Every time a show you love gets canceled, it hurts. But the cancellation of David Milch’s Deadwood in May 2006 hurt worse because no one saw it coming, including the main players.

Milch’s HBO anti-western debuted in March 2004 to mostly rave reviews and excellent ratings, thanks in large part to having season five of The Sopranos as its lead-in. The numbers for season two, which debuted almost exactly a year later, weren’t as strong since Deadwood was now leading off the night, but they were still substantial enough to rank among the cable network’s most popular dramas. There was no reason for anyone inside or outside of television to think it wouldn’t run five seasons, as Milch wanted. HBO had lured the powerhouse writer-producer of Hill Street Blues and NYPD Blue with the promise of creative control, a generous budget, and nearly unlimited content restrictions, and set him up at Melody Ranch Studios outside of Los Angeles with one of the largest freestanding sets in TV history, re-creating the eponymous mining camp in all its muddy glory. The show even had an internal okay to start production on season four when the axe fell.

The series of events leading to its cancellation long remained cloudy; key participants were prone to eliding unflattering details in the telling, or shifting blame onto others (and in some cases, themselves) for personal reasons. But in the making of The Deadwood Bible, a definitive account of David Milch’s life and art, I was able to nail down the details. The book — which was produced with Jeremy Fassler, who helped research the biographical section of Bible from which this excerpt was drawn — tapped into a town’s worth of collaborators, including Milch’s family, key actors, producers, writers, and crew, to tell the complete story of the show.

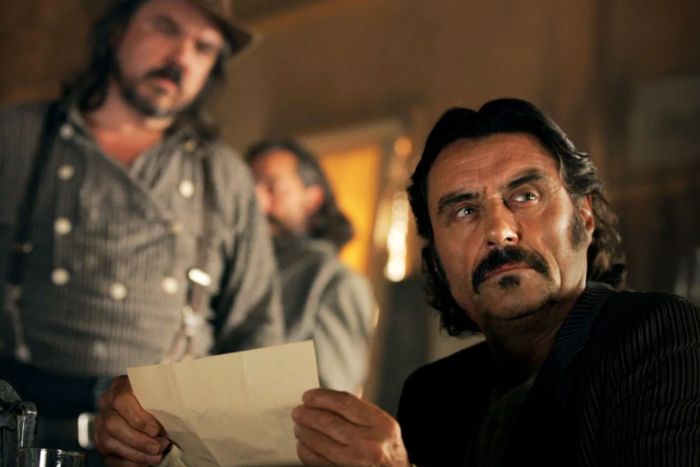

There are key details you should know before reading the section below, which begins the day the show’s cancellation was set in motion and ends with the publication of Deadwood: Stories of the Black Hills, a making-of book by Milch that was intended as a companion to season four but ended up carrying a sad postscript. (There is also mention of plans for two Deadwood movies that ended up becoming just a single feature film more than a decade later.) The dramatis personae of the excerpt include Milch and HBO executive Chris Albrecht; Deadwood cast member and Milch confidant Dayton Callie; Milch’s wife, Rita, and daughter, Elizabeth; and various actors, producers, and writers, including co-stars Timothy Olyphant, Ian McShane, and W. Earl Brown and executive producer Gregg Feinberg.

Excerpt from 'The Deadwood Bible'

Deadwood died on a Friday.

The date was May 5, 2006. It was late afternoon in Santa Monica. David Milch was sitting behind his desk in his office at Red Board opposite Dayton Callie, talking about screenwriting, when his secretary told him that Chris Albrecht was on the phone.

Callie didn’t hear Albrecht’s side of the conversation, but said the talk with Milch was brief; it focused on the number of episodes Milch would need to do a fourth season; it was punctuated by Milch’s “Mm-hmms” and “Nos.” and it ended with Milch saying, “Okay, fuck it — why don’t we do none.”

Said Callie:

When he hung up, I said “What the fuck was that?” And then he said “They want me to do eight fucking episodes. I told them to fuck off.” I said “I know you told them to fuck off. But why don’t we do fucking eight, and then fucking say we need fucking four more? Why the fuck do we gotta quit like this?” He said “No, no, no — I don’t like that.”

Milch told Callie he needed space so he could call the cast and fill them in on the latest developments, starting with Timothy Olyphant. On his way out, Callie told Milch, “All right, they’ll work it out. They’ll work it out. This is fucking stupid. We got a nice show, a good show.’”

Albrecht didn’t remember Milch’s “Okay, fuck it — why don’t we do none,” but definitely remembered Milch telling him, “We can just not do a fourth season and end the show where it is now.” The HBO exec said he replied, “That’s not what I’m saying to you. David, just think about this. We can work it out. If you come back and tell me ‘This is what it’s gotta be’” — meaning more episodes than Albrecht had just offered him — “we can figure it out.”

John from Cincinnati was also part of this discussion. Albrecht said he had started the call by telling Milch he loved the pilot script for John and was eager to begin production on Season 1:

I said, “We would like to get on to the next thing, and you can’t really do two [shows] at once. Here’s where we are with Deadwood: instead of doing 12 episodes, do you think maybe we could finish up the series in maybe six?”

And he said “Look, if you guys want to not do the show, I’m not one of those guys that thinks I have to finish it. We can just end it.”

I said “David, that’s not the conversation I’m trying to have now. What I’m saying to you is, maybe there’s some in-between where we can do the right thing for the show, and then go on to the next thing for you.”

And then I could tell he was struggling. It was the weekend, and I said, “David, just think about it over the weekend. Let’s talk about it next week. If you come back to me and you say ‘It’s gotta be 12 episodes,’ we’ll do 12 episodes, because that’s at the heart of who we were, you know?” I wasn’t going to end this great experience with a bad situation.

I’m telling you, this is the story. A lot of things I’ll say to you I don’t remember, but I remember this story. What I just told you is what happened. We liked other stuff, we wanted to move on, we wanted to find the right ending for David, we talked to him about some other solutions besides a full season, he got upset.

Milch later explained that he felt a fiduciary responsibility to his cast to do 12 episodes, the number of Deadwood episodes the Melody Ranch gang were used to making. Therefore, he could not accept substantially less than 12. He also thought it was better to let everyone know that he and HBO were having differences, and they should start thinking about backup plans in case the worst occurred.

“He got very nervous that people were going to get screwed if [the renewal] didn’t go through,” Elizabeth Milch said. Albrecht added, “David knew that Tim Olyphant had just put an offer in on a house.”

At this point you, the reader, have probably noticed that accounts differ as to whether Albrecht initially offered Milch six episodes or eight.

Albrecht started his Deadwood Bible interview by stating that he had offered Milch six, as quoted above, but revised his account to say that it might have been eight, as Callie said — or that it might have been ten. Everyone previously interviewed about Deadwood’s cancellation who knew this part of the story confidently said that Albrecht offered Milch six episodes, and that number appears in media reports over the next decade-plus.

There is also consensus that Milch might have settled on six because people who knew him would understand why he’d felt insulted by a half-season order and reacted intemperately. Six was an affront if you were him.

But eight? Eight was something else. You could build on eight.

Albrecht, however, insisted that the exact number was unimportant, because the conversation was supposed to be a starting point, not an ending:

Maybe I said “If it’s not six, maybe it’s eight.” But I also said “David, just think about this. We can work it out. If you come back and tell me “This is what it’s gotta be,” we can figure it out. Any time you say to somebody “six” and they get upset, and you say “How about eight?” a halfway intelligent person would say, “I bet I could get ten.” Right?

But here’s why I’m telling you that I know the truth: because it wasn’t six or eight or ten. It wasn’t as if David said “eight” and hung up the phone. It wasn’t David hanging up the phone. It was David picking up the phone then, and calling Tim Olyphant.

That was the problem. OK? He decided that it was his duty to call Tim Olyphant and tell him that HBO wanted to cancel Deadwood and maybe he shouldn’t put the offer in on the house. By the time the weekend was over, the trades had it that we were cancelling Deadwood, because I’m sure what happened with Tim is he called his agent and said “Holy fuck, they’re cancelling Deadwood!”

David should have just shut up and calmed down over the weekend. We would have talked about it on Monday, and we would have come to a solution that would have resulted in a Season 4 and an ending to the story, or the series, okay?

But he did what he did, and it got out of our hands.

We never canceled the show. The show canceled itself.

HBO knew they had a public relations nightmare on their hands. Even though nobody at the network had said “Deadwood is canceled,” there was a perception that wheels were in motion.

Behind the scenes, executives started sorting themselves into pro- and anti-cancellation camp, with the pros insisting the ratings performance didn’t justify its budget. (Deadwood was the fourth-highest rated HBO drama of 2005). Albrecht has never given a clear picture of which outcome he would have preferred. Strauss was pro-renewal (within limits), as she was and would continue to be Milch’s champion. In Tinderbox, HBO’s co-president of legal affairs Hal Akselrad said that his fellow executive Richard Plepler “drove hard to cancel Deadwood.”

Milch, for his part, realized his impulsiveness had rung up the curtain on another career disaster — the worst yet. He offered to go to New York and try to work things out, said Rita and Elizabeth Milch. There was at least one plane trip there, possibly early in the week that followed the May 5 conversation.

On Thursday of that week — May 11, 2006 — Variety ran a story headlined, “Is Deadwood Riding Off Into the Sunset?” The summary beneath the headline said: “HBO confirmed Thursday afternoon that it had let lapse the options on the cast of the grisly Western. Decision frees the actors of any further obligation to the show, which has yet to be renewed for a fourth season.”

If Deadwood wasn’t dead yet, it sure was looking green around the gills. The show would expire due to inaction, as well as a desire of key participants to move on rather than try to unring a bell.

Leah Cevoli went through a deep depression that summer. One day in August, she called her mother to explain the situation. “My mom said, ‘Isn’t this around the time you would have started back on Deadwood?’ I said ‘Well yeah, mom, I guess it is.’ And she said ‘Well honey, these past three years of your life, this was your job. Of course you’re missing it and feeling depressed about it.’ And I was like, ‘Yeah. Wow.’ She was right.”

“It’s a tragedy that it ever went off the air,” Ian McShane said, “but that was also partly David’s fault, and partly the powers that be at HBO at the time. It was a clash of fucking egos as well as everything else. The reason it went off was because of human failure.”

Cast, crew, and fans were despondent. Some were angry. As McShane said, there was plenty of blame to go around — although Fienberg would later express skepticism at Albrecht’s narrative of the clusterfuck, because to his mind, it represented an abdication of his and Strauss’ executive responsibility.

“Do you think if David Chase had ended a conversation about doing a sixth season of The Sopranos on a Friday by going, ‘Fuck it, how about none,’ that they wouldn’t have called him back immediately and said, ‘Wait a second, let’s talk about this and see if we can work something out’?” Fienberg asked. “Let’s not let HBO off the hook here.”

Albrecht’s description of what happened after the fateful Friday call doesn’t rule that possibility out, either:

Some [agents] might have called us after that and said, “Well if you’re canceling the show, we need to know, because my client needs a job.” And we certainly were never gonna screw somebody over. That’s why I said it just started to fall apart, because once shit is out there, now I’m in the spot of, “Well, I gotta order the show.”

It was like David picked up his ball and went home. And you know — We’re like: Okay. I guess it just kind of spiraled into a sad, unfortunate, unnecessary result, which was never anybody’s intention.

So, like I said, I don’t remember “How about none!” and hanging up, but maybe he did. Sounds like something David would say. But I stand by my story, because I know it’s true.

On June 11, 2006, the New York Times published a story titled “Deadwood Gets a New Lease on Life.” It offered a boiled-down account of the passive cancellation and its fallout. It spoke of a fan petition to bring back the series and an “open letter” to the network placed in Variety by savedeadwood.net. Both threatened cancellation of subscriptions.

“I’ve always known that the support for this show was not a mile wide,” Milch said of fan efforts to save the show. “But it was a fathom deep.”

Milch’s comments made it seem as if ending Deadwood was his decision, made because he didn’t want the show’s artistic integrity to be compromised. “It seemed to me that some sort of partial order for the show would make it impossible to do anything but superimpose all sorts of interpretations that would deprive it of its own emotion,” he said. ‘The viewer would come to it with all sorts of second agendas, and I didn’t want to do that.”

The lede, however, was buried far down in the piece: Albrecht, Strauss, and Milch had reached an agreement to end the story in 2007 with a pair of two-hour Deadwood films. Jody Worth believes this was the result of Milch’s damage-control trip to New York.

But nothing ever came of the announcement, and later, Fienberg questioned whether HBO was ever serious about it. His producer’s brain told him there was no financial advantage to doing it that way. A pair of two-hour movies — four episodes, basically — would have been at least as expensive as a partial season, given the costs of restarting and breaking down a canceled production, and luring back cast members from other projects.

In November, 2006, Milch published his Deadwood tie-in book Stories of the Black Hills, written during Season 2 and containing copious detail about Season 3. It was clear to anyone who paid attention to language and tone that everyone who contributed writing or interviews to its pages had assumed they were working on a show that would continue.

The only discordant element was a one-page statement by Milch that appeared at the very end — jumping off from an announcement that, by the time of publication, was already starting to seem like a pipe dream:

Next year, in lieu of a fourth, twelve-episode season, Deadwood will end with two two-hour specials. Probably I had too much to do with the process to offer any fair-minded account of how that decision was come to. I’ll take that as pretext for staying with vapid generalities. Here is an example: “There are no enforceable guarantees about anything that really matters.”

I’ve been quoted as saying I had a plan to end the series at the end of a fourth full season. As a sociopath, I answer the questions of interviewers to achieve an impression of cogency and farsightedness rather than hewing slavishly to the truth.

The truth is, I never had a master plan for Deadwood. I know good stories about many of the historical characters in the series that would take them through another twenty-five years, and good ones, too, about the characters I’ve made up. But as I’ve said here, I work moment-to-moment; this includes acknowledging the variability of opportunity each moment affords. The present moment appears to exclude the twenty-five year alternative.

The two two-hour specials will be a good way to finish the series. The first thirty-six episodes took an Aristotelian approach to dramatic structure—more-or-less, each story took place in twenty-four hours. This seemed to me in service to creating an atmosphere of ordinariness, no matter how disjunctive with the viewer’s idea of ordinariness the events portrayed may have seemed. These last two telefilms will deal differently with time.

If I’ve already said in these pages before that Mister Warren called Time the secret subject of every story worth telling, I don’t mind ending by saying it again.

The Deadwood Bible and companion works are available exclusively at mzs.press.