Everything in Constantine is washed with green, as though the whole world were unwell and not just the film’s terminally ill hero. The color-grading choice was particularly popular in movies at the turn of the millennium, a sickly tint that conveyed metropolitan gothic sensibilities and disaffection while amping up the physical sallowness of already-pallid leads. The Matrix is the stone-cold classic, and Dark City has its devotees (Roger Ebert notable among them), but for me, Francis Lawrence’s directorial debut about a psychic consultant has always been the best distillation of this aesthetic. Constantine has such a palpable appreciation for the details of the universe it puts onscreen — from the stained subway tile lining John Constantine’s kitchen to the oxblood club chairs in a church to the lock of hair that keeps escaping to flop over Keanu Reeves’s forehead — that any grander point becomes incidental.

Not that the story is lacking! Constantine is deeply pleasurable in a way that has become easier to admit as the film, which just crossed its 20th anniversary this year, has been removed from the context in which it was originally received. In 2005, Constantine was regarded as a Matrix knockoff and an unsatisfying run on a DC Comics property; fans of the former saw something a little too familiar in the sight of Reeves playing another gifted type capable of piercing the veil to see the true nature of reality, while fans of the comic-book character were miffed to see the blond Liverpudlian turned into a brunet Angeleno. (Constantine co-creator Alan Moore, as is his tradition, disavowed the film.) It can be hard to accept now that Reeves has been elevated to our battered saint of action cinema, but he was a sticking point for many viewers at the time. He was treated as a stand-alone punch line about wooden acting, to the point where a satirical stage version of Point Break that premiered two years earlier cast an audience member, reading off cue cards, to play Reeves’s part.

To be fair, Constantine isn’t one of Reeves’s strongest turns — the Valley-boy curl of his voice doesn’t lend itself well to a script heavy on mordant quips, and despite being a smoker himself, he approaches the character’s fatal cigarette habit with the staginess of a high-school sophomore attempting a rock-and-roll rebrand. But Reeves was also at the height of his astonishing beauty, stalking around a moody L.A. in a rumpled dress shirt and loosened black tie as though perpetually winding down from some more professional day job that doesn’t exist. He’s a modern-day version of a Victorian consumptive, coughing up blood and covered in a light sweat that just registers as an otherworldly glow.

Reeves might not have made sense for the role, but he made sense for the movie, a contradiction that wouldn’t be permitted in the years to come, when IP of the sort on which Constantine is based would become load-bearing, freighted with the needs of the geek faithful as well as corporate strategy. It is precisely a loose commitment to fidelity that allows the movie to be good, because its priorities are with its own existence as a feature rather than as an adaptation or some baroque work of brand building. Constantine wasn’t a flop at the box office (it grossed over $230 million worldwide), but its reappraisal as a cult classic owes less to its theatrical release than to its regular presence on cable in the years afterward, where it could slough off its baggage and be seen as the solid entertainment it is.

It really is entertaining, an urban fantasy about an ongoing, unseen war between God and the Devil that’s just a series of riffs on noir themes, with angels and demons serving as stand-ins for nefarious businessmen and corrupt officials. Constantine himself, a self-appointed bounty hunter dispatching misbehaving beings from the mortal plane in hopes of earning a way out of his own damnation, is a private eye in supernatural trappings, living in an office-cum-studio where the lights from the street below can cast ideal shadows onto his brooding face through the slats of the blinds.

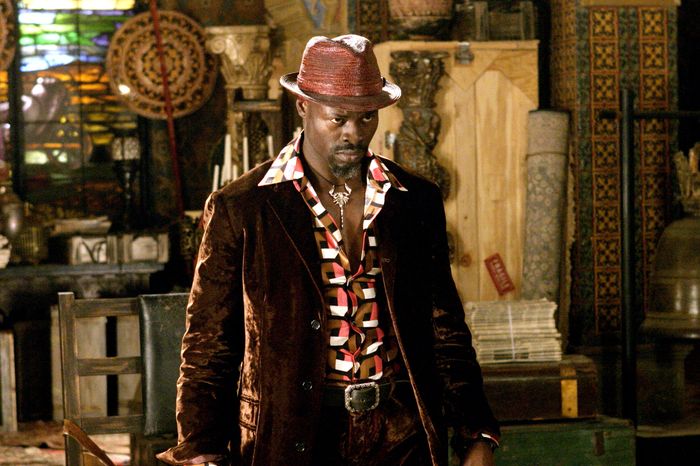

Opposite Reeves is an equally fetching Rachel Weisz playing identical twins years before her Dead Ringers remake and serving as both the skeptical client and the ethereal victim whose death, a swan dive from the roof of a psychiatric hospital, becomes a haunting motif. But it’s the supporting cast that makes the movie, an orgy of distinctive faces crammed in but never taken for granted — Pruitt Taylor Vince as a jittery alcoholic priest who can hear voices from beyond the grave, Djimon Hounsou as an imperious witch doctor turned bar owner in a fedora and fur collar, a baby-faced Shia LaBeouf as Constantine’s impatient protégé, and Max Baker as a twitchy dealer in occult objects who, for reasons unknown, works out of the space behind the lanes of an abandoned bowling alley.

And that’s before we get to the really prime stuff, like Bush’s Gavin Rossdale giving a standout turn as Balthazar, a demon hiding beneath that pretty-boy Britpop façade and some buttoned-up corporate drag, sneering his way through evil deeds while flipping a coin across his knuckles. Or Tilda Swinton, still a relatively new quantity to American audiences, playing an androgynous angel Gabriel in a Windsor knot and wavy lob and beaming with the sort of toxic positivity a youth pastor might exude while suggesting a kid would benefit from conversion therapy. My favorite of all is Peter Stormare as Lucifer himself, floating down in a white suit and bare feet covered in tar like some infernal version of a southern roué whose eyebrows were seared off by the flames of hell.

There’s no fucking in Constantine — Weisz, in the role of LAPD detective Angela, is the love interest, but Angela is too focused on her dead sister to indulge in more than making eyes — but everyone else makes up for it by opting for the most flirtatious form of menacing possible, as though the intense, off-kilter allure of the assembled forces onscreen requires some kind of dispersal of erotic energy. Angels and demons alike can’t help but almost kiss Constantine in their attempts to ward him off, and Satan, between whispered threats, takes a moment to teasingly rub his foot on the dying man’s thigh.

Like Constantine, who rolls up his sleeves to display runes covering his forearms, Lucifer has tattoos peaking out from the edges of his tailored outfit. Ink under businesswear is a decent metaphor for the appeal of the movie as a whole, which may very much be an artifact of its time — you better believe there’s a club scene packed with lithe, ambiguously gendered patrons set to A Perfect Circle — but only reads as dated in the scattered scenes that rely on computer graphics, when hell is styled like the aftermath of an atomic bomb. Otherwise, the mystery at its core, which involves the death of a psychiatric patient and the miles-away discovery of the Spear of Destiny, is convoluted in a way Raymond Chandler would appreciate, the kind of twisty you can relax into, assured that it’s not anything you’re expected to truly follow. The journey, unfolding in a series of stylish encounters, is the point, not the destination.

Like a lot of people, I worry about my taste remaining lodged in my formative years and never evolving, about falling into a refrain about things getting worse that’s actually just an unintentional monologue about getting older and aging out of target demographics. But it’s true that so many of the satisfactions of Constantine come from past norms that can no longer be taken for granted. Lawrence was a music-video director who went on to have a solid studio career helming Hunger Games movies, and while he brings that slick visual style, his film also displays an underlying competence in more basic areas like casting and lighting that can trigger a RETVRN-esque pang. When the movie came out, critics dismissed it for being familiar or forgettable. “I will try to reconstruct some impression of Constantine, which all evidence, save my own memory, insists that I saw not long ago,” A.O. Scott quipped in the New York Times. Time actually proving it memorable may be more of a testament to what we took for granted in terms of basic standards than to the movie itself.

Constantine isn’t a total tour de force, but that’s also a big part of the joy of the movie and what leaves me unmoved by all the talk of a sequel. It’s not more Constantine I need so much as more movies like Constantine, ones you could stumble onto when flipping through the channels and serendipitously subject yourself to the wondrous spectacle of a winged Swinton in complicated cargo pants and an unmistakable viridian tinge, hissing “I will make you worthy of His love” as part of some standard Hollywood offering. Describe the movie and it sounds like schlock, but watch it and it pulses with life, proof of how much pleasure could be crammed onscreen within the bounds of a seemingly random studio project taking the form of a loose comic-book adaptation.

Exceptional things are easy to praise — it’s the normal stuff that could use help these days with more room to breathe and more personality. Constantine is nothing if not an ode to feeling like shit while wearing a sharp suit, and the powers behind everyday entertainment could stand to take note.