Suspended over FDR Drive, Alynda Segarra pressed against the harsh November wind and described their final moments with their father. “It was just me and him,” they said. Traffic whirred below the footbridge connecting 6th Street and East River Park as they recalled arriving at a Bronx hospital, in February 2023, with their guitar and a trove of poetic songs that would become their ninth album just in time to play them at Jose Enrico “Quico” Segarra’s side before his death from a heart attack. “The nurses were telling me he could hear me even if he couldn’t respond. It felt like he was blessing the album.”

A month later, Segarra, who performs as Hurray for the Riff Raff, showed up to producer Brad Cook’s North Carolina studio to record The Past Is Still Alive — their latest and most autobiographical record, spinning their history as a train-hopping Nuyorican teen-punk runaway into an epic travelogue and outlaw collage — carrying a vial of Quico’s ashes. “You don’t have to die if you don’t want to die,” Segarra sings, tough and tender, on “Alibi.” Originally a last-ditch plea written to a friend in the throes of addiction, it took on a new life as a grounding bid to hold the memory of their father. “It’s so huge — there’s no end to how this person should be commemorated,” they said of Quico, who was a Latin jazz musician and a Vietnam vet.

To live within the idioms of the old, weird American music is to know that death is not the end. Segarra arrived at this fact 20 years ago as a hardscrabble street musician in their adopted home of New Orleans, investigating Delta blues, Appalachian folk, and traditional jazz — all early stops on their itinerant path to becoming one of America’s best songwriters. Their literary folk-rock has always conversed with the past while attuned to the present. But it has never sounded more realized or free. The Past Is Still Alive traverses queer landmarks like the Stonewall Inn and the Castro, and beatnik haunts like City Lights Books and graffitied trains, carving out a subcultural topography amid a mythical American landscape of highways, pueblos, and Buffalo herds. They sing about dumpster diving and “hiding from the cops in Ogallala, Nebraska.” They turn misfit heroes and lost friends into self-described “monuments,” like Lucinda Williams’ “Drunken Angel” before them. On the prayerlike centerpiece “Colossus of Roads,” named after the boxcar graffiti legend Buz Blurr, Segarra sings, “Eileen, I must be living twice,” a reference to the countercultural poet Eileen Myles and a reminder that there are ways of being an artist beyond what is prescribed.

Hurray for the Riff Raff stakes claims to American myths while inherently critiquing them. They stare out from the cover of The Past Is Still Alive like a James Dean cowboy, and as their restless new songs audaciously allude to Dylan and “that scene at the end of Titanic,” every coolly phrased note voices a class-conscious irreverence. “When you think of the Band or Dylan, it’s so straight and so male,” Segarra said. “What I love about playing folk music is fucking it up. I’m queering it.” They wrote “Colossus of Roads” in the wake of the 2022 shooting at Colorado’s Club Q, and said the AIDS activists of ACT UP and Gran Fury were top of mind while penning its cascading verses: “Say goodbye to America / I want to see it dissolve,” they sing with a squint. “I can be your posterboy for the great American fall.” “It was this feeling of not wanting to carry a liberal hope anymore and say, ‘I don’t have an answer, and I don’t think everything’s just gonna be okay,’” Segarra said of that lyric. “But this idea of America as a place where we all toil, while extremely wealthy people get to go to Mars — this is over.”

Segarra was raised in the Bronx by their aunt (Quico’s sister) and uncle after their parents split, and their politician mother — who, incongruously, served as a deputy mayor to Rudy Giuliani through the 1990s — left the picture. “I didn’t hear from her at all, but it was a lie I had to keep up because it would be bad for people to find out she doesn’t talk to her kids.” Segarra maintained an imperfect relationship with their father, and when they visited Quico as a child, music was their language. “He would play piano and I would sing show tunes,” Segarra happily recalls. “It was the cutest shit ever.” One night, the duo performed “Que Sera, Sera” and “You Light Up My Life” at a community open mic at the Puerto Rican Theater. “We brought the house down. There was a standing ovation. We got on the local Bronx news. I remember being like, This is it, show business baby! I was 6.”

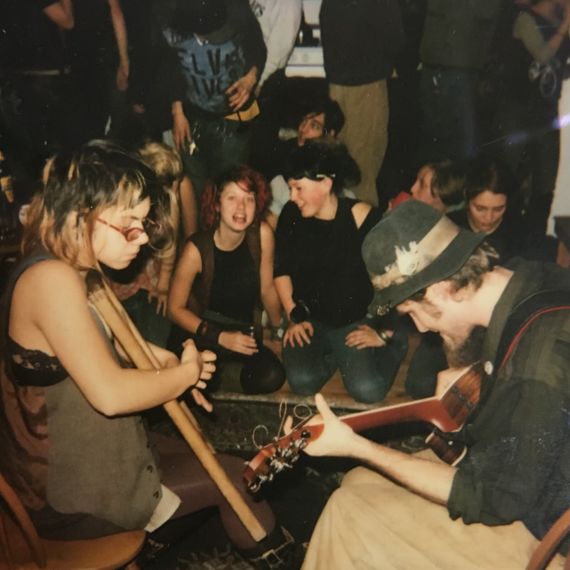

By high school Segarra had turned goth and brooding. They issued a fuck-you to the world’s oppressive beauty standards by “wearing dog collars and listening to the Dead Kennedys.” After tenth grade, they were “failing out of school,” and eventually opted out. “I felt like I was just a really big problem,” they said. A few months later, Segarra took a Chinatown bus to Philadelphia with friends to see the folk-punk band This Bike Is a Pipe Bomb and met a crew of “wholesome” mid-20s squatters who had dubbed their autonomous zone the Wasteland. “Come live with us!,” the squatters said. With a backpack and sleeping bag in tow, they headed to Philly and spent a month crashing there before cobbling together enough cash for a Greyhound ticket to San Francisco, where they started hopping trains.

The very tenor of memory — the fractured process by which experience reconstitutes itself — makes up the oxygen that The Past Is Still Alive breathes. “Snake Plant (The Past Is Still Alive)” describes Segarra and Quico’s summertime minivan trips to see relatives in Florida, evoking sense memories like the cinnamon scent of their father’s cologne, and the mangos and lemons of an idyllic Southern setting that triggered his post-Vietnam PTSD: “I know your face, I know your smell,” Segarra croons. “I know that you were living in hell.” A few beats later, the song’s fragmented childhood recollections give way to scenes of Segarra’s escape from home at 17:

Campfire on the Superfund site

Garbage island, fuckin in the moonlight

Play my song for the barrel of freaks

And we go shoplifting when it’s time to eat and

They don’t even really know my name

I’m so happy that we escaped from where we came

The outline of Segarra’s biography has always been a part of their story, but they’ve been reticent to candidly narrate or “commodify” these underground rebel stories until now. “I was very protective of train riding and the punk scene and the squatter scene,” they say. “I would talk about it, but it’s also so sacred to me. I didn’t want to allow people to turn it into a product. But in the pandemic it really hit, like, This is my life. It’s gonna end at some point. And I want to remember.”

One week before he died, Quico mailed Segarra a package of CD-Rs containing “literally every recording” Segarra had ever made. There were ramshackle records from their self-described hobo bands like Dead Man Street Orchestra, for which they learned banjo and washboard to busk in the French Quarter. There were the unruly old-time jazz ensembles Loose Marbles and Tuba Skinny and their country band Sundown Songs. There was all the music Segarra had made since 2007 as Hurray for the Riff Raff, including 2012 bluesy breakthrough Look Out Mama and their ambitious 2017 concept album The Navigator, which explored their Nuyorican roots (and which Segarra is now adapting for the stage). “All of The Navigator was me trying to get him to think I was cool,” they joked of their dad. “He was always super supportive, but a little like, What the fuck is this country shit?”

Segarra’s father was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico and grew up in the projects in Chelsea before settling in the Bronx. When a teenage Segarra was first exploring the East Village in the early 2000s, “I thought I was getting away,” they said, but eventually learned their dad “used to get high and play jazz on rooftops” around Tompkins Square Park. “My dad had already done everything cool.”

Sitting on a bench at a deserted East River Park, Segarra and I stared out at Brooklyn discussing those anarchic teen years. “My life used to be so outside,” they said. “I have a very vivid memory of sleeping under a bench here.” They laughed and recoiled. “Oh my God, there were so many rats.”

As a kid, their regular trek between the Bronx and the East Village on the 1 train took two hours each way. It was on those long rides with their Discman that they began writing poems. Trains are as essential to the folk imagination as fascist-killing acoustic guitars, but before Segarra was crisscrossing the country on freights, their creativity and defiance took root on the subway. “Growing up and feeling like prey on the train and in the street, I had this energy in me of very fierce self-preservation, like Jedi-mind-trick stuff,” they said. “I felt that urgency my whole life.”

While Segarra admits that those “outside” years in New York often took the form of loitering in Tompkins and drinking fortified wine after hard-core punk matinees, it was also the province of constant protest. They marched against the World Economic Forum and the 2004 Republican National Convention, and participated in consistent Critical Mass and antiwar actions after the invasion of Iraq. The latter was stoked by Quico. “He was so antiwar and so straight up with me: ‘Black and brown kids are always on the frontlines. They always treat them like they’re disposable,’” they recalled. “It felt so clear to me because of him.”

Segarra’s best friend, Amelia Jackie, who first met Segarra when they were a 16-year-old singing in the acoustic punk trio Hotdog Is My Hero, recalled those formative actions. “We were always going to big demos — that was one of our big purposes in life,” Jackie said. One of the first times they hung out, “Alynda and a big group of people had been arrested at the RNC and spent the night in jail.” They eventually went over to Jackie’s place on the Lower East Side, where Jackie played a song she’d written — a performance that inspired Segarra to strike out on their own. By the mid-2000s, Jackie and Segarra were busking and hitchhiking and sleeping in shrubbery, but also writing songs that processed their mutual experiences as survivors. Music felt “very much like protection” then, Segarra said. By Jackie’s measure, Segarra’s first great song was 2008’s “Daniella,” “a feminist anthem about protecting your friend from an abuser.”

“Alynda has a really strong spiritual connection to music that is informed by politics and it lives inside of them,” Jackie said. “They have carried that through their whole career.”

Segarra seems to write with their eyes wide open. That impulse sets them among music’s most consequential opposition artists today, with songs like their 2014 feminist murder-ballad critique “The Body Electric” and 2017’s anticolonial “Rican Beach.” On The Past Is Still Alive, “Snake Plant” enacts a mid-verse mutual-aid banner drop when Segarra suddenly proclaims, “Test your drugs, remember Narcan / There’s a war on the people, what don’t you understand?”

But Segarra’s spirit of protest reached its apex on the 2017 rallying cry “Pa’lante,” a triptych fight song from The Navigator that borrows its structure from the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life” and samples Pedro Pietri’s 1971 poem “Puerto Rican Obituary.” Reimagined to voice Puerto Rican working-class struggle and the immigrant experience in America, “Pa’lante” calls out to historically oppressed people across history: “From el barrio to Arecibo / ¡Pa’lante! / From Marble Hill to the ghost of Emmett Till / ¡Pa’lante!” The title, inspired by the newspaper published by the Young Lords, an anti-imperialist Puerto Rican community group of the 1970s, is an affirmation meaning onwards. “I really believe in ancestors working through me,” Segarra said, describing the intensity of recording “Pa’lante” as almost ceremonial. “That song continues to feel like a burden lifted, like ‘Thank god I did one of the things I was supposed to do in this life.’”

Before the poet Eileen Myles knew their 2015 anthology I Must Be Living Twice was referenced on “Colossus of Roads,” they saw Segarra play for the first time in Marfa, Texas, and felt an immediate kinship towards the queer, working-class voice that also lives in their own work. “There was an elegance, there was something raw, it was their own language. It had a politic,” Myles said. “It was just all these elements where I’m like, you’re my people. I got the political sensation from their language that class is something that is a vernacular and you talk through it and people hear you. The rawness I feel in their work comes out of all those realities that then bring you to the next political situation.”

At the sold-out Brooklyn stop of their The Past Is Still Alive tour, in March, Segarra closed with a blazing incarnation of “Pa’lante,” intercut not with “Puerto Rican Obituary” but with a recitation of Gazan poet Refaat Alareer’s “If I Must Die,” written days before his death in 2023 by an Israeli air strike. In front of a stage banner that put “HFTRR” inside the crisscrossed quadrants of the classic New York hard-core logo, Segarra stomped open the song’s rave-up final movement, channeling Patti Smith’s fire and offering the lucidity that comes with confronting reality: “To the resistance in the streets / ¡Pa’lante!” they belted, with gritted-teeth resolve that punched out in every syllable. “To Refaat Alareer / ¡Pa’lante! / To the poets of Palestine / ¡Pa’lante! / To all who came before, we say / ¡Pa’lante!”

The day Segarra recorded “Pa’lante,” in 2016, emotions were high. Segarra’s paternal grandmother had died around the time of writing The Navigator, and “so much of it was about trying to honor her legacy and honor all that my family had been through, trying to heal ancestral wounds of erasure and belittlement about Puerto Rican identity and experience,” Segarra said. “I felt like I was biting off more than I could chew with the whole record.” But Segarra rose to the challenge. Recording outside San Francisco in Stinson Beach, the record’s producer encouraged Segarra to take a walk to the water for a breather. “I had been told by some friends about honoring the ocean by offering it a watermelon,” Segarra said. “So I went and I brought a watermelon to the ocean. I just came with a lot of humility and talked to spirits, and was like, I’m really trying to do this song. And it’s not about me. It’s for a lot of people, and it’s for people that are not here anymore. And I just really need help.” Then they went back and recorded a song in which the past would be reborn eternally.

In all of Segarra’s best work — in their tapestries of justice, beauty, ancestry, and adventure — history alchemizes the future. The Past Is Still Alive clarifies those coordinates, or as they sing on its scorched closer, “I used to think I was born into the wrong generation / But now I know I made it right in time / To watch the world burn with a tear in my eye.” The miracle is that Segarra doesn’t look away.