Denis Villeneuve’s two Dune films are bookended by Zendaya’s face. It’s her voice as the Fremen warrior Chani that you see and hear in the opening flash-forward of the first movie, introducing viewers to the universe of 10191 wherein the indigenous warriors of the desert planet Arrakis are battling the evil Harkonnen family. And it’s Zendaya’s face you see at the end of the second Dune film, after her lover, Paul Atreides, scion of House Atreides, the man she trained in the ways of the desert, has thrown Chani over for another woman, the galactic emperor’s daughter, in order to protect his family’s bloodline through marriage. The final scene of the second Dune is an overt nod to the end of The Godfather but with a twist. Francis Coppola’s gangster epic ends with ascendant Mafia don Michael Corleone shutting a door in the face of his wife, Kay, played by Diane Keaton, visually declaring that this is a world of men over which women hold no sway. Villeneuve’s film upends that reading by following Chani beyond her baleful, wounded reaction, into the desert, where she climbs a dune and prepares to ride one of the planet’s gigantic sandworms. The final shot of the film isn’t of the approaching worm but of Zendaya, exhibiting a mix of hurt, anger, and raw determination.

That Villeneuve chose to bookend the first two chapters of a science-fiction epic with closeups of an actress’s face is a testament to how sneakily effective Zendaya has become as a performer and how much her presence means onscreen. Born and raised in Oakland, California, she is the daughter of the former manager of the Shakespeare Theater in Orinda. She performed in hip-hop- and Hawaiian-dance troupes growing up before landing the recurring role of Rocky on the Disney Channel musical-comedy series Shake It Up. It’s hard to imagine anybody watching Zendaya during her Disney Channel days and thinking, She’ll be a huge movie star in a few years. She was funny, likable, and nailed whatever assignment she was given. But she was rarely at the center of the stories.

Everything changed with the expressionist HBO teen soap Euphoria. Creator-writer-director Sam Levinson cast her as teenage drug addict and sometime narrator Rue Bennett, who’s in love with a trans girl named Jules (Hunter Schafer). It was here that Zendaya first displayed that movie-star trick of getting you to care about a character, no matter how much she lied to people or degraded herself. The series was controversial for its explicit sex, violence, and drug use as well as for its creator’s alleged tendency for excessive nudity (notably, Zendaya is apparently the only female cast member who has never done nudity because her contract forbids it), but it was a hit for HBO and became a launching pad to stardom for its cast. Ever since, Zendaya has starred in some of the most talked-about zeitgeist culture of the last five years, reaching the point actors like Julia Roberts were at 30 years ago, when the projects that cast them would give her a little music montage of the star trying on clothes or mastering a skill that was less about moving the story forward than announcing, “Look at who we got!”

Crucially, Zendaya herself has displayed an icon’s instinct for self-presentation offscreen — for making a statement without words, letting her clothes, pose, and vibe connect with onlookers. Her collaboration with her stylist, Law Roach, is an ongoing show in itself, more reminiscent of the self-presentational instincts of contemporary music stars like Beyoncé and Lady Gaga than the co-stars photographed alongside her in publicity shots. Every red carpet outfit is calculated for maximum shareability on social media. She has an instinct for old-Hollywood glamor and for “deep cut” references that congratulate film history-conscious viewers on their ability to spot a reference — the “robot suit” she wore to the Dune: Part Two premiere was a collaboration between Mugler and Jean-Jacques Urcun modeled on Maria, the Maschinenmensch in Metropolis, adding Villeneuve’s film to the pantheon by implication.

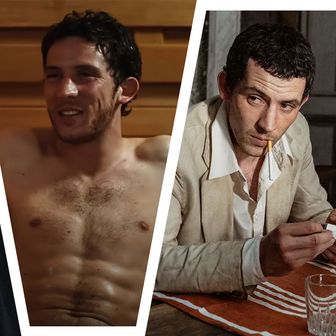

Luca Guadagnino’s forthcoming sports drama Challengers will be the project that puts her over the top, as both a serious actress and a brand. It casts Zendaya as a former tennis prodigy named Tashi whose career is cut short by an injury; she remakes herself as the manager of her good-natured and loyal husband, Art (Mike Faist), who is one leg of a love triangle, the other being Patrick (Josh O’Connor), a scruffy, self-destructive tennis hustler who lives out of his car and rent-free in Tashi’s heart. Guadagnino uses Zendaya’s expressions as a compass, telling us where these three relentless characters are in relation to each other. It combines the in-your-face physical and emotional ferocity of an R-rated sports drama like Raging Bull or Warrior with an old-fashioned plot about two guys obsessed with the same girl that’s straight out of a Turner Classic Movies staple like The Philadelphia Story or Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. There’s also a sort of meta layer in watching it. Onscreen, the two men are fighting over Tashi, but like so many movies built around the charisma of their stars, Challengers is also a film about how people can’t help being in love with Zendaya. The poster certifies this: It’s an empowered riff on the one-sheet for Stanley Kubrick’s film of Lolita, framing Tashi’s cool, confident face in tight close-up behind purple sunglasses. Art and Patrick are reflected, dueling on the court.

Zendaya has never been what some would call a “chameleonic” actress and (so far) doesn’t seem interested in being one. She doesn’t gain weight, put on prosthetics, do an accent, or otherwise foreground the mechanics. She’s a gestural, reactive performer; she’s been a dancer and musician almost as long as she’s been an actor, and that’s a big component of the way she approaches characters. (In the “action” scenes in Euphoria, as Rue gets terrorized by drug dealers and chased all over town on foot, she moves like a regular, awkward teenage girl rather than as somebody who probably has a personal trainer.) As an adult, she has gravitated toward material that’s fun to play, physically demanding, or both, doing performance work that’s slightly outside of her established range, but not so inconceivable that you expect her to fail. And similar to actors like Roberts, Tom Cruise, and Will Smith 30 years ago, Zendaya doesn’t fit the assembly-line, commercial-TV-approved beauty standards of her moment and is more interesting to look at because of it. Cruise had his spectacular yet irregular grin and prominent nose, Smith his high forehead and jug ears, and Roberts her asymmetrical, almost Cubist facial features. Zendaya has a strong jaw, big eyes, an almond-shaped face, and a skinny neck and arms. Her look makes her a perfect runway subject while allowing her to convincingly play a desert warrior, a teenage junkie, a circus performer, a famous film director’s young trophy girl friend, and a professional tennis player with equal persuasiveness.

Just as important, there’s nothing about her that’s passive, even when she’s cast in a pretty straightforward “girlfriend” role (which is arguably the case in the Spider-Man and Dune movies). There’s a coiled ferocity that complicates and belies her outward presentation of waifish international glamor. Her acting is technically assured but never cold or mechanical. She’s got such a strong work ethic that you never catch her doing anything that doesn’t serve the material, but at the same time, you can sense her drive, her hunger to become one of the all-time greats, even when the camera is treating her as a beautiful object. Imagine Audrey Hepburn with the spirit of a Game of Thrones royal. Challengers is the ultimate example to date of what has become a distinctively Zendaya screen energy. When she raises up her racket hand to serve, you believe she could break your nose with the force of her swing and also that her character is driven, after all these years, by diverted rage at having the world and losing it.

Whether we’re watching her in flashback, winding up to serve against an opponent, or making out with Art and Patrick (and watching them make out with each other) on a narrow bed in a sort of power-trip tease, Zendaya always withholds, through silence, or through expressions that can mean more than one thing at the same time without settling on just one of them. She leaves you wanting more, or wanting to complete the idea, which is how you know you’re seeing a star. In the scene where all three make out with each other, for instance, you could read Tashi’s confidence and avidity as an “older than she seems,” almost femme fatale-type presentation; or as that of a prodigy who grew up in public around mostly adults and felt the need to pretend she always was one; or as the manifestation of experiences (perhaps damage) we don’t know about yet; or a Joker-like force who’s just looking to sow chaos. Any reading seems valid and none are unsupported by Zendaya’s choices in the scene.

The layering works because of Zendaya’s blend of excitement and detachment. She’s always committed to her characters but also seems to stand apart from and scrutinize them as an observer herself. I have a take on this person, and I wonder what yours is? She’s specific but not a micromanager of the audience’s judgments and feelings. On Euphoria, especially, you could see yourself in Rue, even when her character was trapped in situations you’d rather not even think about, much less participate in. She mastered the high-as-a-kite person’s inappropriately big “That’s fucked up!” laugh at weird or scary things — the laugh of a person who feels like she’s watching something happen on TV, not to herself.

In some ways, though, Euphoria was the most lived-in character Zendaya has ever played. Part of this was due to the nature of serialized television, where we watch characters grow and change, mess up and backslide over episodes and seasons. But it was also in part because Zendaya was close in age to Rue when the show started (she was 21, Rue 17). She’s now at that point in her career where she’s playing both teens and fully grown adults. In 2020, Zendaya reunited with Euphoria creator Sam Levinson on Malcolm & Marie, in which she played Marie, the long-suffering wife of a movie director. The film, a misbegotten pandemic project in the vein of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, seemed to be more about airing the filmmaker’s grievances against critics than creating fully believable characters. Zendaya alone saved the movie from spiraling into its creator’s navel. As Marie, she was a one-woman bullshit detector, communicating the audience’s frustration with Malcolm, a director who based the heroine of his latest film on his wife’s struggle with drug addiction and wouldn’t admit it was a thinly veiled version of her, sparking an all-night argument about Malcolm’s narcissism and the state of their relationship. The peak of Zendaya’s performance is a moment where Malcolm, who’s wolfing down a bowl of macaroni and cheese she made for him, insists the character is based not just on her but on “people.” “What people?,” she asks. “A lot of different people,” he replies. She shakes her head at him, her head swiveling on her neck like a sink faucet in its mount, and mid-move, she says, quietly, “Hmmm.” It’s so brief that it barely registers, but there are years of disappointment in that syllable.

Malcolm & Marie was also the most-panned role of Zendaya’s career. Many felt she was miscast as someone older and more mature than her years and that she didn’t have the innate gravitas to compensate for that, as, say, Lauren Bacall did in her debut film To Have and Have Not, when she was a 20-year-old convincingly holding the screen against a 45-year-old Humphrey Bogart. “She doesn’t carry the weight of real emotion and complication — whether she’s quietly crying, stripped down in a bath, or shouting obscenities,” Angelica Jade Bastién wrote in her review of the film. This line of criticism will likely continue with Challengers, where she alternates between playing a college student and a mother/manager in her early 30s. Zendaya, of course, is actually in her late 20s now, but she still seems more comfortable playing the teen prodigy incarnation of the character than the bitter older version.

Of course, she also continues to play characters increasingly younger than herself — in the Spider-Man movies and on Euphoria, a high-school show filled with actors who are now ten to 15 years older than their characters. Perhaps some ingenue residue clings to her despite her attempts to shake it off. That’s another way in which she’s reminiscent of Cruise, Roberts, and Smith, who were so strongly identified with the youthful go-getter energy they exuded early in their careers that they didn’t seem fully credible as adults until they were deep into their 30s (or in Cruise’s case, his 40s).

Still, they were nearly always just what the project needed, even if you were worried about miscasting beforehand. Modern audiences have become so fixated on every element of a character matching who the actor is that in some ways we’ve lost the understanding of what stardom can mean, and allow for. When you love somebody and feel with them, you tend to rationalize away what doesn’t work. That’s how audiences ended up buying Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and James Dean as embittered elders in the latter sections of the western epic Giant, even though they were obviously the same beautiful young actors we met in the earlier scenes, but with gray stuff in their hair. In the reverse, it’s how audiences bought Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci as guys in their 20s in the middle section of Goodfellas even though they were both clearly in their late 40s. We will give a star anything if we enjoy being around them, if we are given the space to find ourselves in their impassive stares and unexpected silences. As for Zendaya, I think I would probably believe her in anything if the script and direction were good, because she has forged that pact with the audience that says, “We’re agreed that we’re in this together, pretending, so give me this one.” Most important of all, when she’s really cooking, you don’t catch her acting: She’s just your girl up there, moving through the story and making you want to root for her.

More on zendaya

- Move Over, Meechee: Zendaya Is Now Shrek’s Daughter

- Christopher Nolan to Bring The Odyssey to the Big Screen

- Sam Levinson Still Likes Working With Pop Stars