This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Jesse Armstrong has one of those faces that seem a wee bit anxious even if he’s just sitting quietly, eating breakfast. It’s been a complicated year for the creator, executive producer, and head writer of Succession. He closed out the fourth and final season of one of TV’s most-talked-about dramas on a high note, depicting the eponymous scramble to take over a media empire as a pack of wild dogs devouring itself, pitting sibling against sibling in the aftermath of the patriarch’s death and leaving those who felt most entitled to inherit the kingdom with almost none of what they’d dreamed of. Armstrong had been unable to talk about working on the series when Succession ended before the writers’ strike was resolved. But during a recent visit to New York, he was finally unleashed to discuss the misadventures of America’s favorite dysfunctional billionaire family and that final violent, near-fratricidal scene: “I went pretty crazy in the edit with that one, I remember.”

The story ends with none of the kids running the company and the most ambitious wannabe-CEO, Kendall Roy, thwarted and destroyed. Did you always know where you were going to end up?

I didn’t know where we would end! When the room was first assembled and we were doing the first season, our thought was, “Will we get another season?” But I did know, even from writing the pilot, what the tone of the ending would be. It’s not impossible that one of the kids could have emerged in some grubby way as the titular head of the company. But I knew there wouldn’t be a clean victory and it wouldn’t be a celebratory coronation, Star Wars style.

Gerri hanging a medal on Shiv!

Yeah, with Greg as Chewbacca roaring in pleasure!

Do you think there’s a way Kendall could have ended up getting what he wanted?

That’s the sort of proposition I would often raise in the writers’ room. Once a show is made, it feels like there were iron cages of possibility and rules that had to be followed to determine what happened. But it’s not like that.

How would you present or request alternative possibilities to the other writers?

I might come to the room and say, “Kendall seems to be offered the job in the very first episode. His dad in some ways does want him to take over, and in some ways, don’t we all feel he really would be the kind of guy who might take over? It doesn’t mean he’d be good at it. Let’s spend the day talking about what would happen if Logan died at a particular moment, or if he had the right friends around him. Could we make that happen? It would be interesting to see if it could happen.”

The writers’ room was a testing arena for the truth. Kendall taking over couldn’t happen because it just doesn’t feel true enough. If we wanted to make that happen, we would need a particular constellation of forces in the media, financial, political, and social worlds to make it happen. But we’d have been forcing it. And if we’re forcing it, why are we forcing it? We’re not trying to do anything other than be a good picture of reality, and to tell ourselves and other people how we think the world works.

That is a long-winded way of saying I don’t think he ever would take over. That’s just not how the show was constructed.

Is it right to say it’s Tom who inherits the kingdom?

To me, he feels like one of those emperors at the messy end of the Roman Empire when it’s like: Okay, he’s emperor, but there’s another one in Byzantium, and Oh no, there’s another one who’s popped up in Germany and you’ve gotta march the legions up there! You’ve had two years to build a triumphal arch, but suddenly the Visigoths are coming in. Tom’s not the emperor in the way that Logan was. He’s the titular emperor. He can put it on his résumé.

The progression of his character is so unexpected. He seems like a flunky at the start, but when Logan is dying on the plane, he’s more in control of himself and the room than he’s ever been. That was the first time in the show when I thought, Okay, he could actually be in charge.

There is a particular type of person who drifts upward by being amenable to power, and that’s what Tom is. Those people don’t always take over, but they sometimes do by being useful and making the fewest enemies rather than being wheel-to-the-dagger. You wait until after the assassination to take over and then hopefully you’re Octavius at the end of the civil war and everyone’s tired!

How did Matthew Macfadyen end up on the show?

That was one case where I did kind of know what I was doing. I’d always admired him. I’d seen him in a Trollope adaptation on the BBC being very funny, which is something that he’s — as we now know — great at. I was like, I’d love to write something where he gets to do that.

I get stray lines of his dialogue in my head sometimes. On the way over here I remembered his delivery of, “You don’t hear very much about syphilis anymore. The MySpace of STDs!”

Matthew is like some incredibly precise machine. “Can you calibrate it 3 percent in this direction?” and he goes and does just that rather perfectly and you’re like, “Oh no, maybe I was wrong; it needs to go 4 percent in the other direction.” He has that level of control.

How does the extraordinarily painful relationship between Tom and Shiv inform the arcs of those characters over time? Particularly in the corporate parts of the story?

A lot of stuff on the show we have models for — the internal workings of Disney or Shari Redstone and her brother and dad. Robert Maxwell’s family has lots of complicated relationships. This was more a creation of the show. I guess it’s the princess and the lowborn outsider; that’s a story shape we know from other places. How does it affect their trajectory? The more sophisticated Roys misapprehend Tom, right? They think he is no threat because he has, as someone says, “a bit of an agricultural walk.” He looks like he might be what he says he is, so they mistake that — and maybe Shiv does too.

When I did interviews in the first and second seasons, people often asked, “Why is Shiv with Tom? I like the relationship, but my friend said they don’t believe it.” It made sense to me. I’ve seen it quite a lot in life, where rather powerful women pair up with plausible, striking, solid, rather unthreatening men, guys who are gonna go to dinner with them and do the right thing and be charming.

And not resent the fact that their partner is the center of attention.

And be very happy to play that secondary role, yes. It’s a very particular kind of guy. But Tom also has a sort of old-fashioned machoness that quite fits the world. Shiv has grown up in a pretty aggressively male atmosphere, and she likes having Tom by her side. She has always had a lot of power, but he is the one who’s dreamt of being, in a Fitzgeraldian way, within this wealthy and charmed circle. The bit we brought to it as we developed the series is how wrong Shiv got him. This person’s ambition is burning bright. He’ll be pushed around a lot, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t have his own interests. And through a sort of egotistical arrogance that gets bred in those kinds of families, she forgets that Tom has his own interests.

When I watched key episodes and moments again, they landed differently. I found them to be more painful and sad, even in moments that aren’t “marquee” in a pivotal episode. When Logan dies, Roman can’t stop himself from telling Gerri they intend to fire her and tell the media it’s because she failed to manage the cruise-ship scandal. The first time, that exchange was horribly funny to me in a tossed-off, Veep sort of way. But Kieran Culkin’s expressions made it impossible to laugh this time. I felt I was seeing a person whose emotions are misfiring, like when you turn a key in a car’s ignition but it won’t turn over.

I think that’s dead right. We see the particular trap the kids fall into, the question of whether they should role-play their dad — who would see firing somebody as part of the rich tapestry of the gamified version of life — or whether they should let themselves feel what they actually feel. In that moment, Roman feels deeply compromised, sad, and bereft that he’s going to do something so violent to someone he’s had these complicated feelings about.

There’s also the scene where Shiv is intimidating a female witness to the scandal while pretending to be a good feminist. Of the three main siblings, she feels the most guilt for being horrible. But not enough, apparently.

I would reject any analysis where she was completely self-serving in that scene. Sarah was unbelievably brilliant in it because everything Shiv says that is self-serving is also actually true, right? If this woman does the right thing, she will get thoroughly destroyed as an individual, as we’ve seen in public life. Even though you’ve done something very culturally honorable and useful to the world, it can have terrible personal consequences. The fact that Shiv is telling the truth about that is what lets her sleep at night. I’m not sure she’d be able to do the version of that scene that is entirely duplicitous.

Shiv is so excluded and put-upon by the men in her family. When Logan dies, I was struck by how Kendall and Roman take her for granted. They’re trying to talk to their dying father on the phone, and it doesn’t occur to either of them to include their sister until it’s too late. Then they pressure her to go get Connor, whom they also failed to include.

The women writers in the room were particularly aware of how much emotional work often gets left to women in families. It’s part of the geometry of families that the practical arrangements and the emotional making-stuff-work part of it often falls to them. I will go a little easier on the brothers about not getting her on the phone immediately — it’s Connor they really fuck over! They literally don’t even think about him! Whereas Shiv, they get her as soon as I might remember to get a family member in such a situation. But they certainly do think of her as, Oh, something difficult and emotional needs to happen. Where’s Shiv to go and do it?

There’s also that little moment with Connor and Willa where he essentially says, “Are we going to cancel this wedding or not?” and they proceed to have a very honest, tough conversation. Maybe the only one they have on the series!

The show is a lot about lies and truth, right? There’s a lot of lying, a lot of obfuscation, deception, faking things, representing a set of facts in a certain way to your advantage. One of the tragedies of the family is how contingent and strategized all the relationships have become. It’s second nature to them to see things at six different levels at once: a financial level, a business-future level, a media level, a how-it-would-be-seen-by-people-on-the-outside level, and also how it would be seen by their father, and how it would be seen by their kids. They naturally “PR” themselves. Therefore, when you get moments of people telling us all the most cleaving versions of the truth — a truth that is not self-serving in any way, like Shiv in that other scene — when you’ve just got the truth, it hits. You go, “Oh right — there’s no reason for that person to say that, other than that is the truth.” And because it’s so rare on Succession, I really loved writing these moments.

I’m interested in what you say about the show feeling darker or sadder the second time. The thing I hear more often is, “When I watch it the first time, it’s anxiety to the floor. But then when I watch it again, it’s easier to enjoy the jokes.” But maybe with this last season, and knowing where it’s headed, the dark flavor comes through more?

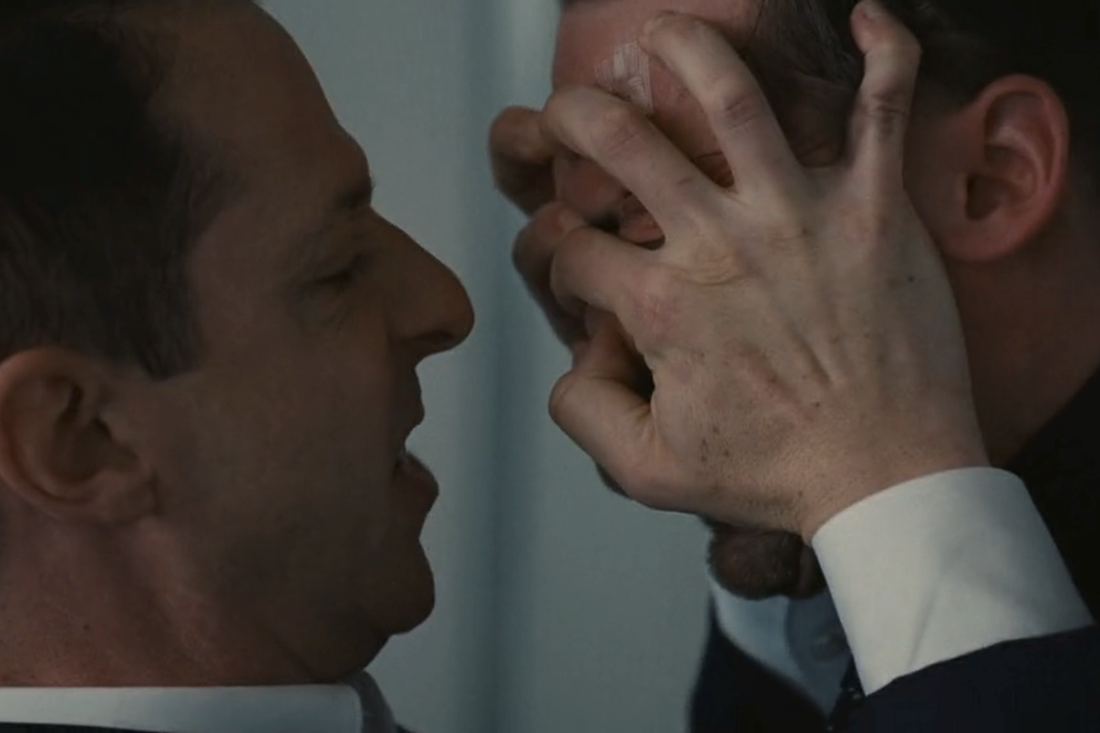

Well, it does culminate with a guy trying to blind his own brother!

I went pretty crazy in the edit with that one, I remember.

Were you ever concerned that confrontation was going to get physically out of hand?

No, because Jeremy was very controlled. We shot it right toward the end of the shoot — it might have been the penultimate day in New York — and it was very fraught. It felt brilliant on the day, watching it. Then in the edit, I had a terrifying feeling of, We haven’t captured what I felt watching on the monitors as they performed the scene. Mark Mylod was recutting it and Ken Eluto was recutting it and we had all these different versions and we were comparing them all to each other: “In 6A, you see a little more of that and a little less of that — how much pressure should be applied?” Lucy Prebble in the end said to me, “They’re all the same. It’s there. You’ve got it.” We were coming to the end of the show, and I think I was scared to let go.

In that moment late in the season when we see the video of Logan after he died, it seems as if Connor and his father are capable of genuine mutual warmth. I never saw that between Logan and the other children. Does that hint he loves his father in a different way than the others, or has a different relationship?

Yeah, it does. In TV shows, obviously, we don’t do the boring stuff — the meetings that are not incendiary or the family gatherings that are less combustible. But that video was a rare opportunity for us to present a scene where something incendiary didn’t happen.

Even though Connor gets condescended to, there’s an ease to his relationship with his dad that the others don’t enjoy. Maybe it’s because Connor is rather, in a touching way, resigned. He knows his dad doesn’t consider him to have any quotient of the right stuff, so he’s released from that. Which is sad, but maybe makes dinner easier!

Does Logan actually love his kids, or does he wish he did or think he does?

Brian Cox asked me that question early on and I said “yes.” That’s the headline answer. But then you get into a much more complicated set of questions. I think of Prince Charles’s answer “Whatever ‘in love’ means,” which is what he said when he was asked whether or not he loved Diana when they got engaged. I don’t think Logan would say “Whatever ‘love’ means.” He would say “Yes, I love them,” and it would be for other people to say, “But what does ‘love’ mean if you are able to dangle this prize so infuriatingly out of grasp and torture them with it?

I guess the tragedy — one of the tragedies — is that he’s a monarch, and he wants, like a pharaoh, to live on forever. One way to do that is have his lineage perpetuated, have the next person crowned, and therefore the name goes on. But as with corporate leaders — Bob Iger springs to mind — you identify the person, you give it to the person, you feel this sense of relief and transcendence that the project’s gonna go on, and you wake up in the morning, you’re Lear, and your power begins to seep away. The spotlight, the cultural heat, the political heat, the financial heat, goes to the successor. People don’t like it. They thought there was something innate about them which made them powerful, desirable, fascinating. As soon as they start to feel that diminish, they want it back, strongly, and the person who was symbolically the future and the beating of mortality becomes the very symbol of mortality. As soon as Logan anoints his children in different ways, they become incredibly unsatisfactory and viscerally upsetting.

Because they’re not him.

They’re as close as he’s gonna get, but they’re not fucking close enough, are they? You could make a very legitimate argument that he doesn’t love his kids, but you could also say he does.

The underlining versus the strike-through.

Exactly, yeah!

How did Brian Cox get the part of Logan?

When McKay and I first talked about it, his first idea was Brian. I was looking back at some old papers in my office, the sort of thing you do when the show’s over, and I remembered I’d seen him do Taming of the Shrew with the Royal Shakespeare Company when I was a schoolboy in Stratford in, like, 1987 or something. That was quite extraordinary to think about later, having such a close working relationship with him.

What parts of the character come from the actor?

Initially Logan was going to be Quebecois Canadian, but Brian comes from Dundee in Scotland, and Dundee has a relationship with journalism. D.C. Thompson was a big Scottish journalist with a family, so it felt like there was a richness to that backstory if we infused it with a bit of Brian that felt acceptable and not crossing a line in terms of taking things from a person’s life. Brian was comfortable with it, and those details made the backstory.

One of the things I noticed about a lot of powerful men is that they don’t speak that much. When they do speak, they often speak quietly or mumble, and people have to lean in and interpret and listen for the pauses on the phone call and guess what they mean. Power comes from people trying to constantly figure out what you are thinking or meaning. It was always clear that Logan was going to have fewer words than other people. And fortunately, there’s no one who’s so expressive in repose as Brian. He delivers the words amazingly — and it’s lovely to be able to give him a speech, which he always knocks out of the park — but it’s great to have somebody who could be that quiet and often-glowering presence, like this huge heavy anchor at the heart of the show.

With Brian and the other actors — I’m also thinking of Kieran — we had people who could do the words in a way which makes the characters reveal themselves. It’s like pouring water onto a scroll and revealing a text that’s hidden code. Kieran loves saying unsayable things, or doing something that should never be done. “Hey, hey motherfuckers, what’s up?” That’s his first line! As soon as we saw him do the character it was like, “Throw the other tapes on the fire.” There cannot be anyone better in the world at doing that part.

There’s something genuinely haunted about Roman. You see it in the eyes.

With Kendall, it’s, “You’re the first son, you’re going to be king, so you have this relationship to authority.” But if you’re the second son, what’s your relationship to power? It seems like a bit of a cosmic joke on you — it’s probably not going to be you unless someone dies, but as a result, it gives you a certain freedom of movement.

They can’t take it away from you if they were never going to give it to you in the first place?

The world becomes a bit of a joke. You become a bit of a joke. Everything becomes a bit of a joke.

Why did you wait so long to kill the king?

It was probably only for want of having a better idea. But also the more we did the show, the more I realized how brilliant Brian was and was more and more reluctant to do the show without him. Then again, it has always been called Succession. It was always going to be about what happened when the sun went out. I think we made the right choice in terms of how long you want to have that world exist.

Did you ever have The Godfather in your mind as you were working on this?

It kept coming up in different ways, in performance, in rhythms. We’re in the American arena, and The Godfather is the canonical version of American familial power and also of power in decay. When you have something that’s a real powerful cultural touchstone like that, whether you move toward it or against it, you’re still acting in relation to it.

How did you calibrate the ratio of comedy to drama in the series, both at the start and as it went through four seasons?

That’s a tough one to talk about. There was no version of Succession that was more funny or more tragic. The tone we settled on was just the tone which seemed amenable to me and a tone I was happy to write in. I pitched it somewhat tongue-in-cheek as “Festen Meets Dallas.” It was my hope that we might have something of a Celebration flavor to it, of peeking behind the curtain at the family event.

I hadn’t thought about the Dogme 95 film movement in relation to Succession! But now that you mention it, it seems obvious. The handheld camerawork — and the anxious, dread-filled tone, maybe?

It’s the single most important thing as a viewer of TV and film: tone. It’s ineffable. You can go to very surprising places for a show you’ve decided you’re onboard with if you love the tone. And if the tone is off, the thing just lies there, dead. But talking about tone is difficult for me. I can talk about casting and I can talk about how we construct stories and where they come from, but tone is very hard to intellectualize or explain. You can describe it after the fact, but it’s very difficult to say, “I would like to write something with this tone.” It has to just be there. I remember early in the shooting thinking, I don’t know if this show is going to be successful, but it is exactly what I hoped it would feel like.