This article was originally published on January 12, 2024. At the 2024 Oscars, American Fiction won the award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

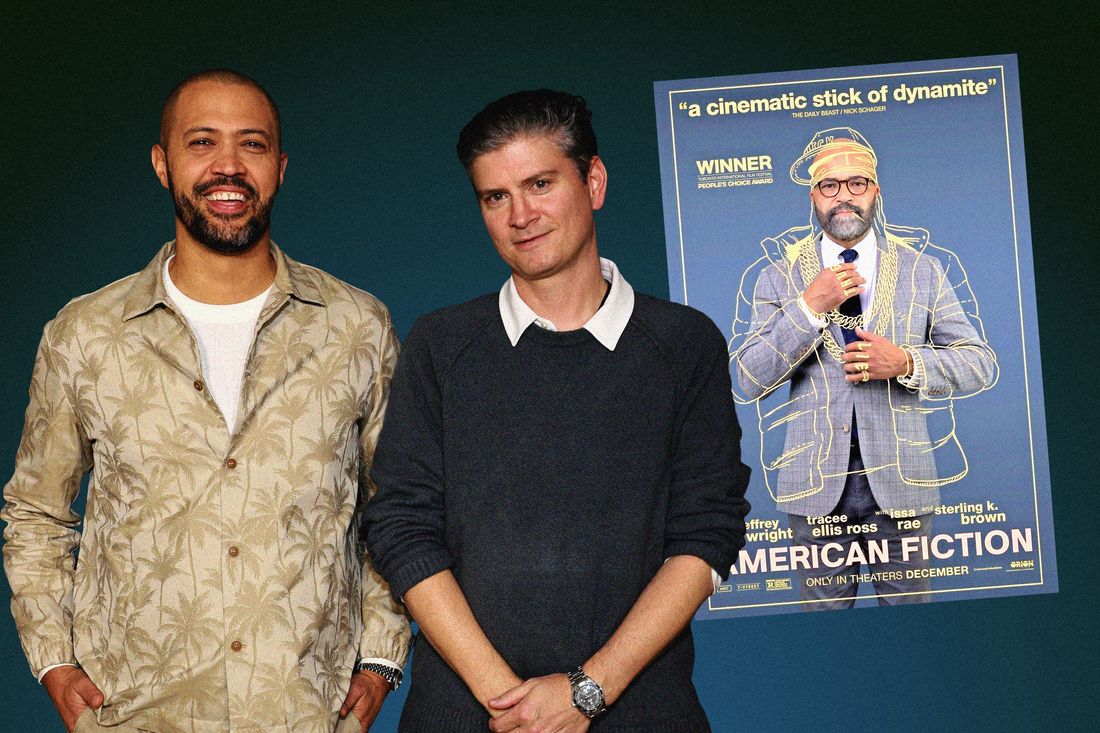

Last November, when Cord Jefferson sat down for an interview at Vulture Festival, his movie American Fiction — which has been nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture — was only just beginning to achieve some of the buzz that made it and its stars a fixture of awards-season nominee lists. Based on the 2001 book Erasure by Percival Everett, American Fiction marks Jefferson’s film directorial debut following stints as a writer for shows such as Watchmen, Station Eleven, and The Good Place. He worked on the lattermost show with its creator, Mike Schur, who was all too happy to join Jefferson at Vulture Fest and play the role of interviewer.

You can read an edited version of their conversation below or watch it here:

MIKE SCHUR: Cord, I have a thesis. It regards you and American Fiction. Over the course of this interview, I’m going to attempt to prove this thesis. At the end, I’ll reveal it, and you can decide if it’s correct.

CORD JEFFERSON: This is wonderful. I’m so happy I asked you to do this because you always make something way more fun than it needs to be.

You were a journalist for a while, and I feel like while you were blogging, you were interested in what journalism could and couldn’t do. Were you thinking about fiction writing during that time?

Yeah. Two of my artistic heroes are Joan Didion and James Baldwin, and it’s not just because I like their writing and work. It’s because to them, what it meant to be a writer was a very big thing. They would write a screenplay, and then a book of essays, and then a novel, and then a piece of journalism. They were the kinds of writers who were like, “Yeah, I can do that.”

And so I thought about writing fiction one day, but it always seemed like I would write novels rather than screenplays, because I didn’t know anybody in entertainment, and if you don’t have access to people who work in the business, then it feels like, I don’t know how to get in there.

I have a visceral memory of looking at books on my mom’s shelf of Gore Vidal or Norman Mailer. They would say “other books by Gore Vidal” and list books of essays and plays and novels and historiographies. I remember thinking, Who are these people who can do all this stuff? The answer is Cord Jefferson.

You become a TV writer post-journalism. I met you when you were on Master of None, which I produced but did not create. If there is a common thread among the shows you’ve worked on, here’s what I think it is: You are drawn to projects that aren’t “one thing.” So Succession, a searing drama that was also maybe the funniest show on TV. Station Eleven: a genre show, but also apocalyptic; tiny and huge at the same time. Watchmen: graphic-novel genre show, but also meditation on the Nixonian era and race and everything else. And The Good Place, where you and I also worked together, a network comedy/moral philosophy.

Meditation on death.

Yeah, slash the afterlife! Is that a coincidence? Or are these the projects you have sought out?

It’s not a coincidence. What connects those projects is that they were all swinging for the fences. There was an ambition to do something that feels at least a little different. By the time I got into TV, the world had so many distractions: Audiences were watching shows and movies less and less, and that was even pre-TikTok. People have asked me what lessons I brought from journalism into other stuff I’ve worked on, and one of the most important lessons, which I apply when I go into any project, is Why now? As a journalist, you approach everything that you’re writing with the question, Why does this make sense in the world for this specific moment? Why should I spend my time and energy on it?

When it came to all these projects, it felt like, Oh, this is timely and relevant and has something to say about the world at present, as opposed to rebooting a TV show just because it used to be popular. I’d rather be working on a grand failure than a mediocre success.

Two of those shows, Station Eleven and Watchmen, are adaptations. The movie you wrote is also an adaptation. I’m currently in the middle of the first adaptation I’ve ever done, so I’m wondering: What do you think about the debt that is owed to the source material?

With Watchmen, we were taking huge departures from the source material. That can be a little dangerous because there are no restrictions, so you can blue sky and go crazy. What Damon [Lindelof, showrunner of Watchmen] used to say to give us structure was, “Does this feel Watchmen or does this not feel Watchmen?” To him, it’s more about whether creative decisions keep with the spirit of the original text rather than the letter of it. That’s how I felt doing Station Eleven and Watchmen, and I brought that to American Fiction. Maybe two-thirds of the movie is vastly different from the book, if not more, but I was always trying to maintain the essence of the original.

I watched No Country for Old Men recently, which I hadn’t seen in years, and it’s perfect. It’s a perfect movie. And then I thought, You know, I haven’t read No Country for Old Men since probably 2006. So I reread it, and it’s just the movie. The movie is the book is the movie.

Really?

It’s shocking. Entire scenes are seemingly just Cormac McCarthy’s words put into Final Draft. It reminded me of when Kenneth Branagh was nominated for an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay for Hamlet, and the whole point was that it was the unabridged Hamlet. He just shot Hamlet and then got nominated for an Oscar! What a heady play! And his Hamlet is great — he made a decision to be 100 percent loyal to the source material, and that was the right call. And then there are Damon and you and the Watchmen team saying, “Our Watchmen is set in Oklahoma City in contemporary America and has all this stuff you could not find a hint of in the source material,” and yet it is also great.

I want to hear about your experience reading Erasure for the first time. It was three to four years ago when you told me about it — you said you loved it and wanted to option it and that I should read it. I did, and had two thoughts. One was, How did this book exist in the world for so long without anyone else telling me? And two was, The idea of adapting this is a home run.

I had a big professional failing in 2020 where I thought I was going to get this TV show on the air and came very close, and then they pulled the plug at the last minute. I was towards the end of the year — a year that was obviously bad for everyone — and I was kind of feeling adrift, not knowing what I wanted to do next, and so I read a review for this book called Interior Chinatown, which referred to it as a satire reminiscent of Percival Everett’s Erasure. I had never heard of Erasure either, and so I bought it. Can you remember the last book you read that felt like it was written specifically for you? That’s how I felt about Erasure.

I do. I won’t say what it is, but I do.

Mein Kampf! We’ll talk about it after!

Come on, man! I don’t want to distract from —

So yeah, Erasure read like it was written just for me: obviously, the issues of what it means to be a Black writer and the expectations and limitations that people put on creatives of color. That resonated with me deeply going back to journalism days. Then there’s stuff I don’t want to spoil, but there’s a sibling dynamic in the book and the film that felt similar to mine. There was an ailing mother in the story, and several years ago I moved home to take care of my ailing mother. There’s an overbearing father figure who kind of looms large in the novel and the film, and I have an overbearing father figure who looms large in mine and my brothers’ lives. There was a lot of overlap to the point it started to feel eerie: “Oh my God, one of the characters lives in Arizona and I’m from Arizona! The book is set in D.C., I used to live in D.C.! Monk lives in L.A. and I’m also living in L.A.!”

It also felt like I could punch above my weight class as far as the themes compared to the amount of money I needed to make the film. It wasn’t, I need $50 million for my first movie, because there’s no way somebody would give me that. It was more, Small movie, big ideas.

The book had been out there for 20 years waiting for someone to see in it what you saw in it. It’s like you were on the beach with a metal detector and found a diamond ring.

Truly! And through random coincidence — had I not read that review of Interior Chinatown, I very likely would not have discovered this book.

Did you end up reading Interior Chinatown?

I didn’t! I read this book instead, fell in love with it immediately, and just ran with it.

So here’s the thing about this book, and movie, that I truly loved: It’s obviously a satire of the ways in which the machine cranks out certain kinds of art for people in a cynical way. It’s a satire of the way white audiences relate to Black art, and it’s a satire of the publishing world in general. But the essential piece of satire is about how the business side of art flattens everything. Monk writes the dumbest thing he can, and it becomes a success.

What I find so fascinating, and why I loved it so much, is that at the same time you’re getting this pretty broad, comedic, satiric look at a set of issues, you’re also getting a lovely, well-wrought, nuanced story of a man and his sister, and his brother, and his ailing mother, and all of the other people in his multidimensional life. Usually with satire, you just get the pointed humor, and after a while you’re like, Okay, I get it, you’re making your point over and over again. This movie, and book, are split down the middle. Half of it is the satire, and the other half of the movie is a story that proves the point the satire’s trying to make. I don’t think I’ve seen that before. Was that part of what made you want to do this?

Yeah! I told everybody who came aboard that I wanted to make something satirical but not farcical. When satire becomes too heavy, it can collapse under its own weight. I tried to get the balance in the script, but then sometimes when we were shooting it would drift. Where I really found the tone was in the edit. There are a couple scenes that were more broadly comedic. One of our actresses was Miriam Shor, and she’s incredible at improv. At times I’d let the camera roll on her and her scene partner, and she’d do amazing stuff that I thought, For sure, that’s gonna be in the movie. Then in post, I’d see, Oh, this is a little too silly. Other times, there were moments where it would get really dark and dramatic — like a plane in a nosedive, it was hard to pull out of that to get to something with more levity. So it was just really sanding down the edges once we got into post to figure out what felt right.

Tone is the hardest part of making anything. I used to work on The Office, and one time we were visited by the British Office people, Stephen Merchant and Ricky Gervais. They told us something I think about all the time: If they had a scene that wasn’t working, they’d do three takes in a row. The first take, they’d do it as boringly as they could. Like, this is a drama or a documentary involving boring people in a boring place. Then, they would do the craziest, broadest, silliest, most over-the-top take possible. And then they’d aim for the middle of those two. What they said, unsurprisingly, was that most of the time, that’s how they got to the right tone, since that show was alternately absurdist and very real. But sometimes they’d watch the super-boring take and say, “We like this! We’re gonna use this one!” So you never know. Tone is the only thing you have to search for in every moment. Every script, page, line of dialogue: “Is this right? Is this right?”

As we did friends-and-family screenings of the film, we would frequently ask people, “Is this a comedy or a drama to you?” Some people would say “a dark comedy,” some would say “a drama with a lot of levity,” others would say “dramedy.” Now that the movie’s out, it’s interesting to see that it’s being discussed as a comedy in many ways. I didn’t see that coming.

That’s probably good, right? You would rather have people go into it thinking it’s a comedy and being surprised by the nuance and the seriousness than the other way around.

Absolutely. I wanted this to be a movie where people laughed and had a good time, because especially when you’re dealing with issues of race, the impulse for everybody is to be super self-serious — which is one thing that the movie’s trying to talk about. I never wanted people to feel like they were being lectured for two hours about race in America.

You’d never written a movie or directed anything before American Fiction. Then you option the book and write the screenplay and sell the movie and make the movie and it stars Jeffrey Wright and Tracee Ellis Ross and Issa Rae. You edit the movie, it comes out and wins a bunch of awards and festivals, and now people are talking like you’re gonna win an Oscar. First of all, how dare you! But I want to talk about the moment when you were trying to get people to buy the movie, because I can’t imagine it was an easy sell. What was essentially your pitch?

The script. This was both very, very easy to get made and very, very difficult to get made. I went and talked to Percival, who’s an amazing guy. I’ve never met somebody who gives less of a shit about anything. He doesn’t care about awards, doesn’t care about money, all he cares about is making art. His publisher had to tell him to stop writing so fast because “if you release a book a year, you’re cannibalizing the sales of your previous book!” I went over to his house for dinner and he brought out an abstract painting and goes, “This is an abstract painting I did for you! It’s about Charles Mingus.” And I was like, “Okay, man! Thanks! Cool!”

Can you describe the painting?

It’s completely abstract. I’m still trying to understand where Mingus is in it, but I appreciate it! While I was there, he was telling me a story and said, “Yeah, I was breaking this horse …” I go, “What?” And he goes, “Yeah, I have a ranch in town and we break wild horses.” I was like, “What? Where do you find time to do this?” He’s also a professor at USC of creative writing. He’s an amazing man.

After talking with him, he gave me the rights for free for six months. He said, “You sound passionate about it, so go write a script and if anything comes of it, you can pay me after that.” I went and wrote it on spec, and then I sent it out to like 14 producers and a bunch of them were interested. I ended up going with T-Street, Rian Johnson and Ram Bergman’s company, because they green-lit it in the room. Then we sent the script to Jeffrey and he signed on after a few months. At that point, we had T-Street, we had financing, Jeffrey, the script, and I’m attached to direct. We were preparing to take it out to distributors, and I’ll never forget, my manager called and goes, “Get ready for a bidding war. There’s gonna be so much money. We’re gonna sell this for so much money. It’s gonna be crazy.”

What a stupid thing to say!

I know! I was like, “Oh, shit! Okay! Great! Wow! What? Okay! Sure!”

It’s like a stand-up comedian saying, “I’m gonna come onstage in a couple of minutes and you’re going to see the funniest shit you’ve ever seen. I’m gonna destroy. Let’s go!”

And then you hard cut, and guess what?

The thing is, I believed him! We were meeting with so many people — every streamer, every big studio. And in every meeting it was, “Oh my God, we love this script. Oh my God, we love Jeffrey Wright. Oh my God, what’s your vision?” I started to think, Okay, maybe we are in a bidding-war situation! Then there was nothing. Silence. We ended up getting one offer from Orion/MGM, who we went with, and then a second company offered us millions of dollars less than the production budget. The response I heard from so many people was, “I wish I worked at a place where we could make this movie.” I knew the industry was risk averse, that’s not surprising, but I was truly taken aback at how risk averse. The people saying, “We can’t make this movie” are the people who make multiple $150 million movies a year.

Isn’t that one of the weirdest things about the world we’re in now, that a $150 million movie is less risky than a $3 million one? I assume it’s a combination of IP, algorithmic programming, built-in audience, global appeal, how’s it gonna open in China, blah, blah, blah. But there’s something fundamentally so stupid, even for Hollywood, about the idea that it’s less risky to make The Marvels than it is to make your movie for some small number of millions.

Totally. Under $10 million. Significantly under $10 million. If they made this movie and it was a flop, nobody’s losing a job, nobody’s going bankrupt.

It’s money they bury in the surplus charges of other productions.

The budget for my movie is probably what was spent on COVID protocols for The Marvels.

It’s the ham-and-cheese-sandwich budget on The Marvels. I was thinking about this the other day after someone brought up Steve Buscemi. To me, Buscemi invented the “one for me, one for them” thing. He would lend his talents to Con Air or Armageddon, and then he’d be in a tiny indie movie that was clearly the thing he wanted to do.

Trees Lounge.

He would oscillate, and you’d be excited when you saw some big dumb movie and Steve Buscemi would show up, and then you’d go see the real movie that he wanted to do. I wonder why studios don’t function that way. If you make Avatar 7 and it earns $5 billion, why not say, “Hey, we’re going to take $30 million of that profit and make three $10 million movies?”

My theory is that it’s tech, and the way it has its tentacles in everything. You read about WeWork and the guy was like, “We need a WeWork Costa Rica!” and everybody’s like, “Why? No, we don’t! Everybody just wants to surf in Costa Rica!” But he’s like, “We need a presence there!” There’s this perpetual growth mind-set in tech that’s, “We need more users every single quarter until we plateau because every person in the world is using it.” Do you feel like that’s what happened? I feel like it’s the influence of tech on everything.

The influence of tech in Hollywood is a uniquely shitty merging of ideals. Hollywood famously is “nobody knows anything” — where do ideas come from? How do people interpret art? How do we reflect the culture back on itself? And then tech tries to sacrifice everything for the sake of efficiency. When you merge those things, you get a Hollywood that doesn’t allow for any weird tendrils of creativity. How many great shows and movies came from one person standing up and saying, “I love this. We’re gonna do this. Is it gonna work? I don’t know, but we’re gonna try because I believe in it.” The tech approach is to eliminate that line of thinking. This is the living nightmare we’re in right now.

I worked at SNL back in the late 1930s, and whenever I was particularly happy with something that went on air, this one writer there would say, “We’re selling lightbulbs, man. Just remember.” This is when GE owned NBC. And he’s right that we should all understand we are making a certain bargain, which is you gotta make people money, and if you don’t make people money, they don’t make your stuff. That’s fine. What I can’t really abide is the idea that now the tech bros have come in, and now it’s, “How do we make a perfectly smooth pebble that is inoffensive so that everyone in the world will subscribe to our service?” That’s a bad version of Hollywood, and I fear it’s the one we are headed toward.

To your point exactly, this movie exists because three people were willing to risk something to make it. It was like, two people at T-Street and then one person at Orion. Without those three people, this movie doesn’t get made.

What’s sad is that you’d hope the folks who have the other attitude would have shame. That if they pass on something and then it comes out and it’s an incredible piece of art and a financial success, they’d feel shame about having done so. But they don’t. They couldn’t care less, because they weren’t approaching it from the standpoint of “Can we make something good that makes money?”

Do you remember that STX article in The New Yorker years ago?

I can’t remember.

It’s that company that had a bunch of funding from Chinese billionaires, and they were asking the new head of the company if he would make movies from the past. One of the ones they asked him about was, “Would you make The Shawshank Redemption?” Like, a universally beloved movie. And he said, “No.” And I’m like, You know that that’s a successful movie.

As we near the end of our talk, I want to discuss the ending of your movie without spoiling the ending of your movie.

Is that possible?

Well, I want to talk about the concept of endings. I know you shot multiple endings, and we’re not going to talk about which one you chose. But when you were considering all of them and their different tones, what was most important to you? That it felt true to the story? That it left the audience with the right idea of what was going to happen to these characters?

I wanted it to feel emotionally and intellectually satisfying—and so I actually went with an ending I was reluctant to use. After we did a test screening with a different ending, there were a lot of people who said, “Don’t touch the end, I loved it.” But there was also a significant portion of the audience who said, “I like the ending on an intellectual level, but not on an emotional level.” And me wanting to be a stupid auteur, I thought, Well, I don’t care about the emotional! Let’s just keep it intellectually satisfying!

But at a certain point, you realize that the people who are around you are there because you trust them, and I started trusting the people who were saying, “Try to satisfy both audiences.” Now I’m so content with the ending that we chose. There’s something to our job about sticking the landing: You can have something that’s really flawed, but as long as you stick the landing, it makes up for so much of what you just watched.

One person I talk to a lot about endings is Damon, because he’s so haunted by what happened with Lost. I’m not speaking out of school. He’s talked about it in a bunch of articles, that the ending of Lost and the response to the ending of Lost was very upsetting for him. I learned from him that you want to make something feel of a piece with what everybody’s just watched. Even if it isn’t “intellectually satisfying,” even if it’s not “clever,” if it’s emotionally satisfying and feels like it’s tied the thing up in a bow, people are going to forgive a lot of earlier mistakes.

It’s probably true that the moment you actually begin to mature as a writer is when you stop caring about something being intellectually satisfying and you start caring about it being emotionally satisfying. It’s like, do you care about what the cool kids are gonna say about your movie, or do you care if the movie actually affects people in a real way? I spent so much of my youth concerned about what certain people would think of what I did instead of, Is what I’m doing good and interesting and meaningful? It was Greg Daniels who basically taught me that — it’s the line from Fight Club. “How’s that working for ya, being clever?”

It’s funny you say that. One of the producers on the film was Ben LeClair, and he was the one who was saying, “Don’t do the cool thing.” He kept telling me that: “I know this is cooler, but we shouldn’t do that. It’s a bad idea. We’ve made something that feels more big-tent than that. You can invite more people in.”

Something I was really worried about is that we were making a movie with a bunch of Black people in it, and that it would scare away people who weren’t Black. Movies and TV shows with predominantly Black casts don’t necessarily feel like they’re accessible for people who aren’t Black; that’s just the reality of the industry and the reality of what people see when they see a movie poster with a bunch of Black people on it. So it’s been gratifying that as we’ve shown the movie to Black audiences, white audiences, mixes, older people, younger people, all across the spectrum, there is a big swath of diversity when it comes to people who’ve enjoyed it. One of the reasons why is because I followed Ben’s advice and didn’t make something that would be cool for people in New York and L.A. and alienate everyone else. I wanted to call the movie Fuck! When I sent you the script to read, it was called Fuck!

It was, and there’s a textual reason for that.

It makes sense why I wanted to call it that, but everybody was super-anti, and I was like, “No, fuck it! It’s supposed to be radical, man! Get in people’s faces!” That was my hill to die on because that was cool and making a statement. And then everybody was like, “Yeah, but what if this means the MPAA won’t give it a rating and then it won’t be shown anywhere except for your hipster theaters in NYC and L.A. Is that cool?” And I realized, “No, that’s not why I made this.” So we changed the title, and I’m really happy they convinced me to do it.

Briefly, one last story. When I was on The Office and Jim was going to propose to Pam — spoiler alert — they shot three versions of it. Version one was the cameras were completely surprised, like the documentary crew had rushed to catch up and were across the street shooting; in version two, it was like spying from across the street; and then in version three, they were up next to them shooting it like a normal TV show. In one of the versions from across the street, the idea was that you couldn’t hear anything they said. It was a silent film. You heard traffic whizzing by and birds chirping and stuff, and you saw Jim get down on one knee and open a box and Pam gestures in response.

So we shot all those versions, and they showed the version that was silent, and the hair on my arms stood up and I felt like I was witnessing something so beautiful and great. It had echoes of the British show, the famous scene where Tim takes off his mic and talks to Dawn, and then he comes out and goes, “She said no,” or whatever. I was like, “This is so lovely and ethereal and amazing, and such great filmmaking,” and then we had this huge debate.

Eventually, Greg Daniels and Paul Feig and others who shot it were like, “We’re gonna do the version where you can hear them talk.” And I was like, “Why?” And they said, “Because you have five years of an audience who’s deeply invested in a romance. You want to deny them one character saying, ‘I love you, will you marry me?’ and the other saying, ‘Yes, I love you too!’? Why would you deny them that? It’s already a documentary! We have all these kinds of layers and membranes between the audience and the people. Don’t do the super-arch thing all the time, do it in the margins.” Sometimes when a beloved character is proposing to another beloved character, maybe just let the audience be with them and have a nice emotional reaction.

Anyway — I said I had a thesis, remember?

Okay, yeah.

My thesis was: Given the writer you are and the ways you worked in journalism and TV and now movies, given the subject matter, given the fact that the main character in the book is himself a writer, given the fact that you’re drawn in life to projects with multiple layers, stories that aren’t one thing or another but rather are many things, many nuanced things layered together — I think that this story is the story that you were born to tell as your first project. Do you think I’m right?

Yeah, absolutely.

I nailed it!

It’s crazy that you say that, truly. I was talking to my girlfriend earlier today and called the movie my life’s work. It was a joke, but I was kind of not joking. Literally everything I’ve done before this … I was raised in a weird household with a Black Republican father and a white liberal mother, and even from the earliest days, there was nothing taken for granted and everything was more complicated. I saw the differences in both sides, and people’s different opinions about things, and so I sort of really grew up feeling like everything is more nuanced and complex than we really allow for, particularly in American culture. So yeah, this is absolutely the culmination of everything that I’ve done in my life. It feels very weird.

Do I win something?

Yeah, you got to do this interview!