Nineteen-year-old Texas rapper Tay-K was sentenced to 55 years in prison this summer for his role in a 2016 robbery that left the intended victim shot to death in his own home. Tay-K’s signature song “The Race” documented life on the run in a three-month stretch where he and a friend ditched their ankle monitors and skipped town. Florida’s YNW Melly awaits trial on two counts of first-degree murder. Melly stands accused of arranging for two associates to be shot, then driving them to the hospital afterward; his hit “Murder on My Mind” holds eerie resonance. South Florida rhymer Kodak Black is serving almost four years on gun charges. Baton Rouge’s NBA Youngboy is on house arrest after a roadside incident where his girlfriend was shot, and an innocent bystander was killed. Youngboy beat a murder charge in 2017 and has struggled to keep the terms of his probation. Brooklyn’s Tekashi 6ix9ine awaits sentencing on federal racketeering and gun charges and seems set to receive a lighter sentence for his very public cooperation with law enforcement.

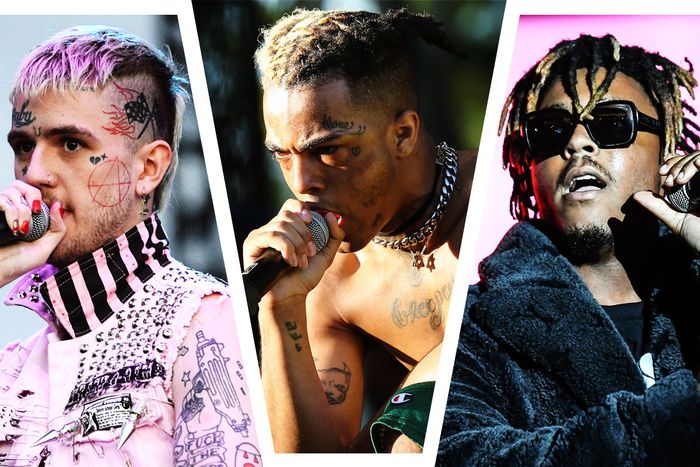

In L.A., 03 Greedo is serving a 20-year sentence for guns and drugs found in a 2016 traffic stop after police claimed to smell marijuana wafting off the vehicle, and Drakeo the Ruler beat a murder case this summer that attempted to use his lyrics as evidence, but remains in solitary confinement as local law enforcement attempts to prove that he is a gang leader. All of this is happening as fans still reel from the jarring losses of Mac Miller, Nipsey Hussle, Lil Peep, Fredo Santana, XXXTentacion, and many others. If you’re a fan of a certain age, there could be as many as 15 to 20 voices in hip-hop you sorely miss right now. That feels like a crisis. The question of the moment is the question of the decade: Are things just always bad, or are they historically bad?

The urge to pawn these events off as some catastrophic fault in the morality of a whole generation is strong. The tragic death of 21-year-old Juice WRLD this weekend reopened terrible old conversations about the relationship between rap music and drugs, and a shift from narratives about young men and women peddling illegal substances to stories about partaking. “I’m accustomed to artists talking about selling drugs,” journalist and sports commentator Jemele Hill tweeted on Monday, “but so many of them now seem proud to be known as hardcore users.” The argument, which, in fairness to Hill, predates the tweet by many years, says that drugs were prevalent in ’90s hip-hop, but songs about weed and booze didn’t hurt people the way the big Percocet, promethazine, and Xanax anthems of this decade have.

On a pharmacological level, sure, “Crumblin’ Erb” and “Gin and Juice” didn’t set as bad of an example as, say, “Mask Off,” and its chorus of “Percocet, molly, Percocet,” may have. There’s greater danger in pills and powder than puff, puff, pass, but it’s the wrong way to approach the matter. The substances of choice may have changed, but the animus for using hasn’t. It’s still hard to get by in disadvantaged communities. That pushes people to greater lengths to make a living. Greater lengths lead to deeper lows. Deeper lows push people to seek greater highs. (If we’re being honest, music about drugs by artists like Future that gets accused of “glorifying” use is often only speaking to the complexities of this causality. Future rarely revels in the codeine, the perkys, and the xannies. He uses them to cope, and it sounds like he hates it.)

The nearness of harder drugs is as much a story of personal choice as it is of the lay of the land. You can’t talk about drugs in rap without discussing drugs in America at large. There’s an opioid crisis, and coke, lean, and meth are around every corner. That isn’t the fault of any rapper. This generation didn’t invent pills, powder, or lean. They aren’t the first to introduce them to hip-hop. 80s and ‘90s stars from Flavor Flav, DMX, and ODB to Bobby Brown and Whitney Houston dabbled in hard drugs, though admittedly it wasn’t the focal point of their music. Texas rap lost legends in DJ Screw, Pimp C, and Big Moe in the aughts from complications believed to be tied to promethazine use. The Texas rap veterans were far from the first to dally with codeine. As a 2005 Houston Press article pointed out, southern folkie Townes Van Zandt’s 1968 classic “Waitin’ ‘Round to Die” ends in a chilling verse: “I got me a friend at last / He don’t steal or cheat or lie / His name’s codeine, he’s the nicest thing I’ve seen / And together we’re gonna wait around and die.” An honest conversation about drug use in music has to see it as a continuum and not a new darkness creeping across the horizon. In the ’60s, the jazz community lost greats like Charlie Parker, Lee Morgan, and Dinah Washington. Rock and roll lost Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, and Janis Joplin. Punk rock lost countless heroes. Nineties stars Kurt Cobain and Bradley Nowell both fought uphill battles with addiction. “How could this happen?” is not a fruitful question. How we stop it from continuing to happen is.

It’s hard to look at tragedy at scale, to pull the camera back and think about overarching themes when the themes are death and destruction. The urge to quickly identify and chastise a scapegoat looms large. But nothing is solved by flattening multifaceted problems into one-dimensional vectors of causality. People are dying because there is pain in the world and not enough knowledge about mental health or tolerance or toxicology. People are going to jail because they lack opportunities and guidance. Treating the symptoms of disorder as the root causes is like prescribing cough medicine for a lung infection. It feels nice to get proactive, but it doesn’t curtail the issues animating troubling behaviors, the consequences they give rise to, or the stresses of seeing someone lose their freedom or their life. Regardless of who all is ultimately at fault, what we have on our hands is yet another generation that’s hurting. The blame game won’t fix that. Neither will tough love. You can’t just guilt-trip people off drugs or argue someone out of a life of crime.

When your musical heroes are cut off from their true potential, through death or other means, the grief subsides with time, but the wondering never leaves. It lingers in your mind forever, what they could’ve done with more opportunities to explore life’s mysteries, what they might make of a certain piece of art, how they might process certain news. People raised on ’80s and ’90s rap who admit to being puzzled by the motivations of new rappers know this feeling. Between 1996 and 2006, we lost 2Pac, Biggie, Eazy-E, Big L, Aaliyah, Soulja Slim, Big Pun, Jam Master Jay, O.D.B., J Dilla, Left Eye, Proof, and so many more to illnesses, accidents, shootings, and other horrors. We watched Slick Rick, Lil Kim, C-Murder, Beanie Sigel, DMX, and Shyne do time. We held out hope for Snoop as he fought for his freedom during the lengthy ’90s murder trial he ultimately beat. We didn’t, in the middle of all that carnage, clasp our hands and lament a fallen generation, or point to who taught them how to hustle, or how they got themselves into whatever mire they ended up in. We supported them, and we supported each other through it.

We should pay that energy forward as history repeats, while promoting practices that lighten everyone’s load. We should ask record labels to do more to coach artists on how to weather rapid changes in their living circumstances and press for a deeper understanding of the emotional and psychological weight that leads to drug use, and not just the fallout from artists getting too far into it. (This also goes for fans. Too many people seem to think depression and anxiety are fads, popular personality quirks people will ditch when they get bored.) If rap’s your business, then rappers are your responsibility. They’re not just quick investments, good to tap when their names are hot but not so much when they start spiraling out. What’s going on here is deeper than artists and personal responsibility, as much as the onus is also on artists to be responsible and take care of themselves and their camps. I wish I pieced that together when I wrote about how this era spooked me back in 2017. The judgmental distance in the way we talk about them, the misguided idea that something is happening here that has never happened in music before, is all noise. Until we cut through it, until we’re honest and loving and understanding, we’ll only keep talking in circles.