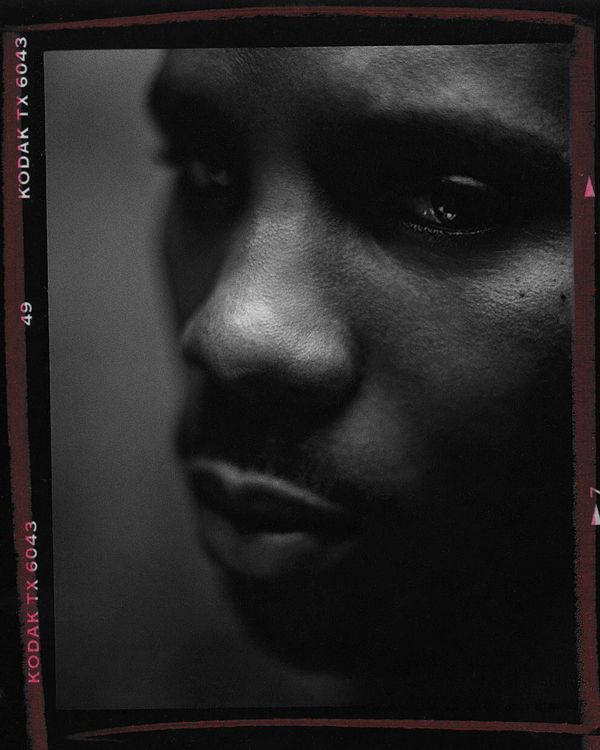

DMX seemed almost invincible. On record, onstage, and in film, he displayed an almost superhuman intensity. His songs served elaborate, believable threats: “I keep my slugs hollow, keep families with sorrow / Keep motherfuckers like you not seein’ tomorrow.” During his tenure as a legitimate action and gangster movie star, he depicted resourceful anti-heroes beating back seemingly insurmountable odds. Tommy from Belly runs afoul of religious leaders and drug dealers in two different countries and makes it out alive; Cradle 2 the Grave’s bank robber Anthony Fait cracks safes and takes down an international crime syndicate all to save his daughter. DMX struggled, but he persevered. He stumbled, but he got back up. In reality, though, he dealt with more and worse adversity than any single person should have to bear. What we saw was a man coping, a man hurting and transforming pain into usable strength. If he seemed endlessly energetic, consider the price of the fuel. As we remember the late Yonkers legend — who passed away Friday, April 9, at the age of 50 due to complications from a heart attack brought on by an apparent overdose — it’s just as important to grasp the far-reaching systemic failures that played into the life that he led, to save others.

The early chapters of 2003’s E.A.R.L.: The Autobiography of DMX recount a tale familiar to anyone who grew up in places where the nation’s bureaucratic authority seems to fail, around people whose needs always seem to come last, where regime change feels cosmetic because no president, senator, mayor, or governor raises your bottom line. In public housing, you see the best and the worst of people. There’s love, camaraderie, and music in rec-room birthday parties, in concrete cookouts, in block parties on the weekend. Lounge on stoops and listen through walls, and you might hear and see too much. You might know the unmistakable glint of sunlight bouncing off of a steel handgun produced in broad daylight in a place where you’d least expect it. You might come to meet the mild-mannered child whose parents only seemed to speak in open hands and electrical cords, the “bad” child who left “to see family” for months at a time and came back rougher every summer, the smart one underserved and under-engaged by public school, the beloved neighborhood figure growing wiry and thin and drawing rumors of clandestine habits. DMX was one of us, all of us, really. He commanded respect as much for the brilliance of his craft as for navigating street life adeptly enough to get out unscathed, a folk hero as much as a rapper. He hustled his way out of the projects, out of child abuse, out of a lack of opportunities. He wasn’t just a celebrity; he was proof that it was possible for everyone else downwind to survive without compromising their beliefs.

The genius of DMX as a writer and a performer lay in his ability to repackage the burdens of Black inner-city life in art that was vibrant and lively even in darkness. 1998’s “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem” serves its threats and aches in the form of skittering nursery rhymes: “N - - - - wanna try, n - - - - wanna lie / Then n - - - - wonder why n - - - - wanna die / All I know is pain, all I feel is rain / How can I maintain with that shit on my brain?” 1999’s “Party Up (Up in Here)” turns crushing pressures and a failing resolve into a rowdy club banger. New York street rap grew coarse in the late ’90s in response to the still-awful prospects of success in an era where, for some Americans, the economy boomed, but for the rest, the shortsighted scope of the Clinton welfare reform program (which, for the sake of bipartisan compromise, placed time limits on benefits and stiffened work requirements, creating paths to work for those able to climb the ladder but leaving the rest assed out down bottom), racist overpolicing, and three-strikes laws made it possible to go away for life without ever committing a violent crime. Suddenly, the grim realities DMX portrayed in early ’90s songs like “Make a Move” and “Born Loser” became prescient. He didn’t score a hit until his late 20s (like Jay-Z), but when we caught on to his work through “Get at Me Dog” or his appearances on the LOX’s “Money, Power, Respect” and LL Cool J’s “4, 3, 2, 1,” X found himself at the peak of his abilities and in the center of the moment. In the stretches at the turn of the century where he was arguably the biggest and best thing not just in New York but the country at large, he didn’t forget his origins or the difficulty shaking the history of pain and poverty he felt growing up. On the top, he didn’t dress flashily or turn into a kingpin on record. He stayed at street level speaking on street issues. He talked about how hard life was and still could be, not how good it got.

It’s all over the music, how unlikely and unbelievable that trajectory felt. At his peak, DMX was engaged in a tug-of-war between heaven and hell, and weighing his options with coaches from both teams. He philosophized about the rewards for doing good in “Fame,” from his 1999 sophomore album …And Then There Was X: “Now if I take what He gave me, and I use it right / In other words, if I listen and use the light / Then what I say will remain here after I’m gone / Still here off the strength of a song, I live on.” Frequently, on cuts like “Get It on the Floor,” from 2003’s Grand Champ, X grappled with dark forces: “And you motherfuckers wonder why I start shit / ’Cause when you look in my face, you see that hard shit / ’Cause I done been to hell and back, I ain’t with sellin’ crack / I’d rather rob a n - - - -, leave him with a shell up in his back.” On his 1998 debut on Def Jam, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot, he bargains with the devil in “Damien,” then asks for guidance and absolution in “The Prayer” and “The Convo.” He recast the ups and downs of hood life as Gothic horror and Shakespearean drama. He pondered the question of whether we ever truly escape from the circumstances of our births, whether or not our past trauma lies perpetually in wait to create havoc in our present. Death comes up a lot in the music of DMX, as it did with figures like 2pac, but it isn’t, as has often been suggested through the years, proof of a gift of clairvoyance. Stats aren’t on our side, and we’re keenly aware of this. “We wasn’t s’posed to make it past 25,” Kanye West’s “We Don’t Care” goes. “Joke’s on you, we still alive.” “All of your young life, you’ve seen such misery and pain,” Donny Hathaway sang to his “Little Ghetto Boy.” “The world is a cruel place, and it ain’t gonna change.” “If I don’t fly, I’ma die anyway,” X’s “Let Me Fly” promises. “I’ma live on, but I’ll be gone any day.”

For a man whose journey to success included many years as a bold, open-faced stick-up kid, and whose music gave voice to the deepest, darkest thoughts it is possible for a man to have, DMX paid his karmic debts back in spades. He inspired fans with music about being true to yourself and noble and loyal to the people who stick with you, no matter what side of the law you operate on. X mentored the younger members of his Ruff Ryders label like Drag-On. He looked out for children who, like himself, were dealt impossible hands. The many stories of charity work at places like the Children’s Village, the school for troubled children he was sent to in his youth after disobeying and running away from an abusive mother, and visits with children with AIDS in his free time reveal a man dreaming of a world that doesn’t create the experiences that would transform a young Earl Simmons into the Dark Man. (There are those who found X’s good-natured, light-hearted moments jarring against the uncompromising brutality expressed in his music, and the more lurid instances of sexual violence and homophobia peppering the catalogue are reason enough to feel that way. But morality is a world of often jibing alignments, not a sliding scale, where several things can be true. This music can be coarse and offensive and also inspirational. And it’s fine to feel conflicted, or even to not and just never engage.) But in moments where DMX’s demons got the better of him, the grace that he extended to the disadvantaged and the less fortunate wasn’t necessarily reciprocated. Perhaps it is the price of playing the unflappable, unkillable gangster that we thought DMX could handle more than anyone should. Maybe we put too much faith in his resilience. Whatever the case, we didn’t take his suffering seriously enough. Instead, jokes were often made at the expense of his and others’ addictions, thanks to the dubious crassness of that time and our conditioning with regard to substances.

The way we think and speak about hard drugs is tethered ineffably to the extreme and quite literally often cartoonish portrayal of use and users perpetuated in the heat of the War on Drugs. You came to believe that a person made a deliberate choice and concerted effort when they dabbled in substances, and this made it easier to grasp harsh charges for selling and possession, to push addicts off of public assistance, to suggest an underclass of citizens had earned its misfortune. DMX’s life story illuminates the lie in the bootstraps logic and the systemic oversights and failures that hinder the growth of children raised in “bad” neighborhoods. His hometown of Yonkers — split down the middle by the Saw Mill River Parkway, west of which families of color resided in low-income housing, and east of which white families enjoyed public parks and golf courses — was a hotbed of racial divisions where segregation in schooling and housing situated students of color in worse conditions than their Caucasian counterparts, where the more affluent residents fought tooth and nail against development of affordable-housing units on their side of town. In these schools, X, a smart but troubled child who’d later reveal he’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, presented a puzzle they could not solve. He bounced from institution to institution, feeling unwanted and misunderstood, believing that everyone else had given up on him. His first experience with crack came from a laced “woolie” blunt given to him as a teenager by a mentor who didn’t warn him of the risks. This flies in the face of the too-convenient messaging we’ve received about how people “end up in the streets.”

You can argue that DMX chose crime at various points in his journey, but you have to account for all the times people who should have been looking out for him failed him. You cannot argue that he chose crack. His life’s a testament to what finds you when you’re left by institutional neglect and cultural rot to your own devices, and the arduous efforts required to even your odds. Most of the millions hurt by broken systems never make the news; they walk the harrowing path to recovery, or they look out at us through laminated prayer cards, frozen forever in a moment of anticipated promise. DMX’s death should inspire us to rethink our flip and puritanical attitudes toward drugs, users, and addicts, and also to call on the music industry to do better by the artists who keep the lights on. Too many musicians give their all to the game only to land in dire straits when, years later, they become a burden. Too many legends lose their homes and their lives too early. Our elders are worth more than what they’re able to produce for us. Each light that blinks out is a reservatory of history and culture gone from us forever. How many more will it take to break the cycle?