This article was originally published on February 25, 2021. We’re recirculating it now that Lost is streaming on Netflix.

When the Lost finale aired on May 23, 2010, it was a very big deal. It was also, quite possibly, the last big deal of its kind.

Born from an idea generated by then–ABC chairman Lloyd Braun, crafted into pilot form by co-creators J.J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof, then fleshed out over six seasons into a character-driven, mythologically rich, Emmy-winning existential adventure, the island-based drama had become one of the biggest pop-cultural obsessions in the world by the end of the aughts. Just one testament to what a big deal it was: When the White House signaled that the president might deliver his State of the Union on the same night that the premiere of the sixth and final season was scheduled to air, Lost fans went so ballistic online that Barack Obama’s team made sure to convey they would get out of Lost’s way.

Because Lindelof and co-showrunner Carlton Cuse, along with ABC, announced their plans to end the series in the middle of the third season, and because the show’s mysteries were avidly dissected online like none had been before, the fixation on the final episode was extreme. ABC’s promos for “The End,” Lost’s last chapter, hyped it as “the most anticipated episode in television history.” That only sounded like a slight exaggeration.

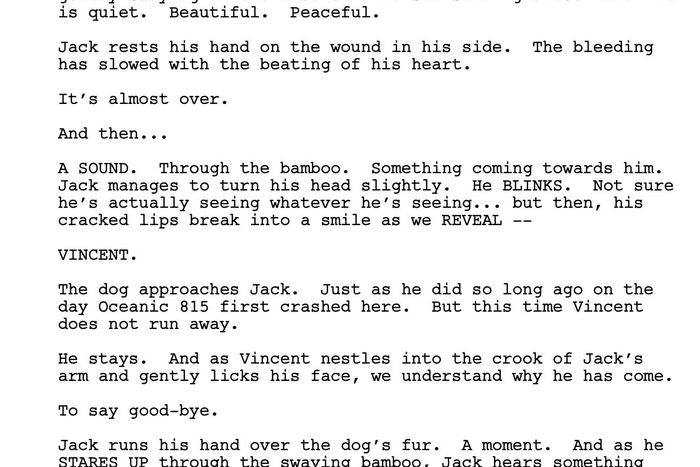

The two-and-a-half-hour finale, which cost upwards of $15 million to make, wrapped up six seasons of relationship and time-jumping narrative development by having Jack Shephard (Matthew Fox) battle John Locke (Terry O’Quinn) — who at that point had become the human embodiment of the show’s famous Smoke Monster — in an attempt to save the island where the characters crash-landed, while revealing that its parallel, non-island timeline, dubbed the flash-sideways, was really a bardo where all the key figures from the show met to help usher Jack into the next realm. The show would culminate in the flash-sideways with Jack & Co. gathering in a church and, on the island, Jack dying in the jungle, while Vincent, the Labrador that belonged to young Walt (Malcolm David Kelley), lay down beside him.

When the finale aired, it sparked divided responses (understatement) from fans. Some loved the emotional way in which Jack’s journey and that of his fellow survivors of Oceanic Flight 815 came to a close. Others were extremely vocally angry about not getting more direct answers to the show’s many questions. Still others came away from it all convinced that the castaways had been dead the whole time. (They were not dead. They really weren’t.)

What was semi-clear at the time and is even clearer now is that the broadcast of the Lost finale would mark the end of something else: the truly communal broadcast television experience. Subsequent finales would be major events (see HBO’s Game of Thrones) and even draw larger audiences (2019’s final Big Bang Theory attracted 18 million viewers, compared to the 13.5 million who tuned in for the Lost farewell). But nothing else since has felt so massively anticipated and so widely consumed in real time the way that the end of Lost, the Smoke Monster Super Bowl, did in 2010.

Vulture did extensive interviews with writers, cast, and crew members, who reflected on the development of “The End,” the making of the still hotly debated episode, and the cultural conversation it continues to generate. Because, yes, of course, we had to go back.

The Beginnings of ‘The End’

Despite accusations from critics that Lindelof, Cuse, and the rest of the writers were just “making up” Lost as they went along, the seeds for certain elements and imagery that would appear in the finale started to be planted as early as season one. In an unprecedented move at the time, Lindelof and Cuse later laid the groundwork for the show’s conclusion by determining when it would end in the middle of the third season.

Carlton Cuse, co-showrunner, executive producer, and co-writer of “The End”: We went to ABC in season three and said, “We want to end the show.” I believe the first counteroffer was nine seasons. We were like, No, we can’t. But we needed to know [when we would end]. It was impossible to move forward without a clear sense of what the rest of the journey was. The best we could do was get six seasons. At least we were able to end the show on our own timetable. That was something that hadn’t been done before.

Liz Sarnoff, writer and executive producer: The first three seasons, we did so many episodes. I mean, we did like 22 to 25 a season. There wasn’t a lot of time to speculate on the future. It was more like, What are we shooting next week? But there were certain images I know that Damon always had [in mind for the last episode] in the beginning. Certainly one of them was Jack’s eye closing.

Damon Lindelof, co-creator, co-showrunner, executive producer; co-writer of “The End”: I just want to make this very clear and I want to make sure that it’s also in print: We’re in memoir territory. I’m giving you what my honest recollections are, but because we’re talking about memory, they are not to be trusted.

I believe as early as midway through the first season, when I was openly saying “This show needs to end” — as part of my, you know, screed — it was “Show opens with Jack’s eye opening, ends with Jack’s eye closing.” Once he’s dead, show is over. If it wasn’t season one, it was in the break between seasons one and season two. It was early.

Eddy Kitsis, writer and executive producer: I feel like we also had the Vincent component. [In the final sequence, Vincent, the dog that belonged to Walt, lies down next to Jack as he’s dying.] I remember thinking about that for years.

Lindelof: There were certain things that we were already guided by and locked in on. The first conversations about the character who ended up being the Man in Black were all synonymous with “What is the monster?” Those conversations were happening as early as that mini-camp [for the writers after season one].

The idea that the island was a cork, like literally stopping up hell — we were all Buffy fans, particularly in the season when Goddard and Fury were hanging around quite a bit. We did refer to the island as being a cork in the hellmouth. By the time Jacob explains that to Richard Alpert in the final season, that was an idea that was there for a very long time.

Josh Holloway, James “Sawyer” Ford: I remember one time in season one, I told Damon and Carlton, “You know what, the island moves. It’s like the Death Star.” And Damon got all weird with me and he was like, “Who’ve you been talking to?” I was like, “I haven’t talked to nobody. Pretend I never said anything.” And I walked away. So I quit my theorizing right there.

Lindelof: The idea that the island was moving was one of the crazy ideas that J.J. threw out while we were shooting the pilot. Certainly once we had the [writers] room together in season one, I remember having those conversations, because Carlton was pitching it in terms of, like, constellations or something like that. We all always loved the idea and wanted to keep it as a secret. When Josh mentioned it, I’m like, “Oh, okay. Someone is basically talking to him.”

Jimmy Kimmel, Lost super-fan and host of Jimmy Kimmel Live! Aloha to Lost, the post-finale special: Those motherfuckers, J.J. and Damon and Carlton, tried to do a terrible thing to me about, I don’t know, maybe somewhere in the second season. I was like, How does this end, what’s going on? I was constantly pestering them to know what was happening. They said, “Here’s what we’ll do. We will tell you how the series ends. We will write it down, and we’ll put it in an envelope. And then you can decide whether you want to open it or not.” I said, “I am not going to fall for your psychological torture,” because I know I’d wind up getting high and opening that thing at like two o’clock in the morning and then inside would be a note saying, Aha, we knew you couldn’t wait or something. To this day, they swear they were going to write the ending down, put it in the envelope, and leave it to me to decide whether I wanted to open it or not.

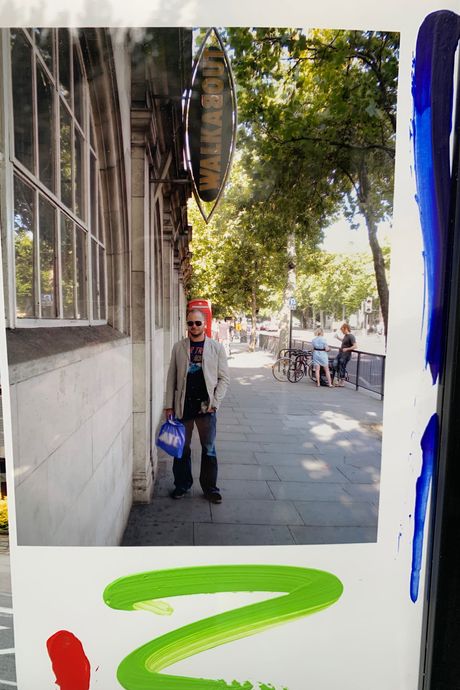

Jack Bender, director of “The End”: This was going into our finale season, and we were in London doing press. Damon and I went to the Tate Modern, and we decided to walk back [to our hotel]. He said, “Let me tell you the story of how we’re going to end the show.” So he proceeds to tell me the architecture of what’s going to be happening along the way, and he says, “Okay, now let me tell you about Locke.” We’ve gotten over the bridge, and we’re now walking along somewhere in London, heading back to the hotel. As he proceeds to tell me about Locke, I look up above me and I said, “Damon, stop.” And he said, “Why?” And I said, “Look up.” And we were in front of a pub called the Walkabout. I look at Damon and he looks at me and he goes, “Oh my God.” [The season-one episode that reveals Locke was in a wheelchair before landing on the island is called “Walkabout.”] I said, “I have to take a picture of you in front of it.” So I do that. Then he says, “Let me take one of you.” He takes the picture of me and in the picture, as he takes the picture, a man in a wheelchair wheels right by.

Lindelof: Yes, that is true.

Into the Writers Room

Over a two-week period in the spring of 2010, the Lost writing staff gathered, as a group and in individual writing sessions, to craft the final episode.

Cuse: When you make a show that goes on for six years, there’s sort of two parallel journeys that are occurring. There’s the one that’s happening onscreen, and then there’s the one happening offscreen as all the people who make the show get deeply bonded and connected to each other. It was even more intense with Lost because everybody realized that it was such a significant thing and would probably be a huge demarcation point in all of our careers.

Sarnoff: Our feelings about the finale were always, always, that it was going to have to be very emotional and character-based because we found when we gave answers to mysteries and stuff like that, the audience would normally reject them. Mystery shows like that are so tricky because nobody wants the mystery to end, but they want answers.

The level of difficulty was, I think, the hardest I’ll ever encounter.

Cuse: I remember very clearly just trying to stick to the same process that had gotten us to the 120th and 121st episode. I think it was really important that we tried to keep our focus on that process, which was, Let’s make a show that delights us. Let’s not try to anticipate this reaction or that reaction. Let’s make the finale that we ourselves want to see.

Lindelof: I spent a disproportionate amount of time trying to figure out if there was a way to get Walt into the finale, other than being in the church. And would it be weird for him to be in the church because he’s grown now? He looks so different than he did in the pilot, and everybody else in the church kind of looks like they did in season one.

Sarnoff: Damon would always say, “There’s questions that make you go, Ohhhh. And then there’s questions that make you go, Huh. You don’t want the Huh.” Particularly in the final scene of the finale, you don’t want people going, Who’s that kid?

Cuse: Malcolm [David Kelley] grew up so we had to figure out how to make that work in the context of our story. It was a conundrum trying to figure out how we could bring that character back, but it felt like a missing piece to not do that given what happened to him.

Lindelof: There was a lot of Walt worry and that led to us making this epilogue for the DVD called “The New Man in Charge,” in which we resolve the Walt of it all.

People don’t consider it part of the canon. I do, but the look on people’s faces when they’re like, “What about Walt?” and I’m like, “Oh, we did this thing, and it’s on the DVD” — they just look like they want to strangle me, so I get that.

Cuse: There was no way to answer all the open questions that existed across the prior 119 episodes of the show. In fact, an attempt to do that would just be didactic. We sort of tried a version of that with the episode that was a couple before the end, “Across the Sea,” which was this very mythological episode about the origins of Jacob and the Man in Black. That was sort of what answers look like. And I don’t think it was great.

Lindelof: I spend a lot of time really anxious about whether or not something was good or whether or not people were going to like it. But I don’t think that I was really thinking about what other people were going to think about the finale. I was thinking about what I felt about it, and I was like, “Oh, this is what I want to do.” We had been talking about this for a really long time, so it was pretty good vibes.

Sarnoff: It was one of the more emotional times I can ever remember in any writers’ room. I also got cancer in season four of the show, and it was an experience that brought us all very close. And that was the year of the writers’ strike and all this other stuff. So it had been an intense time in the last couple of seasons, and it was hard not to be aware of how much the show meant to us but also how much it meant to other people. Because the Lost fans were like no other fans I’ve ever experienced, and they were pissed the show was ending, but at the same time, they were so emotional about it.

Kitsis: At about nine o’clock one night, Damon’s AIM came on — it always had this weird punch sound — and he’s like, Are you up? I was like, Of course. He was like, I’m sending you and Adam [Horowitz] the final piece. And he sent us that Christian scene [with Jack in the church], the first draft, like literally right after he wrote it, just to see what we thought. There was this feeling of specialness because it’s like, we were all in on this secret together.

Adam Horowitz, writer and executive producer: I remember feeling, Wow, this is it. And it was beautiful.

Keeping the Secrets of Lost

Throughout the show’s run, the Lost team took steps to make sure spoilers didn’t leak. (Note: That did not always work!) But the details surrounding the finale were in such demand that they were guarded with extra intensity.

Holloway: We were all so anxious to get the last script because we were like, How are they going to get out of it? You know, we didn’t see how they were going to end the show. I was like, “Hey, I got a cabin up in the mountains of Colorado if you need to hide from people trying to kill you if you don’t do the ending right.” You know, we were joking with Damon and Carlton. They’re like, “Okay, we might take you up on that.”

Michael Emerson (Benjamin Linus): That last script was a high-security script. When you got pages, which were usually the day you worked, they were printed on red paper, which is unreproducible. This was especially high stakes. This could not get out into the world.

Maggie Grace (Shannon Rutherford): They really enjoyed the spy games of getting people scripts. It was early then, before Marvel took it to another level of paranoia.

Jorge Garcia (Hugo “Hurley” Reyes): The scripts got more and more secretive as the series progressed. I had to even purchase a special mailbox that had a lock on it so that they would be able to leave the scripts for me. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be able to deliver a script unless I was home. We just kinda strapped it to a bench in front of my house. If someone really wanted, they could easily just steal the whole mailbox.

Yunjin Kim (Sun): I got the script, but it was thinner than I expected. A lot of the scenes that I was not involved in were missing. But it was like that the last five or six episodes. In season six, we had a lot of pages missing. The whole exchange between Jack and his father, Christian Shepherd, I definitely did not get those pages.

Emerson: My whole gig at Lost was kind of operating in the dark. I got comfortable with that. So the finale, because we didn’t get a complete script, it was a lot of guessing — a lot of wondering how things got put together, what they would mean, what they would look like.

Henry Ian Cusick (Desmond): I had phoned Damon and Carlton before about certain things, but never to say, “What is going on?” And here I said, “I need to know what’s going on with my character.” They said, “We don’t want to tell you the ending. Are you trying to get the ending out of us?” I was like, “No, I just need to do my job. I don’t really know what’s going on.”

I couldn’t understand what I was doing [in the flash-sideways]. Why did I want to get everyone back to the church? Why was I reawakening everyone, what was my objective? At the end I got there. I knew what was happening as we were filming it.

Cuse: We were really concerned about anybody figuring out what was going to be happening in the big church scene. So [during production] we hired two extras that looked like Sun and Jin and we put them in wedding clothes and we put them outside the church. And we were taking them in and out in a way that any paparazzi or people that were trying to figure out what’s going on would think that we were staging Sun and Jin’s wedding.

Kim: What? No, no, no. There was no double me in a wedding dress. No way.

Garcia: I believe they had a woman who was like a Sun double dress up in a wedding dress and they would shuttle her periodically [to set]. I never met her. I remember seeing a woman in her wedding dress and them often referring to that scene as Sun’s wedding, even though we knew that wasn’t anything that was going to go on in it.

Kim: Wow. I had no idea that was happening. They didn’t tell us anything we didn’t need to know.

Filming ‘The End’

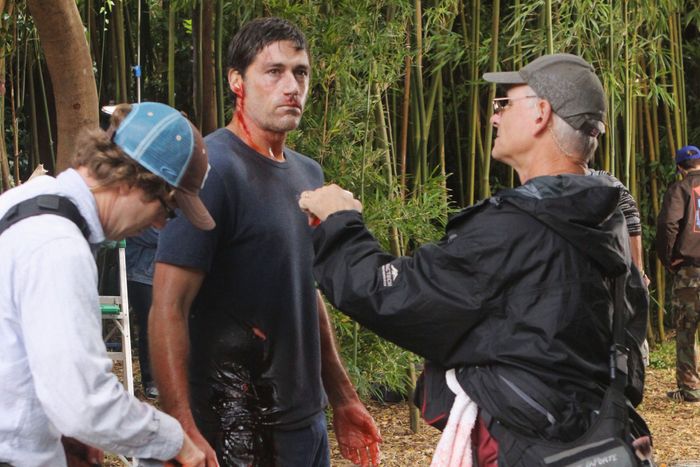

Production of the Lost finale, which took place in March and April 2010, was an emotional experience for members of the cast and crew, who knew it would be their last time shooting in Hawaii. The work could be physically taxing, daunting, and occasionally a little scary. (There was a bit of a mix-up involving a knife.)

Holloway: I remember the [first] day we came to work, we were working on the beach, all the chairs around, and we all looked at each other, smiling. “Well, they did it, they frickin’ did it. It’s pretty good. What do you think?” Some loved it. Some didn’t love it, but we all thought it was a good script and we were excited to do it.

Cusick: I think people were happy that it was ending. I was one of the few that was like, We could do another season. There’s a lot more story to be told here.

Terry O’Quinn (John Locke): It was physically stressful because you know, I’m not a kid. I think at that time I was 58. I remember Matthew [Fox] running down the hill and diving at me and I thought, This is going to leave a mark.

Holloway: Didn’t me and Evy [Evangeline Lily] jump off a cliff?

[Note: Yes. Yes, they did.]

Holloway: I remember how crazy our stunt guy was. I loved him. He was my stunt guy all those years and the stunt coordinator at that point: Mike Trisler, ex-fricking Special Forces guy. So he’s like, “Okay, let’s do this. I’m going to die.” I’m like, “Don’t die, bro. It’s like 70 feet high. Just jump, you know?” He’s like, “No, it’s cool. It’s cool if I die.” You’re fucking crazy! And he went ahead, 70 feet off that cliff. They have plaques on that cliff of the people who have died. So it’s pretty major. I remember being on top of that thing and doing the fake run-up, like you’re going to do it. You’ve got to get pretty close to the edge. Oh, shit. That was scary.

Bender: We were really up there [on that cliff]. The actors were really up there. On any set of mine, it’s always safety first. It just is. I think our line producer was really reluctant to have a shoot up there and for all the right reasons. Because it was coming off of the ocean and the waves were breaking, the spray was up there at times, which made it visually fabulous, but also all the more dangerous. So we mapped out the action, totally safe and broke down all the shots.

But there was one moment in that sequence which I will never forget as an executive producer, as a director, and as a human being.

O’Quinn: There was a big fight [between Locke and Jack] with knives and all that kind of stuff.

Bender: We had a fake knife and a real knife. The real knife, like whenever you’re doing a movie, is dulled down. But it is a real blade so it won’t wobble, because all rubber blades do that a little bit. Terry was working with a real knife and the fake knife. We had shot a number of shots in the sequence and were probably getting toward the end of the shoot. Terry was well rehearsed in when he would have the real knife in his hand, even though it was dull, and when he would drop it and right next to him, an inch away was the fake knife.

O’Quinn: We were wrestling and wrestling and the fire hoses were going and there was water and at one point, I had the real knife out. [Matthew] saw me pull it out and then we wrestled with it.

Bender: We were doing this switch with the blade and Terry picked up the wrong one.

O’Quinn: I plunged it into Matthew’s side. Well, Matthew had a pad [under his shirt] that was probably about the size of your extended palm, where I’m supposed to stab him. It was just to protect him from where I was supposed to stab him. I don’t think I held my hand out to wait for the exchange because we were caught up in the action. So I stabbed him with a real knife.

Bender: The scene ended with Matt rolling off and next thing I know these guys are fucking laughing. I’m going, what’s going on? Terry goes, “I fucked up.” I went, “Oh my God.”

O’Quinn: Fortunately, I stabbed him where I was supposed to, so it didn’t pierce his pad. I don’t think any harm was done. I realized when I tried to stab him and [the blade didn’t retract], I said, “Oh, this is not the right one.” But generally speaking, when you use a knife in a fight like that, the real knife, you would have difficulty cutting butter with it. They won’t give you a dangerous knife to wrestle with.

Emerson: I chiefly remember being injured [during production of the finale]. I had torn the meniscus in my left knee on-set. We were shooting a scene, it must have been maybe three or four episodes before the finale. I was just sitting, waiting for the next camera shot, and somebody said, “Okay, camera’s up, let’s get going.” And I was sitting cross-legged, and I just, like a young man would, heaved myself up out of that position, but it was more than my knee could take and I heard something snap.

There’s a scene [in the finale] where Hurley and I meet at a rocky stream, and I thought “Oh my God, how am I going to manage walking on these slippery rocks with a bad leg and what happens if I go down” and all of that. That was a bit of a preoccupation with me, so I may not have been as spiritually present as I would have wished.

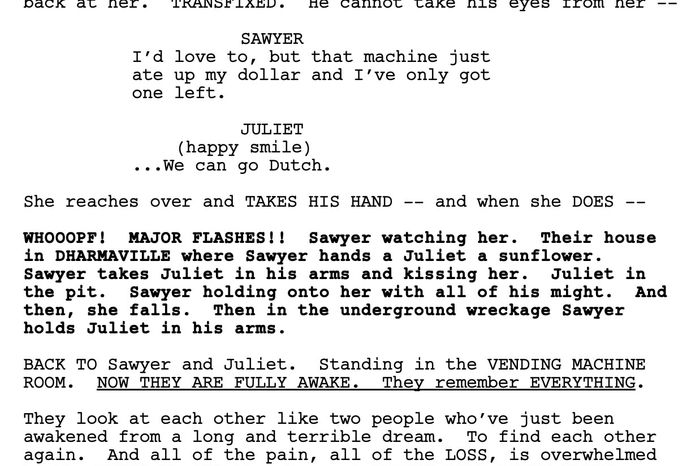

While previous seasons of Lost included regular flashbacks and, later, flash-forwards, the sixth season featured what were called flash-sideways: glimpses of the characters in a parallel universe where Oceanic 815 had never crashed. In “The End,” the flash-sideways realm was revealed to be, in Lindelof’s words, a bardo where several characters’ memories of their lives on the island were triggered by touch or moments that echoed things that happened post-crash. One of the more emotional trigger moments involved Lost power couple Sawyer and Juliet realizing that they had known each other in another life on the island.

Lindelof: From a writerly standpoint, it’s impossible for me to convey to you in words what the rules of the sideways were, other than to say we called it a bardo in the writers’ room, which was largely based on a construct in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which is this idea that when you die, you experience an afterlife where you do not know that you are dead, and the entire purpose of that afterlife is for you to come to the awareness that you have died.

I was able to give the show so much rope in the sideways because it was literally the place that they made together so that they could find each other. Contrivance and Dickensian coincidence, which is the stuff that we loved so much in the show, was really able to allow its freak flag to fly in that material.

Holloway: I remember going, “Man, is this going to be cheesy?” Like, I’m getting a Coca-Cola and I touch her hand and I have to do this thing where I have this flash of memory. We were all thinking, Oh man, I wonder if it’s going to work. And when they did it, it was awesome, I thought.

Lindelof: We made sure that people understood that in the ever-after Sawyer and Juliet were going to be together. Those things were musts, they needed to be serviced. And hopefully the good side of fan service, where the fans really want you to listen to them.

Elizabeth Mitchell (Juliet Burke): I remember [while shooting that scene] the air conditioning was rattling like crazy and it was driving sound crazy and then we were all talking about it. Then I just looked at Josh and the characters were just there and it was — I just remember thinking, Oh yeah, here we are.

Holloway: Elizabeth was so sweet, is so sweet, as a person. Like, you can’t shake her. I tried to get her mad. I’d just be an asshole sometimes, like being Sawyer-ish on set. She would just be like, “Oh, Josh.”

Mitchell: Jack was filming that scene and I ended up so grateful he understood that we needed it to just go until [the right emotion] was there and I think that’s what we did.

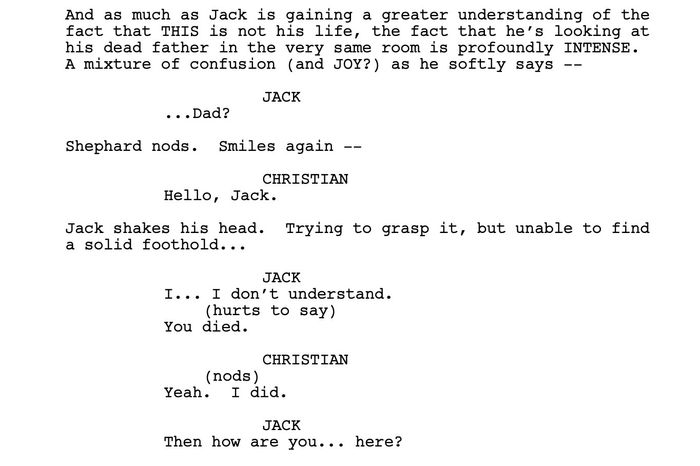

The most emotional scene in the episode comes toward the end, when Jack arrives at the church and is told by his father that he’s dead. He then enters the sanctuary of the church and finds everyone he knew on the island, exactly as he remembers last seeing them. This reunion intercuts between shots of Jack, having saved the island, stumbling to his final resting place in the jungle.

Barry Jossen, former head of ABC Studios: I woke up the next morning [after reading the script] and there were a few thoughts about what they had that really concerned me so much that I couldn’t let it go.

So I called them [in Hawaii]. I think first I called Carlton. It was a good dialogue, it was a good back and forth. Carlton is an intellectual processor, so he kind of worked his way through, he asked questions. “Let me talk to Damon,” he said. Thirty minutes later, Damon called me back.

We had our back and forth, and my recollection is whatever was bugging me was the final moment in the conversation between Jack and his father. Probably what I was looking for in that moment was maybe more answers and maybe more clarity. I think that was what might have been playing out. I do remember what Damon said to me: “I’m going to start crying. You’re really upsetting me.” “What do you mean?” “Because I’m trying to figure out what you need or what you’re wanting or what you’re saying, and I think it makes sense. I’m just so” — I don’t remember what his exact expression was — “I am just so ready for it to move forward.”

They’re literally at their hotels getting ready to go to this set and shoot the final moments of the show. And I’m on the phone saying some version of, “Yeah, but.”

Lindelof: Barry’s recollection seems to be consistent with my own. The one thing I cannot remember is what dialogue was added, if any, to satisfy his note. I know that “This was the place you made together to find each other” was already there. It’s possible that the added dialogue was Jack asking for clarity on what was real and Christian saying, “It was all real, it all happened,” but as I no longer have access to the multiple drafts and their respective dates, I honestly couldn’t tell you.

I remember being very emotional and wanting it to be over.

Jossen: We had our conversation and he said, “Okay, let me think about it. I get it. I know what to do.” There’s so much brilliance in Carlton, there’s so much brilliance in Damon. They went and did their work. And I mean, I loved it.

Lindelof: There’s stuff that makes me grimace a bit. Like it’s not quite a regret, but I think that if we didn’t have that damn stained-glass window, we would’ve gotten a full letter grade higher on the finale. The literalness of the window — that’s a part that made me grit my teeth a little bit and go like, God, you know, why? We really thought that was a good idea at the time, so we have to forgive ourselves. But it’s just a bridge too far.

Bender: My idea was to keep all the actors kind of away from each other until we got in the room in the church on the set. Because it would be so great not to have them see each other until they’re there, and yet I knew that couldn’t happen given wardrobe and hair and people running into each other and you know, the fact that people are people.

Garcia: I remember there being so many cast chairs of basically everyone who’s ever been [on the show] almost, just all lined up in two rows with everybody’s name on their backs.

Lindelof: Hanging out at craft services, I really remember regretting that Harold [Perrineau] was not there in the church. And I remember why we made that decision, because for Michael to be there, it would also mean that Walt would have to be there. And then Cynthia Watros was getting an iced tea at craft services. And I was like, Libby is in the church? That’s no dig on Cynthia. We wanted Libby there because Hurley wanted Libby there. I just remember it being very weird in addition to being very emotional.

O’Quinn: That was wonderful. It was kind of like a class reunion and graduation and a family reunion, sort of all at the same time.

Bender: I got four cameras, and I told the camera operators, who are brilliant, “I just want you to capture these moments, and I want you to follow the characters around, wider shots, tighter shots, and pretend we’re doing a documentary on all of these actors coming back together again and just shoot it all.” A lot of it was just spontaneous. Then I’d say to Jorge, “Go over and pick up Matt and give him a bear hug.” And it was fabulous. It’s everybody’s fantasy of what happens when we die. That you’re with the people you’ve lived with and you love and have argued with and it’s a room full of forgiveness.

Emilie De Ravin, Claire Littleton: It was really art imitating life or life imitating art in a sense because we’d just be off wandering around at night, chatting, laughing, catching up, hanging out around the trailers, and then go into the church and kind of do the same thing. Not exactly, but it was a really special evening

Grace: I think we had a kind of odd fake baby for Emilie de Ravin’s baby. So we were goofing around with whose baby that was and taking a lot of pictures of the baby. It was a kind of creepy doll. I think we all might have had a glass of wine later that night.

Holloway: We also got drunk, I think, while we did it. A little bit, you know, because we’re all celebrating. That was the last scene that we all did together. So we were slipping over to each other’s trailer and having a glass of wine, going back in and doing some more scene. It was great.

Cusick: I brought my family — my wife and my children were there. I remember people playing the guitar and singing. Somebody was singing “Hallelujah.” I don’t know who it was. It could have been Terry.

O’Quinn: “Hallelujah” was in my repertoire right around that time. I always took the guitar to the set there because you could always go off to the side, and Naveen [Andrews, who played Sayid] always liked to play it.

De Ravin: Daniel [Dae Kim] actually posted a video recently, I think it was on his Instagram and I reposted it. It brought back so many memories. I’m sitting next to Maggie and swaying back and forth. Oh, it’s so sweet. That wasn’t just, “Oh, it’s the finale and the last scene.” The entire run of the show, that’s kind of the vibe. It was sitting in camping chairs on the beach at three in the morning with fires — because we had them for set — sitting by the “fake but real” fire, singing. Just that camaraderie of sun-burnt, mosquito-bitten friends on the beach just singing and chilling out and really trying to embrace how lucky we were to be able to film in such a beautiful place. This was our job, and we all felt very lucky.

Post-Production

Lost episodes usually came together on tight deadlines, and “The End” was no exception. Editors began to work overtime on the episode, both while production was still in progress and after it was completed, and Michael Giacchino composed and oversaw the recording of its score.

Cuse: I think we had eight days in total to edit a two-hour series finale. And then the show had to march through all of the various other bits of postproduction, which were elaborate, including sound mixing, visual effects, music. I mean everything was crazy.

Ra’uf Glasgow, producer who supervised postproduction: The last two months of the show was really seven days a week, either starting on editorial or then moving into mixing and the other aspects of postproduction.

Michael Giacchino, score composer: I would generally have three days [to compose] and orchestrate [the music] and then we’d record it on the fourth day. It was not a lot of time, and it was a two-part finale, so there was a lot to do. And they were extra-long episodes, so there was more music than normal.

Mark Goldman, editor: All the editors, as I remember, had different times where at some point we cried watching it. I was working on the scene with Jack and his dad in the sideways where Jack finds out that he’s died. We had a screening of the show and Damon and I went back to my room to review that scene. We started just talking about the theme of fathers and dying and things like that. Then I was like, “All right, well, let me do these notes for you. Give me like a half-hour.” He’s like, “Okay.” And he hops out. I turn around and I start cutting and about 30 seconds later, I suddenly burst into tears. One of the other editors was screening for network execs and at the end of it everybody, including the editor, was sitting there crying.

Giacchino: I never read any of the scripts and then coming to the finale, I certainly didn’t read that. They were also very protective of everything in general anyway. Not that I couldn’t have gotten them if I wanted to, but it just worked better.

Jossen: There were a lot of tears in the editing room that day when we all watched it for the first time together. A lot of tears. I mean, Stephen Stemel [one of the other editors] — literally two-thirds of the way in, the most significant sound in the room was either him reaching to his Kleenex box for another Kleenex or just the sound of him sniffling.

Giacchino: What I would do is start at the beginning of the episode and work my way through it. That way I was reacting to watching it and whatever I was experiencing as I watched it, that was then put into the music. I felt like that was a better experience for the audience, to feel that it’s more spontaneous. You’re literally getting my reaction, my emotion, that I had at the moment of seeing that for the first time.

Goldman: The only time [Ra’uf] left [the mix stage] was when his wife gave birth to a baby boy. That is literally true. In the middle of the finale, Ra’uf’s wife’s water burst.

Glasgow: I drove home and got home in time for him to be born. He was born at home. I slept a few hours and came a couple hours late to the mix stage, but went straight back to the mix stage the next morning.

Goldman: What’s cool is that baby supplied the crying for when Claire gives birth in the sideways.

Glasgow: It wasn’t my son. It was my daughter. She was, I want to say 2 or 3. Those are the tricks you end up doing. You go, “Oh, we need this thing and we don’t have it.” Then it’s sort of like, “Oh, come over here and cry into my iPhone.”

The Finale Coda, a.k.a. They Weren’t Dead the Whole Time

When the finale aired, some viewers came away thinking that, from the very beginning of the series, the survivors of Oceanic 815 had actually been dead. A post-credits sequence may have inadvertently contributed to that impression, but the spread of this disinformation ends now.

Cuse: I only really have one regret about the whole journey of Lost and that was at the very, very end. Barry Jossen, he called Damon and me and he said, “You know, I’m worried that we’re going to come out of this incredibly emotional ending of this show and then slam into a Proctor & Gamble commercial and that isn’t going to be good. Is there any way to soften that or ameliorate that? Is there any footage that exists that we could put at the end to just kind of ease the audience out of the show and into commercials?”

Jossen: He calls me back at some point: “I talked to Damon. We think it’s a really cool idea. It’s the wreckage of the plane and the different props and the beach and the water and it’s all beautiful. And we’ve always loved the photos and I’ve always thought like, Wow, wouldn’t it be cool to find something to do with that? So what we find is maybe what we’ll do is we’ll cut a montage of these photos and put them at the end of the episode.”

Cuse: The only thing that we had or we could find was, sometime during the first season, the winter was coming and all of the pieces of the airplane had to get moved off the beach because in Hawaii, in the winter, the North Shore of Oahu, the whole geography changes. Huge waves come in and the beaches erode away. It was an environmental hazard. So before all the pieces of the Oceanic plane were moved off the beach, a unit went out and filmed them.

So we put that footage at the end of the show and I think that the problem was that the audience was so accustomed on Lost to the idea that everything had meaning and purpose and intentionality. So they read into that footage at the end that, you know, they were dead. That was not the intention. The intention was just to create a narrative pause. But it was too portentous. It took on another meaning. And that meaning I think, distorted our intentions and helped create that misperception.

Garcia: I thought that was a nice bit to decompress at the end of it. Then I found out the next day how people started interpreting it as a thing and I was like, Oh, okay. And people still say it. People still talk about it the same way.

Lindelof: It never even occurred to us that looking at the wreckage of the plane on the beach over the end titles would be perceived as some sort of massive reveal in the way that the very French cinema, like in Caché, when the end titles are rolling, that’s when they give you the big “Oh my God” moment.

Cuse: I think we could have done some things to make it clear that that wasn’t what you were supposed to take away. But one of the big intentions of the show was intentional ambiguity and giving people the opportunity to digest and interpret Lost as they want to if they wanted to. And at some level, you know, you can’t have it both ways.

Holloway: I’m still confused. I’ll be honest with you. I think that’s one theory. We could have all been dead. Or we could have been in like this purgatory thing. I always thought that, and still do kind of really think it was more that. To me, that’s what makes more sense. Then they kind of sidestepped it with the parallel life at the end. But I don’t know, because they always said, “No, it’s not purgatory.”

Emerson: I don’t think I could have explained the ending to someone at the moment [when I watched it]. But I must have watched it again later. And then it began to fall into place for me, and I began to be able to describe what I thought it was or what it meant in a more effective way. And then I grew happier and happier with the ending over time.

Sarnoff: That [coda] didn’t help things. Also I think a lot of people had been saying that all along and they wanted to be right. You know what I mean? It’s like if you have a theory and you can make it work based on the evidence of ABC doing that and the way we told the story, I think you’re going to go for it.

Jossen: There were always Easter eggs. So now when we’re giving them the imagery in a way that they’ve never seen it before, it would make sense that the super-fans would now want to give it meaning and they thought it was intended for them to do so. This is of course perspective because we were inside the making of the show and all the super-fans were inside the experience of watching it.

Lindelof: Whether you like the finale or whether you don’t like the finale, that doesn’t really bug me too much. But that idea — they were dead the whole time — it negates the whole show, it negates the whole point of the show. I’ve come to believe over time — whether I’m right or I’m wrong, this is where I find solace — that the people who really think they were dead the whole time did not watch the final season of the show, they just watched the finale. And many of them checked out on the show around season three. I found that if someone said to me, “Were they dead the whole time?” and I asked them, “Do you know who Lapidus or Faraday are?” they could not answer those questions. Lapidus and Faraday are not characters who just pop in in season six; they were major characters who featured very prominently in what I would call the third act of the show. Again, this is not provable data. There are probably people out there who will say “I’ve watched every single episode, and I believe they were dead the whole time.” I guess I would say, “Let’s debate. You be Phyllis Schlafly and I’ll be Bella [Abzug] and let’s dance.”

Braun: When you have a show that has exploded the way Lost did and gets into the Zeitgeist the way Lost did and is beloved the way Lost was, it’s almost impossible to end a show like that and please everybody. I’m telling you, it’s an impossible task.

Bender: The thing that I loved about the finale and we were crucified for and still occasionally are is that ultimately the show Lost was not some Marvel-esque, super-sci-fi ending. What I’m most proud of, among the many things about the show, is it was ultimately about how we live our lives, who we live them with and how we die.

O’Quinn: All you heard was the negative. I heard plenty of that, but I didn’t take it personally. I often thought in the course of the making of the show, if you don’t get it, you’re just not paying attention or it’s just not your cup of tea. It was written well enough that the whole thing, if you’d simply watched and paid attention, you would understand what they were trying to say. Or at least come to some conclusions yourself.

I know that the dissatisfaction with the end of a show is common. Even I was dissatisfied with Game of Thrones. I thought that seemed like they kind of hurried out the door, they threw their clothes on and they were gone. But I wanted to write them a letter and say, “Welcome to the club.”

Cusick: The show is not about the ending. The show is the entirety of the six seasons that you had and trying to remember all the emotions that you had when you couldn’t wait to find out what was in the hatch. That was the show. It was a time when there was no binge-watching, so you had to wait until next week, which is infuriating, you know? And yet so delicious.

Kimmel: The idea that people would put so much weight on what happened at the end is missing the point. The point of that show was the fun and the mystery and trying to figure out what was going on. And maybe that’s still part of the fun, that we still haven’t exactly figured out what was going on.

It really was the most interactive show, I think, ever. Not since the Bible have so many scholars worked so hard to interpret what was written.

Holloway: I can’t wait until my daughter gets to the right age so I can watch it with her. She keeps trying to watch it with me, but my wife is such a stickler with that. Like, “No, it’s not appropriate.” So I’m going to sneak in and watch it with her.

Garcia: I ran into Damon at an airport [last] … March? I was on my way to Atlanta to go do an episode of MacGyver. It was right when we started getting word that this apocalypse was starting. I was talking to him and his wife and then he waved his son over, who is so grown now. [Damon’s] like, “He just started watching it.” His son was great, so enthusiastic. He recognized me and he got real excited to come and meet me. I was like, Oh, that’s cool. His son’s going to be a fan. That’s awesome.