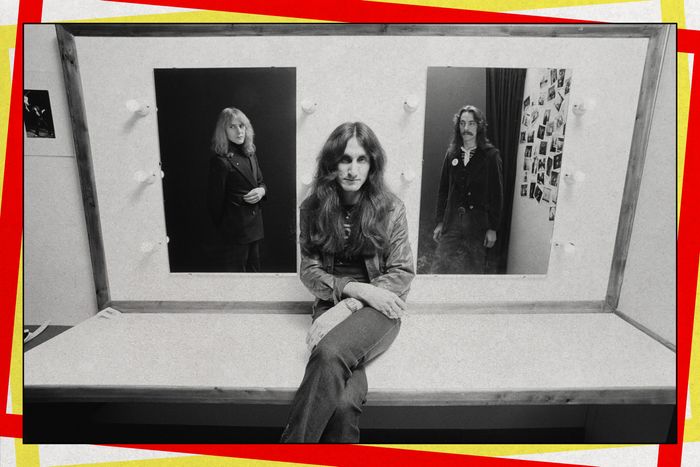

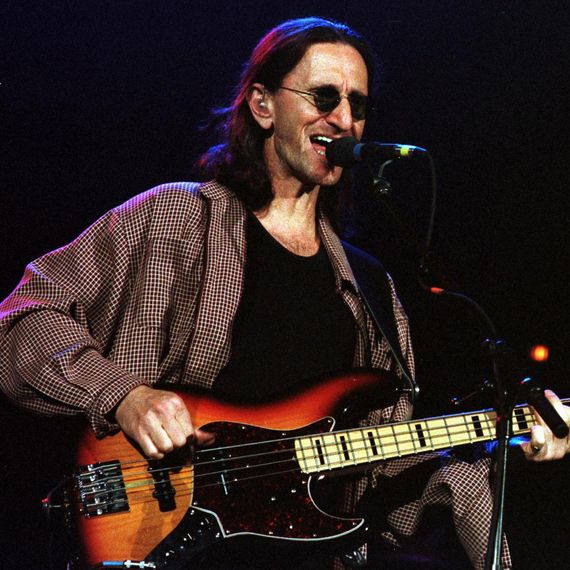

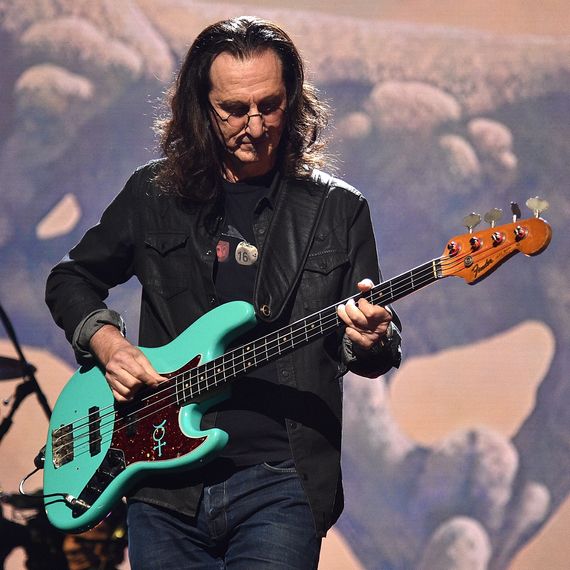

The main takeaway from Geddy Lee’s new memoir, My Effin’ Life, is that anything can happen as long as you live your life with an honest conviction. Rush took that idea one step further. Their music was rooted in interconnection, reciprocity, empathy, and an expression of friendship, all while somehow maintaining the image of a holy triumvirate of nice guys who you’d happily grab a beer and poutine with if given the chance. Low-key — they’re goofy dudes! Do we need to remind you of the laundry and rotisserie chickens? “It’s really comforting and reassuring to know,” Lee tells me, “that our music achieved some sort of universality in terms of its audience.” As Rush’s bassist and lead vocalist, Lee was the interpreter of drummer Neil Peart’s lyrics and stabilizer of Alex Lifeson’s guitar shreds, all while serving as the band’s invariable eye of precision in the studio. And yes, he really knew how to slap that bass.

Following Peart’s death in 2020 from brain cancer, Lee and Lifeson confirmed the band as we know it is over. The duo have suggested, though, that they could one day record new music together if the inspiration strikes. But until that day comes, at least we have 19 albums worth of progressive opuses to enjoy. “We were cursed or blessed,” Lee says with a laugh, “with an insatiable curiosity about where we could push our music to.”

Song that legitimized your ambitions

With a career as long as ours was, fortunately, you find yourself in that kind of situation more than once. I would say the first time I felt our aspirations had been somewhat legitimized was after we released 2112 and we had been looking for a sound to call our own. We had been trying to carve out this balance between a conceptual band and a rock band — sort of unsuccessfully as a whole — but there were moments on the early records that pointed that way. 2112 was the first time all those things came together after the smoke had cleared. We really didn’t believe our careers would go very far because of the failure of Caress of Steel. No one was more surprised than us after 2112 was so well-received by fans more than the radio, for example. It became, “Oh, wow, this is kind of where we wanted to go and we pulled it off.”

We were a band that didn’t really ever know how to stay in one place. Improvement doesn’t happen in a straight line. You have to take some chances and you have to be prepared to fail in public to get to someplace better, so sometimes that took us on a sideways journey. I would say Permanent Waves was another moment we had set out to begin to make our music as adventurous but in a more concise way. Trying to accomplish in five or seven minutes what we wanted to do in ten or more minutes — songs like “Natural Science” or “The Spirit of Radio.” That idea continued into Moving Pictures. You could say Moving Pictures was more satisfying from that perspective, but I think Permanent Waves was a turning point.

Song that will always remind you of Neil

“The Garden” from Clockwork Angels. It’s because of the nature and almost foreboding atmosphere of that song in terms of what eventually happened with my friend and bandmate. The statement of that song talked so much about where he had found himself in life. Many times I’ve thought about … well, it’s hard for me to listen to “The Garden” without thinking about him unknowingly at the end of his life.

I remember Alex and I had been throwing some ideas around in my home studio here in Toronto. He had gone for the day and I came into the studio the next morning, listened back to some of these little ideas, and started playing on my bass. “The Garden” just came out. I put together the intro with a little bit of a synthesizer part and it moved so beautifully into the verses. Alex came in the next day and it also made perfect sense to him. The song very quickly gelled based on these different stanzas of lyrics we had in front of us. It was really beautiful to write. It wasn’t torture. Some songs are torture, right? You sweat over it and you tear your hair up. The whole experience of making “The Garden” from the beginning through the end was a real joy for us.

Song that should be adapted into a screenplay

There are a couple that could make very different types of films if someone wanted to take them on. 2112 is obvious as a sci-fi story of “the individual against the collective.” I think the setting of it would lend itself to visual interpretation. Whether that’s been done too much, I don’t know. You’ve got generations of Star Wars films. It’s not new territory, but there’s something in that story that would translate into the genre. But more importantly and more originally, I’d love an interpretation of the entirety of Clockwork Angels. It’s based on a classic story of a naïve and innocent person going out into the world, and running away to try to find the place to make his dreams come true. He goes through all those various phases of his life where he’s duped, where he recovers from that, where he falls in love, where he loses his love, and then it all adds up to the fullness of his life. That really would lend itself to a fantasy story, but not necessarily a sci-fi fantasy story. When you look at what’s been done with shows like The Last of Us or Game of Thrones, you can take cinema anywhere now. Yet the story at the heart of Clockwork Angels is a full circle of life.

I’ve received ideas for 2112 on and off for many years, but nothing has ever really made us want to go down that road. I know Neil always wanted to bring the Clockwork Angels story to the screen in some way or another. It was a big deal for him, and he had done some work in the hopes he could make something like that happen. Maybe one day.

Most epic song

We did tend to go on a bit. If you think about “La Villa Strangiato,” which is an instrumental song, we kind of threw everything but the kitchen sink into it. In a strange way, even though that’s one of the longest songs we’ve ever put together, it was instructive. By the end of it, we had created a bit of a template for how to approach future instrumental songs — and there were quite a few in our career following “La Villa Strangiato.” Most of them were more concise, but nonetheless, that was the beginning of our whole obsession with fine-tuning the instrumental songs.

At first, a lot of our instrumental factions were indulgences. This song was the indulgence of all indulgences. It was an exercise in self-indulgence. But when you’re doing a song that has lyrics and a lyrical theme you have to adhere to, there’s a very strict script you have to stick to. But with an instrumental song, you can do whatever you want, you can go wherever you want, you can indulge any mood, and you can make it all about mood. “La Villa Strangiato” is a song that has quite a few moods. That was something we learned we could take forward and use our playing abilities whenever we felt, “Okay, we’ve got all these ideas, but none of the lyrics really suit it, so why don’t we just establish a mood and then go off down that road?” I was really pleased with that. It’s a nice thing to do and always felt like a reward after slaving to get the right feel and right melody to serve a piece of lyric. Not having a lyric was like a holiday.

Song that best represents your own value system

I would say “Dreamline” and “Bravado,” which follow each other on Roll the Bones. Those are two of my favorite lyrics Neil ever wrote, and they were beautiful to sing because I could identify with them so very much. The sentiment of “Dreamline” is that we’re only immortal for a limited time. I really identify with how important it is for me as a human being to try everything — to run around the world at breakneck speed, try to see what there is to see, and feel what there is to feel. My curiosity and appetite for life is huge. When you’re young, you don’t think anything’s going to stop you. As you get older and experience more of life, you realize how lucky you are to have that feeling for as long as you can, because life changes that.

“Bravado” fits in because of the nature of knowing and learning what the cost is. There’s a difference between being willing to pay the price and counting the cost of that. The things you do and the actions you take have a price. Every time you win or go out in the world and think you’ve climbed that mountain, maybe you then realize there was a cost you have to pay in some way or another. Those two songs go hand in hand with my life’s view.

Favorite spontaneous studio track

“The Twilight Zone” was the first time we attempted something like that. We had five more minutes worth of vinyl we could’ve used and didn’t have a song. We’d been slaving over every detail of side one of 2112. So we put the song together very quickly — our little ode to Rod Sterling, the creator of that show. When I hear it today, it’s still really satisfying. I really like that song, even if it’s one of the lesser songs in the Rush catalogue. It sparked an idea that we came back to. “Vital Signs” and “New World Man” were other examples of those types of songs. But “The Twilight Zone” remained my favorite moment of spontaneity.

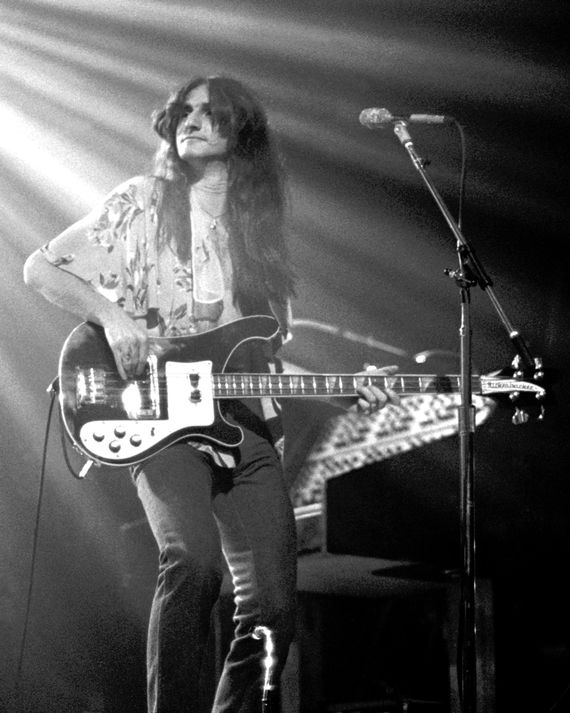

Song where you achieved your sound and style as a bassist

“Red Barchetta” was the quintessential Ricky sound for me. I was really happy with the song’s sound because it’s quite an expressive bass part and a dreamy story, but the bass cuts and punches through with that nice balance of the bottom end and crunchy top that’s so hard to always make work. “Red Barchetta” for me was an establishment of that tone.

My job as a bassist in a trio was to somehow create a tone that had enough bottom end to be satisfying. A bass player is supposed to provide the bottom end — it makes you rumble and makes you move. I had to make sure I had enough of that going on. At the same time, I’m a kind of obnoxious player. I want to be heard. I don’t want to just be satisfied with tickling the bottom of people who are listening. I’m happy to tickle your bottom, but I want to crunch at the top. I want to make a statement. It led to a lot of experimenting. The trick in Rush was always to be able to find a proud sound for the bass that still worked with the other instruments and didn’t hog too much of the spotlight. We tried to share the spotlight. To be aggressive and stay out of the way when you needed to stay out of the way was always a challenge for me.

Song where you found your voice

I think my voice had periods like the music of the band. In the early period of my singing, I was kind of a shout-singer where I was quite heavily influenced by Steve Marriott from Humble Pie. We both came out of a bluesy background of music. My voice had to cut through and a lot of times there was less melody and more power and a histrionic sort of delivery — something that didn’t endear me to many critics, but one that worked very well for the style of music. As time went on and our songs expanded in their potential, I had to actually learn how to sing and to use my voice in various ways. “The Analog Kid” was one of those songs where the choruses first allowed me to sing out in a more plaintive and melodic way. I followed that up with “Mission” on Hold Your Fire. Those two songs show the growth of me as a guy going from being a screamer to a more melodic vocalist. I had an abrasive, raspy soprano that over time was tamed and pushed into a more melodic context.

Bassline you obsessed the most over creating

Because of the nature of the way we write, most of the important basslines were already worked out by the time we went into the studio to record. So the struggle happens during the writing session and then you have to get that performance. Certainly parts of “La Villa Strangiato” were difficult. The middle section of the song “Mission,” where Neil and I go off into this jazz tangent, was something that required a lot of focus and skill to make sure we could nail it together live. Mostly the instrumental bits are the ones that are challenging.

When you listen to the bass part in the chorus on “The Anarchist” from Clockwork Angels, it’s one of my favorite bass parts I’ve ever written. But when it came to being able to play and sing it live, it was almost impossible. I have to split my brain into such completely independent things because the vocal melody and the syntax have no relation to where the bass is going. That was one of the great challenges I’ve ever had — learning that song to be able to play it live. I loved writing it because it’s one of those songs where I double-tracked my bass with an octave above, so there’s really two basses playing in sync with each other, one an octave higher than the other. It gave it this really broad soundscape that moves that chorus.

When I was a kid and listening to the radio before I was a bass player, I was absorbing all these Motown songs, because that’s what was on the radio a lot. I was subconsciously channeling James Jamerson’s beautiful basslines. I’ve always admired how it’s the bass in Motown songs that really move the song along. Even a song like “My Girl,” which you think has nothing to do with Rush. Why is Geddy Lee talking about “My Girl”? Listen to that bass part, man. James Jamerson knew how to take a part of a song and make it move in a beautiful way. The chorus of “The Anarchist” is that kind of bass part and my subtle tribute to him.

Album with the most issues to overcome

Vapor Trails was a very, very difficult record to make, because it was sort of a reunion record after Neil’s tragedies in 1997. He disappeared from view for quite some time and found himself living in California and starting a new life. He came back to us, as he put it, “seeking gainful employment.” The whole idea of making Vapor Trails had to be very considerate. We settled into a studio for almost a year and constructed a working environment so Neil could feel free to go in and reintroduce himself to his drums and his playing without feeling like everyone’s watching him. Alex and I worked in another part of the studio where we could just get on with it, but it had been so long since we’d written together that the ideas were coming slowly, and the early ones weren’t satisfying. We had to push ourselves and discard the bad ideas. We got kind of paranoid when we finally had a great idea, because we wanted to grab it on tape and keep it. We were nervous that we wouldn’t be able to reproduce it if we started rerecording everything from scratch.

There was so much emotional static and fear that the whole process became very long and imbued with paranoia. By the time we had assembled all these songs, which we were very happy with, they were coming from a whole variety of sources. Some of them were jam sessions that we kept on tape and never fine-tuned sonically. Right through the project, by the time we got to the mixing process at the end, it was problematic. It was difficult because a lot of the sounds on this very dense record weren’t recorded in an ideal way. It became an impossible journey to get the record made and get it sounding the way we wanted to. We exhausted our original engineer and co-producer, and had to bring somebody else in to help us finish it. It was just a fucker to make. A real fucker.

Album you’ve begun to interpret differently through the years

When I look back at some of the earliest material around Fly by Night and even parts of 2112, I’m shocked at how fast we’re playing. Like, “Where’s the fire, guys?” I always knew and appreciated that we were hyperactive, especially as a rhythm section. Neil and I got off on being that way, but I wish now in retrospect we would’ve slowed down just a wee bit and allowed the songs to groove and breathe a little bit more. That’s something I interpret differently than I did when we first made those records, because I didn’t hear it at all that way back then.

A few songs may have also been a little naive in their original intent. The nasty little tale called “The Trees,” of course — a comment on forced equality. Being a much more liberal-minded adult, I now have a softer approach to things in life and I’m much more open and willing. I put a lot more importance on social responsibility now than I ever did. I talk about that, of course, when I’m referring to free will. There were a few things we sang about in our early twenties that seemed very important. But as time has gone on, you ameliorate those views because life has told you it’s not so simple. Once you encounter problems and you begin to help your family or friends with some of those problems, you learn a lot about how much of life has lived in the gray areas as opposed to the black and white areas.

Laziest misconceptions you’ve encountered about Rush

Oh God, there are so many.

There was a time where the religious-rights were trying to stomp out progressive and metal bands of our ilk. I remember we were excoriated by one newspaper for being “devil worshipers,” which is just the most ridiculous thing I ever heard. Neil wrote a rebuttal that actually got published in the same newspaper, which I thought, Bravo for him. There was also a big free-for-all made by New Musical Express, who thought we were fascists and 2112 was a fascist piece of music. It was a completely absurd interpretation. That was, to me, so stark and bloody wrong-headed and subjective to that particular writer’s view of the world.

We were music written by players. That was our essence. Players’ music tends to be technical and appeal to other aspiring players — and in the 1970s, far and away, there were more men in that category than women. But there’s been a revolution in terms of gender. I think we had so many young boys at our shows because that was the bulk of what the musicians were back then, and that’s changed and evolved. I think as our lyrics became more philosophical, more worldly, and dealt with more issues, it appealed to a kind of mentality that went beyond the young-boys musician crowd. The narrowness of our fan base started to expand with more universal lyrics. As we got older, I would look into the audience and there were moms, dads, and children of all genders.

How your Colbert Report and I Love You, Man appearances altered the band’s reputation

We had just endured a very heavy number of years. When it came time to go forward into the world and actually do a tour, we were more relaxed because we had been given a new lease on life. We had a second chance to be a band and didn’t want to repeat the obstinate, out-of-hand decisions we made in the past. For instance, we never wanted to do television shows. We always thought, That’s a hassle, bands never sound good, blah, blah, blah. So we started to take what I consider “the Costanza method,” based on that Seinfeld line where Jerry says to George, “If every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right.” If somebody came up and said to me, “I have a movie pitch. Do you guys want to be in this comedy film with Paul Rudd and Jason Segel?” I would now say, “Yeah, sure, we’ll do it.” The same thing for The Colbert Report. We’re fans of Stephen Colbert and we knew it was a comedy, so why not? A lot of these people were Rush fans when they were younger and somehow felt an obligation to pay it back. That means a lot. It really does mean a lot.

Saying yes to things we normally would’ve dismissed made us happier as a result. We were doing fun things and everything seemed like a new adventure. It didn’t feel like we were repeating the program of Rush 1.0. We started behaving out of our previous characters. We were looser on stage — our onstage persona became much more fun. We started adding humor to every aspect of what we did. We would try to squeeze something funny in so that fans could come to the show, hear those same songs and listen to those long instrumental sections, but maybe somewhere along the way there would be a joke to also put a smile on their faces. I love when a Rush audience is smiling and laughing. That was the motivation.

More From The Superlative Series

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music

- Cyndi Lauper on the Freest and Most Provocative Music of Her Career