There were two special occasions for the Smashing Pumpkins this year. The first was the 25th anniversary of the band’s album Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, a ridiculous 33-track monument to Gen-X sadness that debuted atop “The Billboard 200,” won a Grammy, and spawned a handful of era-defining singles: “Bullet With Butterfly Wings,” “1979,” and “Tonight, Tonight.” The second was the release of CYR, the band’s second double LP that pretends to be a pivot to synth that follows 2018’s Rick Rubin–produced reunion album, Shiny and Oh So Bright, Vol. 1/LP: No Past. No Future. No Sun. (The “reunion” was of original drummer Jimmy Chamberlin and guitarist James Iha, both of whom joined the same Pumpkins album for the first time since 2000. They also appear on CYR.)

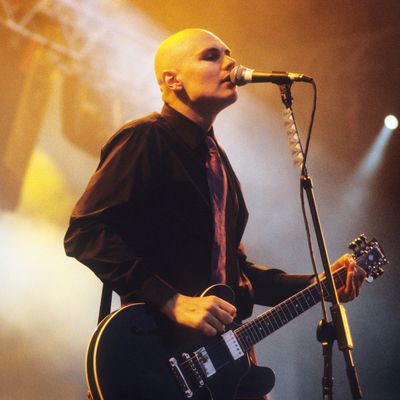

Both projects were crafted by the band’s primary songwriter and mastermind, Billy Corgan, who, at 53, remains the sole consistent member of the band — as well its most indulgent — for better or, to many critics and some fans, for worse. Over video chat, he spoke confidently and with a strong sense of narrative, as if every dud and 23-minute B-side were not only intentional but necessary. He also remains alternative’s grumpy populist, a self-proclaimed free-market libertarian capitalist who taught a generation how to feel sad at Disneyland — figuratively and literally. Mellon Collie is how many fans wish to remember the Smashing Pumpkins. CYR is Corgan’s reminder of who the Pumpkins actually are.

But Corgan is at peace with the band’s “contemporary” sound: “Usually, I feel a lot more anxious,” he says about the new album, “but I think because so much music has come out already, ten songs, I feel pretty relaxed about it. The reaction has been really positive. I think letting people acclimate to the new music over time has been a good strategy.”

Besides giving an update on upcoming sequels to both Mellon Collie and 2000’s Machina/The Machines of God — he promised that both projects will sound like a “kitchen sink” of what fans love about the Pumpkins — Corgan was gracious enough to walk us through the highs and lows of his beloved band as well as how the new album stacks up.

Favorite song on CYR

If I had to pick one, I’d probably pick “Wrath.” The hardest thing in the world is write a simple song that’s effective. I think “Wrath” falls in that category. I think it’s one of those songs where I think I pretty much knew what it was gonna be like when I started. I write a lot of music that’s situational, and occasionally I write a song that’s more personal. “Wrath” sort of falls into that.

CYR’s trademark Smashing Pumpkins moment

Probably a song called “Wyttch.” It’s the interesting combination of guitar and irony. There’s kind of a nascent irony in the whole thing, which has always been our sort of approach with heavy guitar rock.

When people were hearing the early songs off the record and hearing a lot of synthesizer, they were thinking that there was gonna be no guitar. When that song came out, all that talk stopped. Obviously, that band is still very much alive, the “mean guitar” band. My only admonition was that we needed to make a contemporary record. I didn’t care how we did it. If it had been all acoustic, I would have been fine with that, too, as long as it felt contemporary. I just didn’t want to fall back into the trope of “We’re the Smashing Pumpkins, and this is what we do. Here’s our music.” I think that’s a dead path for us.

For example, people may not think of it when I say contemporary music, but one of the features of contemporary music is that time is compressed. People are so used to clicking off things that they’re not interested in. I grew up that you put on a record and you put the needle down. If you wanted to change a song, you had to get up off the couch, flip the needle, and go to another song. Now we just reach over to our phone and we click something. You have to assume that time is at a premium in a contemporary song. You don’t have 45 seconds for an intro, you know? You got to get into it.

Smashing Pumpkins song that sounds the most like Chicago

It’s probably “Tonight Tonight.” I wrote the song for Chicago. It’s kind of like my love-letter postcard to my hometown. I was born on the lake, like I was literally born on the lake. The hospital’s long gone. But I live on the lake. The lake is the symbolic thing for me of the city. There’s a line in the song about “city by the lake.” It’s like when I’m writing the scene, it’s the place in the movie where you’re standing next to the lake. It was literally the image in my mind when I wrote the song.

Best Smashing Pumpkins song for wrestling

That’s a terrible question. I don’t think our music works out very well for wrestling. Wrestling tends to like jarhead-metal riffs for themes. We really don’t have much of that, unfortunately. I think we fail in the wrestling-theme department.

Your kids’ favorite Smashing Pumpkins song

When they were younger, they liked the “Bullet” video a lot. They used to watch that a lot. They kind of like “scary dad in the video” stuff.

Your go-to trick for songwriting

If you start a song in a minor key, you go to a major chorus. That’s the simplest trick in the world. If you start in E-minor, you go to G-major for the chorus. If you start in a major key like G-major, then you would want to try to modulate up, so if the verse is in G-major, then you would modulate up to, say, B-flat major for the chorus. Modulation is the ultimate trick in songwriting.

Like, “Jellybelly” is in major, believe it or not. It’s major with a flat A7. The guitar is tuned a half-step down. It’s actually tuned to an open C-sharp chord. All the ascending riffing and stuff is all major. That’s a different trick, in that if you start in a particular key, you modulate for the bridge or whatever, then when you modulate back to the chorus, you modulate back to the original key. You want it to feel like it lifts.

Best use of the “Pumpkin Chord” (playing the 11th fret on the A-string while playing the open top E-string)

We basically stole that from Jimi Hendrix. But Jimi Hendrix probably stole it from Wes Montgomery. It’s just the idea of using octaves, but with an open string. Easiest way to do it is to have a guitar tuned to E and you play that, like you said, the 11th fret with the octave. You hand mute the third string, the D. That’s what we jokingly call the Pumpkin chord, because I wrote a lot of songs off of that.

“Cherub Rock” off Siamese Dream is a good example of how to use that chord. It opens basically on the tonic — so basically E against E. It ascends up through the scale, and then the riff is [sings the “Cherub Rock” riff]; it’s the third — but it’s basically how they do Indian music to create tension using the other notes.

We talk a lot in the studio when we’re writing about trying to “lift.” “Cherub Rock,” for example, is an example of where you’re working in two keys, E-major and D-major, but through the cycling of the keys, it keeps feeling like it goes up. My dad pointed out to me when I was young the idea that resolving in music will feel flat, meaning emotionally flat. When you play a solo — duh duh duh duh duh duh duh duh duh duh — and you land on the root note, it feels a bit flat. By landing on other notes, you create tension, right? You do the same thing with chords. You don’t necessarily resolve things. The human response to unresolved music is tension, which creates attention, human brain attention, and so you just work with that, then you try to avoid resolving at all costs.

Most surprising legacy of Mellon Collie

For me, it’s kind of a negative. I see where people have tried to kind of minimalize [its] accomplishment. You know, in essence, trying to cement a narrative about the band, which isn’t true. Somehow that album becomes the thing that they use it to do. Hipster writers really like Siamese Dream, right? They want the band to end after Siamese Dream. It’s kind of weird. But Mellon Collie was by far a bigger record and a far more influential record. Because we live in this world now where people want to create whatever reality they have in their mind, they will basically create data that doesn’t exist to shore up their arguments. Somehow Mellon Collie has become the front line in that argument. It’s very strange to me. If you create an album that was that big — I think we had six hit singles off the record; it’s one of the biggest-selling record records of all time — how do you erase that from history? But we live in a world now where, depending on the way people Google, you can erase things — you can just pretend that things didn’t exist. But they did.

Smashing Pumpkins album that 21-year-old Billy Corgan would be the proudest of hearing?

It would be Adore. I was going through a lot of grief. My mother had died. I made the choice to put those feelings into words or music, but I also made the choice to make an album that was sort of more honest to where I was in my musical life, instead of doing what was expected of me. And I think 21-year-old me would have been proud that I didn’t sort of sell myself out completely to the forces around me.

A piece of praise of your music you don’t agree with

The real trick is to also disregard praise. You have to put yourself in a position where you know who you are and you know what you’re doing, and other people’s reactions — they certainly can be respected, but they shouldn’t have anything to do with the way you operate. I don’t really hear praise. I certainly hear when people compliment me. It doesn’t land. It just doesn’t penetrate, because I had to shut all that out. So, unfortunately, if there is praise, I don’t know what it is. Because it always seems to come with an asterisk or something in my mind.

I think the band’s story is so wrapped up in critical confusion that it’s almost impossible to untangle those things. Going back to what I was saying about Mellon Collie, you have a clear win. I mean, it’s a clear win. It was a huge album. It was an artistic breakthrough. The band was very successful. Some would argue the band was never bigger than it was at that particular point. And now we have people basically disregarding this achievement. Look no further than that. I sort of don’t know how to categorize that.

And by the way, hipsters hated Siamese Dream when it came out. Now the hipsters love the record. It’s crazy. We live in a time of invented reality. Some of my friends call it the post-truth era. You know, we live in a post-truth era.

The next album that’ll be embraced by the hipsters

It would probably be my first solo record, TheFutureEmbrace. It’s a really good record that was completely disregarded at the time. It’s the perfect setup. Here’s an overlooked gem. Who can be the first to claim it?

The music video that changed the meaning of a song the most for you

Probably the “Tonight Tonight” video. It sorts of sentimentalized something that I maybe wouldn’t have gone out of my way to do. Now that it exists, I sort of see it that way.

I think [the directors Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris] did a good job. I think it framed something about the song that made it sort of more universal or sweeter than I might have done. I appreciate that in hindsight, but at the time, I didn’t totally understand it. If you think of the lyrical connotation of the song, the person is asking someone else to believe in them. I’m not saying, “Thank you for believing me.” I’m saying, “Could you believe in me?” or “Would you believe in me?” There’s still the tension of “Is this going to happen?”

Favorite bad review

What I read a lot back in the day was criticism of our postmodernism, criticism of our restlessness, criticism of my voice, criticism of our desire to play rock, heavy rock — it’s just a lot of things that were attacking the immutable characteristics of the band. If a reviewer says in the first sentence, “I hate this guy’s voice,” where do you go from there? You’re going to hate everything. Even if it’s a well-executed song or it’s the best use of that voice in a particular way. That’s what I remember, just reading a lot of things that you would just sort of say, “Well, then why?” Why would this person even review the record? Why didn’t they give it to somebody who at least had an open mind or had never even heard the band or something?

You know what, here’s a good review. Here’s a good bad review. It’s not a record review — you know Bob Lefsetz? I did a thing a few years ago where Cheap Trick was playing Sgt. Pepper’s at the Hollywood Bowl. I was invited to be one of the guests. Onstage, I got to sing the John Lennon song “Julia,” about his mother, with Robin Zander, the lead singer of Cheap Trick. It was really beautiful. And Bob Lefsetz writes: “I normally hate Billy Corgan, but here I have to admit, he was good.” Stuff like that. He had to qualify [it] by saying he normally hates me. He can’t just write, you know, “Billy Corgan, appearing here in not his normal vampire guise, did a nice rendition of ‘Julia’ with Robin Zander.” It was like: “Normally I hate this guy. But he did good here.”

More From The Superlative Series

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music