This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

This piece was originally published on February 8, 2024. We are republishing it to mark the news of Oh, Mary! heading to Broadway this summer. Read more about the news here.

It’s 28 degrees outside in mid-January, and Cole Escola is leading me around Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery in search of the gravestone of an actress-producer who died in 1873. “My lips are gone,” Escola tells me as they clutch their phone with gloveless hands. We’re spinning around, attempting and failing to follow directions from a combination of Google Maps, Apple Maps, and findagrave.com. They assume the voice of a prototypical audiobook narrator: “Two faggots walk into a cemetery …”

We’re looking for the grave of Laura Keene, who was performing in Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., when Abraham Lincoln was shot in 1865. Escola chose to bring me to Keene’s grave in honor of their debut play, Oh, Mary!, which they wrote and star in as Mary Todd Lincoln in the days leading up to the assassination of her husband. Keene told people she had rushed into Lincoln’s box with a glass of water and cradled the dying president’s head in her arms. Some scholars have since theorized that she lied about this melodramatic moment, which would make her a spiritual predecessor of Oh, Mary! One of the show’s central tenets is that the truth matters less than a worthwhile fabrication.

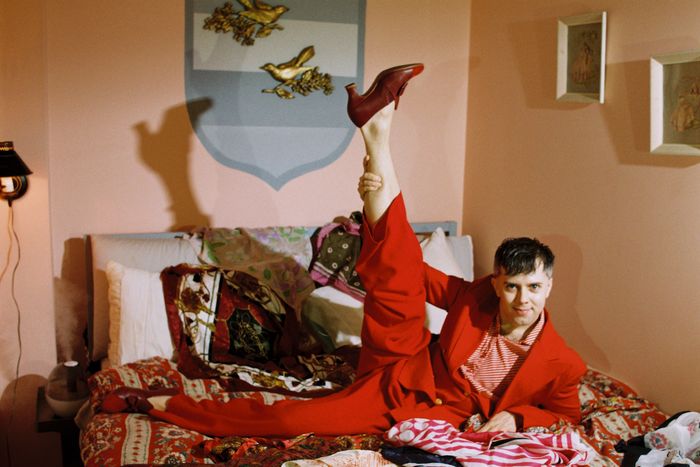

The germ of Oh, Mary! began with an email Escola sent themselves in 2009 asking what it would be like “if Abe’s assassination wasn’t such a bad thing for Mary.” From there, they did little to no research. In Oh, Mary!’s telling of history, Mary is a former cabaret star longing to get back to her previous work rather than remain in the gilded cage of the White House. (She drinks paint thinner to cope with this, is forced by her husband to vomit it up, then drinks the vomit.) Escola’s Mary is conniving, mean, and loud. She schemes and plots her way back to the cabaret stage by throwing people down stairs, verbally destroying an acting coach, and screaming at her husband. Escola calls Mary a “Miss Piggy type” — she’s akin to an actress who wants to play Juliet but is meant to play the nurse. Even as her behavior grows deranged, Escola manages to get audiences so engrossed in Mary’s headspace that they come to cheer on Abe’s death right along with her.

Escola, 37, is primarily known as a comedian and TV actor. They gained attention in 2008 for YouTube videos in which they played characters both based on real people and of their own imagination: a loopy diva like Bernadette Peters, the depressed busybody Joyce Conner, a mom in an orange-juice commercial so dedicated to her children that it drives her to violence. They’ve been a regular on Search Party and Difficult People, and in both they brought the idea of the “demon twink” to its fully villainous conclusion. In all venues, their work feels somehow of a piece with classic gay artistry — they get referred to as “camp” a lot, a descriptor they see as “not lazy, but not thorough” — and specific to them. More recently, they’ve released longer narrative productions like Our Home Out West and Pee Pee Manor on YouTube, in which their characters often speak in a luxurious legato with an occasional chop of a phrase that cuts through everything around it. In Pee Pee Manor, after the main character is warned by townsfolk through ominous monologues to not move into her new house owing to its previous owners’ unnatural deaths, she quips, “Accidents happen. Look at Pearl Harbor.” Their works are exquisitely rendered artifacts of stupidity with a handmade quality that makes them feel less like the increasingly polished queer media we’ve been inundated with of late, from Matthew López’s The Inheritance to Andrew Haigh’s All of Us Strangers, and more like part of an exciting new generation of slapdash queerness indebted to John Waters alongside Josh Sharp and Aaron Jackson’s Dicks: The Musical.

Escola was born in Clatskanie, Oregon, a town of 1,700 people. When they were 5 years old, their family moved out of a trailer, away from Escola’s father, and in with their grandmother, who was their primary parent for a while. She was a grandma’s grandma — “Gray perm, rice pudding, doilies; she made clothes, and she could knit and crochet and bake” — and accepted Escola’s latent fagginess without fuss, buying them their first Barbie without any curiosity about why they would want it. Other family members would encourage their femininity in a way that felt too pointed: “It was always, ‘You can play with this if you want.’ And that felt like, ‘Well, now I feel like I shouldn’t be playing with it because you’re making it seem odd.’”

They realized they were nonbinary (without the label) upon seeing the book cover for A Child Called “It” when they were 10. The memoir, by Dave Pelzer, is about a boy who is dehumanized and abused by his parents, but Escola didn’t read it, so the title seemed positive. “I remember thinking, like, Oh my God, that’s me. I’m not a boy. I’m not a girl. I’m it,” they recall. “I had two friends, and we would use the it pronoun to describe each other. Not in public or anything but just in private. Between us. We called ourselves ‘the Its.’” When they came out as nonbinary in 2020, they almost used it as their pronoun of choice but opted against it because “I was like, Don’t be extra annoying.”

If they knew they were an it at 10, they knew they were poor much earlier. “I hated my family so much for being white trash,” they say, though Escola didn’t call them that at the time. The first divas they worshipped were homemakers, like their grandma, but skewed upper-middle class — beginning with Kanga from Winnie-the-Pooh; progressing to Mrs. Potts, who lasted through age 8; then landing on Martha Stewart. Over one summer when they were a tween, they would regularly stay up until 5 a.m. to watch episodes of Martha Stewart Living. They spent their birthday money on Christmas decorations and idolized wealthy, sophisticated characters like Christine Baranski’s Maryann Thorpe on Cybill, realizing, as many gays have before them, that if they couldn’t be cosmopolitan through money, they would have to do it through culture.

When they were 16, they moved in with their cousin to go to a high school in Longview, Washington, that had a drama program. (Subconsciously, the move was also due to the fact that they felt like they’d be able to come out in a new place.) Escola had learned to be funny in late middle school and early high school because it meant they got bullied less. “As long as there’s going to be attention on me, I might as well command it myself,” they say. They hated school but ended up enrolling at Marymount Manhattan College in New York in order to follow their boyfriend at the time: “I was like, I need to be near him or kill myself.” The two broke up before school started, but Escola still made the move in 2005. After their freshman year, they dropped out because they couldn’t take out any more loans without a guarantor.

The following year and a half in New York was not good. Escola was, in no particular order, “suicidal, bulimic, lonely, and depressed.” They got a job at the Scholastic Bookstore, where they alternately worked as a cashier, hosted birthday parties, and, sometimes for events, dressed up as Clifford the Big Red Dog. One day, their friend sent Escola a pantsuit that made them wonder if they could pass as an older woman. “I dressed up in it, and I had this fake-fur coat, and I did horrible frosted makeup and spiked my hair,” they recall. Escola gave her a name — Joyce Conner — and took a walk in character around the Upper East Side. “Because I was suicidal at that time, I thought, Wouldn’t it be funny if I was having my thoughts, but as her? ‘I’ve got to kill myself Saturday.’ What if this busybody woman was thinking about her suicide as if it was a lunch she was having on Sunday?” Suddenly, even though they were still thinking about suicide, they felt happy.

Soon after, a friend of Escola’s made a student film about Joyce, which Escola showed to Dan Fishback, a playwright and performer they were seeing at the time. Fishback encouraged Escola to perform in Bushwick as the character, inviting them to open for anti-folk bands, a genre that began in the 1980s as a way to rebel against the glossiness and rigidity of mainstream folk music. “Joyce was a big part of the Brooklyn anti-folk scene for about six months in 2008,” Escola says. That year, they posted their first video as Joyce to YouTube (“Joyce Conner Survives the Heat,” in which Joyce says she attempted to kill herself a few months prior before realizing the pills she swallowed were vitamin-D supplements). Over the next few years, they built their audience more consistently; they performed live, doing character sets and cabaret, both on their own and as part of Bridget Everett’s 2013 show Rock Bottom, in which they played a fetus. By 2015, they were cast on Difficult People, and, in 2017, they became a recurring guest on At Home With Amy Sedaris. Oh, Mary! is Escola’s first full-scale live production, involving multiple sets, four other actors (including Conrad Ricamora, fresh off leading the Broadway production of Here Lies Love, as Abraham Lincoln), and a director, Sam Pinkleton, who just worked as the choreographer for Stephen Sondheim’s final musical, Here We Are.

As we trek through the cemetery fields, veering off the paths, the conversation turns back to divas. Escola loves pre-Code movies, and they have a particular fascination with Barbara Stanwyck — “You can’t catch her acting” — whose mother, Kathryn Ann Stevens, is also buried in Green-Wood. When they lived nearby, Escola would come to the cemetery just to visit Stevens’s grave. The first time they traveled to Europe, they went to Marlene Dietrich’s burial site in Berlin and the apartment in Paris where she died. “I love Dietrich,” they say. “I didn’t like when she wore suits.” We share an obsession with Elaine Stritch. “Her talent aside, she represents this golden age of Broadway and New York — the sort of New York that I dreamed of but I never could be a part of when I was a kid.”

Escola’s relationship with audiences is complicated: “I’m scared of them. I hate them. I resent them. I look down on them. I need them.” In 2016, Julio Torres invited them to perform their first live comedy set on a lineup at Williamsburg venue. They hated it. “You have three people before you who are doing stand-up that’s very conversational. Then I come onstage, and all of a sudden there’s a fourth wall and I’m pulling the wig out,” they explain. “I can feel the audience go, Ugh.” Growing up, their personality (sincere, feminine, loud) was considered obnoxious by family members and peers alike. “My biggest fear and biggest belief about myself,” they say, “is that I’m really annoying.”

But, in Oh, Mary!, they’ve designed a role in which annoyance is the goal. Escola is in total control of the stage as Mary Todd Lincoln. The show is a pastiche of the melodramas Escola loves — they call themselves “a maudlin old queen” — with all the screaming that entails. It’s a subtly tricky part: Because Mary is so impulsive, even a flicker of Escola anticipating her next act would ruin the joke; her mania is most thrilling when the audience doesn’t know what’s coming next. But Escola appears entirely in the moment, letting the audience into Mary’s thought process so that it is rapt because of not only their words but their face. After Mary drinks that bucket of vomited-up paint thinner, Escola lays their whole body back in their seat with the self-satisfied smile of someone who just eked out a battle win in the midst of a difficult war. It brings down the house.

Finally, we arrive at Keene’s grave, where one nearly decayed flower is already resting. We remove the plastic from our Trader Joe’s bouquet of yellow roses — chosen because they were the flowers at Escola’s grandmother’s funeral — and place them down. “Please don’t let the ghosts of Abraham and Mary ruin my show,” Escola implores Keene. “Please protect me from bad reviews. And I hope you’re proud. Love you.”

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 for free, anonymous support and resources.