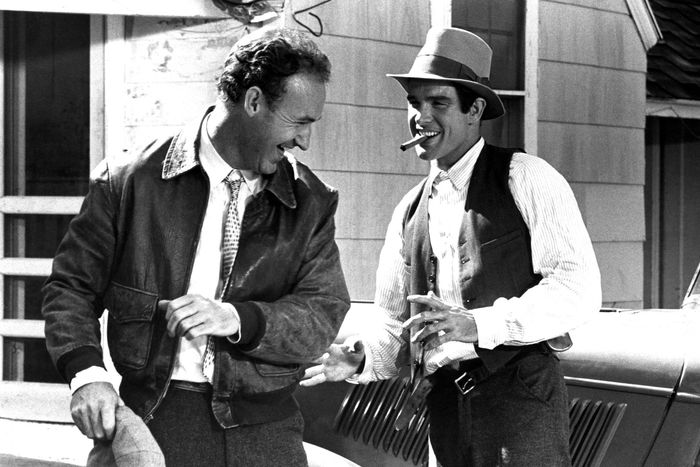

Gene Hackman was a virtuoso of the smile. When the corners of his mouth curled up, this split-second pause before the unveiling told you something thrilling was about to happen, but he was so inventive that you never knew quite what. It made Hackman, who died at 95 with his 65-year-old wife, the classical pianist Betsy Arakawa (in what authorities are currently saying was probably not foul play but clearly requires some investigation), one of the biggest stars of the 1970s, and guaranteed him full employment until his retirement some 20 years ago.

If Hackman flashed his teeth in delight, there was a chance his character might suddenly punch or shoot someone a moment later. If there was a wink and a “heh heh,” the odds rose: See the 1995 Western The Quick and the Dead, a film packed with insinuating smiles, especially the scene where Hackman’s despot sheriff, John Herod, warns Sharon Stone’s vengeful gunfighter to leave town, fixes her with a lipless sneer, casts a glance toward a henchman (signaling that he should be ready to shoot), then slaps her and restrains her from striking back, smirking in presumptive triumph. If the Hackman smile stayed fixed for more than a couple of seconds and his eyes lit up with joy, protracted cruelty might be incoming. Think of the scene in The French Connection where his brutal racist narcotics detective, Popeye Doyle, repeatedly asks a regular in a Harlem bar, “Ever pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?” It was an interrogation tactic to disorient suspects by hammering them with nonsense.

Other times, the Hackman smile masked confusion, treachery, cowardice, or brokenness. The 1974 Francis Ford Coppola thriller The Conversation, in which Hackman plays a surveillance expert named Harry Caul who gets pulled into a conspiracy, incorporates dozens of subtly different but equally intriguing Hackman smiles, several of which are piled into a sequence where Caul hosts an impromptu party at his shabby office. In the space of a couple minutes, we get a cocky “yes — the legend is true” smile as Caul’s partner (John Cazale) asks him to tell the story of the time he “hid a bug in a parakeet,” followed by an alpha-dog grin as Caul shows off a handcrafted shotgun microphone, a “who’s the nerd now?” smile as he draws a prospective one-night stand into an embrace; a gratingly overdone chuckle as he deflects a colleague’s proposal for a partnership by telling a homophobic joke that gets a blank look; and, as he walks away, an “I sure landed that joke!” smile that amounts to a silent laugh track.

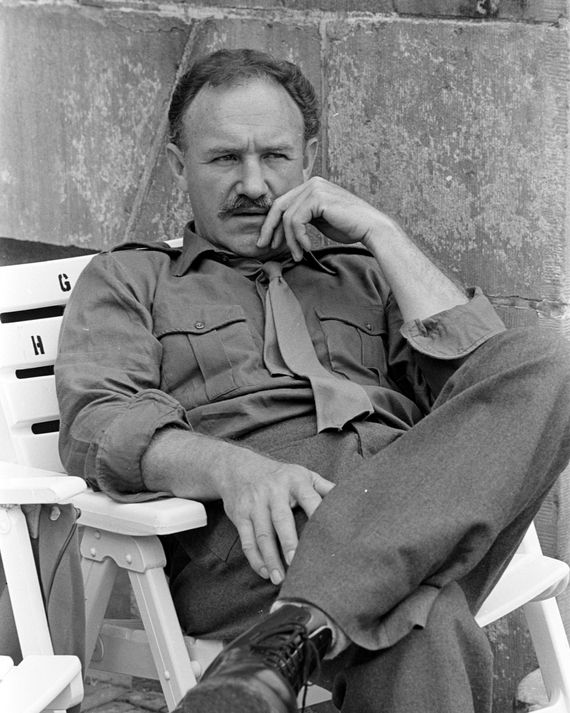

Even during a decade in which Shelley Duvall, Richard Pryor, Dustin Hoffman, Liza Minnelli, Telly Savalas, and other performers with faces off a city bus became marquee names, Hackman stood out by appearing ordinary while setting up bespoke fireworks displays. He was middle class; educated and imaginative, but not self-consciously artsy; a westerner with a drawl-adjacent vocal manner that could convey anything from the neon citadels of Los Angeles and Miami to the plains of Kansas and Iowa.

Hackman was born in California and raised in Danville, Illinois, disillusioned by his parents’ divorce and his father’s abandonment of the family, seasoned by time in the U.S. Marine Corps (he lied about his age to enlist at 16) and acting classes in Pasadena and New York (where he roomed with both Dustin Hoffman and Robert Duvall). Over his four decades of work, he became a patron saint of American dads — a fantasy identification figure for men who did not live anything resembling dangerous lives but still felt pretty sure they could take out a home invader if it came to that. His persona was a paragon of the hale straight American white guy spotted in droves from Puget Sound to Indianapolis and on down into the panhandle of Florida, with a wife, two grown kids, and two mortgages, probably a Republican but open to persuasion. He was one of those men who looked about 50 whether he was 30 or 70. He had broad shoulders, meaty hands, narrow eyes, a borderline–W.C. Fields nose, and a paunch modest enough to hide in a windbreaker. His hairline was already receding when he started acting, and when he disguised that it was often for comic effect, as when he played the old blind man who unknowingly torments Peter Boyle’s monster in Young Frankenstein and Lex Luthor opposite Christopher Reeve’s Superman. (Luthor was bald in the comics, but Hackman told director Richard Donner he didn’t want to go through the hassle of maintaining the look — a diva demand that paid off marvelously at the end of Superman: The Movie. (As the hero delivers him to prison, Luthor defiantly yanks off a wig we didn’t know was a wig and announces himself to the warden as “Lex Luthor … the most brilliant criminal mind of our time!”)

Talent and energy fueled Hackman’s long and varied career, which teamed him with some of the greatest directors, writers, and actors ever. He got a Best Actor Oscar for The French Connection and a Best Supporting Actor for playing the sadistic small-town sheriff Little Bill Daggett in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, who beats Eastwood’s alcoholic gunfighter within an inch of his life before dying of lead poisoning. Hackman got three additional nominations from the academy, for playing Clyde’s brother in Bonnie and Clyde, who gets dragged into the lovers’ bloody rampage; the hero of I Never Sang for My Father, who’s guilt-ridden over his decision to move cross-country and abandon his aging pop; and Mississippi Burning, as an FBI agent named Rupert Anderson who uses his bona fides as a good ol’ boy to crack open a case against Klansmen who murdered civil-rights workers. The latter film was controversial because in the real-world 1960s, the FBI was more likely to surveil, harass, and frame civil-rights activists than avenge them. But Hackman’s character was based on a real agent who was instrumental in solving the killings, and his live-wire performance blunted the fact-checkers, turning Anderson into a progressive fantasy echo of Popeye Doyle who cherry-picked his biography to charm and smash the racists. Along the way, there were trophies and citations from everyone else imaginable. The Golden Globes awarded him Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy for The Royal Tenenbaums, a production in which the mercurial Hackman clashed with his young director, Wes Anderson, who later called him “one of the most challenging and best actors I ever worked with.”

All in all, Hackman’s career makes a case against the received wisdom that physically transformative “chameleonic” acting should be considered the pinnacle of the trade. Hackman rarely changed his appearance beyond adding or subtracting glasses or facial hair. But he was never the same guy twice — not even in the 1998 techno-thriller Enemy of the State, a project in which every key creative player, including director Tony Scott, insisted Hackman was reprising The Conversation’s Harry Caul even as Hackman was busy playing somebody new (for him): a black-ops answer to Sean Connery’s Untouchables cop, tutoring Will Smith’s fugitive in the art of hiding and seeking. The Gene Hackman who played the self-sacrificing priest in The Poseidon Adventure was physically indistinguishable from the ex-athlete turned private eye in Night Moves; the inspirational coaches in Downhill Racer, Hoosiers, and The Replacements; the tyrannical submarine captain in Crimson Tide; the aforementioned Herod in The Quick and the Dead, who denies fathering the teenage son who wants to kill him in a gunfight; the straying husband and steelworker in the little-seen but engrossing marital drama Twice in a Lifetime, from 1985; and the pathetic producer in Get Shorty who recycles cool-guy lines spoken by the movie’s badass loan-shark hero with the same success rate as Harry Caul telling jokes.

Hackman was especially adept at dramatizing the abuse of power by men who thought they could get away with anything but found that assumption tested by their own hubristic blunders. In No Way Out, Hackman plays Secretary of Defense David Brice, a professional glad-hander and power-tripper who flies into a rage when he suspects his mistress (Sean Young) is seeing another man (Kevin Costner), accidentally kills her during an argument, and subcontracts the cover-up to his right-hand man (Will Patton), a sociopath who worships Brice. Hackman is extraordinary, and absolutely ego-free, in his performance as a man whose guts are all in his job title; once Brice commits a capital crime that he mentally redefines as a careless mistake, he goes from swaggering power broker to cowering whiner so fast that you’d think a switch had been flipped.

In The Birdcage — a remake of the 1978 French farce La Cage aux Folles, adapted by Elaine May and directed by Mike Nichols — Hackman plays another powerful Washington insider, an opportunistic Republican senator and vice-president of the Society for Moral Order named Kevin Keeley. While pandering his way through a hotly contested election, the senator ends up getting bamboozled by his own daughter and future son-in-law, who convince one half of the groom’s same-sex parental unit to don drag and pretend to be a mom so that Senator and Mrs. Keely will approve the nuptials. It’s Hackman’s sharpest comedic performance since Lex Luthor in the Superman series: an unpeeling onion of naïveté. It’s inevitable and comically correct that Keeley would end up in Barbara Bush finery as he sneaks through the hero’s rainbow-coalition-coded Miami nightclub to escape reporters, but what puts the sight gag over the top is Hackman’s intricate portrayal of a man who is shocked to find himself open to previously unthinkable experiences. “No one will dance with me,” says the senator, with a faraway look. “I think it’s this dress. I told them white would make me look fat.”

A year after The Birdcage, Hackman played the president of the United States in the Clint Eastwood thriller Absolute Power, about an aging cat burglar who happens to rob a billionaire’s mansion on the night when the chief executive is trying to bed the billionaire’s young wife. The president is a monstrously selfish and overbearing misogynist who tries to overpower his date after she resists his violent advances. The Secret Service settles things in his favor, with bullets; Hackman’s reaction as the smoke clears is even more chilling than what we’ve seen in prior performances as important but craven men. The character combines the entitlement of Brice in No Way Out and the alienation from normal human behavior that becomes a comic spectacle in The Birdcage with a level of darkness that wouldn’t be out of place in a David Lynch production about evil forces possessing mortals. He’s revolting and terrifying — and he looks more or less exactly the same as the other two Washingtonians. It seems astonishing that a man who rarely changed shape could shape-shift with such assurance until you remember that the essence of acting is pretending. If you’re engaging enough to get the audience on your side no matter what — as Hackman was — all you need to do to suspend disbelief is walk onstage and say, “Here I am on a surfboard in the ocean” and wait for onlookers to imagine the crashing waves.

That triptych of roles in politically adjacent genre movies — No Way Out, The Birdcage, and Absolute Power — is also a vivid illustration of what we might call the Gene Hackman Principle of Transformative Acting: The best special makeup is talent. He’s visually the same guy in all three movies, down to the suits and ties, but if you watch them in a row without knowing the plots going in, you could never guess what Hackman’s character was going to do based on what you’d seen last time. Each new assignment was a chance to revisit the familiar and make it feel brand new. The patriarch Royal Tenenbaum summed up that brand of creative chaos in the “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard” montage, where he resolves to show his sheltered grandsons how not to play it safe, dropping g’s by the handful: “I’m not talkin’ about dance lessons! I’m talkin’ about puttin’ a brick through the other guy’s windshield. I’m talking about takin’ it out and choppin’ it up!”

Hackman seemed to know himself. He didn’t give many interviews, but when he did, he was upfront about how much of his success came from relentlessness — the same type he often showcased in his movie roles. He told Vanity Fair that his actor origin story was overhearing a former fellow Marine who had attended one of his early stage performances mocking Hackman’s brief performance as a bellhop. “I wasn’t going to let those fuckers get me down,” he said. “I insisted to myself that I would continue to do whatever it took to get a job. It was like me against them — and in some way, unfortunately, I still feel that way. But I think if you’re really interested in acting, there is a part of you that relishes the struggle.”

He certainly relished it — and even more so, the cathartic experience of mastering the lines, the scenes, the role, the craft. Hackman was at home in every budget level, style, genre, and decade of his acting life. He was a sledgehammer talent, shattering any complacency that filmmakers and fellow actors might’ve brought into a project. But he was also a handyman — the kind of reliable, all-purpose day player who could fix casting and storytelling problems by showing up and raise brief moments to iconic status (as in another Nichols comedy, Postcards From the Edge, in which he plays the most empathetic, measured, polite, loyal Hollywood blockbuster director in all of movie history, with such grace that he fools you into thinking such a man could exist).

Hackman withdrew from acting a few different times once he got past 70, finally bowing out for good after the 2003 comedy Welcome to Mooseport. By the time his own story ended, he had nothing left to prove, even as a multi-talent (he carved out a second career writing and co-writing well-regarded western and adventure novels featuring strong, simple good guys; nasty bad guys; and resourceful mothers and children). His final exit, after years of distance from the public eye, was uncharacteristically mysterious.

It’s probably inevitable in a final analysis like this that we think back on the death scenes in an actor’s repertoire. Hackman had so many great ones that his short list would not be short at all. Among the highlights are the priest’s immolation in The Poseidon Adventure (going silent and letting onlookers absorb the profundity of his sacrifice before dropping into a pool of flame); Herod’s death by gunfire in The Quick and the Dead (he’s so astonished to have been shot in the chest that he gives the heroine time to finish him with a shot through the eye); and Bill Daggett’s wheezing, glassy-eyed sign-off in Unforgiven (“I don’t deserve to die this way; I was building a house!”). Alive even in death: That was Hackman. It’s enough to put a smile on your face.