What makes for a great cinematic kiss? The kind of kiss that enraptures an audience because they can feel it in their very bones. The kind of kiss that brings to mind young love long past or the need for something fresh and illicit. A great cinematic kiss is predicated on chemistry and characterization, framing and pacing, but ultimately its success rests on the answer to a single question: Is this the kind of kiss you want to have?

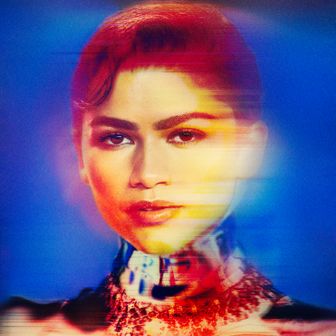

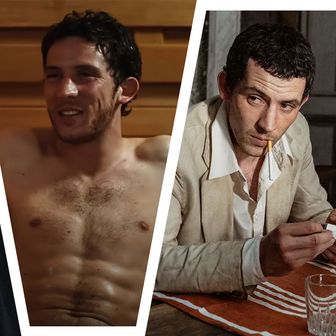

Relatively early in Challengers, director Luca Guadagnino’s peripatetic drama about tennis pros, there’s a kiss — a series of first kisses, really — shared between leading actors Zendaya, Mike Faist, and Josh O’Connor. It takes place 13 years prior to the film’s main timeline. (A fleeting remark about Hillary Clinton’s former presidential campaign overheard on the radio marks the film’s present-ish day as 2019.) Zendaya plays Tashi Duncan, a fiercely intelligent and unapologetically competitive tennis player, who at 18 years old decided to go to Stanford instead of jumping directly into the pros. She speaks of tennis like a lover whose body she studies with the reverence of a priest. Her gaze is meant to read as clear, her voice and posture undaunted. And yet while Zendaya is front and center in the movie’s marketing material, the film’s most important relationship is between Art Donaldson (Faist) and Patrick Zweig (O’Connor), tennis players who have known each other since they were 12-year-old bunkmates at boarding school. The sexual tension between these young men is so thick that Tashi notes she would feel like a homewrecker responding to one or both of their apparent affections for her. “It’s an open relationship,” Patrick counters with a wolfish grin that cuts through the pressure in the boys’ messy, overheated motel room one night, strewn with cigarette ash and half-filled cans of beer.

Now, that kiss. Tashi sits on the motel bed and motions for them both to join her. In a tangle of frantic limbs they land on either side of her. Patrick has already explained that he taught Art how to jerk off, which, until this moment, has been their only physical sexual encounter. Here, Tashi is in control. She teases them with almost-kisses, effervescent touches. Then she turns to Art. Mouth open, eyes closed; hungry with need. Their kiss is tentative before passion takes over. She turns to Patrick, whose desire for her manifests in even deeper kisses and roving hands. The kiss turns three-way thanks to Tashi’s physical encouragement, until she leans back on the bed and lets Art and Patrick sweatily make out on their own as she smirks behind them. The blocking of this moment makes the constitution of the relationship triangle explicit: Tashi’s elemental force in the middle, shaping the reaction these men also have toward themselves and each other. Zendaya leaves them with hard-ons and a proposition: When Art and Patrick go up against each other tomorrow, whoever wins will get her number.

After this scene, the sexual tension between Art and Patrick recurs only as thinly veiled subtext. And this kiss, for all its worth, exemplifies the film’s tragic fault: It teases at a complicated sensuality that the story desperately reaches for but never grasps. Guadagnino continues his tradition of serviceable if not forgettable romances that have enough actorly commitment and precise costuming (in this case by J.W. Anderson) not to feel entirely empty. This isn’t to say his films aren’t worth experiencing. There’s Tilda Swinton in the opulent 2015 film I Am Love, the main quartet in A Bigger Splash has its moments, and I enjoyed Taylor Russell’s nervy-ingenue performance in Bones and All. But I often feel like Guadagnino’s work exemplifies how you can mask mediocrity with the right posturing to garner prestige. We’re all starving for legitimate adult dramas with charismatic performers that neither talk down to the audience nor are skittish about the complexity that comes with being grown. But Challengers plays like an intriguing diversion from all that starvation that ultimately leaves little impression. The details of these people’s lives and their interiorities are so thinly drawn they feel more like beautiful ideas crashing into one another and leaving little messes that are too easy to clean up.

In 2019, the trio’s respective lives have taken on jagged new contours. Tashi, after a devastating college knee injury, can no longer play tennis, so she has channeled her desires into the career of her husband, Art, the father of their now 5-year-old daughter. They’re a power couple in the tennis world, navigating their early 30s with the force of their great wealth, articulated bluntly in a building-size luxury-car ad starring them both. But it’s clear by this point that Art doesn’t have Tashi’s edge, nor does he have Patrick’s scrappy selfishness. It’s honestly hard to glean how much, if at all, Art enjoys tennis because he comes across as so downtrodden at this stage in his life. When and why did he disengage? That’s never illuminated. We never learn much about how Tashi feels about her body post-accident or after having a child.

Speaking of Patrick, for reasons that also remain murky, he’s living out of his car and playing Challenger tennis, the second tier of game within the sport, for the money. Class is a force rippling underneath the surface of Guadagnino’s story, which hints at the fact that Patrick comes from family money but, like everyone and everything else, his wealth and sudden lack thereof are merely ideas that are never explored so much as gestured at. The Challenger arena is where Art and Patrick cross paths again. Tashi schedules Art for a Challenger match to bolster his resolve and confidence ahead of the U.S. Open, and since Challenger competitors don’t find out who their opponent is until closer to the date of their match, his reunion with Patrick is a surprise. Anger and distrust roil between them immediately. From here, the film volleys between the men’s teenage past and grown-ass present, offering new twists, caveats, and reversals with each flashback. These are mostly hollow turns, however, that don’t quite track with the internal logic of the story — they clash particularly with the arc of Tashi’s feelings for Patrick, which seemingly haven’t cooled since she was a teenager despite the cutting aggression she displays when she sees him in a hotel lobby in the lead-up to the challenger match. In the third act, the haphazard jutting finally begins to add texture to the story, but by then, I had spent too long wondering why writer Justin Kuritzkes and editor Marco Costa had hobbled the film’s structure in a too-obvious homage to the serve and return. (Credit to the flinty, sharp score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, though, which lends the film a tense propulsion that the storytelling itself desperately lacks.)

In the last act of the film, Guadagnino and cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom (who is behind Apichatpong Weerasethakul films like Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives as well as the Suspiria remake and Call Me by Your Name) adjust their approach to the tennis matches. Before Art and Patrick’s Challenger match, the tennis scenes are shot traditionally — they show the entirety of the characters’ bodies as well as the faces in the audience shifting back and forth with each serve. They’re not wholly unenthusiastic but the scenes rely considerably on the actors to sell the intensity of the match; you need Tashi screaming “Come on!” to feel the strain. But in the final match between the former friends, point-of-view shots are introduced — from Art’s and Patrick’s vantages and that of the tennis ball. During one part of their match, the camera is positioned from below, as if the court floor is glass, while we watch these men leap. I imagine this is meant to bring as much ragged athleticism as it is renewed intimacy to the filmmaking. It’s entertaining, barely, and jarring — too much too late. The movie’s tennis appeal feels like the movie’s sex appeal: There are a lot of moments of intense foreplay and near climaxes, but the film is mostly predicated on teasing the audience rather than getting it off. The body is incidental to the hothouse psychological games these characters are playing on or off the court.

It’s undeniable that Zendaya is a star. O’Connor (whom I was recently bored by in La Chimera) and Faist (who gained other people’s attention for his turn in Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story remake) turn in perfectly fine performances, but they remain in a star’s shadow — not just any star but one of the few Black actor-producers given real opportunity and industry support. It isn’t that Zendaya is the better actor among them; it’s that she’s treated as the film’s gravitational force even though she’s playing a sketch of a woman. On red carpets ahead of the premiere, Zendaya (in collaboration with stylist Law Roach) has put on the kind of silkened armor and saucy charm necessary for the role of Tashi, bringing an edge, maturity, and boldness to her star image in the process whether wearing a custom blush-pink Jacquemus dress or all-white Calvin Klein suiting. It’s a shame these moments that so beguile us on press tours cannot be found in her screen performances. The charisma and intensity just aren’t there. In Challengers, Zendaya doesn’t believably play a woman in her 30s who, with a 5-year-old daughter, is defined by an intelligence that allows her to shape the world to fit her desires. When Art tells her he loves her during a crucial conversation about his career, Tashi looks at him with a curious expression somewhere between understanding and pity before she responds, “I know.” Such a moment should hit like a gut punch. Instead, it dissipates upon arrival, like smoke rising in the air. The deadpan delivery feels less an intentional choice than an act of habit. That may work in the HBO series Euphoria, but here it is a reminder of how limited she is as a film actor. Like the film Challengers itself, Zendaya is a star who still operates on the surface of things.

More on Challengers

- The Death of the Classic Film Score

- Why the Oscars Ignored Challengers

- The Challengers Score Should Be Played at the Club