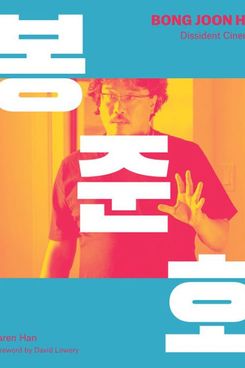

When I was first approached by an editor from the magazine Little White Lies about writing what would become Bong Joon Ho: Dissident Cinema, it took me no time at all to say yes. The pitch was that book — the latest in a series of collaborations between LWL and Abrams Books that has yielded monographs on the Coen brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson, David Fincher, and Sofia Coppola — would cover Bong’s feature films as well as assorted other works (short films and music videos). As a longtime fan of Bong’s work, the chance to write about his films, which defy easy categorization and seem, to me, to be in their own class entirely, was a dream come true.

Bong Joon Ho: Dissident Cinema was released last month, and like the other books in the series, it contains interviews with the subject’s key collaborators. Among those interviewed for my book is the marvelous Tilda Swinton, whose work with Bong — in Snowpiercer and then Okja — manages to be both gloriously over-the-top and subtle, is totally transformative, and marks a creative relationship that extends beyond that of director and actor. “Director Bong is so encouraging and welcoming of these flights of fancy,” she told me during our conversation, which you’ll find partially excerpted below. “He really encourages us to just go there and to not second-guess even the most surreal ideas.”

excerpt from 'bong joon ho: dissident cinema'

Since first appearing in Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio in 1986, Tilda Swinton has established herself as one of the most brilliant and chameleonic actors of our time, amassing a prolific and widely varied body of work as well as the accolades to match — an Academy Award and a BAFTA for her performance in Michael Clayton (2007), a 2013 tribute from the Museum of Modern Art, and a spot on the New York Times list of the greatest actors of the 21st century. Among her most memorable roles are two collaborations (three, if you’re counting characters) with Bong — the harpy-like Minister Mason in Snowpiercer (2014), and the diametrically opposed twins Lucy and Nancy Mirando in Okja (2017), all three ghoulish but still, in a testament to Swinton’s skill, strangely sympathetic.

Do you recall what the first Bong movie you ever saw was?

I remember very, very well. It was The Host. I had just flown into New York and I went to have breakfast with a friend of mine. I went to the bathroom and I was waiting in this little sort of corridor outside the bathroom in this little café in the East Village. And there was a New Yorker magazine lying there, and it was open on a review of The Host that made me want to go and see the film that afternoon, which I did. I remember this beautiful graphic — there was a beautiful illustration of the tentacles of the creature coming out. Anyway, that was my sort of conduit — the messenger that got me into the cinema — and it completely blew me away, of course. Then I just basically watched everything I could. I went full throttle and found everything fairly fast. I even managed to find Barking Dogs Never Bite, which Director Bong is very coy about. I don’t know whether he’s coy about the film, but he’s very coy about anybody saying that they’ve seen the film. I’m a big supporter of the film. But I sort of overdosed on everything I could find. And then I met him in Cannes [in 2011].

He was on what I call the jury next door, and we had breakfast together.

Can I pick up on the point where you say Bong is very coy about Barking Dogs Never Bite? I feel like every interview he’s done where he’s mentioned it, he says, “Please don’t go watch it, it’s very stupid!” Have you talked to him about the film?

I know! Which makes us all want to see it even more! But it’s true. I don’t know if it’s because he made it before he had his own dog, or came to know my dogs, but he’s definitely very coy about it. Sheepish, even.

Do you recall what you first talked about when you got breakfast at Cannes, when you first met?

I think we certainly spent quite a long time talking about the breakfast, ordering the food. We just immediately fell in step. We just liked each other there and then. It helped, of course, that I loved his work so much, but he was so exactly what I hoped he’d be. He was companionable and witty and curious — full of glee and mischief. We just became very close friends that very day.

And he was preparing Snowpiercer, but quite quickly he said to me, “There’s really nothing in Snowpiercer for you.” He talked to me for about 50 minutes about whether or not I should play Claude. He asked me for a while about Claude, after we left Cannes. He kept asking me and I said, “You know what, I’m really longing to work with you, but it’s not that.” And then he went quiet for a few weeks. And then one day he wrote to me … No, I think he’d already sent me the script, just for my interest, and I’d read it and found it fascinating. And he said, “You know Minister Mason, who’s described as the mild-mannered man in the suit — what d’you think about that?” And we just started to make mud pies together.

Did he ever tell you why he thought of that part for you?

No! I wish you’d ask him! No, I don’t, I really don’t.

I find it funny that the character’s original description is of a mild-mannered man in a suit, because in the film, the character is, at least aesthetically, kind of the furthest thing from that. I want to start with Mason’s nose, which you’ve said was something you’ve wanted to do for a while with a character. What was the genesis of that desire?

I think maybe even at that first breakfast I said I’ve always wanted to play a character where their nose is up like that [pushes nose up with her thumb]. I just personally think it’s funny, and clearly you do too. And you could do it very simply and cheaply — you just need a piece of Sellotape. It does something very interesting to your mouth; it makes your eyebrows go up. The whole attitude of the character just suddenly appears. I think I already mentioned that, in theory, before the Mason idea came up — and I think he said, “Well, what would you do with that mild-mannered man in the suit?”

And I said, “Well, first of all I’d do that nose!” I think, in fact I know, that the next step was, he came to Nairn, in Scotland, with [longtime producing partner] Dooho [Choi] and my great friend [costume designer] Catherine George.

We just decided we were going to play with the character; to find Mason. I remember putting a whole bunch of dressing-up clothes in our drawing room. Catherine had brought all sorts of things as well. One of the first things I did was get the Sellotape and put my nose up. And we just played like a bunch of 6-year-olds, really — dressing me up. There was one photograph that Director Bong had produced, which was a photograph that he’d found of a woman who we called the “Parrot Lady.” I’ve no idea who she was. She just looked like a parrot. She was a more naturalistic version of Mason. Mason was an extreme, Hayao Miyazaki version of this woman. She was sort of the first indication. She was slightly hunched, wearing a uniform of some kind. she was a librarian or something. And there was something about her hair, which was cut like that. But then we just took it to the psychedelic level, and we realized we needed to have a fake wig. We didn’t want her to look naturalistic at all. And we started putting uniforms on me and ribbons, and the idea of all the fake medals. This whole thing took about an hour, and I know that because I had a pie in the oven. I said, “Okay, I’m putting the pie in the oven and when it’s ready then we’ll eat lunch.” And by the time the pie was ready we’d kind of got it.

That’s incredible. Did you develop her voice during that session, or did it come later down the line?

I think it came then. This is how it works with Director Bong. He’s so encouraging and welcoming of these flights of fancy. Certainly with me and Catherine, he really encourages us to just go there and to not second-guess even the most surreal ideas, certainly in the work that I’ve made with him to this point. We’ll have various conversations about other things that will have a slightly different caliber, which won’t be so extreme or so grotesque. Because the three portraits that I’ve made with him so far, which are Mason and the two Mirando sisters, have been pretty out there, pretty grotesque — and burlesque, even. So we have plans to make something more naturalistic, and maybe a little less fanning the flames.

That brings us to the characters of Lucy and Nancy. I understand that you were brought onto Okja a lot earlier than you were with Snowpiercer — at the point where they were still working out the script and the story. When did Bong first show you the sketch that he’d done of Okja or tell you what the story was going to be?

We were in Seoul for the premiere of Snowpiercer, and the next morning he was taking us to the airport. Someone else was driving and he was in the front seat, and he leaned over the back and showed me this little drawing. He’d made this little doodle of this little girl standing beside this big pig, and he said, “This is the next film,” and I said, “What the … ” I’ve mentioned Miyazaki before — one of the many strands of the bond we share is a great love of Miyazaki, in particular My Neighbor Totoro. Also Spirited Away — we love those twins, those women who start as monsters and end up as these very sympathetic characters, or godmothers rather. So this very first drawing to me indicated — not in a sort of plagiaristic way, but in a sort of reverential way — that it felt like an homage to something in Miyazaki that we loved.

The characters of Lucy and Nancy, even though their faces are the same, their aesthetic choices are so different. Was there ever a point where you thought they’d look exactly the same, or how did you come up with their respective looks?

Our idea was that they were actually identical, it’s just that one of them has sort of let herself go, whereas the other has spent a lot of money on cosmetics and her hair and all the rest of it. But we didn’t really employ much prosthetic [stuff] with Nancy, the structure of her face hasn’t changed — she’s just got a really difficult haircut and clothes, and maybe hasn’t moisturized as much as Lucy has. The idea was they were actually almost a bit Dorian Gray that Nancy kind of came down from the attic, and Lucy was, you know, the portrait, the public face of Mirando. So in the first section, she’s wearing those training things on her teeth, and then in the next section her teeth have been all straightened and whitened.

I read that there was a specific detail that you came up with for Nancy, which was the idea of her carrying around a neck pillow all the time. Where did that come from?

I don’t know, it was just one of those things. Now, of course, I see them everywhere, not just airports, but everywhere you walk you see people with neck pillows. But for some reason I just thought it was very funny, and we’d never seen it in a film — just somebody walking around with a neck pillow. There’s just something slightly shameless about someone who walks around with a neck pillow, very admirable about someone who goes, “I don’t care who knows I need my neck pillow when I’m on the plane or the bus or whatever.” It’s someone who doesn’t care how it looks, so we felt that was good for her. And her clothes: The whole idea was that she was a big golfer, so she wears golf clothes, whatever those are.

How deep do you go into creating stories for these characters? Because from what I’ve heard and read, Bong doesn’t really give a lot of detail in terms of backstory, or rather he allows the actors to run with it as opposed to spelling it out for you.

I don’t know that I’ve ever done this, really, with anyone else. Everyone I work with I feel like we have a different set of practices and rituals. I’m not sure it’s necessary or even part of the work, but we just have fun thinking about these … not even backstories, but these side stories, rather. We had this whole fantasy about Mason: I kept thinking what Mason’s cabin might be like on the train and what she’s got in there.

You know, my fantasy was — because that wig is so clearly like a hat, we didn’t even glue it down, we just plonked it on my head — and so the idea was that, maybe in her cabin she’s got a wig block and the hat goes on. And so, is she bald underneath? And I was trying to persuade Director Bong to let me lose the wig, for the wig to fall off at one point and you see me bald underneath, but finally we didn’t do that. She does take her teeth out at one point. I also like the fantasy that, who knows whether Mason is a woman or not? I mean, I’m not really sure what Mason is. Mason could be anything. Mason could take off her breasts and hang them up on a body. We just had so much fun thinking about these strange things, and we had all these side stories for the Mirandos as well. But it’s just fun. It would be perfectly easy to get the scenes without them, but it’s just something that we amuse ourselves with.

That leads me to a quote of yours that I really love, wherein you say that you do the work before you come to set, and then you can play in that world. What else is involved in the kind of work that you do prior to filming as these characters?

The work that I’ve done with Bong so far have been these quite broad constructions — they’re not really characters, they’re not really people, they’re sort of … put together? And so there’s an element of a game about it all. I think it’s possible that if we worked, as we plan to, with a different kind of caliber, it may not be like that, it may be much more interior, one may not have these kinds of silly jokes, or not to the same extent. But it’s just like a sort of fancy dress costume really, just enjoying this inner pantomime of these characters, and imagining their other lives. It goes on when we’re shooting as well — it’s just constant silliness. I can’t think of a better way of describing working with Bong when we’re shooting: He wants you to be really free. He works in this disciplined, constructed way, working with his editor beside him. He shows his cut constantly to the people that he’s working with — that may sound like it would be quite constraining, but I find it very freeing because he’ll say, “So this is exactly the way you left the frame in the last bit, and that next bit is the way you enter the frame.”

So you’re free within the bit that you’re just about to do, to fill it however you want. And that precision is, so that sense of play, and that sense of riffing, seems to me to be very much a part of what he’s interested in. He’s interested in all his comrades being very free and into it and enjoying themselves.