morris Park — Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sly and the Family Stone, Mahalia Jackson, and more. If Questlove had decided to piece together highlights from their performances, this still would have been an extraordinary film. But he goes further, not only documenting the moment and what it meant for a marginalized New York neighborhood, but recontextualizing key national events. That includes the moon landing, which is often hailed as a galvanizing, optimistic moment for the whole country. But some folks at the Harlem Cultural Festival saw it differently. “Never mind the moon,” one attendee told a CBS News reporter. “Let’s get some of that cash in Harlem.” It also tempers the singular reverence for Woodstock, the famous hippiefest held 100 miles outside the city that has long been deemed the defining moment of not only the summer of ’69 but a generation. The thing is generations are not monoliths. Around 300,000 people showed up in Harlem to see some of the greats from rock, gospel, R&B, the blues, and Afro-Latino genres do their thing. Summer of Soul makes sure we remember that, and get to hear what they heard on some hot, special days well worth preserving. —JC

69.

God Told Me To (Larry Cohen, 1976)

A repository of 1970s fears of urban decay, random violence, mass murder, UFOs, goverment conspiracies, and cult machinations, this thriller from schlock maestro Larry Cohen (It’s Alive!, Q) starts with a sniper killing 15 random pedestrians with a rifle from his perch in Times Square and gets weirder from there. Tony Lo Bianco stars as Detective Peter Nicholas, who fails to talk the sniper down (“God told me to,” the man says before leaping to his death). He suspects a connection between that tragedy and the random mass murders that follow (including two more mass shootings and a mass stabbing) and eventually uncovers a mystery that feels like an unholy fusion of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Rosemary’s Baby, The Fury, and half the conspiracy thrillers released during the ’70s. New York is presented as a mecca for madness, a nexus of every chaotic and sinister impulse obsessing Americans at that time. —MZS

68.

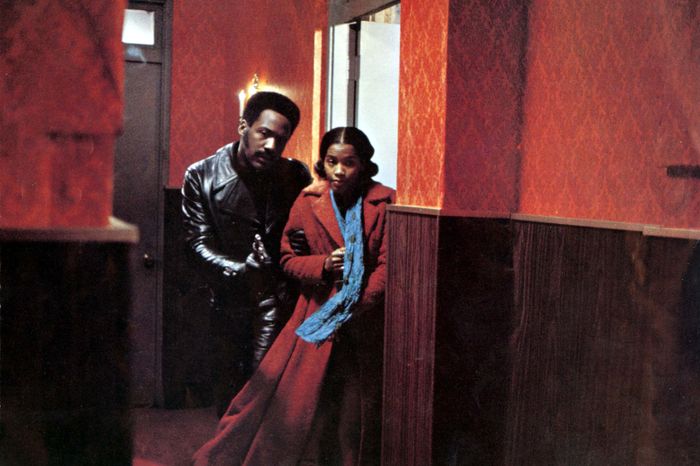

Across 110th Street (Barry Shear, 1972)

It’s mostly remembered for the great Bobby Womack title song. (You can hear his later rerecording of it over the credits of Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown.) But if you want a hard — and I mean hard — look at 1970s New York City, this makes The French Connection look like Bambi. Three men make off with a huge amount of cash from a Harlem bookmaking operation, killing five gangsters (two of whom are Mafiosi) and two cops. The rest of the film is a pair of manhunts: The police are trying to find the thieves before the gangsters exact revenge. The Black gangsters and the Italian ones are in league but also in conflict, and the same goes for the Black and Italian cops at the movie’s center, all of it mirroring a demographic shift that New York as a whole was undergoing. Police captain Mattelli (Anthony Quinn) is a veteran operator, on the take from the local power brokers and out of step with the times, and he’s challenged by the young Black lieutenant (Yaphet Kotto), who is trying to do things right, refusing bribes and yanking Mattelli back when he tries to beat a confession out of a young junkie. The white authority figures, both police and crime bosses, are openly racist. (If you find it hard to handle heavy use of the N-word, this may not be the film for you.) Apart from Kotto’s character, virtually everyone with any power at all is pretty bad news. All of this complex back-and-forth plays out in maybe the grubbiest set of city location shots you will ever see: beat-down and sweaty tenements, garbage-filled vacant lots, a filthy old precinct house, most of it shot dark and close-up. The only thing that occasionally leavens the visual grimness is the exuberant lapels and hats, straight out of the Flagg Bros. catalogue. —CB

67.

Saving Face (Alice Wu, 2004)

The main character of Alice Wu’s undersung Chinese American landmark, a surgeon played by Michelle Krusiec, is closeted when she goes home to Flushing and tentatively, if not comfortably, out in the life she’s made for herself in Brooklyn. Then her mother (Joan Chen) turns up at her doorstep pregnant and disgraced, and that careful compartmentalization starts to collapse as the two women start sharing a small space with all their respective secrets. Wu’s film is a salty-sweet romantic comedy, but it’s also an enduringly sharp exploration of a generational immigrant divide that’s enabled by everything that both sides leave unsaid. Its heroine may still live in the city in which she grew up, but bridging the distance between who she is now and the expectations of the community she came from is a lot more complicated than just taking the 7 train. —AW

66.

The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971)

One of the first cop thrillers to connect with mass audiences by lamenting the minimal civil-rights protections guaranteed by the Supreme Court case Miranda vs. Arizona, this brutal William Friedkin riff on a real case swept the Oscars and became a smash. It also made folk heroes of the real-life inspiration for its buddy-cop heroes, narcotics detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, who led a late-’60s operation that brought down a French heroin ring. Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider star as the detectives’ fictional avatars, volatile bully Popeye Doyle and his comparatively level-headed partner Sonny Grosso. Friedkin shot much of the film (including the high-speed chase scene under Brooklyn’s D elevated-train platform) without permits, with a heedless verve that might’ve gotten people killed had one or two things gone wrong. The plot is so dense that Mad titled their parody What’s the Connection?, but it doesn’t matter: Shaft writer Ernest Tidyman’s script, Friedkin’s direction, and Gene Hackman’s rabid bulldog performance whisk the viewer along like a terrified suspect handcuffed in the back of Popeye’s babyshit-brown Pontiac LeMans. The nihilistic and thoroughly deflating ending is not just characteristic of ’70s thrillers but feels like a premonition of present-day ACAB sloganeering. Nearly every officer in this film is an entitled, macho brute who treats NYC as a playground where adult men go to smash cars and heads. —MZS

65.

Working Girl (Mike Nichols, 1988)

Mike Nichols’s riff on princess fantasies centers on working-class Tess McGill of Staten Island (Melanie Griffith), who gets her bachelor’s degree in business via night classes and is about to quit her existing job over sexism when she gets hired as an assistant to Katherine Parker (Sigourney Weaver), a glass-ceiling-shattering trader who goes on to betray Tess by stealing one of Tess’s best ideas. What follows is a combination revenge/comeuppance comedy and a screwball love story between Tess and investment broker Jack Trainer (Harrison Ford), with Tess relentlessly pursuing the acknowledgment and recompense that she believes she’s earned despite having her class and gender held against her. Catfight melodrama is undercut by a lovely closing scene showing that Tess is going to be a very different girlboss pioneer than Katherine, mentoring the next generation of executive women and treating them as natural allies rather than potential thieves of patriarchal largesse. There’s luscious helicopter photography of 1980s New York (including a hero shot of the Twin Towers); a soaring, anthemic Carly Simon theme song (“Let the River Flow”); and a scene where Harrison Ford changes shirts in a glassed-in office, prompting applause from the secretarial pool. Like Saturday Night Fever, Working Girl presents Manhattan as an Emerald City on the Hudson that outer-borough dreamers think of as a million miles away, even though anyone with a token could get there by subway. —MZS

64.

I Like It Like That (Darnell Martin, 1994)

Darnell Martin’s first feature is an exuberant, colorful explosion of life, love, and New York noise. Lauren Velez and Jon Seda live on the loudest block in the Bronx, where neighbors either cheer as you make love or bang on the ceiling with a broom. Their three kids are tornadoes of chaos, capturing how children can be funny and frustrating at the same time. A dumb decision during a blackout lands Seda’s Chino in jail for a hot minute, so Velez’s Lisette needs quick cash to bail him out. One far-fetched series of events later she ends up as the new assistant (and Latinx interlocutor) for a record exec played by Griffin Dunne. Discovery of past marital infidelity then turns the already antic household further upside-down with Martin’s frames bursting with energy and bright ’90s colors. (The title song is performed by a supergroup featuring Ray Barretto, Sheila E., Tito Nieves, Tito Puente, Dave Valentin, Paquito D’Rivera, and Grover Washington Jr.) Notable is Jesse Borago’s turn as Lisette’s trans sister, Alexis. Though a cisgender man would be inappropriate for the role today, in 1994 the character was treated with depth and care, and Borago’s performance is warm and wise. —JH

63.

The Squid and the Whale (Noah Baumbach, 2005)

The Royal Tenenbaums’ sleazier, sadder real-world cousin, this Wes Anderson–produced, 1980s-set drama by writer-director Noah Baumbach centers a white Park Slope family of creative-academic types, led by married writers whose union is doomed and whose sons 16-year-old Walt (Jesse Eisenberg) and 12-year-old Frank (Owen Kline) are depressed and alienated and have started to act out. The father, Bernard Berkman (Jeff Daniels), is still coasting on the fumes of his early success; his disaffected wife Joan (Laura Linney) is on an upward creative slope and has started sleeping with Walt’s tennis instructor (William Baldwin). Baumbach drew on his own experience as the son of two New York film critics–academics, Jonathan Baumbach and Georgia Brown. His eye for pretension, arrogance, and self-deception is filet-knife sharp and the Reagan-era details are impeccable, from the reuse of a bit of Tangerine Dream’s score from 1983’s Risky Business to the quotation of a 1970s Saturday-morning Schoolhouse Rock! segment (“Number Eight”) that the brothers would’ve watched as kids. —MZS

62.

In The Cut (Jane Campion, 2003)

The East Village is a landscape lush with carnal possibility and lethal danger in this unfairly maligned 2003 movie, which once upon a time had people pearl-clutching because it dared show Meg Ryan having sex — and with an absurdly hot, maybe murderous Mark Ruffalo, even. Casting America’s sweetheart was absolutely by design for Jane Campion, whose sultry, seedy vision of New York gets served up as a direct contrast to fairy-tale notions of romance, the city awash in a sensual awareness that constantly threatens to take a turn toward the dark. It’s a startlingly female-gaze-y take on the idea of the erotic thriller, as well as one of the great tail-end cinematic cases for then-contemporary New York as a menacing place. —AW

61.

Born in Flames (Lizzie Borden, 1983)

The Lower East Side of the early 1980s was such a free-for-all, a combination of urban hellscape and artists’ commune, that it didn’t take much work for an enterprising low-budget filmmaker to reimagine it as science fiction. And that’s exactly what visual artist turned filmmaker Lizzie Borden did when she crafted this dynamite stick of no-budget “No Wave” filmmaking, a documentary-style account of a post-revolutionary future and the women who fight for space in it. The politically minded filmmaker was synthesizing ideas and arguments specific to the picture’s time and place, but what’s most striking today is its timelessness and prescience — its conversations about intersectionality, sex work, social justice, and police brutality have only grown more urgent, and its World Trade Center–set closing images are even more disturbing today. —Jason Bailey

60.

Baby Face (Alfred E. Green, 1933)

“You must use men! Not let them use you,” the cobbler Adolf (Alphonse Ethier) tells Lilly Powers (Barbara Stanwyck, a slinking powerhouse in the role), before instructing her in the work of existentialist Fredrich Nietzsche. The bold statement charges Lilly and the pre-Code-Hollywood-era film around her, leading the character from the small Pennsylvania town she calls home to New York City. And what better place for a woman and her best friend (Theresa Harris) to chase men and power? Lilly’s ascends in the glittering metropolis thanks to her sexual wiles and the men interested in a taste of them. After each of her successful seductions, Green’s camera pans up the exterior of the bank where she works, moving from floor to floor, making obvious her rise and what big city dreaming requires of a person. —AJB

59.

Tootsie (Sydney Pollack, 1982)

New York can make a struggling actor do surprising things. For Michael Dorsey, played by Dustin Hoffman, his surprising thing is pretending to be a woman named Dorothy Michaels so he can get cast on a soap opera. A lot of the gender politics in Tootsie are outdated, and too much of the comedy is mined from the idea that a guy doing feminine things is inherently hilarious. But the movie remains an incredibly entertaining touchstone because of the extent to which Michael, and Hoffman, commit. Quickly, Dorothy ceases to become a masquerade and morphs into her own take-no-b.s. human being, one who will hit a handsy co-worker over the head with a clipboard if she has to. The imagery shaped by director Sydney Pollack is indelibly New York: Dorothy’s red bouffant wig emerging from the crowd on a Manhattan sidewalk; Michael, casually shoving a mime in the middle of Central Park; Michael, as Dorothy, blindsiding his agent George (played by Pollak) at the Russian Tea Room, where he reveals he’s been hired to play a female nurse on Southwest General. But both Michael’s and Dorothy’s attitudes — stubborn, creative, insistent on standing up for themselves — may be what makes Tootsie a true New Yorker’s story. —JC

58.

Dead Presidents (Albert and Allen Hughes, 1995)

Allen and Albert Hughes followed up their explosive 1993 debut feature Menace II Society with this ambitious drama, which arrived with a lot of hype but was met with both mixed reviews and tepid box office. Since then, it’s rightly been reclaimed as a masterpiece. It’s the story of a young Bronx man (Larenz Tate) who goes off to fight in Vietnam (alongside his best friend played by a young Chris Tucker in a rare dramatic role), experiences untold horrors, then comes back to a world that is almost as broken and traumatized as he is. The film goes from coming-of-age drama, to war movie, to heist thriller, but with each step of the journey, it grows bleaker, more violent, more grotesque, more nihilistic, more New York. There are few genre pleasures to be had here: It’s a movie about people who increasingly feel they have no future and find themselves in a world whose devastation reflects their own hopelessness. —BE

57.

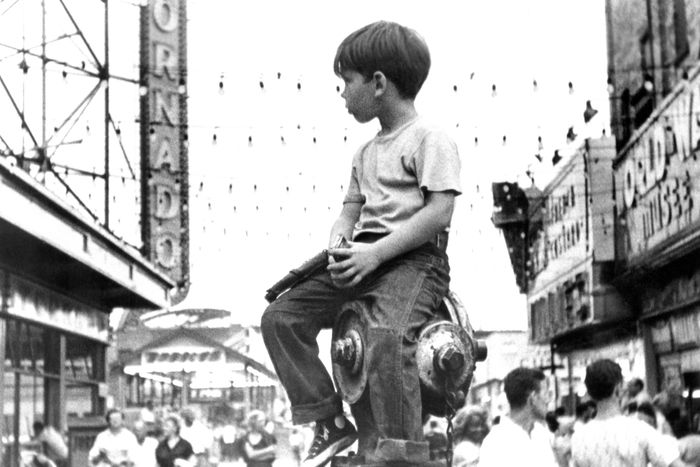

Little Fugitive (Ruth Orkin, Ray Ashley, Morris Engel; 1953)

Morris Engel shot this landmark 1953 indie on the sly using a camera that was strapped to his body so that passersby would be less inclined to notice what he was doing. The result is that Little Fugitive is both a fiction film about two Brooklyn brothers and a snapshot of Coney Island in the ’50s, thrumming with New Yorkers of all stripes and incomes trying to snatch a bit of accessible beach vacation to themselves, even if it’s only for a day. It’s enchanting as an act of sideways documentary, but it’s also a terrific film about the interior lives of children. Joey Norton (Richie Andrusco, in his first and only movie role) believes he killed his brother in what was actually a gag, but can’t help but get pulled in by the offerings of the neighborhood he runs away to. Who could resist the world of pony rides and arcades, a paradise just a subway ride away? —AW

56.

The Landlord (Hal Ashby, 1970)

A person could argue The Last Detail should be Hal Ashby’s entry on this list, but remember that only a few scenes with those drunken, vulgar sailors are set here in town. The Landlord, the editor turned director’s first film, plays in a similar sandbox to John G. Avildson’s Joe and Miloš Forman’s Taking Off, which all take a jaundiced look at privileged white youth whose plunges into social consciousness don’t go as expected. Beau Bridges stars as a Long Island rich kid who acquires a building in “the slums” (Park Slope, don’t laugh) and moves in with plans to clear everyone out, including Pearl Bailey and a young Louis Gossett Jr. Naturally he falls in love (with Diana Sands) and begins the process of opening his eyes. Lee Grant was nominated for an Oscar as the country club mom, Robert Klein has a quick scene in blackface, and the music by one of the era’s quintessential appropriative white artists, Al Kooper, could not be more perfect. The screenplay by Bill Gunn, adapted from a novel by Kristin Hunter, who were both Black, makes for a richer authenticity than was common in widely released movies at the time. —JH

55.

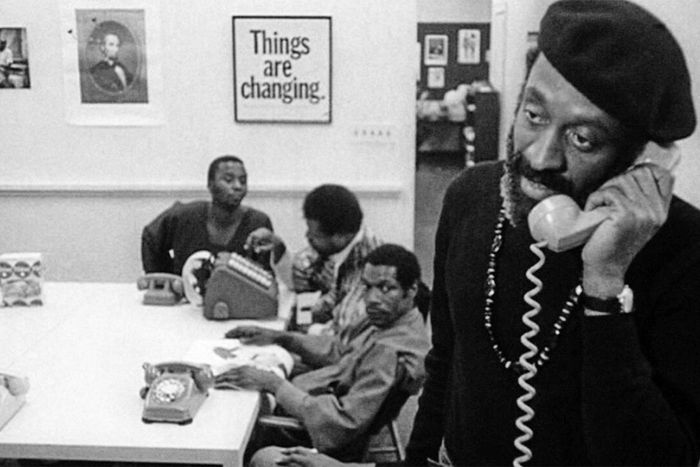

Putney Swope (Robert Downey Sr., 1969)

A do-it-yourself satirist and cinematic prankster, Robert Downey Sr. was a mainstay of the New York underground in 1969 with his freewheeling, experimental patchwork films. But with this incredibly cutting, shot-on-a-dime Madison Avenue satire — which, since it bothered to tell a story, was downright conventional compared to his earlier work — he became something of an institution. The movie follows Putney, the only Black board member of a big advertising firm who winds up unexpectedly in charge after the chairman suddenly drops dead. He immediately transforms it into an all-Black company that tries to do business with integrity, with chaotic results. Along the way, the film comments on everything from the hypermilitarization of society, to the commodification of the counterculture, to the splintering of the civil-rights movement, to both the relentless selling of sex and America’s inherent puritanism. Back in 1969, it felt genuinely timely; today, it feels stupefyingly prophetic. —BE

54.

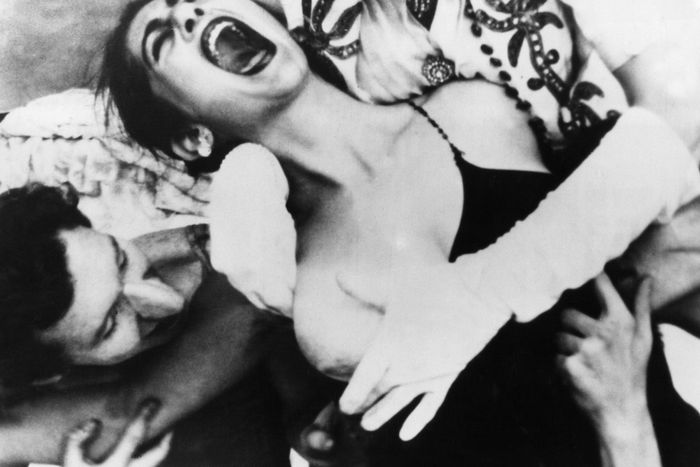

Flaming Creatures (Jack Smith, 1963)

A handheld kaleidoscope of shrieking faces, rolling boobs, and limply spinning dongs, Jack Smith’s 1963 underground cause célèbre actually landed some of its exhibitors in jail; filmmaker and avant-garde entrepreneur Jonas Mekas was arrested in 1964 for attempting to show it at the Lower East Side’s New Bowery Theater, in a now-infamous case that pit obscenity laws against freedom of expression. The film itself is spellbinding, impenetrable, and disturbing: Filled with heavily made-up figures who look like nightmare mockeries of Hollywood starlets, it starts off as a cheapozoid satire of commodification before devolving into a raucous earthquake-orgy of fucking and shrieking. You’ve never seen anything like it — and you never will, which is sort of the point. Shot on decaying film stock, intended for constant revision, and screened in underground venues, the movie feels as ephemeral as the often-transient community from which it emerged. —BE

53.

When Harry Met Sally (Rob Reiner, 1989)

The idea that “men and women can’t be friends because the sex part always gets in the way,” may be incorrect, but When Harry Met Sally is still one of the greatest rom-coms ever made because of the way it mixes genuine warmth with an acerbic New York City sensibility — brought to you courtesy of two consummate New Yorkers, writer Nora Ephron and director Rob Reiner. A lot of love stories use New York backdrops to add a cosmopolitan allure to a film. When Harry Met Sally make the city’s landmarks feel forever intertwined with this movie: the Washington Square Park archway where a young Sally drops off Harry after their disastrous road trip from Chicago to New York; the stroll along Central Park West where the two reconnect and Harry advocates for combining the obituaries and the real-estate section; the visit to the Temple of Dendur at the Met where Harry notes, “You know, I have a theory that hieroglyphics are really a comic strip about an ancient character named Sphinxy”; the meal at Katz’s Deli where Sally fakes an orgasm and, in a cameo, Reiner’s mother famously says, “I’ll have what she’s having.” And of course, that New Year’s Eve party, filmed inside the Puck Building, where Harry professes his love for Sally. It may take Harry and Sally a while to realize they want to spend the rest of their lives with each other, yet they’d long known they wanted to spend the time with New York. —JC

52.

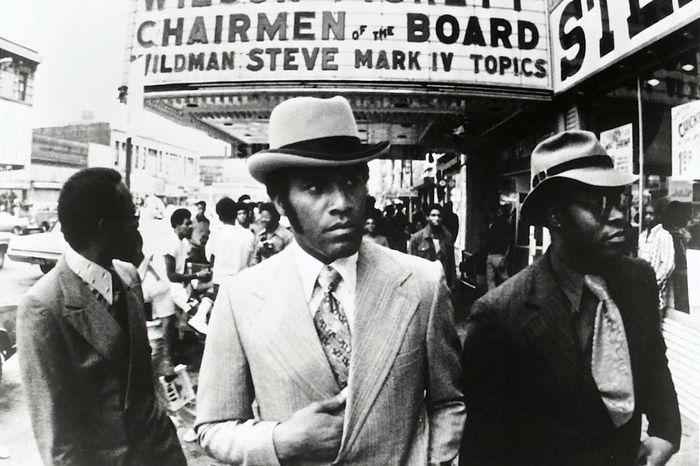

Shaft (Gordon Parks, 1971)

A drum-tight collaboration between co-screenwriter Ernest Tidyman (adapting his own novel) and magazine photographer turned director Gordon Parks, Shaft remains the epitome of New York badassery. The opening credits sequence certified the movie’s rock-solid confidence in its ability to entertain: consisting of nothing more than inventively composed shots of star Richard Roundtree sauntering through Times Square while Isaac Hayes’s soon-to-be-Oscar-winning theme hypes “the Black private dick who’s a sex machine to all the chicks,” it immerses you in the world and mind-set of John Shaft, who — like Humphrey Bogart’s Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe — has a moral code but is beholden to no man, group, institution, or ideology. Somehow this brazenly of-its-time movie has aged as elegantly as Shaft’s leather jacket. A lot of it comes back to the imaginative empathy of Tidyman, who told The New York Times that he wanted to write Shaft as “a Black hero who thinks of himself as a human being, but who uses his Black rage as one of his resources, along with intelligence and courage.” —MZS

51.

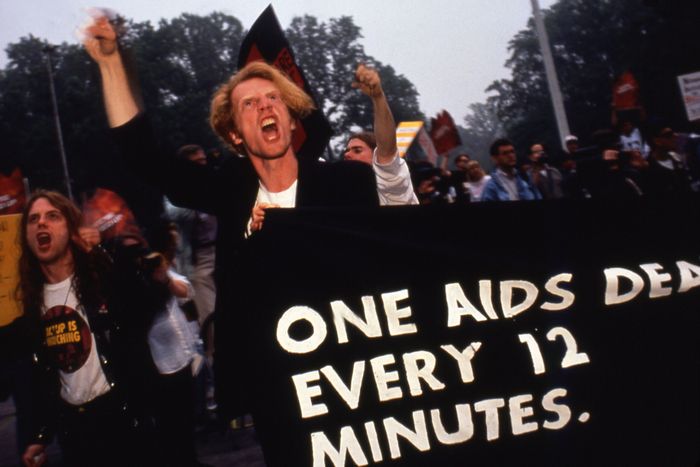

How to Survive a Plague (David France, 2012)

“It’s like living in a war,” Peter Staley explains, early in David France’s documentary. “All around me, friends are dropping dead.” That feeling of hopelessness, fear, and dread was inescapable as the AIDS crisis tore through New York’s LGTBQ+ community in the 1980s and 1990s. So the city’s activists turned that angst into rage, forming ACT-UP and mounting protests at City Hall, city hospitals, churches, and other public spaces. France draws upon a wealth of contemporaneous (and thrilling) video documentation of those actions — it’s like we’re participants, listening in on the strategy sessions, out there on the front lines of a literal life-and-death battle, jeering villains both local (Ed Koch and Cardinal O’Connor) and national (Ronald Reagan and Jesse Helms). Ultimately, Plague reminds us of what the early days of COVID reinforced: that even when we’re the epicenter of an epidemic, New Yorkers will not surrender quietly. —JB

50.

On The Town (Stanley Donen, Gene Kelly; 1949)

You can’t see a sailor on the street during Fleet Week without thinking of it. Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen’s 1949 film of the Comden and Green Broadway extravaganza, with a score for the ages by Leonard Bernstein, is ebullient in that inimitable MGM Technicolor way, and it’s a musical even musical-haters can tolerate. The pace just roars along as the three sailors (Kelly along with Frank Sinatra and Jules Munchin) make their way through 24 hours of World War II shore leave, meeting girls and seeing the sights. There are New York gags about tourists with wildly outdated guidebooks, about intrusive roommates who show up when you’re trying to get busy, about the hopeless act of conversation amid the subway’s roar, about fancy nightclubs with absurd cocktail recipes on the menu. (Also there’s a shot of the Washington Square Arch where your first reaction will likely be My God, it’s so dirty.) The horny comic-relief dialogue from Betty Garrett as the taxi driver, Hildy, is ageless. Only a couple of the stagebound dance sequences fall short — one of them, involving a version of traditional African costume, is absolutely cringey, as are a few other moments — but they pass in a hurry, and you can focus on the travelogue at the movie’s center. And then, as the shore leave ends, the buoyancy breaks down, just for a second: The guys are shipping back out to war, and they might not come back. In even the most exuberant New York story, there lies a hint of tragedy. The Bronx is up and the Battery’s down. —CB

49.

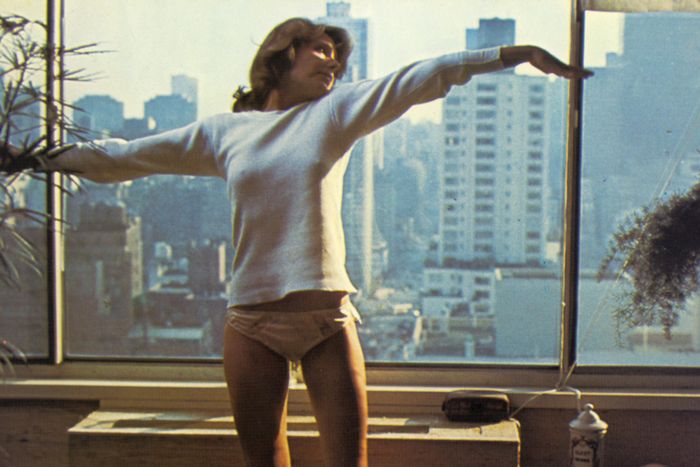

Girlfriends (Claudia Weill, 1978)

Claudia Weill’s 88-minute jewel, pieced together on grant money over three years, has few contemporaries in early independent cinema. Melanie Mayron’s Upper West Side photographer Suzie Weinblatt isn’t a Woody Allen–ish neurotic and she isn’t a “hear me roar” militant. She’s just a young woman who likes her space, knows her self-worth, and keeps on hustling. Though the film touches on romance (and in very unpredictable ways, like with Eli Wallach as a married rabbi over twice her age), dreaming about Prince Charming is just a fleeting thought. That’s remarkable in a film about a single woman today, let alone the mid-’70s. Suzie’s best friend, Anne, has married and moved upstate, and while the film is too nuanced to present it as a death sentence, it is shown as a kind of warning. There’s some great footage of Soho galleries here, and some extraordinary costuming choices. Also: Bob Balaban practicing his Italian with a box of Manischewitz matzos behind him. You can’t fake that kind of authenticity. —JH

48.

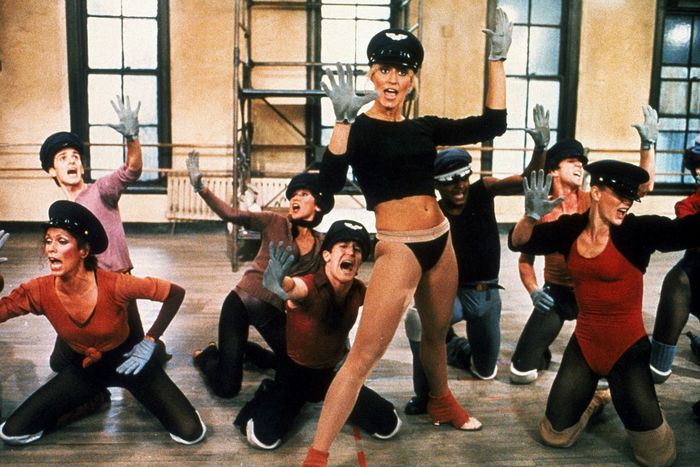

All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979)

One top of being one of the all-time great 1970s New York movies, Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical musical fantasia is a rare film that’s about New York filmmaking in the ’70s. Its main character, hard-drinking, pill-popping, womanizing choreographer Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider), is simultaneously directing a Broadway musical comedy that he loathes and trying to rescue his biopic about a self-destructive comedian (modeled on Fosse’s Lenny Bruce biopic Lenny, which, like All that Jazz, is told in a fragmented, nonlinear style) during late-night reediting sessions at the Brill Building. The cutting, by Alan Heim, is some of the most innovative ever seen in the medium. The photography — by Guiseppe Rotunno, regular director of photography for Fosse’s longtime idol Federico Fellini — alternates quasi-documentary grit for the real-world scenes and creamy voluptuousness for the moments when Gideon recounts and justifies his life to the Angel of Death (Jessica Lange) and fantasizes directing his final exit in the manner of a Fosse stage spectacular. The peerless supporting cast includes Ben Vereen, Leland Palmer, Anne Reinking, Erzebet Foldi, Sandahl Bergman, Cliff Gorman, CCH Pounder, John Lithgow, and — in one of the great one-line cameos — Wallace Shawn as an accountant who figures out that if Joe dies, his latest show could become the first Broadway musical to make a profit without even opening. —MZS

47.

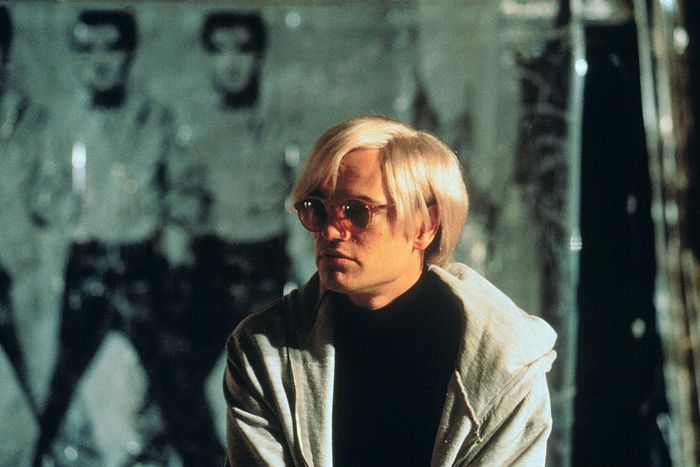

I Shot Andy Warhol (Mary Harron, 1996)

As the feminist writer, hustler, and Warhol Factory gadfly Valerie Solanas, who shot and nearly killed Andy (played beautifully by Jared Harris) in June of 1968, Lili Taylor hunches her shoulders, holds up her head, and charges headlong into a performance that is equal parts inspiring, touching, and terrifying. Her Solanas is a driven, brilliant, deluded woman who seeks to create, and who is bursting with ideas (not all of them good), but finds her street savvy ways are no match for the impenetrable cool of the downtown art-world cognoscenti. Mary Harron’s debut feature offers both a fascinating character study and a lovely recreation of the New York City Warhol scene in all its beauty and shallowness. Crucially, the film also doesn’t judge any of the participants involved: In Harron’s conception, both Warhol and Solanas are tragic-comic figures. —BE

(Jump to Mary Harron’s second film on this list.)

Read about the making of Ciao! Manhattan, set out to capture Warhol’s New York underground ➼

46.

Mother of George (Andrew Dosunmu, 2013)

In his three narrative features to date, Nigerian American director and photographer Andrew Dosunmu has become one of the most exciting chroniclers of New York. Restless City looked at an ambitious, romantic Senegalese immigrant hustling on the margins, while Where Is Kyra? followed a poor, aging Queens woman (Michelle Pfeiffer) impersonating her recently deceased mother in order to keep getting her pension checks. But Dosunmu’s masterpiece is arguably Mother of George, a hypnotic domestic drama set in Brooklyn’s Yoruba community, following a newlywed (Danai Gurira) facing various family and cultural pressures to conceive. Dosunmu and cinematographer Bradford Young place the tense, discomfiting narrative against explosively vibrant colors and settings, channeling the mythic elegance of Luchino Visconti and the pulsating hysteria of Douglas Sirk into something altogether new. —BE

45.

Applause (Rouben Mamoulian, 1929)

“New York’s so big, dirty, and noisy! And your theater: with all those men, and the girls with no clothes on!” So sobs April, newly returned from a Wisconsin convent, to her mother, Kitty Darling, the eternally struggling burlesque dancer determined to keep her daughter away from the allure of the footlights. Broadway director Rouben Mamoulian’s first film — shot on still-used soundstages in Astoria, Queens — is heralded as one of the great early talking pictures. While many of the era planted their actors firmly on an X to ensure clunky equipment could correctly record the dialogue, Applause skitters about through dressing rooms, alleyways, and even, for a moment, the old Penn Station. (A romantic interlude practically dangling off the side of the Brooklyn Bridge is not, however, true location photography.) Though some of the drama may come off as simplistic today, the film’s understanding of the psychological push-pull that performers feel even when “shakin’ for a bunch of Bronx gorillas” will forever remain relevant. —JH

44.

The Producers (Mel Brooks, 1967)

Oddly enough, Mel Brooks, one of the greatest exporters of New York Jewish humor to the world, set most of his movies elsewhere: the Old West, Transylvania, outer space. His first feature, however, is drenched in New York texture and mannerisms. The Broadway producer Max Bialystock is a vulpine, shameless, exuberantly crooked David Merrick type, down on his luck and bilking widows out of their money to finance his deliberately terrible musical Springtime for Hitler. Zero Mostel, who surely knew those kinds of theater-world hangers-on, plays Max so far over the top we can barely see the ground. There is a Times Square brazenness to both the story itself and the telling of it; you can’t really imagine any other comedy culture bold enough to birth the so-bad-it’s-impeccable taste of a hippie Hitler or a swastika-shaped Busby Berkeley top shot. It’s no coincidence that this movie gave us all the expression “When ya got it, flaunt it!” —CB

43.

Light Sleeper (Paul Schrader, 1992)

One of Paul Schrader’s greatest and most underrated films — a story the director claims came to him in a dream, when a drug dealer asked him to make a movie about him — this moody, stylish thriller features Willem Dafoe as a high-end drug dealer (he sells mainly to yuppies throughout the city, though his apartment is in a pre-hypergentrified Chelsea) working for a ruthless boss (Susan Sarandon!) who’s thinking of switching to the cosmetics business. Schrader calls this his “midlife crisis” movie, and that intimate, melancholy feeling of something being irretrievably lost is reflected and expanded by the changing city around the changing characters: The film captures that moment in the early 1990s when the chaotic, rundown New York of the 1970s and ’80s started to become sanitized, sterile, and ossified. —BE

42.

Make Way for Tomorrow (Leo McCarey, 1937)

Before being split up to spend the rest of their lives apart, the elderly couple played by Beulah Bondi and Victor Moore in Make Way for Tomorrow get one magical day in New York that serves as a bittersweet counterbalance to everything that’s come before. Leo McCarey’s Depression-era drama, a predecessor to the housing panic horror underlying Love Is Strange (a title that appears later on this list), is for the most part a slow-motion tragedy about an elderly couple who lose their home and are forced to separate to seek shelter with their grown children, who live in the city or outside it, and who aren’t cruel so much as they are monstrously and relatably inconvenienced by having to rearrange own limited resources. But, as though to make up for the terrible callousness of the modern life it embodies, the city blossoms in front of the couple when they reunite for one last afternoon together, showering them with small kindnesses as they retrace a trip they took half a century earlier on their honeymoon. The grace of strangers makes up for the failures of family, however temporarily, a touch of movie magic that’s also a truth New York is capable of. —AW

41.

Personal Problems (Bill Gunn, 1980)

Writer-director-actor Bill Gunn’s status as a New York City filmmaking institution extends well beyond the Black characters Hollywood expected of him; in screenplay adaptations, he brought to life rich, privileged Wasps (The Landlord) and a poor Jewish couple who wished to work and die with dignity (The Angel Levine). But he did help shatter a kind of two-dimensional Blackness common in movies by specifically creating Black characters who are messy, intelligent, neurotic, jubilant, petty, and, above all, recognizably human. Though Ganja and Hess is the more well known of his films, Personal Problems, a two-part collaboration with the writer Ishmael Reed, feels like Gunn’s dissertation, the culmination of all his ideas about people and New York. It asks “What aspects of Black life have not been given full treatment onscreen?” and then answers the question with a mix of improvisational realism and melodrama (it started as a radio parody of a soap opera). Like much of Gunn’s work, the film keeps viewers from being certain about where the film is leading them, or if the destination will bring closure, but the journey remains one worth taking. Those of us who were around the city at the time of its original release (it was restored and rereleased in 2018) will find amusement in mentions of the now-defunct Korvettes and the tax-free beauty of buying clothes in New Jersey. —Odie Henderson

40.

Shadows (John Cassavetes, 1959)

Though jazz was born in New Orleans, ask your average jazz fan and they’ll agree the form reached its apogee in New York City in 1959. As Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, and Art Blakey’s Moanin’ were recorded and released, hip moviegoers saw the “jazz films” like the Robert Frank–Alfred Leslie–Jack Kerouac collaboration Pull My Daisy, as well as Shadows, John Cassavetes’s lodestar for American independent moviemaking. Cassavetes, who co-led an acting school and was beginning to gain notoriety as a film and television actor, went on Jean Shepherd’s “Night People” radio show and ended up crowdfunding an idea for a low-budget feature about a Black woman (a would-be writer who dated white men) and her two musician brothers. The first attempt to make Shadows relied heavily on improvisation, but Cassavetes started over after an intense rehearsal period. (He even ditched most of an original score by Charles Mingus.) He ended up shooting on the streets of New York City without permits, and a poignant scene at the MoMA’s sculpture garden — predating Jean-Luc Godard’s trip to the Louvre in Bande à Part — is a highlight. —JH

39.

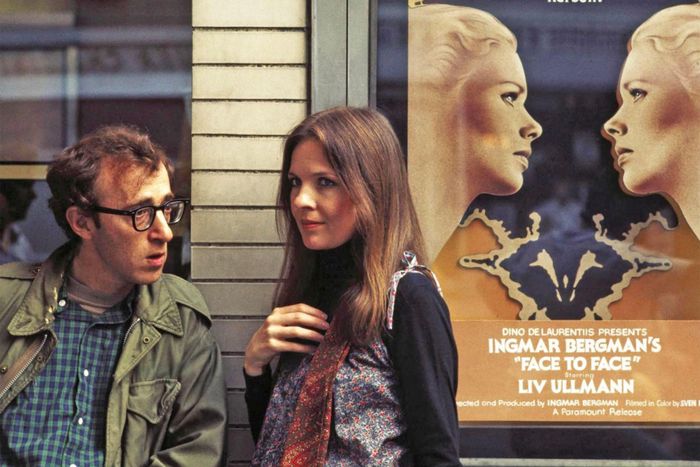

Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977)

It is impossible to overstate Woody Allen’s influence on a certain kind of New York film — that is, the one whose director sees the city as a fundamentally romantic if charmingly infuriating place. But it is undeniable that his films in the past couple of decades have grown increasingly oblivious to their time and place and that the charges that he is a monstrous person grow sturdier in the mind every time Dylan Farrow speaks in public. While most people accept that you cannot judge the work by the person, it’s just about impossible to watch, say, Manhattan — in which the 40ish Allen character dates a high-school student, as he indeed did offscreen — without having those real-life facts curdle your perception. The nebbishy-aggressive-smartass Allen persona that (to a lot of people) once seemed evolved, launching a thousand New York Review of Books personal ads, now comes off less sweetly beta and more just as a jerk. One could make a pretty good case that his darker films, like Crimes and Misdemeanors or Husbands and Wives, are better than Annie Hall. But if what you’re looking for is the modern rom-com aesthetic — one where urbanites wryly joke about bad plumbing and bugs, go for therapy five days a week, take their dates to Central Park, weekend on the East End, and can barely drive a car, let alone parallel park it — it really starts with Annie and Alvy. Also, there is no question, absolutely none, that the scene in the movie-theater line with Marshall McLuhan is a classic. Boy, if life were only like this. —CB

38.

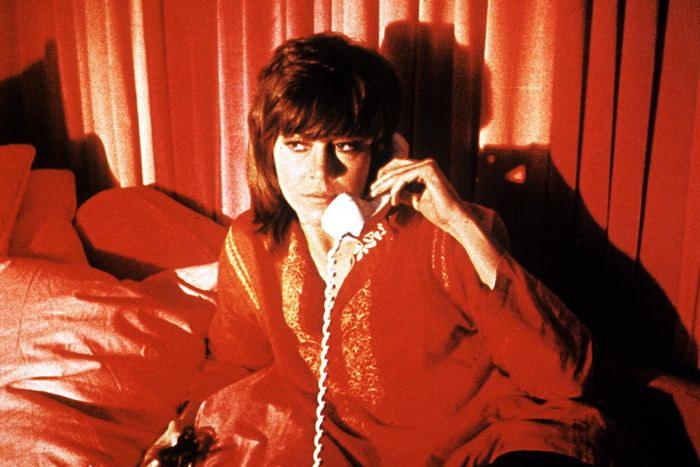

Klute (Alan J. Pakula, 1971)

Few characters in New York cinema are as indelible as Bree Daniels, the hard-edged, tough-talking sex worker at the center of Alan J. Pakula’s unbeatable 1971 thriller. Played with fiery verve by an Oscar-winning Jane Fonda, she puts up the veneer of cold unapproachability required not only by her career but living alone, in the city, in the early 1970s. The screenplay is fairly standard crime pulp — Donald Sutherland’s small-town detective journeys to the big bad city, looking for a client of Bree’s who has gone missing — but that’s not what gives the picture its kick. Director Pakula and cinematographer Gordon Willis fill its sidewalks and high-rises with a sense of dark foreboding and feverish paranoia, an electrifying sense that something menacing lurks around every corner in every dark shadow. —JB

37.

Love Is Strange (Ira Sachs, 2014)

Alfred Molina and John Lithgow are so warmly welcoming as a longtime couple that it takes a while to understand that the film they’re at the center of is actually an unconventional horror story about that most precarious of New York resources: housing. When they lose their beloved Manhattan apartment thanks to a policy of lingering bigotry that embarrasses even those apologetically tasked with implementing it, the two split up to stay with family and friends, pitting affection against the exhaustion of sharing what are already cramped spaces. Ira Sachs’s film is in some ways an homage to Make Way for Tomorrow, but with a distinctively queer outlook at the displacement its main characters face. They’re desperately trying to find a new perch in a city that was provided sanctuary for them and their relationship in most hostile times, but that’s become so economically inhospitable that staying starts to feel impossible. —AW

36.

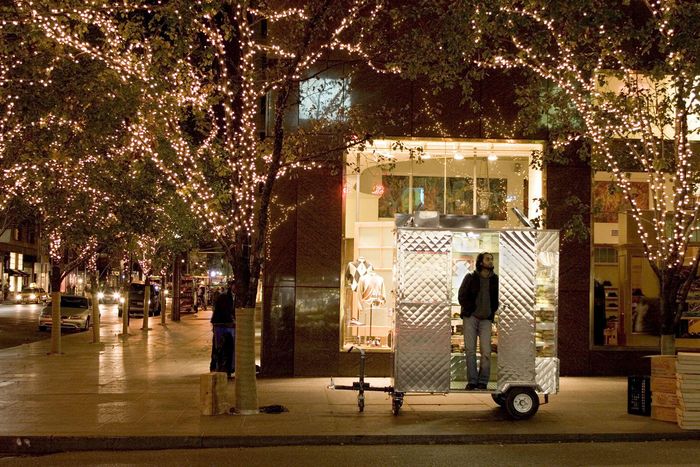

Man Push Cart (Ramin Bahrani, 2005)

Ramin Bahrani’s mesmerizing debut feature follows the day-to-day toil of a Pakistani push-cart vendor as he attempts to make enough money to set up a life for himself and his estranged young son. Throughout, we see snippets of his past — he was briefly a pop star in his home country, but then married and came to the U.S., only to lose his wife — and we start to understand the inner world of this dogged but broken husk of a man. Bahrani shot on the streets of New York, with his star Ahmad Razvi actually pulling and setting up that cart, sometimes even serving doughnuts and coffee to unsuspecting customers. (With this film and its equally stunning follow-up, Chop Shop, the director established himself as one of his generation’s foremost realists.) The city presented in Man Push Cart is instantly familiar but also cruelly anonymous. It’s been stripped of landmarks, of any sense of community. We sense the bone-chilling cold; the gray, dying light; the bustle of the breakfast crowd; and the dry, uninviting solidity of the pastries on offer. And, although 9/11 is never mentioned, we feel the constant tension in the air. Bahrani reminds us that, for all the magic and mystery of New York, it is one of the most forbidding, faceless, unforgiving places on Earth. —BE

35.

Smithereens (Susan Seidelman, 1982)

The film that put Desperately Seeking Susan’s Susan Seidelman on the map, this comedy-drama starring Susan Berman, Brad Rijn (billed as “Brad Rinn”), and punk rocker Richard Hell is an affectionate but clear-eyed look at the remnants of the New York nexus of working-class and middle-class artists and musicians that flourished in the late ’60s and throughout the ’70s. Berman stars as Wren, a young woman from New Jersey who moves into the city to become part of the fading punk-rock scene, represented by Hell’s character, who was in a hot band ten years earlier. Spurred by his fantasies of reinvention, Wren is drawn by (and directed toward) Los Angeles — California standing in for “a new beginning,” as was often the case in this era of American cinema — and is so desperate to start over that she’s willing to compromise, degrade herself, and even commit a crime to raise moving money. Scored by the Feelies and written by Ron Nyswaner, who would be Oscar-nominated in 1994 for his Philadelphia script, this is a great movie about artistic and personal struggle and the toll life extracts on young dreamers. —MZS

34.

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (Rodney Rothman, Peter Ramsey, Bob Persichetti; 2018)

Batman and Superman might have those vague urban stand-ins Gotham and Metropolis, but Spider-Man is the New York superhero, his adventures — particularly his cinematic ones — corresponding to whatever our idea of the city happens to be at that point. (Just look at how Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man films handled our post-9/11 emotional landscape, turning what was once a crime-ridden, one-dimensional comic-book setting into an expression of urban solidarity and resilience.) In telling the story of an Afro-Latin teen from Brooklyn named Miles Morales who takes up the mantle of Spidey with a little help from his interdimensional friends, directors Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, and Rodney Rothman give us a deliriously inventive saga that updates the Spider-mythos for our times, delivering a diverse array of web-slingers who fly in the face of the typically Übermensch-ian hysteria of superhero narratives. Here’s a movie whose eclectic, beautifully patchwork animation style reflects the explosive aesthetic diversity of the city in which it takes place — the rare animated film that feels like its look and style were inspired by New York itself. —BE

33.

The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928)