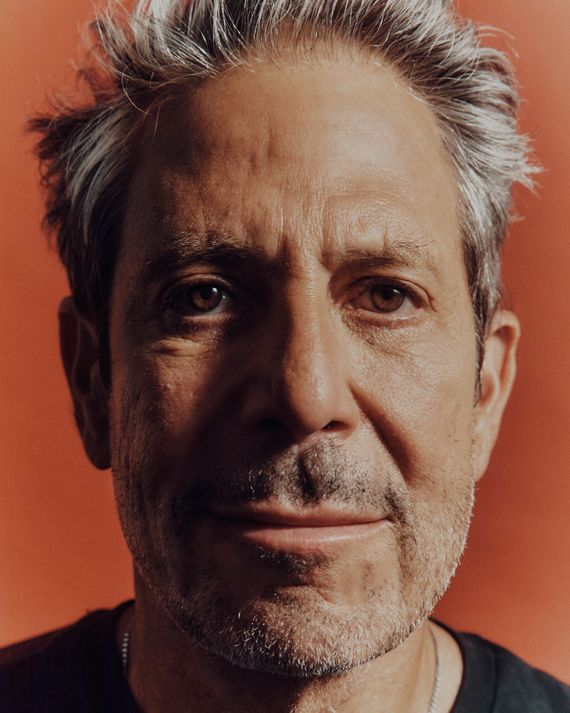

For about as long as any millennial has been watching television, Darren Star has been making it: Beverly Hills 90210, Melrose Place, Sex and the City, Younger, Emily in Paris. His hits span four decades and various business models in the medium — broadcast, cable, streaming — all known for their compulsive watchability. It’s possible that what he loves most about writing television is the act of starting a new show; once each one had found its legs, he often left to do it again elsewhere. Nostalgia doesn’t interest him. “I’m a shark,” he says. “I like to keep looking forward.” In person, the 63 year old is tanned and smiley, wearing a fitted black T-shirt and white jeans. At his suggestion, we have lunch at Union Square Cafe, a classic ’80s restaurant that hasn’t lost its audience. “As I always say, ‘You really only need one hit show at a time,’” he tells me.

You were 28 when Beverly Hills 90210 was green-lit. What was the original pitch?

I said that no one had written a show about teenagers from a teenage point of view. Movies like The Breakfast Club and even teen magazines had a level of acknowledgment about teenage sexuality and what their lives were like. There was nothing relevant on TV. It’s hard to imagine now, but it was the biggest long shot ever. Aaron Spelling at the time had nothing going on. Fox was this young edgy network. It was like, “Okay, try it.”

I was very involved from the pilot through the second year of the series. Aaron and I cast it together. I had very little control as a writer on films, but as a writer in television, I was suddenly involved in every aspect of production from casting to editing to music. To everybody’s surprise, the pilot tested through the roof. The first year, the ratings weren’t good. It was always on the verge of cancellation. I remember Aaron talking to the network, saying, “Just give us three more episodes.” He was a fighter for the show. It limped along until the reruns started to do better. Then it came back in the summer and caught fire.

The cast was not much younger than you. Did you feel like you had to learn to have authority? Did you party with them?

I wasn’t partying at all because the amount of work that went into doing that many episodes left no time for anything. I would look at them and think they were having fun and I wasn’t. I was just trying to keep my head above water. The thing about a network is they always kept you on edge a little bit.

Did the sudden popularity create more scrutiny from the network?

They scrutinized it because I’d written and directed this spring-dance episode at the end of the first season, where Brenda (Shannen Doherty) and Dylan (Luke Perry) have sex at their junior prom. When all these affiliates realized what they’d aired, a lot of them got bent out of shape. And it wasn’t just the fact that Brenda had sex but that she enjoyed it. When we came back for the next season, they demanded there was an episode where she had remorse. I was like, I can’t believe I have to write this. She had a pregnancy scare. She realized she was too young to have sex. But if you look at the first season, it’s almost like before the Hays Code. They weren’t paying attention. There were a lot of edgier episodes.

Were there other ways the network intervened?

Yeah, they had a lot of notes. Everything about sexuality was hard to deal with. Initially, they were like, “Where are the parents? Where are the teachers?” And I’m like, it’s not a show about parents and teachers. It’s a show about these friends who were there for each other, solving each other’s problems.

And were you doing Melrose Place simultaneously?

I was primarily writing 90210 heavily for the first 50 episodes. Then my main focus was Melrose Place.

Was it because the characters on Melrose Place were adults and you could be freer in terms of sexuality?

I was just really running Melrose Place. It was a 90210 spinoff. The problem with Melrose Place was, at the beginning, it inherited some of the baggage of the earnest 90210 storytelling. The ratings were really bad. It wasn’t until Heather Locklear came on that she unlocked something, maybe because she brought this Dynasty cred. She literally could not say “hello” without an agenda. I wanted to make it as addictive as possible. That introduced outrageous storytelling, like a very unhinged nighttime soap. I never thought of myself as someone who would write a soap, but I felt there was a sense of humor behind it. It was very self-conscious about what we were doing.

Would you consider it camp?

You can’t try to do something campy. Now, you can look at it and think, Was it campy? Maybe. But the other thing that accidentally helped Melrose Place work was the earnestness of those first 20 episodes in establishing these characters that were very grounded in almost a boring way.

The first episodes are very slice of life, almost naturalistic.

It was like you were invested in the reality of these characters that all these crazy things were happening to, because they didn’t start crazy. I think that is always the danger. Had everybody started at that high pitch, I don’t think the show would’ve worked.

How were you able to generate such a high volume of story? We’re talking 22-, 28-, even 32-episode seasons for 90210 and Melrose Place.

At the beginning I was shocked by the pace. But I loved the deadlines, the amount of action, the continuous production. To be writing and feeling like whatever I’m writing is getting made next week — I got addicted to that. You were forced to write without thinking too much about it. The more time you have, the more time you’re going to take. In a way, your ideas become more free flowing. You let ideas fall. You’re not censoring so many things. You take more chances. You’re trying things.

In the Melrose Place writing room, I pitched this idea: Marcia Cross’s character, Kimberly, initially died in this car crash. She disappears for like 17 episodes and then she comes back. You don’t know what happened, and she’s acting a little odd. Then she goes into her bathroom, pulls off her wig, and she has this hideous scar. I thought the writers were going to say, “That’s crazy,” but then somebody said, “Oh, my God. I love it.” You let your crazy ideas happen, because you need to create the story.

90210 became huge, and all of these relatively unknown kids became wildly famous. Did that change your relationship with writing the show?

I was always trying to divorce myself from how popular the show was. So much time was just focused on writing scripts, being in the editing room, getting the show out. It’s almost hard to imagine how popular it was. They weren’t just on teen magazines — there were many magazines devoted just to 90210. It was out of control.

How did it affect managing the set?

They were crazy.

There have been a lot of stories of that era from the cast, including memoirs, podcasts, and interviews. How do you view it in retrospect?

Everybody was a little off the rails. They were working 13-hour days, five days a week, year after year. I felt like the cast was in high school while they were doing the show. It did force me to be more mature. I remember directing an episode. Shannen wasn’t there. We were calling around like, “Where’s Shannen?” By the way, I adore Shannen; I love her.

Did her death cause you to reflect on your time working together?

She’s an incredibly special, dynamic person. I was thinking about Brenda and Shannen, and I feel like my career has been defined in so many ways by writing strong women. Shannen gave Brenda so much spirit and determination and complication. What she brought inspired me to write toward Brenda even more. She was herself an independent spirit who felt everything deeply. She captured something about being a teenage girl who really was a powerful girl.

I would like to hear more about that relationship. I don’t think you’re the first gay man to feel drawn to a powerful woman.

Or the first straight man. David E. Kelley wrote Ally McBeal. Woody Allen has written many women. Tom Wolfe has a book, I Am Charlotte Simmons. So you don’t have to be a gay man to write women. The Mary Tyler Moore Show was a huge inspiration to me. That was written by straight men. The idea that gay men write women is just not true. Not only is it reductive, it’s 100 percent not true. Because if you look at the great shows about women, they were by straight men, because people are people. That’s the job of a writer: to put yourself in the shoes of another character and imagine life from that point of view.

I hear you. I do think there’s a specific relationship between gay men and women, but I’m fine to let go of the identitarian stuff. What I’m more curious about is your relationship to that kind of woman.

Okay. I’m making that point for you because I feel like I’ve heard that before. It just feels like it’s not true. I have a lot of female friends. I have a mother and a sister, who I’m very close to, who are strong, smart, witty women. On my shows, the female characters come from a position of being an underdog. I’m attracted to those characters because I think women are very complicated. They’re funny; they’re expressive about their emotions.

You first met Candace Bushnell when she was writing about you for Vogue when you were doing Central Park West on CBS. Is that how you became friends and eventually created Sex and the City?

Yeah. When I optioned her little but very smart column in the New York Observer, I was so tired of the constraints of network TV. I was going to write either a movie or series that was on a cable network, where there were no restrictions in terms of content.

You wanted freedom.

Yes, I wanted 100 percent freedom. What’s ironic is I thought Sex and the City was anti-commercial. I thought people might misinterpret it and it could ruin my career. Like, they would say, “Oh my God. It’s too racy.” I felt like my peers would get it. It would celebrate, not demonize, sex. The whole age of AIDS made people gun-shy about depicting sex. It had a connotation of danger.

In terms of how frank the show was going to be, it was coming right after the Bill Clinton–Monica Lewinsky scandal. I really felt like, “America’s discussing blowjobs around their dinner table. They’re ready to see this show.” It was conversations I’d had with my friends.

Each of the four women came to represent individual archetypes with specific and varied relationships to sex, relationships, ambition, work, power. I think the fun was seeing those different ideas percolate against each other.

Yeah. I wanted to create these women who had different points of view. Samantha was a libertine, Charlotte was the rules girl, and Miranda was the slightly bitter working woman professional. Everything the show is should be in the pilot. The storytelling, how Carrie explores a question — “Can women have sex like men?” — how the women all have different points of view and really express who they are through that discussion. And in the end, how Carrie meets Mr. Big. Having done so many years of Melrose Place and 90210, I wanted to do this single camera film half hour where there would be a continuing storyline. Her story with Mr. Big was something that would be arcing through the show. Even sitcoms turn into soaps after so many years because when characters get developed, you want to see them have lives that are continuous. You don’t want to feel like their lives are resetting every episode. I was very conscious that Carrie and Mr. Big were going to be the spine of the show.

How did you know that?

This unattainable man and her yearning for love and relationship was something that was going to create the tension of the series. So that even if we did standalone episodes, you’d come back to this.

Carrie cheating in season three on Aidan with Big felt like a real turning point in terms of the ambition of the show.

It brought the show to another level. I really wanted a character that was going to make mistakes and be an anti-hero, to be able to love and hate her at the same time, see her make mistakes, understand her. It made the character way more complex. It brought up issues with her friends. Then it humanized Natasha because suddenly, she was a character that Carrie was hurting.

Were there characters you felt closer to?

Certainly Carrie. She’s a writer. I’m the writer. Not just that, but her neuroticism, her sense of humor, the way she looked at the world. There’s this sense in writing these characters where it’s about keeping a certain level of immaturity. You want to feel like, Yes, I’ve got wisdom, but at the same time, I can be connected to that younger side. I could write Emily in Emily in Paris because I can still connect to that girl in her late 20s; I can still tap into those emotions.

How have you kept that channel to youthfulness intact?

I don’t know. It’s not something I consciously try to do.

Do you do ’shrooms?

No, I’m weirdly not great at taking substances that make me feel like I’m not in control. It’s not through anything like that. I have the opposite problem: I have a hard time putting myself in the shoes of a character my own age. Except for Uncoupled. That felt very close to home.

Uncoupled tells the story of a 40-something gay guy (Neil Patrick Harris) who gets abruptly dumped by his partner of 17 years. Were you going through a similar experience?

I’d been through something like that before. But I feel like everybody has. It could be just the fact that I’ve been single at all ages of my life. When you’re single, you’re still in your 20s. It doesn’t matter how old you are. It’s all the same. Maybe that’s part of it. I’ve been in a number of wonderful relationships, but I’ve never had one ongoing long-term relationship throughout my entire life. When you’re on your own, there’s less of an anchor, so you’re forced to be more open to the world. Those feelings don’t change as you get older. I’ve been thrown back into those waters and been in touch with them. So that maybe unconsciously has informed things I’m able to write.

Uncoupled had one season on Netflix before it was canceled and then picked up by Showtime. You were supposed to shoot the second season but then Showtime canceled it too. What happened?

It just didn’t get the big numbers on Netflix. When it was going to go over to Showtime, we’d actually written all of our episodes for the second season. We were going to start filming after Memorial Day in New York. I wrote it with Jeff Richman from Modern Family. The second season was going to take off like a rocket, really. But Showtime just changed their strategy — I don’t think they’re doing half hours — and the plug got pulled in a surprising way.

Did you ever try to make another show with a gay protagonist before Uncoupled?

No. Uncoupled was not telling a show about the gay community. It was telling a show about these particular people that happened to be gay and this particular slice of life. You know what I mean?

Sure.

Sometimes I think the gay community basically says, “That’s not our story.” Well, no, it’s nobody’s. It’s sexuality. There’s many, many, many stories to tell people can relate to or not relate to.

Did you feel like that was happening with the show?

Maybe. You know what I think ultimately happened? I think people expected a gay show to be funnier and jokier. This was a show about hurt and emotions with gay people. I think when people hear about a show about gay characters, they think it’s going to be hilarious. It was funny, but it was dark and it had a lot of emotion in it. I’m trying to think about many dramedies about gay characters that aren’t joke-driven. This was a show that was emotion-driven about gay men being single at a certain age.

Do you think there’s a specific challenge with a gay audience that is harder to market?

No. I think it’s about a show with a gay leading man or woman breaking through to a wider audience. You need everybody. It happened with Will & Grace. It’ll happen again.

In 2000, you stepped down from showrunning duties on Sex and the City after its third season and became a consultant. Why did you leave?

In hindsight, maybe it just wasn’t working out the way I wanted it to. I said a lot of what I wanted to say, and I wanted to do other shows. I was given the option of staying on; I just wasn’t given the option of being able to do other shows while I was doing SATC. If I had stayed on 90210, I would’ve never done anything if I hadn’t moved on from that. It ran for ten years. I was a creatively restless individual. Three seasons felt like a lifetime. Maybe the shows I did right afterward weren’t huge hits, but they were shows I wanted to do. For better or worse, I like to take risks.

Is that still the case?

Yeah. That’s why I have more patience now. I really do.

You stayed with Younger until the end, right?

I stayed. It was also hard to imagine Younger happening without me.

Like network buy-in?

No, creatively.

How would you have ended Sex and the City if you had remained as showrunner?

Well, it’s never ended, has it?

Fair.

I’ll tell you what. I would’ve never had the creative interest to continue the journey. For all those that are doing it, I’m happy for them because they do have the interest. It gives me validation that the characters I created still have a life and the audience has an interest in seeing them.

So you’re not involved in And Just Like That …?

I’m not creatively involved.

Did you ever want to be?

No, I was busy doing Emily in Paris. Look, they rebooted 90210 and Melrose Place.

Nostalgia culture has a strong grip on decision-makers in Hollywood. Everything’s a redo or recycled IP. What do you make of it?

I think it’s terrible. I’d rather fail with a fresh idea than do a reboot. It feels like a product. It’s hard enough to do something the first time. I’m not saying And Just Like That … doesn’t have things to say. I’m differentiating And Just Like That …, which I feel is a continuation of the characters at a different time in their lives. There’s a relevance to it, no question. I’ve had three shows rebooted, and that’s amazing.

I want to return to the question about the series finale, because you’ve said that having Carrie ending up with Big was a betrayal of the show. What would you have done?

I’ll preface it by saying that Michael Patrick King was really creatively in charge that final season. He did an amazing job. Shows evolve and Carrie certainly evolved. But I always felt the show was never about a woman getting her man: That’s a traditional romantic comedy. It was about how women can define themselves 100 percent, that they didn’t have to be defined by marriage. But if that were the ending, I’m not sure the audience would’ve loved it. The show had a real audience-pleasing ending.

Can you tell me about what happened when you and Candace Bushnell had dueling shows come out: Cashmere Mafia versus Lipstick Jungle? At the time, the Times reported Bushnell and her friends felt betrayed.

That was an awful piece. Candace and I are very good friends. I mean, we had a rift over that, and I can go back and understand how and why it happened.

At the time I had a deal with Sony. Lipstick Jungle got set up somewhere else, not with me. Then separately, Gail Katz brought me an idea about four female friends based on her experiences at the Yale School of Management. I had committed to making a pilot with Kevin Wade, who loved the idea and he developed it. Then they both happened at the same time, and the press went to town, as they do, which benefited neither show. I learned a lot, because that was a misbegotten network experience: a lot of network interference, the whole pilot being re-shot and everything. Sometimes you have a learning experience when you have to say … “Creative differences.” It was terrible. I’ll probably never do another network show, but I don’t think people watch the networks anyway, so I don’t think that’s going to be an issue.

Grosse Pointe, the TV show you left Sex and the City to do, is an interesting one in your career. It’s a spoof about making a teen show that’s a lightly veiled version of 90210. Was there a catharsis in writing it?

Yeah, I had so much fun writing that show. It made me laugh, but satire does not work on network television. I think the show would’ve had an amazing life had it continued. I think it would’ve had a great, long life in today’s world on streaming.

Both Grosse Pointe and Popular, Ryan Murphy’s first show which was also an acidic send-up of teen show tropes, were on at the same time at the WB. It’s interesting that network executives wanted to do them.

On network television then, if not now, there’s a disconnect between what executives actually like and appreciate versus what’s going to work. And they liked it. They loved Grosse Pointe, but could they look at it with a cold eye and say, “Are the ratings there to bring it back?” When you look at cable or streaming networks now you can have a love for a show and keep it going. Whereas back then at a network, if the ratings weren’t there, love was not enough to keep a show going.

Is Netflix that much different now if the numbers aren’t there?

I don’t think so now. Maybe it used to be, but the streamers are starting to feel more like the networks used to. Unless the show’s winning an Emmy. When Fox canceled Arrested Development along with Kitchen Confidential, I’m like, “Well, these guys are canceling their Emmy winning show, so they don’t care about the quality.” The difference if you’re on a streamer or cable, and your show is getting critical acclaim and nominations, that is enough to keep it going. I developed and I produced the book Good Christian Bitches; I think if I had just called the show Highland Park, it would’ve been a hit. Seriously. Because the book was called Good Christian Bitches or GCB, I dug in.

You really think it was the title that did …

Oh, yeah. A lot of it.

Did you feel any trepidation doing Grosse Pointe given the Aaron Spelling of it all? You’ve said that he was “incensed” by it, particularly by the Tori Spelling character (played by Lindsay Sloane). Interestingly, I thought that character was kind of sweet.

Yeah. Look, just like French people get offended by Emily in Paris, sometimes it’s hard to laugh at yourself. There was a character in Grosse Pointe that was an avatar for me. If you watch what he does every week, he’s running scared, freaking out, anxious. It’s like having their head spinning with network notes, trying to please everybody. It’s not the most flattering portrayal, but it was how I wanted to write. You want to get as much comedy in there as you can. It wasn’t a documentary. It was a satire. I never wanted to offend anybody.

I think that all comes through. I was just curious about the real-world implications of making a spoof about your former workplace.

When shows push people’s buttons, I don’t think that’s a bad thing. Emily in Paris is the most innocuous piece of entertainment and it pushed people’s buttons. I’m like, Wow, why? How are people taking this so seriously? Or finding things in there that feel somehow offensive.

When Emily in Paris premiered in October 2020, there was backlash that it was out of touch with the real world and a fantasy about privileged people. I’m curious what you think about that criticism now.

Well, you know what? I was intending to make a show that was aspirational. I wanted to create an entertaining show about an American in Paris. When I was 19 years old, I spent the summer in Europe backpacking. I fell in love with Paris then. If there’s one thing the show could inspire people to do, it would be to go to Paris. Beyond that, I have zero interest in what critics might say. I’m not quite sure what the question is in that regard.

Well, did you feel the criticism had any merit? One of the critics was Deborah Copaken, a former writer on Emily in Paris. She wrote an op-ed about how Emily in Paris wasn’t tackling thornier subjects like sexual assault.

I’m sorry she didn’t like the show she was writing for, but I did exactly the show I wanted to do. I care about the audience. Literally, I don’t care about critics. I think a lot of them might’ve changed their mind, but I don’t care. It was the most successful half-hour Netflix ever produced.

I don’t want to paint a black-and-white picture either. What I’d like to discuss is this question of whether the show should take on weightier issues. Looking at the development of the show, it was interesting to see a story line about sexual harassment introduced last season with the character Sylvie (Philippine Leroy-Beaulieu).

No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. The show was what the show was in the first season. It wasn’t about taking on weighty issues. We’re doing it now because we’ve set the table for it. But in season one, the show was completely from Emily’s point of view. It’s very simple. It wasn’t about the other characters. Then as the series evolves, it’s like, Okay. Now I want to start telling stories about these other characters. That’s how a lot of shows evolve. You know you have a show that’s working when you want to tell stories about other characters.

Were you worried about upsetting the balance of the show in terms of fun and seriousness?

Yeah. We worked a lot on that story and there was a version of the script where it was really front and center. The way we did it didn’t overtake the show, but we were still able to tell the story.

What were you hoping to do with the upcoming season of Emily in Paris?

Emily is not a fish out of water in Paris anymore. The show has evolved past that initial premise. Emily and Gabriel was such a romanticized relationship that it becomes a little more real. I wanted this show to get out of the love triangle rut — I wouldn’t say rut, but where it had been. I think it had been circling the same characters. There’s new characters. There’s a new city that comes in: Rome comes into the second half of the season. And it’s airing in two parts.

You’re doing the Bridgerton drop.

They are. Netflix is doing it. I’m not doing it. Yes.

Do you have a preference?

I don’t know. I think it’s going to work just in the sense that people will want to come back for the second half. They want to promote the show in two different months. If you have churn, you have people that’ll sign up for a month for Emily in Paris, but now they have to sign up for two months. For any given show, it keeps engagement higher.

How long would you want to do the show?

I can see two more. Beyond that, I’m not sure.

Do you feel vindicated by its success? To your point about travel, I assume part of the popularity was because we were all stuck at home and watching Emily in Paris was a way to vicariously do so.

Yeah. I feel vindicated that the first season of the show got such bad reviews and that we were also nominated for a Golden Globe and an Emmy Award as Outstanding Comedy Series that year. If you’re going to care about those things, I care about that validation more than I care about what the critics think. I can’t worry about what the critics say because then I probably wouldn’t have a career. In that respect, I put blinders on the same way I would put blinders on audience comments. It’s like, “Okay, everybody has an opinion.”

Interestingly because of Netflix, you get the feedback in terms of the audience numbers right away. They share a lot of numbers and statistics now. We knew the show was huge from the beginning. Everybody said the show was popular because everybody stayed home to watch it during COVID, but the audience grew in seasons two and three. It’s wonderful to have a hit show, but it’s not my only parameter or measure of success. Younger didn’t get that. It wasn’t on Netflix. It was on a small network. I’m super proud of that show. I love it. It’s going to be on Netflix in October. I’m really happy about that. It’s going to see a bigger audience.

Do you think it’ll get the life it deserved?

I hope so. It got fantastic critical reviews. The audience that saw it loved it, but it’s not a massive hit like Emily in Paris. My point is I’m as happy and proud of that show as anything I’ve done. I didn’t know Emily in Paris was going to be a hit. I did it initially for the Paramount Network. They were amazing partners and they said, “Okay, we’ll see if we can sell the show to a streamer.” We took it to Netflix, and that all worked.

Were you pushing for that decision?

Yeah. I really was pushing for it because I felt like the Paramount Network at the time was very driven by Yellowstone. It was a cable network, and I just felt like the show wouldn’t find its audience on that network.

Emily has cleverly been able to integrate real-life brands into the narrative by virtue of Emily working at a marketing agency. This season you continue the Ami campaign. There’s Vestiaire Collective. In the past you’ve had McDonald’s, McLaren, and others. I assume you have brands pitching you.

Yeah. I definitely have brands that would like to be involved. Here’s the thing: They can’t have any input into the story. In the first season, we approached Cartier to do a party. Cartier was like, “No, we don’t want to do it.” We changed the name. It doesn’t matter that much. It’s fun when we can use an actual brand because it adds a sense of reality. But if a brand doesn’t want to participate, we fictionalize the brand. RIMOWA was fantastic. They came in with the luggage and Pierre’s face on it, and it worked terrifically. Whether most of the audience even ever heard of RIMOWA, I don’t know. If it was a fictional brand, the story would be the same.

Does it become part of the production budget?

Yeah. It’s value added. It helps our budget. It helps me do the show I want to do. It’s fun when it works with the story. I loved McDonald’s because I remember weirdly being so happy to find a McDonald’s in Paris and having that American experience in Paris. The fact that it’s based in Chicago where Emily’s from was great synchronicity. It was a brand that represented being an American in Paris: how the French react to it, how they love it and hate it the same way they love and hate Emily.

Was it difficult to get McDonald’s onboard?

No, they wanted to be.

Have other brands turned you down?

We wanted Peloton at one point to be involved. They didn’t want to do it. I think they might’ve gotten burned by another show, so we fictionalized them.

You weren’t going to kill off a character on a Peloton bike?

[Laughs.] No.

*An earlier version of this piece misspelled Jeff Richman’s name. It also mistakenly noted that Star was very involved with Beverly Hills 90210 from the pilot through the first year of the show. He was in fact involved through the second season.

More conversations

- David Lynch on His Memoir Room to Dream and Clues to His Films

- Willem Dafoe on the Art of Surrender

- Emily Watson: ‘I’m Blessed With a Readable Face’