This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

John Cameron Mitchell and I are driving through New Orleans, in a black VW Tiguan new enough to not yet have plates, to see the house that Joe Exotic bought. Not Joe himself, the exotic-animal zookeeper (a.k.a. Joseph Maldonado-Passage) made famous by Netflix’s opiate-of-the-pandemic docuseries Tiger King, who is currently serving time for attempted murder for hire in a federal penitentiary in North Carolina. But playing Joe Exotic in Peacock’s new scripted series Joe vs. Carole, which begins streaming March 3 and dramatizes Exotic’s zesty, beyond-a-reasonable-doubt criminal rivalry with fellow big-cat keeper Carole Baskin (Kate McKinnon), is what gave Mitchell the wherewithal to become a homeowner at the age of 58.

For 29 years, home for Mitchell has been a rent-stabilized West Village one-bedroom with a refrigerator tucked into a living-room corner and a copy of the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks … framed on a wall. (On a recent visit, they were joined by one of Exotic’s costume nipple rings sitting on a side table.) The story of his career, like so many others in New York, is a real-estate story: The apartment deal Mitchell got, and held on to, helped him go from being a stage actor to a downtown queer impresario who never really had to sell out.

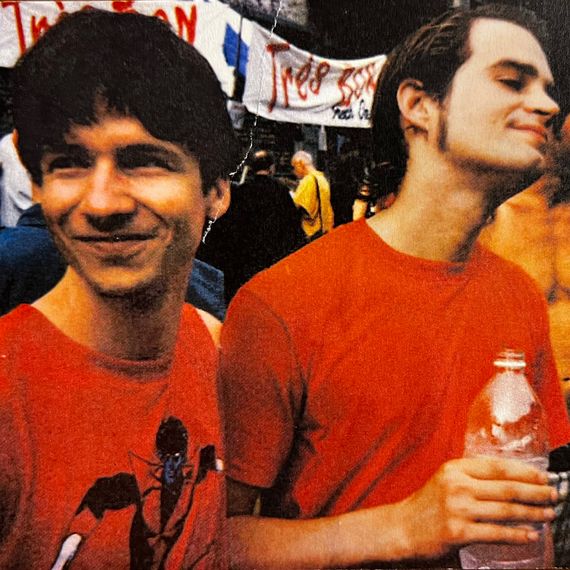

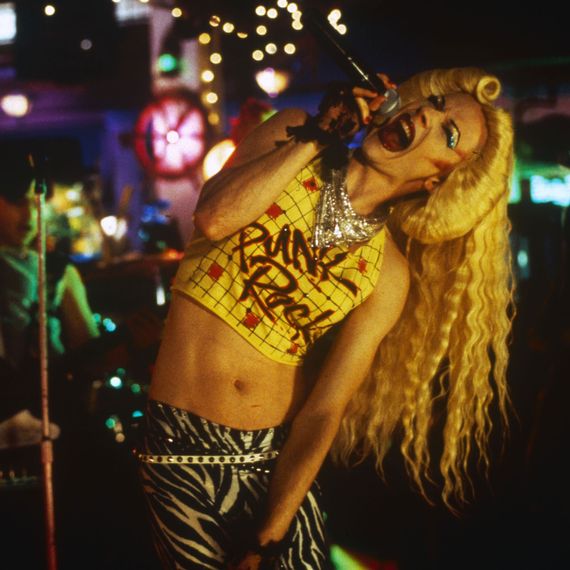

Since Mitchell broke through with Hedwig and the Angry Inch, a glam-rock drag musical he wrote with his friend Stephen Trask — and starred in, first onstage, then onscreen — he has flirted with mainstream audiences and the industry suits who court them, then plunged into some of the least marketable projects imaginable. After directing himself in the film version of Hedwig, to critical if not commercial success, he conceived Shortbus, a film about post-9/11 anomie in New York featuring actual, unsimulated sex, which was, on its face, nearly unfundable — until he got it made and cheered at Cannes.

In recent years, he has sustained himself as a character actor, a reliable source of slightly sour comic relief on TV shows including Girls, Shrill, and The Good Fight. “Acting is what pays the bills,” he says. “All the other stuff is too experimental or unusual” — collaborative albums, a narrative podcast featuring a singing brain tumor — “to actually make a living.”

With Joe Exotic, Mitchell has his first leading role since Hedwig and, he tells me, his favorite role on film ever. Joe is a choice morsel for any scene-chewing actor: vulgar, fabulous, chronically dishonest, credibly murderous, a self-mortifying sinner-saint in pink sequins, irresistible grist for Hollywood’s reboot mill. Unsurprisingly, several big names expressed interest, and several projects were undertaken. Nicolas Cage was attached to a competing Joe Exotic project for Amazon, since shelved, and Rob Lowe may still be working on one with Ryan Murphy. But it’s Mitchell who will be the first Joe Exotic since Joe Exotic.

Unusually for a seasoned actor, he auditioned, and the casting came through quickly enough that he suspected he hadn’t been first choice. But Etan Frankel, Joe vs. Carole’s showrunner, said he can’t imagine anybody better. “It was difficult to find the right person to play this part,” Frankel said. “It’s a tricky part to play because you have to find an actor who is able to tap into the charisma and theatricality of Joe Exotic while being able to get at the more human moments of the man.”

“I lived in places he did, so I kind of knew the environment,” Mitchell says. “I love Joe Exotic, even though I don’t condone his behavior.” He had watched and then stopped watching the Netflix series: too rubberneck-y, too little empathy. “Look how crazy these people are, we don’t particularly care about them, let’s all feel better than them,” he says. “I mean, he was an attempted murderer. But I tried to do right by him in the portrayal so he’s not a monster.”

On a visit to New Orleans in 2020, Mitchell was helping a friend look for a house when he decided to look for one too. New York used to be more hospitable to the kind of durably undomesticated, reliably provocative, comfortable-on-the-margins artist who, like Mitchell, kept his overhead low. “He’ll never give up his apartment,” his friend Paul Dawson told me. “It has been very important to him throughout his career and continues to be.”

But the city changed around him. “New York just became too expensive to be casual,” Mitchell says. Hedwig opened at a small theater in the tumbledown Riverview Hotel on Jane Street in 1998, the same year Sex and the City premiered on HBO, but the future of the neighborhood belonged to the brunch spots, not the flophouses. In the years since, the Riverview has become the Jane, bought and gussied up by Sean MacPherson and Eric Goode to become sister ship to their Bowery Hotel, and the theater became a taxidermy-filled nightclub. Soon it will become even more elite, as the New York outpost of the industry-centric L.A. private club San Vicente Bungalows. The old libertine freedoms of art and life and the parties where they intersected are less in evidence.

In the past several years, a parade of friends and acquaintances from New York and L.A., avant-garde snowbirds, had been moving to New Orleans, and its permissive witchiness appealed to Mitchell. “It feels a little bit like New York was in the ’80s and ’90s,” he says. “In terms of ‘Make things happen,’ you know? The art is made of whatever you picked up at the dump.”

With his modest Joe windfall, he bought a house, formerly owned by an occultist church in the Aleister Crowley tradition: a little off, a little unloved, maybe a little haunted, with a big ballroom, Greek inscriptions painted on the wall, and a ceiling sprayed with what appeared to be — hopefully — chicken blood.

The nearby houses in Bywater, painted Necco Wafer shades of green, purple, and blue, are mostly single-story stand-alones, but Mitchell’s stands out and stands above: peachy yellow with orange and blue trim, double tall, and windows as high as most of its neighbors’ doors. Bywater is in the Ninth Ward but close enough to the higher-ground banks of the Mississippi that its flood risk is relatively low, and the neighborhood feels arty and boho. Mitchell closed on the property last summer — according to city records, he purchased the place for an apropos $666,000 — and set about sanctifying it with his own icons, commissioning stained-glass portraits of Gena Rowlands, the gospel singer Mavis Staples, and his flexible friend Dawson as he appears at the opening of Shortbus, bent double and ejaculating into his own mouth.

“I’m making my little fantasy house,” Mitchell tells me, “taking that energy and mixing it with other energy and moving in a different direction. And it feels very right.” Not so much run out of town — the New York apartment stays — but seeking greener pastures elsewhere, freer movement, different spells.

Mitchell was born in 1963 in El Paso, Texas, to John Henderson Mitchell, an Army man (eventually a major general), and Joan Cameron Mitchell. The Mitchells had five sons, one of whom died in childbirth and another, at 4, of a heart defect. His mother lost herself in grief and Catholic devotion. “She wasn’t much of a mom,” Mitchell says. “She wasn’t really there for us. She was kind of running after the Virgin Mary.” She would tell Mitchell he should become a priest.

When he was growing up, the family moved often. “I always had a little bit of an on-the-lam feeling,” he says. “I always thought I’d be a good hostage. I’d know what to do.” Many of his biographical details are refracted through Hedwig and the Angry Inch: The Mitchells also lived in Berlin at the end of the Cold War and on an Army base in Junction City, Kansas. Hedwig is based in part on Helga, his brother’s German babysitter who turned tricks on the side.

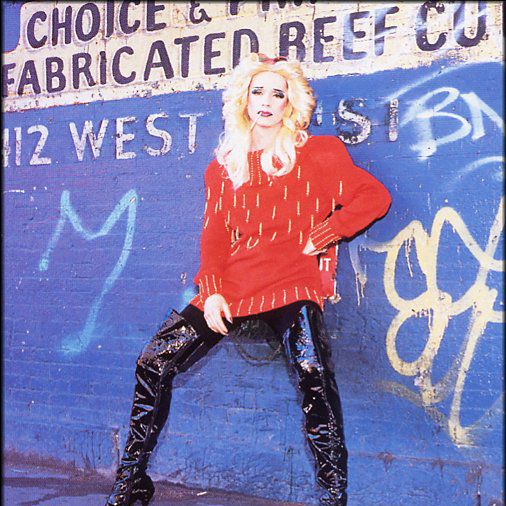

Mitchell moved to New York in 1985 after studying theater at (though not quite graduating from) Northwestern University. Very quickly, he began booking parts on Broadway: understudying Huck Finn in Big River, playing Dickon in The Secret Garden. He might have had a polite, unexceptional theater career — he racked up respectable Drama Desk nominations — had he not begun developing the character of Hedwig with Trask at Squeezebox, a gay party in Siberian western Soho that mixed drag queens with rock and roll. (Trask and his band, Cheater, were the party’s house band.) Mitchell loved glam rock and musicals — his first album had been Elton John’s Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy, and he revered David Bowie — as did Trask, who, when they met in 1990, had recently changed his name from Stephen Schwartz to avoid confusion with the Godspell composer.

The two eventually worked Hedwig into Hedwig and the Angry Inch, with a book by Mitchell and songs by Trask. The show was a little lofty — based in part on Plato’s theory of love — and celebrated the fundamental squishiness of gender and the transformative power of drag (as Hedwig sings in what is arguably the show’s most rousing number, “Wig in a Box,” “I put on some makeup / Turn up the eight-track / I’m pulling the wig down from the shelf / Suddenly I’m this punk-rock star of stage and screen”). But the show is also unsettling and a little brutal. The Angry Inch, in addition to being Hedwig’s backing band, is what remains of her penis after an operation she undergoes at the behest of her GI lover and her mother to allow the former Hansel to leave Germany as Hedwig, an American bride.

Hedwig was heady, hard-to-pigeonhole stuff, and most theaters turned it down. But when Mitchell and Trask were able to put it up at the Jane Street Theatre at the Riverview in 1998, it was a sensation. It sold out night after night; celebrities came, including Ziggy Stardust himself. (“John, you got it right,” Bowie told him.)

Squirming in my seat at 14 that year, I was one of the many radicalized by Mitchell’s yowling, high-kicking portrayal of the glam-rock “internationally ignored song stylist.” That was the same year the also pathbreaking but sanitized Will & Grace premiered. (Drag Race was still a decade in the future.) Listening to Hedwig long for her lost other half — a plaint, rare in those days, for boys who suspected they had a little bit of girl in them or vice versa — in platform boots and a Farrah Fawcett wig in a banged-up ballroom near the West Side Highway was a queer awakening: Not quite “It gets better,” but at least “It’s here.” The 2001 film seems to have had that effect for millennials and beyond.

Over the years, Hedwig’s cult has spawned superfan Hedheads, countless tattoos, and, for Mitchell himself, more than one stalker. “It’s all ‘the freaks and the losers,’ you know,” Mitchell’s friend Amber Martin, a singer (and fellow part-time New York–to–New Orleans transplant) who now tours with him across the country for concert performances of the soundtrack, told me fondly. (“Midnight Radio,” Hedwig’s 11 o’clock number, ends with a loving and communing tribute to all “the misfits and the losers.”) “They feel like they’re seen.”

Hedwig’s success brought credibility and cultural capital — after the film, Mitchell says, there was “a metaphorical blowjob” from Harvey Weinstein and offers to direct Rent and Memoirs of a Geisha — but in a move he would repeat throughout his career, Mitchell used it for a quixotic dream project that was literally inadmissible to the mainstream: Shortbus. Dawson remembered Mitchell warning his actors that “we would probably be facing some kind of resistance and possible backlash. I don’t remember him expressing much reservation about his own career — he was so confident that was what he wanted to do. I know he had other opportunities that would have been far more safe.” When it opened at Cannes, recalled Howard Gertler, one of its producers, all the industry execs who had declined to fund it told him, “We still can’t release this movie — but we love it.”

It’s hard not to see some of Mitchell’s work, with its insistence on a broader, more humanistic spirituality, as a reaction to his inflexible upbringing. His strict and ostensibly all-American father, he says, confided in him late in life that he too was attracted to men but became “heterosexually competent” after meeting Mitchell’s mother, and that was that. Both parents were eventually supportive of their son’s work, after their fashion, but it’s hard to imagine it didn’t sometimes vex them. When they eventually settled in Colorado Springs, the local paper sent a reporter every time one of Mitchell’s achievements seemed suitably impious. When the Hedwig film came to Colorado, the Gazette noted the “tangled mix of pride and discomfort” the retired Mitchells felt; though “amazed and impressed,” “I have to say that I’m more a Guys & Dolls type of theatergoer,” John Mitchell said. After Shortbus, there was another news-gathering visit. “We call it the film that mother will never see,” Joan Mitchell told the paper.

A winding career followed. Mitchell directed Nicole Kidman to one of her many Oscar nominations in 2010’s Rabbit Hole (he also directed her to crickets in 2017’s How to Talk to Girls at Parties). He took 12 years off from acting — aside from a cameo as a Shortbus “sextra” — until he was lured back by a text from Lena Dunham about a part on Girls. “If he had been absent from acting, you sure couldn’t feel it,” Dunham wrote in an email. “He is the most surprising, inventive performer (and person) and truly represents what remains of eccentric and intellectual New York.” (He also doesn’t appear to age, she added, “which is rude.”)

Even Hedwig, which continues to be performed on professional and amateur stages around the world, doesn’t bring in enough in royalties to support him. “We’ve been doing this together since 1994 in some way or another,” Trask told me, and even so, “it’s not successful enough for us to hate each other.” Trask also left New York, in 2004. Today, he lives in Kentucky with his husband and works primarily on film scores.

Shivving propriety has always been part of Mitchell’s act. There’s a joke he likes to tell onstage as Hedwig: “I lost an uncle at Auschwitz,” it goes. “Granted, he fell out of a guard tower. We all suffered, ladies and gentle — what? Why are you yelling at me?”

He told it to me — twice — over the course of several weeks of interviews. And, okay, I laughed. But these days, this type of outré free speech can take on a bit of a trollish cast, and there is more yelling than there used to be. Mitchell has lately been on a retrospective victory lap, touring with “The Origin of Love,” in which he again dons the Hedwig wig for an evening of songs from the show and stories from its creation, and shepherding Shortbus through a theatrical rerelease. Both offer the opportunity to dissect past work with the present’s scalpel. The reconsiderations are not all in Mitchell’s favor. Hedwig and Shortbus were spicy in their day — Dawson told me he essentially never worked as an actor again — but a new generation is receiving them more spicily still.

In 2020, trans activists complained to the producers of an Australian production of Hedwig that featured a cisgender actor in the role. Mitchell and Trask, both of whom now identify as nonbinary, supported the production, noting that Hedwig is not trans per se, but the campaign was successful, and the production was derailed. It’s worth noting that nonbinary and trans actors, as well as cis men and women, have all played Hedwig; the trans performer Lisa Stephen Friday was scheduled to play the part in a D.C. production until the pandemic shut it down. There have been Black Hedwigs and Black Yitzhaks, Hedwig’s onstage foil, too. Trask noted that “the evolving way that we understand trans or nonbinary or gender nonconforming — it’s a pretty fast-moving train.”

At Q&As and talk-backs following the recent round of Shortbus screenings, Mitchell has found himself taken to task by those who don’t see themselves represented or who interpret the onscreen sex as exploitative rather than freeing. “The same night that someone said, ‘Is it your right to talk about an Asian woman having an orgasm?’ — a central plot point of the movie — someone else said, ‘Have you thought of remaking Hedwig with a more diverse cast?’ ” Mitchell says. “It’s impossible to discuss this stuff.” There are still those who revere Mitchell and his work, but the criticism clearly prickles him. “A lot of young people are kind of annoying to me right now,” he tells me. “A little naggy, telling you what you can and can’t do. Sometimes, you know, for good reason, but it does make me feel weirdly old.”

There are now a couple of generations that came of age watching Hedwig and Shortbus and mining them for possibilities. Riverdale did a full Hedwig episode; the Bushwick queer club 3 Dollar Bill is hosting “HED!,” a tribute to the show, in March.

For Mitchell’s devotees, the censoriousness is puzzling. Javier Calvo, one half of Los Javis, the Spanish writing-directing duo behind last year’s hit series Veneno, bought a DVD of Hedwig on eBay as a teenager and was “completely blown away,” he said via email. “Everything about it was life-changing for me.” It was a major reference point for La Llamada, the musical he made with Javier Ambrossi, which, like Hedwig, grew into a feature film. They described Mitchell, whom they eventually met and befriended, as their “gay guru.” The comedian and writer Joel Kim Booster, who played Mitchell’s husband on Shrill, also called him a major influence. He found Shortbus in college while working at a summer theater where it was one of only two DVDs on hand (the other was Wet Hot American Summer). “Those two movies shaped me and my sensibility more than anything else I can remember,” Booster told me. “I didn’t know you could do things like this.” He came back to school and changed his major from musical theater to playwriting. Fire Island, his debut feature, comes out this June.

And yet when he tweeted about Shortbus recently, Booster recalled, “I had a few people, like, slide into my DMs and be like, ‘You know, that movie is not okay.’ Agency, I think, is the big buzzword that slips in when I have conversations with people who think Shortbus is not something we should be celebrating anymore. It’s not a criticism that I really agree with, quite honestly. I just think it’s interesting to hear people really not be able to articulate necessarily what makes the movie wrong.”

“Somebody had said during a Q&A, ‘Who are you to tell the Asian woman’s story?’ with the assumption that that’s not my story,” said Sook-Yin Lee, who overcame the objections of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, her employer at the time, to play Sofia, one of the main characters. “I created the character. That is my story.”

In some ways, the culture has finally caught up with Mitchell. “Hedwig would never, couldn’t have been on Broadway back then,” he says. At the outset, even New York’s more independent-minded downtown theaters, like New York Theatre Workshop and the Public, turned it down, he says. By 2014, that was no longer true: That year, Hedwig opened on Broadway to acclaim, winning Tonys for Neil Patrick Harris (as Hedwig) and Lena Hall (as Yitzhak). Mitchell, who did a few performances — older, wiser, and occasionally in a knee brace after injuring himself doing the choreography — won a special Tony for it the following year. In 2019, the film version, which never recouped its $6 million budget, was enshrined in the Criterion Collection.

But in other ways, as the diversity complaints and sensitivity checks make clear, the culture has moved past Mitchell. Recent roles have cast him as a gay contrarian: art typecasting life. On Shrill, he plays a character based on Dan Savage, needling the plus-size protagonist about the obesity epidemic; on The Good Fight, he’s an elder, but no less morally stunted, version of Milo Yiannopoulos, the right-wing gay troll. In 2019, he went on the dirtbag-left podcast Chapo Trap House. “You’ve avoided being called out in the way that Dan Savage has been called out or RuPaul has been called out,” noted one of the hosts. “I’m sure there will be some point — maybe it’s something in this podcast — that will offend,” Mitchell replied.

“I come out of Borscht Belt humor; I come out of queer humor, drag; I come out of rock and roll; and I come from Broadway,” he says. “All of those tools are really useful for making art but also for making protest art. And nowadays, a lot of those tools are considered a little bit déclassé or old-fashioned or perhaps even uncool.” He acknowledges that the new sensitivity came in many cases as a necessary corrective, even while admitting that “the oppression Olympics can get on my nerves”: “I want to remind people that it is how you say it, not what you say. You know, you can call someone a ‘faggot.’ I don’t believe in canceling the F-word. I don’t believe in canceling the N-word.” Whether the criticisms of him are entirely in good faith, whether they’re reasonable, is open to debate. What isn’t is that the debate is no longer on his terms.

Mitchell isn’t nostalgic, exactly, but he has grown a bit cranky at being expected to watch what he says. Cranky, but also careful. (He says he loves telling ethnic jokes because he could be canceled, though he figures he’s too old to be, yet he makes it very clear he doesn’t consider himself a victim of his increasingly insistent critics.) “We’re in Wokeland now, so everyone’s on notice,” he says. “There is a bit of a cultural revolution. The kids-have-guns cult.” He dreams of a more peaceful revolution, an incremental revolution. He has been steeping himself in the anarchism of thinkers like Murray Bookchin, the Trotskyite libertarian socialist; he describes himself as a “radical, incremental, anarchist centrist.” New York, Mitchell says, can be “a little constricting.”

Thus New Orleans. The vibe is a little bit looser down here; there’s still “midget policing,” as he puts it, “but it melts more here. It’s hot.” Friends have been coming down and collaborators — all week, he has been working with Michael Cavadias, another veteran of the alt-drag scene, on what will be a podcast, a medium that appeals for its lower budgets and lower barriers to entry. Mitchell’s most recent undertaking was Anthem: Homunculus, a narrative podcast that was a spiritual successor to Hedwig, with music by Bryan Weller and an all-star cast that included Glenn Close, Patti LuPone, and Cynthia Erivo (you can also hear him sing on his brother Colin’s just-dropped podcast for kids, The Laundronauts.) “If I never make another film, that wouldn’t kill me,” Mitchell says. “People aren’t watching them, and they aren’t financing them. Shortbus I really could not make today for various reasons, distribution as well as wokeness.” Meanwhile, to pay the bills, he’s still acting. After Joe vs. Carole, there’s Netflix’s The Sandman, in which he plays a drag-club owner with a penchant for Gypsy. More, he hopes, will follow. After any given success, he knows “you get a couple of weeks of heat, which is irrational exuberance,” he says. “And then it goes away.”

That’s why, in part, he likes making his own creative communities with himself as the mother and father figure. He did it through all his time in New York — Shortbus was named after an underground dance party he threw, and since 2008, he has thrown Mattachine, a monthly party aimed at bringing that same spirit to New York’s oldest gay bar, Julius’ in the Village, which had gone to seed and hustlerdom but he and his friends helped to revive. And he hopes to do it again in New Orleans, staging shows in his bloody ballroom, engaging with his fellow artists, connecting. All his work, from Hedwig to Shortbus to Anthem, is obsessed with the possibility of forging connection and finding community. Even Joe Exotic, head of a harem of husbands and a cabal of like-minded zookeepers, arguably fits the pattern.

Here in New Orleans, Mitchell has spent the mild February afternoon driving around with Mitchell Kulkin, a friend from the Radical Faeries whom he persuaded to be his decorator, angling for a dining table and chairs for his new house from the cavernous warehouse furniture dealers and consignment shops (his New York place never had room for any such thing). “Visiting?” person after person asks as he browses giant burled armoires, conspicuous in an ankle-length checkerboard skirt and a rainbow-trimmed hoodie. “No,” Mitchell says cheerfully. “I live here now.” He is joining a loose community that is coalescing. Jason Sellards — a.k.a. Jake Shears of the Scissor Sisters — lives nearby. The lesbian burlesque duo Kitten N’ Lou are opening a sno-ball shop around the corner. Mitchell spent part of the afternoon texting with the singer Rickie Lee Jones, trying to persuade her to come to a screening that night (she demurred: Too much sex in Shortbus).

Before that, there was a visit with Lorraine Kirke, a new friend and fellow transplant (and mother of Jemima, Lola, and Domino). Kirke’s house, painted black and stuffed with battered finery, manifests a dusty bayou elegance that Mitchell appreciates, and she had offered to escort him to a local furniture shop to make an introduction. Before leaving, she gave him a copy of the coffee-table book she created on her “unapologetic interiors,” reading aloud a quote from Jemima, whose paintings hang on the walls: “She makes damaged goods feel at home.” “I mean, I do do a good brothel,” Kirke said as Mitchell and Kulkin enthused over her velvet couches, the front bedroom with a bathtub parked nearby.

“I bought this house about four years ago, and I just love it,” Kirke explained as we motored along to the shop. “We lived in the West Village. I really thought when I was in New York that I would never leave; there was no other place like it.” But then, she went on, “you just get to a point with New York, and it’s like …”

“Enough,” Mitchell said.

She turned to him. “Are there ghosts in your house?” she asked.

No known ghosts (and, by the end of the day, still no dining table), though Mitchell’s life has been pocked by loss, one of the many inevitabilities of getting older. He spent most of the pandemic working and still looks preternaturally, nearly Faustianly, youthful, but loss has trailed him all the same. “I’ve lost a lot of people in the last two years,” he says, including his mother, Joan, of complications from Alzheimer’s disease in 2020 (his father died of the same cause seven years earlier); the Hedwig concert tour “Origin of Love” was undertaken, in part, to pay for his mother’s care. Through the Alzheimer’s, Mitchell and his mother found a relationship they had never had. “She looked at me in the last couple of years once and said, ‘You’re just a boy,’ ” he recalls. Casting a shadow still is the death of his most serious boyfriend, Jack Steeb, who had played bass in Cheater and in Hedwig’s backing band and died of his addictions in 2004. Mitchell still refers to him as “my boyfriend.”

Mitchell says he isn’t seeing anyone seriously now. “I’m picky because I’m older. You know, I’ve had my heart broken, so I’m not leaping. I’ll have sex once in a while, but, you know, dating is scary. Because I’ve lived long enough, and I also like things the way I like them. I don’t like the idea of being responsible for somebody else’s happiness. I’d like to be happy together. Moving out of town might actually be good for this,” he muses. “People have more patience in the smaller towns. Not rushing to the next thing.”

As the car speeds back toward home with Kulkin in the driver’s seat, Mitchell pulls on a joint from his backpack and turns contemplative. We’re on our way home to get ready for the evening’s screening of Shortbus, the Q&A to follow, and the DJ set he and Amber Martin will do in the movie theater’s on-site bar for a crew of local devotees — an odd bit of New York–iana (one attendee will remove their shoes and begin performing a sort of karate-inflected voguing) extracted from its place of origin and set, a little incongruously, in a glowing New Orleans shopping mall. One other ghost troubles him a little, one not yet gone but fighting cancer in a federal medical facility in North Carolina. “I do feel a little guilty that I have a house because of Joe, and he’s in jail,” Mitchell says.

“Send him a card!” Kulkin suggests brightly. “ ‘Thanks, Joe.’ ”