Hans Zimmer’s scores cannot be contained by even the biggest movie screens. They demand live audiences crying to The Lion King in 20,000-seat arenas and sloshed Coachella-goers swaying to the Pirates of the Caribbean strings after dusk. You’ve heard “BRAAAM,” or something like it, in umpteen trailers, but you haven’t really heard it until a stranger in the next row starts pointing at the stage like Leonardo DiCaprio in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Few people who aren’t pop stars can pull off the type of tours Zimmer has been doing for the past several years. In addition to being a current Oscar contender for Blitz, the veteran composer is now playing shows across the United States and Europe with dates scheduled through March 2026. Onstage, Zimmer condenses his 43-year career into a sprawling showcase that spans the many genres he has worked in. You might hear Driving Miss Daisy next to Pearl Harbor and The Prince of Egypt before Inception. Over two to three hours, the largely self-taught German multi-instrumentalist, who parlayed his work with late-’70s New Wave bands into an iconoclastic Hollywood legacy, shows off the uncommon melodic structures and innovative methods that have given his work such a foothold in pop culture.

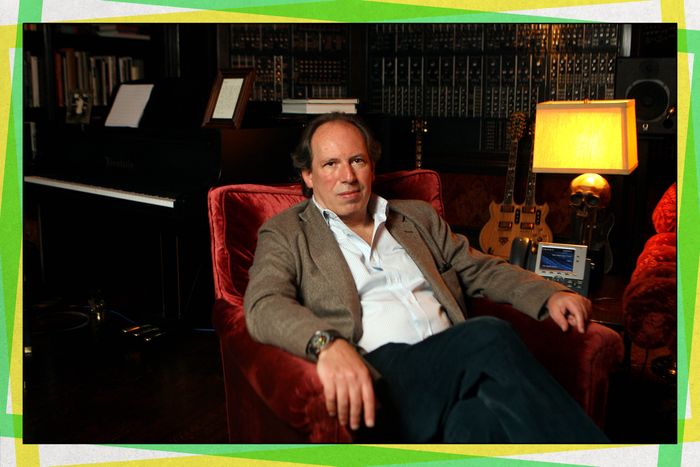

Right before Christmas, Zimmer appraised his career from the comforts of his opulent Santa Monica studio. “I’ve done romantic comedies, I’ve done war movies, I’ve done race-car movies, I’ve done thrillers and absurdity and pirates,” he said. “I mean, there’s very little left.”

Most technically innovative score

Inception because I managed to go and fuck with the very fabric of time. There’s a point where three things are going on. It’s like trains crossing, all at different tempos, but then they all meet and they’re all harmonizing with one another and then float away into their own little worlds again. Interstellar is also interesting because we used a pipe organ. Nobody other than a horror film has used a pipe organ.

Weirdest place you’ve heard “BRAAAM” used

I try not to hear it. After everybody used it in their trailers, it sort of cheapened our use in Inception. Chris wrote in his script about hearing over the city the sound of horns being slowed down, so I took the third trombone note in the Édith Piaf song “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien,” slowed it down, and did a few other naughty things to it. I had all these brass players in London in this beautiful hall. I had an open piano, and I put a brick on the sustain pedal. They played into that, so the whole piano was resonating. It was a story point and then “BRAAAM” became every trailer’s favorite device for how to get from one non sequitur to another. It misquoted the language.

Score that inspired the most copycats

I thought I did something quite original on Rain Man, and by the end of the year, there were a thousand Rain Mans around. Rain Man is a road movie, and road movies are usually either jangly guitars or lush strings, right? So I didn’t do lush strings or jangly guitars — or jangly strings or lush guitars. I had weird Cuban rhythms, I had synthesizers, I had fake panpipes. I kept thinking, This should be music from Mars. There’s actually a scene where they drive across a bridge, and the bridge resonates in a certain key, and the music is written in that key. And that music was sent to Dustin Hoffman in New York so he could go and hum in the right key. There were real ideas behind it. It’s the German word Gesamtkunstwerk — we made one piece of art, basically.

Biggest crowd-pleaser during your live shows

It’s probably the end of the show, going from Lion King into James Bond. Or the way we end the first act with a 14-minute version of Pirates. I’m not short of good material. The thing that seems to move people the most is a very long version of Interstellar. It holds up, which is good.

The one rule I gave myself for these shows was I will never use an image from the actual movie. They’re going to be distracted. I give them the purest version I possibly can. What I do is watch the audience and see what resonates. When we did Coachella, that’s really where Lion King became a topic of discussion because I said, “Oh, no, we’re not going to do a kids’ movie at Coachella.” Nile Marr instantly said to me, “Hans, get over yourself. That’s the music of my childhood.” So we did it. It was amazing because there were 80,000 people quietly weeping.

Most underrated score

The Fan. Nobody went to see the movie, and the score is unflinchingly dissonant. There’s a nihilistic poem that I read through a vocoder and you cannot understand the words, but it’s really evil. Don’t-try-this-at-home type of music. But I sort of love it, and I suppose I’m just going to ruin the next tour because the whole band is basically going, We’ve got to put this into the next show. I don’t think an audience is interested in playing it safe. They want to have an experience. They want to be right at the edge of disaster. And that’s where I live.

Score you’d like another shot at

I’ve done a lot of movies that failed, The Fan being one example. I can get into that mode where everything I’ve ever done is terrible, or not terrible, but I haven’t actually written the piece that I feel I’m capable of doing. I remember I played something for Gore Verbinski, and he said, “Yeah, that’s good if you want serviceable and ordinary.” That was on Rango. Serviceable and ordinary went out of the window at that moment, and it became something completely different and impossible to do. People nearly died on it. You’d have to listen to it because it’s very hard to describe psychedelic country-western rock and roll with a heavy disco beat.

Franchise you wish you could score

There’s never enough pornography.

No, there’s very little left for me to score. I remember working on a film, and the scene was Paris by night. It’s raining, and a girl has just broken up with her boyfriend, and she’s walking along the Champs-Élysées and she’s crying. The director is starting to explain the scene to me, and he’s a friend, but he spends a long time explaining the scene, and I finally have to say to him, “Do you know how often I’ve written this scene already?”

Biggest cultural contribution other than “BRAAAM”

Taking this music and successfully touring it in arenas and being sold out everywhere. Other than John Williams, I don’t think anybody else can really do that. And I’ll tell you why it’s culturally relevant. The reason I did it wasn’t just because I was bullied into it by Johnny Marr and Pharrell but because I was really afraid that orchestras were going to become redundant because people will say, “Oh, that’s not modern” or “That doesn’t mean anything.” I wanted to say, “Hey, look at this. This is really relevant stuff.” So it’s a constant desire to save the orchestras. There’s so many nasty and disgusting things you can say about Hollywood — and they’re all true — but you can’t take away the fact that Hollywood is maybe the last place on earth that commissions orchestral music on a daily basis. If we lose the orchestras, we lose a huge chunk of what makes us human.

Favorite Christopher Nolan collaboration

Interstellar, just because of how it started. Chris sent me a letter and said to write whatever came to me. He wouldn’t tell me what the movie was, but he wrote me this fable. It arrived on thick paper, and I know it was typed with his father’s typewriter. It was really about what it means to become a father, how you always look at yourself from then on through your children’s eyes. He knows my son Jake very well, so I thought that’s what he was writing about. So I basically wrote a love theme to my son. I finished around ten at night. I phoned Chris’s house, and his wife and producing partner, Emma, answered. She said, “Chris is pacing around. He’s really antsy. Do you mind if he comes down to hear it?” He came down and sat on my couch. I never look at somebody when I play him something for the first time. It’s too scary. I played him this small, fragile piece, and I said, “Well, what do you think?” He said, “I suppose I better make the movie now,” and I’m going, “What is the movie?” And he started to talk about space and ginormous journeys and the end of the world and all that stuff. I said, “Hey, hang on. Stop, stop. I wrote you this incredibly intimate, private, tiny piece.” He said, “Yeah, but I now know where the heart of the story is.” That was great. Then we just sat down and made a list of things we had done. “We’d done the big drums, so what have we got left in the repertoire of instruments?” And Chris actually said, “Have you ever tried using a pipe organ?” Nobody had added any new vocabulary or material to this amazing instrument. The piece I played for Chris is called “Day One,” and it appears all the time in the film.

Best Prince interaction

I met him a lot of times. I will not be able to quote the specifics, but he would say something really provocative, and I would be going, What the fuck? And two days later, I would go, Wow, he’s absolutely right. I felt the revolutionary spirit all the time. I liked him very much because he was gentle as well. That movie I’ll Do Anything we did was a disaster. You had all these fantastic Prince songs, but you have to warm an audience when you do a preview. You have to say to them, “You’re going to see a musical now. People might sing.” They just weren’t prepared for it, and that’s not what people wanted at the time. I have the most unbelievable demos with Prince — priceless, gorgeous, brilliant. Sometimes it’s just a drum beat and him on the piano. Other times, it’s really polished and finished, but it’s the rough ones I love.

Most unusual object you’ve incorporated into a piece of music

Dune is full of instruments that we designed and built, some of them electronic but some of them built by this wonderful musician Chas Smith. Unfortunately, he died while we were doing Dune: Part Two. His whole house was basically a resonating chamber, and he had some unholy alliance with Boeing and Lockheed where they would give him scrap metal. It was all things I’ve never heard of, and he would go and build these sculptures, basically. That’s why it had to be his house, because some of it was so big and so heavy that you couldn’t transport it anywhere. Dune is pretty much all modified instruments or built from scratch. We would record the music through these sculptures because I firmly believe that if you want to be true to science fiction and world-building, you need to not go with a middle-of-Europe orchestra. I love orchestras, but using an orchestra says that, in 10,000 years in a place far, far from here, we’re still using the same thing. There is actually one thing early in the film that Denis Villeneuve picked, which is that you see a guy playing bagpipes. I thought that was brilliant because that’s a timeless instrument. When you hear it, I replaced the tune by Guthrie Govan, the world’s greatest guitar player. “Can you sound like bagpipes?” “Yes, I can.” I forgot to mention this to Denis, and we were at some Q&A in New York, and I said, “That’s Guthrie playing guitar.” And he was quite shocked. He said, “Are there any other things you forgot to tell me?”

Favorite piece of music that didn’t make a film’s final cut

If it’s a favorite piece of music, it’s probably good enough to end up in the film. But I found a tape not too long ago of 48 main themes for The Lion King. It wasn’t as good as what we ended up with but they were not bad. At the time, I didn’t want to do fairy-tale movies. It’s great to be wrong. I was going, “I don’t like Broadway musicals,” and Disney said, “We guarantee you this could never become a Broadway musical.”

Most expensive studio equipment you own

I have Tangerine Dream’s old Moog synthesizer, which was given away by them because they didn’t want to use it anymore, and now you can buy a house with it.