It’s not until we’re at the bottom of the 30-foot ladder, necks craned up at the bright West Texas sky, that Eileen Myles casually mentions that she’s afraid of heights. The rusty ladder is the only way to get to our destination, an old spring-fed railroad tank off a ranch road. Myles recently bought a small stucco house in Marfa, about 20 miles from here, and splits her time between rural Texas and the East Village apartment she’s lived in for four decades. Fortunately, the 65-year-old poet doesn’t seem inclined to let fear slow her down. She grips the railing and begins clambering up. Once at the top, she drops into the water and emerges wearing a broad, satisfied grin.

Four decades into a writing career spent decidedly and defiantly in the underground scene, Myles is having an unexpected bout of mainstream success. Her first decade-spanning collection, I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975–2014, will be released by HarperCollins on September 29; that same day, the publisher will reissue Myles’s influential, out-of-print 1994 novel Chelsea Girls.

Her influence is cropping up elsewhere as well. In the second season of Transparent, Cherry Jones plays a poet loosely based on Myles — two poems used for the show were actually written by Myles — and Myles also has a cameo role. The new Paul Weitz film, Grandma, stars Lily Tomlin as an irascible lesbian poet in her mid-60s and opens with a quotation from Myles. (“Time passes. That’s for sure.”) “She’s badass,” Weitz said when I asked him about Myles. “I don’t mean to be flippant, but she’s an ass-kicker. She’s incredibly literate, with an aspect of punk rock. That’s what I was hoping to capture with Lily Tomlin’s character — that somebody in their 60s can be more edgy than somebody in their teens.”

Myles’s first mimeographed book of poetry came out in 1978; since then, she’s published 19 books of fiction, poetry, and criticism. In 1992, she campaigned as an “openly female” write-in candidate for president. She toured the country as part of the lesbian, feminist spoken-word/performance-art group Sister Spit. Part of Myles’s enduring appeal is that she’s experimental in the true sense of the word; every time you turn around, she’s up to something different. “I keep trying to do something that will look good with everything,” she says, treading water. “But then the world changes and I have to make something entirely new.” She just finished her first sci-fi book, about a time-traveling dog. She considers it a memoir.

Myles’s narrators often share the broad outlines of her biography but in a slightly skewed fashion. One of her most famous pieces of writing, “An American Poem,” begins:

I was born in Boston in

1949. I never wanted

this fact to be known

And then, midway through, proclaims, “Yes, I am, / I am a Kennedy.” Myles is not a Kennedy. (The poem apparently still confuses some people.)

Chelsea Girls was her first novel. Like the novels that followed, the story unfolds through a series of brief vignettes told in short, immersive bursts (“I thought of them as films just as much as stories,” Myles says, “or mistakes, or embarrassments — things I needed to exorcise”) about a character named Eileen: her tumultuous childhood in Massachusetts; her moving to New York to become a poet in 1974; her early, drunken, romantic years; her reckoning with her queerness and her substance issues. In one section, Eileen gets her photo taken by Robert Mapplethorpe. In another, she assists the ailing New York School poet James Schuyler, who is living in the Chelsea Hotel in a kind of glamorous squalor.

“I thought Chelsea Girls was going to change my life,” Myles says. It didn’t. She remained an outsider — albeit a frequently name-checked and influential one. Even as the book went out of print, echoes of its biographical playfulness showed up in faux-memoir novels by Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, and Ben Lerner. And she’s continued to pick up fans; Lena Dunham, Kim Gordon, and Maggie Nelson all blurbed the new books. It hasn’t hurt that Myles is very good at both Twitter and Instagram. “With Instagram, you’re captioning a moment,” she says. “Twitter is the caption without the image. Even if it’s there, the words come first.”

Part of Myles’s allure for a younger generation is that she seems to have gotten away with precisely the kind of New York life that doesn’t seem possible anymore — living cheaply, maintaining only glancing alliances with major academic institutions, and earning a living by making art pretty much the way she wants. “It helps that I was queer, it helps that I grew up working class,” she says. “I wasn’t afraid of being poor. I didn’t want to live in a big house. I’m the perfect size for poetry. I can move around.”

Lately, Myles says, people have started using the word legend when talking about her life and work. Isn’t it weird for her to find herself installed in this 21st-century version of a canon after spending her whole life outside it? “I always aimed at being a legend,” she tells me, grinning. “In the ’70s in New York, Allen [Ginsberg] was treated like a legend. But he was still engaged — and it was always a thrill when he would show up at your reading, like a kind of validation. So it’s like there are people whose work you respect, and you want to succeed them.” I Must Be Living Twice is a 368-page bid for that legendary status. “Women’s collecteds are smaller than men’s collecteds,” she points out. “And collecteds usually come out after you’re dead. So it’s great I have a publisher who is fine with a big one. And “I like having it all out now, so I can go on. It’s like shedding all this work.”

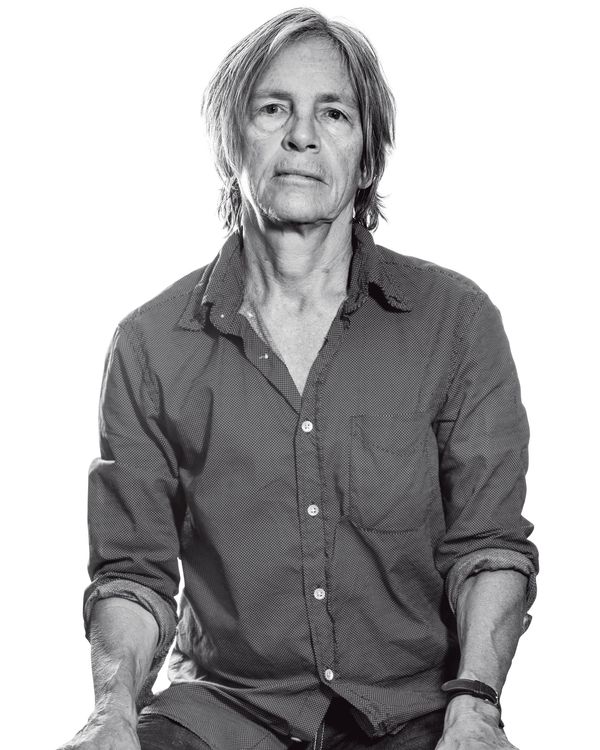

Myles’s transition to a mainstream publisher hasn’t been seamless. Editors attempted to correct some of the punctuational and grammatical exuberances of her work. And Myles and her publisher spent weeks debating possible cover images for both books. Eventually, they found common ground: The reissued Chelsea Girls will feature a photo of Myles from 1980 taken by Mapplethorpe; I Must Be Living Twice uses a photo of Myles taken by Catherine Opie. In the Mapplethorpe photo, Myles peers out from behind a thick shag of hair, with eyes that look both knowing and slightly suspicious. (She was hung-over.) In the Opie photograph, Myles is older, no longer wary. She sits on a stool in front of a deep-red background, looking straight ahead, a lesson in powerful posture.

As we swim and talk, I start to realize that despite her avant-garde bona fides, there’s something almost old-fashioned in Myles’s dedication to the capital-R romantic life of the artist, with all its attendant economic and emotional turmoil. When she was young, she moved to New York with the explicit goal of being a poet, and she never decided the idea was a childish notion she had to get over. And then she became a poet.

Sometimes, Myles keeps her momentum up by, as she puts it, “fleeing.” “I like it in Marfa, because it doesn’t look like anywhere else for me,” she says. She also hopes the Marfa house will serve as a refuge from the overstimulation of life in New York. She tells me about a recent evening involving gallery openings and performance art and cheap late-night dumplings, during which she happened to run into both Kim Gordon and Sofia Coppola. Nights like that make New York worthwhile, she says. They also leave you feeling ravenous: “You get greedy for more,” she says. “More and more and more.” But as many times as she’s left the city — for New Mexico or San Diego or, now, West Texas — she keeps coming back. “New York is like a tether,” she says. “You know how Gertrude Stein wrote, ‘I am I because my little dog knows me’? Sometimes I feel like I am I because New York knows me.”

*This article appears in the September 21, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.