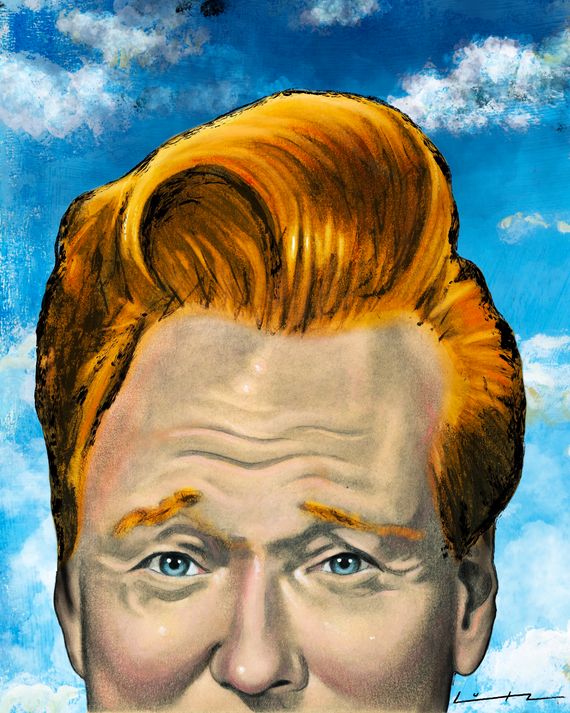

The first time I interviewed Conan O’Brien, it was the winter of 1994 and he had just finished taping an episode of Late Night. He had been a talk-show host for all of six months, with barely 100 episodes under his belt, and things weren’t going great. Most of the boomer critics at the time couldn’t stand David Letterman’s 30-year-old replacement, ratings were so-so, and rumors were rampant that NBC was already looking to bail.

When O’Brien and I talked at his tiny 30 Rock office that night — he was sprawled casually on a small sofa, sometimes strumming his trusty guitar — he seemed quietly confident things were going to be okay. “I never thought this was going to happen overnight, that I was going to take over this time slot and everyone was going to hoist me on their shoulders after my first show,” he told me. “This is going to take a long time. The only thing I can do is to get a core audience and build out from there.”

The last time I interviewed Conan O’Brien was earlier this month, on June 9. He called me from his home in Southern California a few hours after taping his 4,359th episode of a late-night TV show. We have had several of these formal conversations over the intervening three decades, usually as he was marking a milestone such as wrapping up Late Night after 16 years, or taking over as host of The Tonight Show, or launching an eponymous basic-cable talker after NBC famously screwed him over (and he told them to shove it). Our most recent discussion was prompted by something particularly momentous: After a nearly 11-year run on TBS, Conan signs off on June 24. The finale will also mark O’Brien’s exit from the nightly talk-show rat race, though importantly not the end of his hosting career. He has already signed a deal to do a weekly variety series for HBO Max, the exact format of which has yet to be determined. Having fought so hard to succeed in television, O’Brien, at age 58, has no desire to stop filling screens with his particular brand of comedy — though he is clearly ready to move on to the next phase of his career.

During our nearly 90-minute conversation, O’Brien expressed plenty of pride but little nostalgia for the days when, as he put it, he would “take a bullet” for his show, when nothing was more important than proving he was worthy of being part of that small pantheon of comedians entrusted with a late-night program. But what hasn’t changed is O’Brien’s desire to keep pushing himself, to find new ways to keep audiences — and himself — invested in his comedy. Giving up a nightly talk show in favor of a weekly show is as much about reinvigoration as it is abandoning the grind. In that way, O’Brien is approaching his next venture with the same philosophy he adapted when he took on Late Night all those many years ago.

“I didn’t do this to have people look at me and say, ‘Oh, that’s him,’ or to get more money,” he said back in 1994. “I did this because I really wanted to see whoever got this slot really try to do something with it.”

Hello, Conan O’Brien! It’s our once-every-seven-years phone call.

We’re like cicadas: We grow underground and then reemerge and talk to each other about late-night TV and comedy, and then go back underground.

Exactly. How are you doing?

I’m doing really well, actually. Doing great. We’re getting live audiences back next week, and that just … I mean, that just makes me want to cry. I’m looking forward to people again so much. So I’m good.

Very soon, you’re not going to have the prospect of a nightly show to look forward to — or maybe to dread — for the first time in a long while, except maybe for that brief moment after The Tonight Show. But really, this is the first time since Bill Clinton was president that a nightly show hasn’t been in your future. Where’s your head?

You know, people use the word gratitude a lot when they’re talking about crystals and healing. I have felt an enormous amount of gratitude that I’ve been allowed to do this for so long. As you know, when I took over the Late Night show, there were a lot of people who thought, This guy shouldn’t be here, and they weren’t wrong. My story is an unusual show-business story of someone getting such a big job at such a crucial time and people saying constantly that I wouldn’t last two days or three days or four days. I started just after Johnny Carson retired, and he’d done 30 years. And I realize that it’s been 28 [since Late Night With Conan O’Brien premiered], and I am feeling good about stopping the night-to-night. I still want to make comedy, and I still want to make funny stuff. But the night-in, night-out rhythm that started for me in September of 1993 is kind of grueling. I’m feeling like I’ve done that — I did it as best as I could — and while I still have some gas in the tank, I’d like to try a few other things.

I cannot tell you how I will feel on that last night. I’m sure I’ll feel sadness and some pretty strong emotions. But I think the overriding emotion is going to be gratitude that all of this happened. When I got started in comedy in 1985, someone asked me what I dreamed about, and I said I dreamed about having a body of work. People can like what I do or not like what I do, but Jesus, there’s a body of work there, and I’m really proud of a lot of it.

You’ve definitely done a lot over three decades.

We’ve been going back over it, and I’ve got to say, there’s chunks of it I don’t even remember. I watch it and I go, Okay, that’s cool, that’s neat. I can’t believe we did that. I can’t believe I jumped through a pane of glass and fell three stories to do that. So I think that’s mostly where I am — feeling that I’m ready to do the next thing. I love making stuff. I’m always going to want to make stuff. Long after anyone wants to see my stuff, I’ll want to make stuff. But the night-in, night-out, “Hello, welcome, it’s Monday,” “Hello, it’s Tuesday,” “Hi, it’s Wednesday” — I’ve done what I can do with that format.

What led to you realize that you’d reached your limit of making the sort of almost disposable comedy that’s part and parcel of a nightly show?

It’s two things. First, the travel shows, because I feel like I’m able to work differently; we’re really able to craft something. I’m able to go to Ghana, to Armenia, or to Korea and actually go up to the line between North and South Korea with Steven Yeun and shoot comedy there. It felt different night-in, night-out, where you’re trying to make that show’s deadline. I think, for many years, that was thrilling, and I was addicted to it. Really addicted to it.

What happens is, over time as you get older, you start craving different experiences. Those travel shows made me feel like, This is fantastic. I’m physically traveling around the world, meeting incredible people, making comedy that we’d show to live audiences, and they would really laugh hard. And it felt like we were able to craft them a little more and really work on them and think about them. I became, in a weird way, almost like when I was working on The Simpsons and we would really craft an episode and think about it. With the travel shows, even though we only shoot them over a period of a couple of days, we were able to do a lot of research beforehand and put a lot of thought into it, and I felt like I was 30 years old again, having a new experience.

The other thing was the podcast. I’m having interviews with all these fantastic people, and the conversations can go on for an hour, sometimes longer. We can take really strange flights of fancy, and we can really take turns that I didn’t expect before the podcast started. I started to realize, Wow, there’s all these different ways to make stuff now that are using muscles I haven’t really been able to use. Because for 28 years in late night, you talk to someone, you do six minutes, you break, music, then you come back, you do another seven or eight minutes, you’re looking for the funny line to get out. I’ve loved it, but I really do want to make sure that, whatever time I have left in my life to make comedy, I’m changing it up and challenging myself as much as possible. So this just felt like the right time. I don’t think I’m going to wake up the next day and think, Shit, I wish I could do another week. It feels like it’s time to move on to the next phase, whatever that is.

You announced that you’d be cutting the show to 30 minutes per night back in May 2018, and that kicked in at the start of 2019. You seemed reinvigorated by the new format, and there was good critical reaction. But then, barely a year later, the pandemic blew things up again. Do you think COVID maybe sped up the decision to give up the nightly gig?

It’s possible. I wouldn’t say, “Oh, it was the pandemic.” But you bring up a good point. I think if there had been no pandemic, it’s possible we would have done a little more time here before seeking out a new format on HBO Max. I can’t speak for the other late-night hosts, but, like everybody, we tried hard to innovate and make it something interesting. But the lack of that energy, that audience, and also the restrictions of Zoom and things like that, over time I think it took some of the fun out of doing this. Anybody who got to keep working during the pandemic is a very lucky person, so I’m not complaining at all. But there is a certain energy that these shows thrive on, and I think the pandemic made it a lot harder to get that energy flowing at times. It’s possible the last 15 months could have sped things up by a year.

But you were headed to this decision anyway.

I remember, before the pandemic, feeling that we needed to keep trying to innovate and change in order to freshen things up and to keep it exciting. It’s why we went to half an hour; it’s why we tried to strip it down. It helped get us out of what I call “the lines on the highway.” When you’ve been riding for miles and miles and you just keep looking at the lines on the highway, you can go into a trance and not even be aware that you’re driving 65 miles per hour. I’m just trying to get the word out that if you see me on the highway, get out of the way. I’m probably unaware that I’m driving. [Laughs.]

But for me, even if I’m not youthful anymore, my comedy is youthful. I’ve always had a very silly, energetic approach to comedy, and so I can’t fake that. So we were definitely making a lot of changes to try and keep myself completely engaged and giddy and excited, and it worked for a while, but then the pandemic certainly doesn’t help. While I don’t think it changed the timetable much, it’s possible that it accelerated things to a degree and made this final date pushed up a little bit.

How do you view the time from the start of Late Night in 1993 until now? Is it one long continuum of shows, just with different formats? Or are there more distinct eras in your late-night career?

The first three years of Late Night was one experience, which felt like being in a street fight just to stay alive. [Laughs.] The first three years of Late Night felt like that sequence in Indiana Jones when he’s on the truck and he climbs in the window and punches the bad guy out, but then the bad guy punches him out the window and he goes completely under the truck, climbs over the back side, climbs on top of the truck and then comes back through the windshield and punches that guy off a cliff. That’s the best visual representation I have for the first three years of the Late Night show.

Then you switch into this other era, the last 16 years of Late Night. Then you get to the Tonight Show period, which is brief — shockingly brief. And then you get into the tour that we took, which was very intense, and then into the TBS show. What is interesting is that, all along, there are different feelings as you go and different looks. But the approach and the comedy philosophy are always the same, which is trying to make things that are silly. The comedy I really like is evergreen. My favorite comedy is not topical; my favorite comedy is making stuff where you don’t need to know, Wait, who’s Joe Manchin, and how does West Virginia play into it? I appreciate that comedy, and I think it can be very brilliantly done. But it’s not what I do.

So I look at the whole thing as this hobbitlike quest where I have my little band of other hobbits, and we’re on this journey to find funny, silly things — images, characters, moments, remotes, travel pieces, puppets, papier-mâché birds, animation. It is a 28-year journey to find silly things that we hope amuse other people. So if you really think about it … whether it’s Late Night or The Tonight Show or Conan, it’s all the same idea.

If I’m remembering right, you had a couple of options after you left NBC. You probably could have done a show for Fox or maybe syndication. It was a little surprising when you chose TBS. What made you choose it?

It surprised people because I think the media, more than humans — [laughs] I’m making it sound like the media isn’t human!

We aren’t, actually.

I think more than civilians, the media likes a late-night war. It’s kind of easy to understand, and you can have take after take on who’s up and who’s down. I was caught up in all that. It was actually nice for a long time at NBC at Late Night because I wasn’t caught up in all that. We were on at 12:30 at night, and once we got to the point where we were stable and doing well, we were allowed to play, and we had a lot of freedom. And then I went through the whole Tonight Show craziness. After all of that, I remembered feeling, Okay, what are we going to do now? There was a chance we could go to Fox, but it was problematic because I don’t think Fox had the affiliates lined up so we might have had to start out only being carried partially by affiliates. That wasn’t too appealing.

Then I had a meeting with [then–Turner Entertainment chief] Steve Koonin. He was wearing a raincoat that Columbo would wear. It was raining in L.A., and he looked rumpled and he was not slick. He came in, and he said, “All I can promise you is that we’re going to make you our priority, and we’re going to let you do whatever it is you want to do because we don’t know how to make a late-night show.” He had so much emotional intelligence, and he’s such a genuinely kind person. I thought, Okay, maybe this won’t sound cool to people, but I know I have to go somewhere where I can take my people, we’ll be taken care of, and we get to set up our own little workshop and get to work and make the kind of toys we like to make. And here we are, 11 years later. Steve always kept his word, and everyone since Steve did the same thing. I can’t say enough good things about TBS. I don’t know what would have happened if we had gone to Fox. Maybe it would all have worked out, but I’m not eager to get in a time machine and find out.

I think the pressure at Fox would have been a lot more intense than at TBS. The whole TV universe has changed so much. Everyone’s ratings are dramatically lower than they used to be.

It’s really changed so much. And I have to say, it’s the natural state of things as you get older to get grumpy and think, Well, it’s not the way it was in my day! And I have found the opposite to be true, which is: I keep looking at how much the internet has helped perpetuate comedy. I meet people all the time who say, “Oh my God, last night I was watching Conan remotes, and I watched this one,” and I’ll go, Wait a minute, this is from 1997, and this person is 18 and they watched it last night on YouTube. I find that to be exhilarating.

I mean, it used to be that Johnny Carson would do an anniversary show once a year, and he and Ed McMahon would wear tuxedos and take a look at some clips from the last year. Now, there are certain clips that are out there, certain moments that people see, and they just keep bouncing around and people watch them like they just happened. I was outside the theater where we shoot our show about two months ago, and a guy stopped his truck, pulled over, rolled down the window, and said, “Hey, Conan, caught you last night with Wilt Chamberlain! That was hilarious and fantastic!” And I thought, When did I talk to Wilt Chamberlain? I looked it up, and he was on the show in 1997 and I think he died in 2000.

And that’s how a lot of folks, especially younger folks, are absorbing the comedy you make now, right? You can’t see it in the Nielsen numbers, but people watch.

You can ask what is late-night TV now because so many people don’t watch it late at night. So many people just want to see the clips that are distributed, and they’ll watch it the next day or the day after that. In 1993, if you weren’t up at 12:35 and saw the show, you missed it. It was gone. But it’s so nice now that if you are making comedy and some of it’s worthwhile, that stuff tends to get around. That’s the blessing of this modern era: We’re in a world where any late-night host who stumbles upon something really good, it’s going to get out there. So this business of who’s beating who in the horse race at 11:30 doesn’t feel as important as what people are doing, which is the way it should be.

The South Korea trip and the response people there had to you also had to be a milestone.

Yeah, and it was really fun because it was just a discovery. When I arrived at the airport in Seoul, they said, “There’s some people out there.” And it was just insane. I just couldn’t stop laughing because, at the time, I thought I was long in the tooth in late night. I just love these Jed Clampett moments where you aimlessly fire at the ground with your old shotgun and oil comes shooting out. We found that there’s whoever sees it on the linear show on TBS, but then there’s this whole other life that things have that’s much more powerful, that people pick up on the internet and it bounces all around. I’ve been all over the world several times, and people who don’t even speak English want to talk to me about Kevin Hart and Ice Cube. It’s amazing.

A few years ago, you told Terry Gross that “fear and intensity” drove a lot of what you did in life from your teens right through your 40s but that now your goal was to challenge yourself to do things that took you out of your comfort zone. You’re clearly doing that by leaving the security of a nightly show, but has the intensity changed all that much?

What I was saying to Terry Gross is that there is a period of your life — this was the case for me, and I think it was the case for other people I’ve talked to as well — where there is something that you almost have no control over. This is how I best describe it: I didn’t decide to be ambitious. Something was pushing me. And it was important to me, once I found comedy, to keep at it and at it and at it, and to think about it a lot and, first as a writer and then as a performer, to really try to think about, What do I like? What feels right to me? What am I really proud of? God, that felt good; how can I get that feeling again? Now can I get that again? Now can I get that again?

I won’t lie: When you get married and you start having kids and your kids are growing up and you have a good share of success, that drive gets blunted a bit; I’m not the guy I was when I was 22 or 32 or 42. Something does change. And I am happier now than I was at any other period in my life. They’ve actually done studies where they say people do tend to get happier later on. I think that’s because you spend so much time fighting your demons and trying to prove yourself and then you wake up at some point and you realize, It went as well as I possibly could have imagined it to go. And I am so happy to spend time now with my kids, who are so hilarious and smart, and my wife, who’s so hilarious and smart.

I’m still looking for the camaraderie of making comedy with really funny people, and I’m still hungry for that. I mean, in ’93 I’d have taken a bullet in the chest for that late-night show, you know? You could have had assassins beat me with pipes, and I still would have crawled out there and done that show because I had something to prove to myself, or, as Freud would say, to my dad or whoever. That defined this whole chunk of my career. This last period, especially at TBS, we’ve worked hard and pushed ourselves, but we’ve also had a lot of fun. And I’m proud of a lot of the work, and things are not life-and-death like they used to be. I have no interest in revisiting that period; I do not romanticize it. I mean, you knew me back then, and that was … [long sigh] I’m glad to have made it to this, I’ll say that.

You were definitely ambitious then, and it was clear when I first met you in 1993 or 1994 how seriously you took everything. But you also seemed grounded then in a way you don’t always see with comics or entertainers who are starting out. And honestly, you still seem that way. Maybe it was a very good act, I don’t know.

Where I got really lucky is my parents and my siblings. I come from really good people, and I come from people — and it might be an Irish trait — but in a good way, they don’t give a shit. They’re proud of me, but none of that has anything to do with my being a son or a brother. I come from a family where there’s no escaping who you are. There is no becoming a different person or putting on airs or saying, “Hey, by the way, in case you didn’t notice, I’ve won some Emmys, so I think maybe it’s time people started giving me my due around here.” If I ever said anything like that, the first response would be to laugh really hard in my face, and the second response would be to throw me out the second-story kitchen window of our house on Kennard Road in Brookline. Something that was ground into me at a very young age that has carried me even through those dark years when I was desperate [or] ambitious: I never forgot that I am the third kid of six and where I’m from and how I’m supposed to behave. So that I cannot take credit for.

I remember talking to one of your siblings and one of your parents the day NBC announced you as the new host of Late Night. I was a freelance writer for the Boston Herald, and they had me call your family to find out more about this unknown kid. I think I spoke to your brother Luke.

That’s so funny. I’m not really doing press for this. I’m not looking for a lot of fanfare. I call this the “Irish good-bye,” which you’ve probably heard about. Irish people are there at the party, they’re fun, people are laughing and then at one point, you look over and they’re just gone because Irish people hate to say good-bye. I want to have a lot of fun with the end of this show, and I want people to be laughing and then sort of notice, “Hey, where’d he go?”

You mention Luke. Luke had one of the best quotes about me ever. Someone said to him, “Gee, can you believe Conan’s been working on his show for 28 years?” And Luke said — and he meant it — “You don’t understand. Conan’s been working on this show his entire life.” Luke was talking about the fact that we used to go play stickball across the street with a bunch of other kids from the neighborhood, and all I would do is routines the whole time. I wouldn’t play the fucking game! When it was my turn to bat, I pretended to be a character who’d had trouble with the press. Everything was shtick. So my brother said, “Don’t say he’s been working on this show for 28 years because some of us have been putting up with this bullshit since 1966!” So to me, I heard that and I was like, Yup, he is absolutely right. For good and for ill, he’s absolutely right.

You mentioned earlier how folks still enjoy your older clips, and you absolutely have a ton on your Team Coco website. But what about full episodes of your past shows, particularly from the Late Night era? Will we ever get access to those? Is there a plan?

My agents hate it when I say this, but if someone showed up and said, “Look, you’re not going to make a dime, it all goes to ExxonMobil, but we figured out a way to just show your clips forever into the future on this one place in high def,” I’d just be absolutely delighted. We did a huge undertaking; it took forever, but we went back through all that old stuff to digitize it and put it up there. And that does seem to be the way people consume shows now. I don’t honestly know if there’s an appetite for someone to say, “I want to watch an October 11, 1994, Late Night With Conan O’Brien with special guest David Brenner and Charo.” There might be with real intense TV historians, but I think most people want to see the funny clips. I’m really happy that we were able to work out a way to show that stuff and to get it out there in the right format and everything. That was a white whale I was pursuing for a while, and I was really glad we could work that out.

My brother Neil has VHS cassettes of all of my shows, and I mean up until just a couple of years ago when I finally convinced him that no one does that anymore. If I go to my parents’ house, on each cassette, there’s three-to-four shows. If you used them as bricks, you could build an exact reproduction of the Pentagon in real size. It’s massive, the amount of tape he has.

I disagree with you that there’s not an audience for the full episodes. Maybe there’s not one big enough to work for a big platform, but full episodes of Carson air on Antenna TV and on streaming platforms such as Pluto TV. And you’re a lot more current than Carson.

Oh, wow. It’d be interesting to watch it because the other thing you see is how TV’s rhythm changes.

The one stumbling block would be musical guests. It’s so expensive to get the rights cleared.

Right, that’s the other thing. I mean, God, if we could show the musical guests, I’d be in heaven because there were so many amazing musical performances on Late Night. But you can’t get the clearances. So that’s an issue. We were so naïve and such kids that we’d do a comedy piece and we’d score it with Led Zeppelin and not think another thing about it. So then we’d have to go back and remove “Stairway to Heaven” or the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life.” We didn’t know what the hell we were doing. We’d just think of the perfect tune for that sketch, and we’d do it. And then we started to realize, Ohhh, if we do this again, we’re going to owe Jimmy Page $2.4 million!

I’ll tell you one funny thing. I’ve had the opportunity to hang a couple of times with Sir Paul McCartney. One of the times, we were chatting at a dinner, and somehow we ended up talking about late-night bands and I was talking about my band. I said the band will play a generic tune on the air and then the minute we hit commercial and we’re no longer on the air, it morphs into a Beatles classic for the audience and they go crazy. Then when we come back from commercial, just before the red light comes on again, we morph back into the generic song. And Paul McCartney said, “What do you do that for?” And I said, “So I don’t have to pay you anything!” As I recall, he wasn’t laughing.

So who impresses you in comedy right now?

I have to say, I am blown away by John Wilson. It’s very funny, but it’s also more than that somehow. It’s very human, and that really impresses me. My wife and I have been watching Hacks, and the writing on that show is superb. I mean, the cast, the performances are fantastic. I’m blown away by Jean Smart and Hannah Einbinder. So many people try to depict what it’s like to make comedy, and comedians always love to watch those shows because they hilariously get it wrong. Hacks feels like the closest thing to what it’s like for people who are struggling to think of comedy, what the process is like and working out comedy with someone else. I’ve been really blown away by that show. Every now and then — and this is like a broken record — Steve Coogan comes along and makes another Alan Partridge, and I’ll see it and I’ll go, Oh, he’s just better than other people.

I mean, the list goes on. There’s so much good stuff. There’s more good stuff now than there ever was before, I think. I want to be the opposite of the cranky old man and say that I’m very aware that when I was growing up, there was some funny stuff, but you really had to find it. And when you did find it, like SCTV or Marty Feldman’s summer replacement show or Monty Python on public television, it was nothing short of miraculous. And now I’ll watch Gumball with my kids — I don’t know if you know it, it’s a cartoon — but when my kids were a little younger, they wanted to watch it and it is some of the best comedy writing I’ve seen in years. It’s just fantastic and surreal and creative. My kids are 17 and 15, and if there’s a Gumball on, we’ll still all sit down and watch it because I think that’s brilliant.

There’s so much good stuff everywhere that it’s a little humbling. So many people are out there making really impressive comedy — and not just in the United States but worldwide. There’s that French show about a talent agency, Call My Agent, and I’ll watch that and go, Okay, God, this is great. Have you seen Bo Burnham’s latest? He’s brilliant. And I’m a huge Bill Hader fan. Barry is excellent because it really does walk that line between being very funny and perilous and very sad. Those guys have really walked that line with eerie perfection. I think I’ve now given you many shows.

I know you haven’t really figured out the details of the new show for HBO Max. But do you at least know what you want it to be?

I don’t know exactly what it is. I’ve been talking to the HBO Max people, who’ve been terrific. They’re very nice, and they seem very smart and are great collaborators. I do think that whatever it is, I want to double down on field pieces where I’m out with a camera because I think when we get those right, they’re distinctive. I don’t want to leave and then come back and do a show that feels like we could get this from other places. I’d like to contribute something of worth, and so whatever the next show is, I think we would try and double down on the things that I enjoy — things that I feel, when done well, have some merit. And silliness. I will not be fighting crime.

It probably won’t be with an audience, or will it?

I’m a sucker for an audience, so I will find a way to blend it where maybe I can have [one]. My aim is to have my cake and eat it, too.

Do you think it’ll be at least mid-2022 before you return with the new show? Could it be sooner? Later?

It will definitely be into 2022 before people see anything. I don’t want it to be too long, but I want people to be shocked at how I’ve aged when I show up for the new thing. I can do that pretty quickly, but you’ve got to give me at least six months. But I want it to be upsetting to people what I look like when I reemerge. And I’m going to act like I always have. I’ll act very youthful and impish and foolish, like I’m a 30-year-old who just got his late-night show. But I want my physical appearance to be nothing less than horrifying.

No more beards, though! You talked about that on Stern a few years ago.

No, we’ve done the beard. And once Will Ferrell shaves your beard on TV, you’re not allowed to grow it back.

Speaking of long beards, you interviewed David Letterman on your podcast in 2019. How fun has it been experimenting with that format?

The podcast was a total accident. I’m willing to try things, and somebody said, “You should do a podcast,” and I made fun of the idea. [But I] said “Okay, let’s do a test one,” and I just had a lot of fun. That’s just blossomed into something where, you know, I just got to talk to Obama for an hour and ten minutes. I had Obama on the [TV] show, but that’s very different. There’s an audience, there’s music, there’s “Let’s take a break and we’ll have more.” It’s not the same as being able to sit across a table from someone in a small room with a microphone and shoot the shit and see where it goes.

That’s what I’m in search of: Whatever the medium is, what’s the format where I get to still be a kid? If there’s one message you take away from this, it’s that late-night comedy has kept me childlike, but the trick to that is you have to keep changing it up and keep looking for the next iteration and keep looking for the next format and keep looking for the new outlet. My goal is to just stay a kid. It really is Peter Pan syndrome. I want to stay young and silly at heart, and the way to do that is you’ve got to keep moving. I’m very grateful for 11 years at TBS, but I want to retain that foolishness. It might be that the secret to my pompadour is that it only survives if I’m doing silly stuff that challenges me and makes me giddy. And if I lose track of that, I will just have a very sad comb-over.