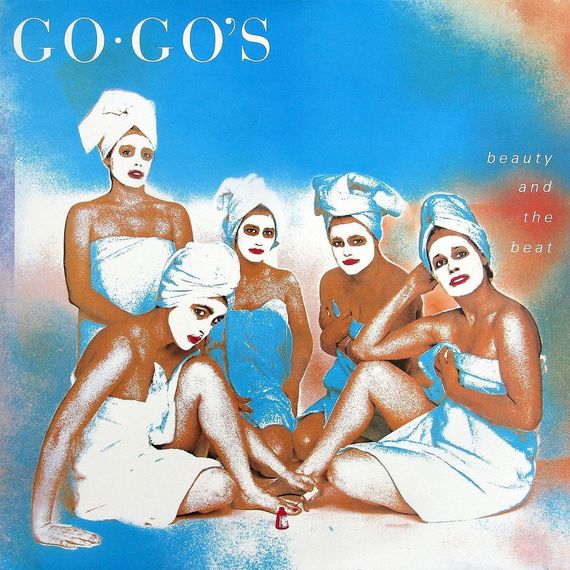

It’s not lazy hyperbole to state that in March 1982, the Go-Go’s accomplished something women in music never had: Their debut album, the irreverent and joyous Beauty and the Beat, hit the top spot on the Billboard charts months after its July 1981 release, cementing their legacy as the first all-women band who wrote their own songs and played their own instruments to have a No. 1 album. If “Our Lips Are Sealed” and “We Got the Beat” are the power-pop standards that paired perfectly with open convertibles, “Tonite,” “This Town,” and “Lust to Love” are their amorous siblings sweating at the Whiskey a Go Go before all the money and drugs came along, a sound that recalled the band’s roots in the Los Angeles punk scene. Beauty and the Beat’s success presented a moment of possibility for brazen sisterhood and musicianship on the biggest stages, even if their Billboard record still hasn’t been matched. (Nope, the Chicks don’t qualify. Neither do the Bangles. Haim came kind of close at No. 6.)

Four decades later, the Go-Go’s — consisting of vocalist Belinda Carlisle, lead guitarist Charlotte Caffey, guitarist Jane Wiedlin, bassist Kathy Valentine, and drummer Gina Schock — are getting inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this weekend with its newest class, a milestone that Carlisle (correctly) believes would’ve come earlier if it weren’t for “a lot of misogyny” within the Rock Hall. The honor’s belatedness hasn’t dampened Wiedlin’s enthusiasm for it, though; she’s eager to revisit the band’s early years, which led to Beauty and the Beat’s very existence. Wiedlin, who co-wrote some of the Go-Go’s most popular songs, indeed has a few regrets about that era — wisdom she says comes with age and acceptance.

Do you think the Go-Go’s could’ve come into existence without the L.A. punk movement?

Oh no, absolutely not. There was no way there was room for bands in the popular rock scene that didn’t have any experience and were all girls. So it was the punk scene, which most people, especially when they think of California punk, remember as being the hardcore pushing and shoving and all guys in a mosh pit beating each other up. That was not the beginning of the punk scene — the beginning of the punk scene was a bunch of outsiders, art-school people, women, people of color, queer people. It was this inclusive, small family of people who didn’t feel like they fit in with regular society. And that’s why the Go-Go’s were able to get together, prosper, learn their instruments as they went along, and learn how to write songs together.

I loved hearing about your punk metamorphosis in the documentary, like how people would cross the street when they saw you and how you “felt powerful for the first time” in your life. What was it about this movement that spoke to you so powerfully?

In 1976 I was in college studying design, and I was reading Women’s Wear Daily religiously. I saw these beautiful, huge pictures of kids in London, just dressed so outrageously. I thought, I don’t know what this is, but I want it. That’s how it all started for me. Then I started designing punk clothes and I found out there was a store on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood that was selling punk clothes. So I went to them and they took some of my designs. And at that time I met someone who was to become one of my closest friends, Pleasant Gehman. She was the one that told me that there was a fledgling punk scene in Hollywood and gave me a flyer for a gig.

The place was called the Masque. It was this horribly filthy and dark dungeony basement below a porno theater. And the plumbing was constantly breaking and overflowing and the electricity would go out. I mean, it was just a hellhole, but it became my little home. And it’s where the scene started for us in Hollywood. So it kind of grew from there.

You didn’t know how to play an instrument prior to the band’s formation. What drew you to the guitar?

When I was about 12, there used to be these little fun programs at the local parks where you could go and learn something. I actually took up folk guitar a little bit. For a few weeks I was playing the folk guitar. That was the whole of my experience. [Laughs.] So when I was 19 and the Go-Go’s started, I thought, Well, I used to do it. Maybe I can learn how to do it again.

Do any first impressions of your fellow Go-Go’s still stand out to you?

I remember when I first saw Belinda around the scene and she was so put together; everything was perfect. Her makeup was perfect. Her hair was amazing. She had the best style and I just immediately loved her. And as it turns out, she was the right person to be the lead singer. She had a ton of charisma. She’s beautiful. And then Charlotte, she was part of the punk scene but still had really long blonde hair. She totally looked like the quintessential California surfer chick, but she was such a badass on bass. We didn’t know her history, but she studied music in college. She knew all about music theory, and she played the piano and bass. Luckily for us, she agreed to start playing guitar.

What was the tour culture like for you all when starting out?

We played a lot on the coastline of California, and each town had its own very unique scene, even if they were right next to each other. Definitely in Hollywood and Los Angeles, where we were from, it was a very tight scene. Everyone knew each other and we were all like a family, so it was super-supportive. As we went up and down the coast and met other bands and became friends with bands in San Francisco and bands in San Diego, we found that it was the same kind of thing. It wasn’t intimidating or scary. It was just a lot of fun.

How was the coastline energy different in L.A. than, say, San Francisco?

I always felt San Francisco was more sophisticated and darker than the L.A. scene because we were at the beach. [Laughs.] So there was this sort of fun, sunny element to a lot of the bands — maybe a slightly more lighthearted tone. Certainly the Go-Go’s were very influenced by surf music, especially Charlotte. She possessed that genius combination of punk and surf for her guitar playing.

What else was influencing the band’s early sound?

We were all super-influenced by the ’60s, both in our style and our music. We obviously loved the Beatles. And when Kathy and Gina came in they loved the Rolling Stones, and we admired the ’60s all-girl singing groups. Even though they weren’t musicians, they were still super-cool. I think that definitely all went into our sound. We were very harmony heavy. I’ve always loved harmony since I was a little kid. That’s why being a background singer has been super-fun for me, because I love thinking up those parts. I love singing with Belinda — we create this one voice of sorts between us. But when the punk-rock scene started, that was the main influence on us, because all of a sudden you had these really, really energetic and crazy bands. Some of them were super-poppy, I would say, especially the Ramones and the Buzzcocks. We were very drawn to that idea.

“We Got the Beat” changed the trajectory of the band with its pop sound. How gradual was the transition away from punk to pop?

When Charlotte joined the band, we immediately started getting this bigger pop element. That’s when it started being sort of a mixture of … some of the songs were rebellious teenage anthems, and then some of them were not. She was such a good writer, and her melodies and her chord progressions were so strong. We were super-lucky to get her in. That was a big step. Then the next big step was actually a little bit later when we finally got our record deal and they brought Richard Gottehrer in. Richard had been a very successful songwriter in the 1960s. He had produced Blondie. So he really understood the whole ’60s vibe, and he pulled out more of that from us. He was definitely the one who said, “You guys have got to slow down.” We thought he was crazy. But now when I listen to those really, really old recordings of us, I just cannot believe how fast we were playing everything. [Laughs.] I don’t even know how my arm played that. But make no mistake, the songs are still really fast after we slowed them down.

You’ve stated that you believe songwriting is a really specific skill that many people don’t possess, and that “it’s a lot of extra hard work that other people aren’t doing.” What do you remember about writing songs for Beauty and the Beat, many of which you wrote with Charlotte?

One of the most amazing things was that we were both on our own writing paths. At that time I was writing a lot of lyrics, and Charlotte was writing a lot of music — I worked in basically what would now be called a sweatshop in downtown L.A. as a patternmaker. I distinctly remember my head was a million miles away from clothing during all those shifts. I was thinking about the band all the time, and I was writing lyrics on the actual patterns. I remember doing that because you made these paper patterns and that’s how they cut the fabric. I would come up with tons and tons of lyrics, and Charlotte would have tons and tons of musical ideas, and we would get together and very magically — and I’m not kidding — these pieces would just fit together. Like it was some kind of bizarre psychic connection.

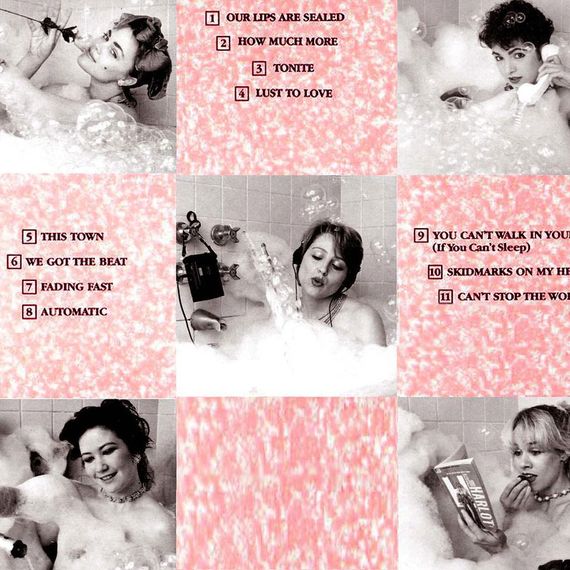

What’s the connective tissue, either lyrically or thematically, of the album’s 11 songs?

A lot of it is about life in Hollywood, and a lot of it is about being a young woman. Especially the song “Tonite,” which is totally about being in a girl gang — that feeling of compatriots and unity.

“Our Lips Are Sealed” is the most famous song you’ve written, but there are so many other great tracks you penned for the album. Do you feel there are some that are underrated or deserved to be singles?

I still believe it’s a really strong album with a ton of really great songs. I think we could have continued releasing singles, but we had this crazy notion that we didn’t want to milk our fans. So we absolutely forbade our record company from putting out any more singles, which is probably the dumbest thing a band has ever done.

Oh wow, what was your reasoning for that?

I think we still thought of ourselves as punk rockers. We were very empathetic with our audience, and we didn’t want to be seen as money-grubbers.

What gave you the impression that your audience felt that way?

There were a couple hundred people from the original scene that thought we were sellouts. And because at that time we gave a fuck what people thought of us, we were very hurt by that. So I think that entered into it. But I think that the Go-Go’s had a certain ethos and attitude in the punk scene that was like, “We’re all in this together. The fans are as important as the band.” We thought that continuing to release singles was sort of crass.

When did you stop giving a fuck?

About a year ago.

A year ago?

It has taken my whole life and a lot of work on myself to stop being such a people pleaser.

That’s a huge accomplishment to get there.

It is huge. I think a lot of women start to see that in their lives — the way we women say sorry, over and over and over, dozens of times a day in really inappropriate situations where you have nothing to be sorry about. It’s something that has nothing to do with you. And I think the whole people-pleasing mentality and the codependent thing is a really, really, really bad problem with women, especially women of my generation. A lot of us have not come around until we’re in our 40s or 50s or 60s.

If you could retroactively release a third single from Beauty and the Beat, what would you now choose?

Definitely “This Town.” I think “This Town” might be our best song. After all these years the lyrics are still fantastic and resonant, as is Charlotte’s guitar line. It’s just a great song. Besides that, I think “Skidmarks on My Heart” could have been a single, or possibly “Fading Fast.”

You all spent months in New York City recording the album. What do you look back on most fondly from that time in your life?

It would have to be living in the Wellington Hotel and what we would do after the studio time. That hotel was super-run down, but the rooms were huge. All the rooms were like suites. At the time it was pretty seedy, but it was close to everything. Oh my god, the antics we got up to. It was one of those buildings where there was a well in the middle so it was shaped, basically, like a square donut, so we used to chuck things out of our windows and into the windows across us. People would be like, “What the fuck.” Charlotte and I shared a room, and at that time she was super into Godiva chocolate. I remember us lying in bed and her eating Godiva. What’s funny is that on the cover of the album, she’s eating a Godiva chocolate. Belinda, Kathy, and I were constantly in search of boys. If somebody brought a boy home to their hotel room, we would drag a mattress into the hallway. [Laughs.] That was a signal not to come in.

I found it interesting that when you first heard the finished album, you hated it, because it made the Go-Go’s sound slower and more pop-ified. There was also that dichotomy of listening to your recordings outside of a studio. When did you come to the realization that your initial instincts were wrong and you had a smash record?

As far as us getting used to it being slower, that probably took us 20 years. I felt like my voice sounded like Minnie Mouse. As far as understanding that we had a big hit, it really wasn’t until we officially made it to No. 1. It’s pretty hard to deny that you’re a hit when you’re No. 1 on the charts. Funny enough, we were opening for the Police at the time we hit that milestone. They were great gentlemen about it. It was nice, because they could’ve been buttheads or kicked us off the tour. [Laughs.] They were very nice about it. But they were so popular that I don’t think they had anything to worry about.

When I interviewed Belinda prior to your official Rock Hall induction status, I asked her what the biggest revelation revisiting Beauty and the Beat was 40 years later, and without missing a beat she said, “I didn’t realize what an incredible album it was.” What are your big revelations?

We’re literally the first all-female band to get to the top of the charts that wrote their own songs and played their own instruments. That is our huge legacy. I like to think our other legacy is that we inspired other girls and young women to pick up an instrument and learn how to play it, because all of a sudden it was possible.