It’s difficult to remember now how precious the blues seemed to rockers in the 1960s. The blues were a serious matter, meant to be played a certain way. Rock bands always fooled around with doing the blues louder and with less finesse, of course, but beyond that, folks like Eric Clapton were the models, with their sincere embarkations into the music. They were done with brio, but with probity and respect, too.

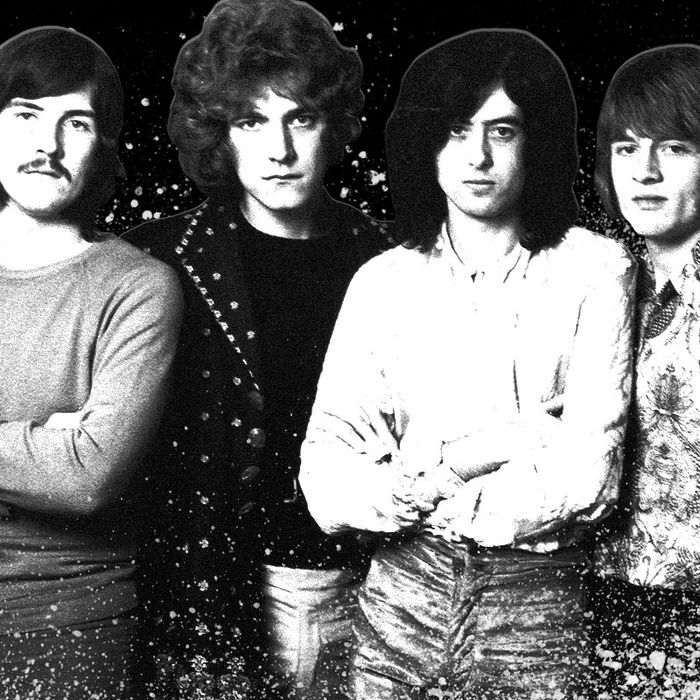

Jimmy Page put an end to all of that with Led Zeppelin, the band that broke the blues and created something new — hard rock, heavy metal, whatever you want to call it.

We blink — and many years have passed; five decades, in fact. This week, the band’s 1973 album Houses of the Holy turns 50. To celebrate, we’re re-running our original 2015 ranking of all of the band’s original studio work. But first, a little background:

Rock’s lumpenproletariat liked them a lot, and even those with finer sensibilities could not help respecting the band’s sonics, not to mention Page’s venturesome guitar chops. But the rock Establishment didn’t quite get the band at the time. All the old terms used to explain this still apply: Zeppelin were a sledgehammer, a steamroller, a juggernaut, a leviathan, picking the music up, turning it into a club, and wielding it unmercifully, often on innocent bystanders and any nearby baby seals.

Robert Plant’s lyrics — an amalgam of stolen blues lyrics, random and confused references to Norse and Tolkien mythologies, sullen misogyny, and utter nonsense — didn’t help matters. Still, something big was going on, and many people at the time didn’t get it. (Rolling Stone’s critical history with the band was particularly — indeed, uniformly — clueless.) A lot of this had to do with not seeing the forest for the trees.

The forest, in this analogy, was Jimmy Page.

Page was a prodigy of a new mold, a young man on the British blues scene who quickly became a coveted session player in the British pop factories of the time. There are enough conflicting accounts of the songs he’s played on to doubt some, but Page himself has said, for example, that that is not him on the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me,” but he is on the Who’s “Can’t Explain.” There was also work on a crazily diverse set of sessions: Van Morrison’s Them and Donovan, Tom Jones and Burt Bacharach, all the way to the blandest Muzak. He was then the final guitarist in the Yardbirds, a seminal British blues outfit whose previous guitarists were Jeff Beck and Clapton.

Page ultimately disbanded that group and began to experiment with what he called the New Yardbirds, which later became Led Zeppelin, filled with members he handpicked. There was an experienced multi-instrumentalist he’d met doing sessions, John Paul Jones. To sing, he found a striking howler from the Black Country, Robert Plant. Plant brought along an old musical friend, a primitive drummer, almost Cro-Magnon artistically and socially, John Bonham.

The first side of the band’s first self-titled album contained arguably the hardest-rocking, most thoroughly enjoyable set of songs any mortals had yet created. It created a sensation, and the group’s earliest tours began to spread the word of a uniquely powerful live assault. Zeppelin soon became the ultimate uncompromising hard-rock band, imperiously traveling the globe to deliver pummeling concerts at ear-splitting volume, attend to the local womenfolk, and take away unprecedented paychecks — this last one with the help of the band’s canny manager, a baleful beast named Peter Grant.

Zep was not a psychedelic band per se, but they recorded several of the great psychedelic mélanges of sound, in songs like “Whole Lotta Love” and “Dazed and Confused.” Zep weren’t a singles band — they complained whenever Atlantic would issue a single — but they had radio hit after radio hit. The band didn’t lumber like Sabbath; they weren’t effete, like Yes; pretentious, like ELP; or annoyingly intellectual, like the Who. Yet they weren’t even entirely stupid, like Grand Funk, or Foghat, or Uriah Heep, or Mountain, or take your pick of the innumerable doltish bands of the era. They just rocked. (See the entry on “Stairway to Heaven” below for more on this point.)

With only one exception, each album was arguably a surprise and an advance. Their fourth release, which was untitled but is sometimes referred to as IV (or “Zoso,” after a nonce faux rune on the sleeve), included the song “Stairway to Heaven.” It was not released as a single (unheard of at the time). That became first an unexpected radio hit, then the band’s defining song, and then, unaccountably, one of the most celebrated recorded tracks of the 20th century.

At that point Zep became something weird; possibly the biggest band in the world, and yet lacking the lyrical substance or aesthetic genius of competition like the Stones, the Beatles, the Who, or Dylan. Led Zeppelin played rock without any socially redeeming value, and they didn’t care who knew.

How did they get away with it? It’s easy but reductive to say it was all Page. He did become a master at producing awe-inspiring sounds, both from his guitar and the studio. An acclaimed guitarist, he is probably also the most underrated producer in the history of the music. Simply put, he added a dimension to the sound of hard rock. If Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” was the epitome of the genre at the time, Zeppelin was “Sunshine” squared. Page mastered the soft-loud song construction. He could make the band sound brutal and overwhelming, dry and brittle, warm and fuzzy, dark and folky, often over the course of a single song.

But Zeppelin’s secret is that the band had one of the most intensive casts of talent in the music’s history. Besides holding down bass as part of one of the most powerful rhythm sections ever, John Paul Jones could play anything. He’d taught himself to arrange and orchestrate while doing sessions, and brought a musical depth few other rock groups of the time had. Plant’s voice, which, yes, could run to the porcine squeal, was for the most part an instrument of truly awesome power. Paul McCartney was adorable and Mick Jagger oozed sexuality, true; but Plant was possibly the first rock front man who really did look larger than life. (Somewhat self-conscious of his middle-class background, he was called “Percy” behind his back by other member’s of the group’s operation.) As for Bonham, he was indeed, as the journalist and musician Mick Farren put it, “Loathsome.” Ferren went on to describe Bonham as “Keith Moon with all of the dynamite and none of the charm.” But that’s like saying, “He’s got all of Yo-Yo Ma’s technique but none of his gardening skills.”

These facets of the band balanced it out and gave them enormous tensile strength in every conceivable way. Plant and Bonham were from the rural Midlands, a major difference from London pros like Page and Jones. But Jones and Bonham had the natural affinity that rhythm sections have — and Page and Plant, the flamboyant front men, were friends who would travel together and write songs. Manager Grant created a protective sphere around the group; combined with Page’s propensity to paranoia, this helped keep the band close together with something of a siege mentality.

And finally, they had the luck to exist at a crucial turning point for rock. The supergroup Cream had disbanded, leaving a vacuum. Jeff Beck, who was working with Rod Stewart and might have put a similarly powerful aggregation together, took a pass. The focus of rock, in the wake of Sgt. Pepper, was just beginning to move from singles to albums. Grant, the band’s manager, sensed correctly that there was an untapped desire for a band like Zeppelin in North America, and devised a canny strategy to keep the band off TV and out of the singles racks, to force fans to see them live or buy their albums.

All of those factors together created the juggernaut that was Led Zeppelin. Led Zeppelin released eight studio albums, totaling nine discs, plus one extra single B-side, in a career of just a decade or so. There was also a two-record live set, The Song Remains the Same, and an accompanying movie. Neither are celebrated, but it must be said that parts of the movie show a band of extraordinary power; these days, blistering footage of the group is all over You Tube. After the death of drummer Bonham, Zeppelin disbanded, leaving only a motley collection of outtakes, called Coda, in its wake. Since then, the band have tended respectfully to its legacy; it’s very rare to hear a Zeppelin song in a commercial. The estranged Page and Plant reunited, Spinal Tap style, in the 1990s, and released a couple of albums as a duo and even toured, to no little hype at the time, but Page, particularly, betrayed the signs of extended drug use, and their collaboration during this period produced no notable new songs. It was quickly forgotten. Plant’s otherwise had a fairly decent solo career — and made Raising Sand, an acclaimed duet album with Alison Krauss in 2007. Page’s work has been haphazard and disappointing, like a bizarre 2000 live set he recorded with the Black Crowes.

What follows is my list of the band’s songs, ranked from worst to best. The criteria? I hope the reasoning speaks for itself. The on-record result — the sounds, the playing, the meanings — are really what matters, though the historical importance of a few tracks counts as well. Some adjustments are made as we go along, as you will see.

The list below sticks to the work the group recorded as a complete unit. Please let me know in the comments if I made any mistakes. Coda is left off because it lacks even one notable extract from the archives, and would have found its individual songs clustered at the bottom. A tip of the hat to Chris Welch’s Led Zeppelin: Dazed and Confused: The Stories Behind Every Song, and much thanks to Barney Hoskyns’s Led Zeppelin: The Oral History of the World’s Greatest Rock Band, which came out a few years ago, a model of the form.

74.

“Moby Dick,” Led Zeppelin II

Ginger Baker of Cream pioneered the idea of the heavy, heavy drum solo; Zeppelin’s unmercifully hard pounder, the semihuman John Bonham, followed suit. You want to call Bonham a psychopath, but that’s almost too romanticized a word for his psyche. This is a guy whose sense of humor ran to taking a dump in a groupie’s purse when she wasn’t looking, such an alcoholic that he was known for drinking himself senseless and then urinating where he sat, notably on planes. Those are the sorts of stories told fondly by his “friends,” like the band’s longtime road manager, Richard Cole, in his memoir; from others, words like abominable, lout, and fuckhead come up. Anyway, Bonham’s hard, hard, hard pounding and his surprisingly swinging attack characterized Zep’s sound, and Page and various engineers in the studio found just the right dry but very broad way to record it. This grinding workout was stuck on the second album as a souvenir of the times; onstage, when Bonham would embark on an extended drum workout to give fans, their senses’ benumbed, a chance to catch their bearings; and, now and again, for the other three members to get a group blow job backstage from a willing female fan. Docked 30 or so notches for Bonham’s role in an infamous on-tour incident at Oakland, California, in 1979. A stagehand for Bill Graham had stopped manager Peter Grant’s son from ripping backstage signs down. In retaliation, Grant and a few other thugs in the band’s employ trapped the guy in a trailer and beat the holy shit out of him. Years of legal wrangling followed this deliberate and vicious assault. A footnote to the story is that Bonham had gone to the guy first — and kicked him in the balls without warning.

73.

“Royal Orleans,” Presence

After the triumph that was the two-LP Physical Graffiti, the band released Presence. The packaging featured a set of stock family photos with a mysterious obelisk added, courtesy of Hipgnosis, the go-to hep-rocker design firm of the time. (They’d done Dark Side of the Moon. Here’s some of their other work.) The real mystery was only where the band’s songwriting skills had gone. There are no significant songs on the album. Against stiff competition, this might be the album’s most forgettable track. It’s a contrived workout marked with illogical rhythm and musical change-ups. Chris Welch, in Dazed and Confused: The Stories Behind Every Song, unearthed this bit of history: The same issue of England’s New Musical Express that carried a “full-page heavily analytical treatment” of Presence included a small notice about a new band called the Sex Pistols. That article’s summation: “Let’s hope we hear no more about them.” It’s a reminder that even outsider bands like Zeppelin become accepted — and that there are always new outsider bands on the rise.

72.

“Hots On for Nowhere,” Presence

Another forgettable Presence song, a halting, stop-and-start boogie with a chorus of forced jollity. The title describes the song adequately. One of Plant’s worst lyrics, too.

71.

“Hats Off to (Roy) Harper,” Led Zeppelin III

A mess of blues lyrics set to a crudgy backing track from the band’s third album. Harper was a well-liked guitarist and singer who made quiet albums of interminably long, acoustic-y songs on them. He also appeared in the band’s concert film, The Song Remains the Same, along with Grant and Cole. Grant is an interesting case. He is a member of an important trio, along with Dylan manager Albert Grossman and David Geffen — the people who foresaw big, big money in the rock game and took steps to get as much of it as possible for their clients. The bands deserved their money, of course, but by all accounts Grant was a brute not above hiring gangsters, beating up kids he caught taping concerts, and the like. And, of course, his role in the Oakland incident is beyond the pale. (The account in the Bill Graham oral history is sickening.) Towering sweetmeats like Robert Plant aside, the world of hard rock was not known for its handsome participants. Even by metal standards, Grant looked a fright; he was an enormous blob of a man adorned with a thatch of grotesque facial hair that looked like it had been transplanted from the butt of a mangy hyena. And he spoke like one of the unintelligible supporting characters in a Guy Ritchie movie. Still, he loved Page and his band uncritically, and can be said to have remade the music business in his career. Grant died in 1995 of a heart attack, one of those rare people whose death gives the net humanity of the world a solid uptick.

70.

“The Crunge,” Houses of the Holy

Weird guitar sounds, even weirder lyrics. The band was trying to do James Brown here, and the result is the least interesting song of Zep’s classic period.

69.

“Gallows Pole,” Led Zeppelin III

I don’t understand this song, and was surprised when Page and Plant brought it, of all tracks, out for their reunion album in the 1990s. Some of the British bands of the period — like Traffic with “John Barleycorn” — had plumbed British folk in this way, but this didn’t really seem to be in the band’s wheelhouse. It’s based on a traditional tale of a woman being hanged. In Zep’s version, the guy’s wife fucks the executioner to get him off, but he still hangs him.

68.

“Candy Store Rock,” Presence

A faux ‘50s rave-up. Neither Plant nor Page is convincing.

67.

“For Your Life,” Presence

A big slide sound, some cooing from Percy, an extended solo, some drums bashing. For six and a half minutes. And then it flies right out of one’s mind.

66.

“Your Time Is Gonna Come,” Led Zeppelin

On the second side of their debut, misogyny takes over on a track unsubtle lyrically and musically. Wimmin! Some pretty organ work from Jones, though.

65.

“The Lemon Song,” Led Zeppelin II

A bruising post-blues workout with a live feel, another example of how the band blistered the genre. Still, there’s a lot of notes in this song but not much else. The band’s lack of respect for traditional blues form was paralleled by their lack of respect for blues songwriters. “The Lemon Song” is an example of the many times Plant stole so many established (and copyrighted) blues lyrics that they eventually lost some of their publishing, in this case to Howlin’ Wolf.

64.

“Thank You,” Led Zeppelin II

A purty little paean to ‘60s flower-children. I’m not buying it, though, in the end; it seems a bit forced, and not really in keeping with the band’s overall approach. There’s more than a little Spinal Tap in it, and the production is muddy, even on the remasters. Despite the sonic dominance of tracks like “Whole Lotta Love” and “The Immigrant Song,” Zeppelin was trying to broaden their palette on the second and third albums, to mixed results. It would be the fourth album before they made their claim to greatness.

63.

“Achilles Last Stand,” Presence

This rumbling, endless, unconvincing rocker was a worrisome sign that the band was approaching their second decade with declining assets. This was the lead track to the follow-up to the mind-blowing Physical Graffiti? The guitar solo — and worse, the guitar sounds — are pallid, and good lord: What is Plant singing about? The title is obviously a reference to ancient Greece, but we get a name-check for New York early on, and then something about Albion, which is a fancy-pants word for England. Docked a half-dozen notches for being interminable.

62.

“I Can’t Quit You Baby,” Led Zeppelin

Standard très heavy blues, appropriately credited to Willie Dixon, the great Chess Records producer and songwriter. Nothing too special here, just some of those concussive bursts of solo, with some sound effects that seem to go a bit farther than had been heard at the time.

61.

“Nobody’s Fault But Mine,” Presence

This rather routine track is one of Presence’s more interesting offerings, but that’s not saying much. There’s a distinctive but not very substantive guitar line; the workout at the end seems a lot of energy to expend on a second-tier song. There are some who insist that Presence is a good album, but they’re wrong — and the album is by far the band’s least radio-friendly. Zep’s biggest songs are among the most widely played on rock radio, far outstripping even classics like “Let It Be” or “Sympathy for the Devil.” BDS, which tracks radio play, says that this song, the biggest on Presence, has been played on radio a small fraction of the number of times something like “Whole Lotta Love” has, and far, far less than the radio hits from In Through the Out Door, too.

60.

“Since I’ve Been Loving You,” Led Zeppelin III

A long, slow blues, delivered fairly straight aside for some screechy interludes. This is in the realm of the sort of thing Fleetwood Mac, then led by the great guitarist Peter Green, was doing at the time, just louder (a lot louder), and of course Plant, who is intermittently impressive here, is in a different class. In the end, a curate’s egg — parts of it are excellent. Plant, incidentally, was supposedly the true blues aficionado in the ground, which explains a lot of the band’s stolen blues lyrics; Page, while schooled in the music, didn’t revere it the way many of his contemporaries did.

59.

“The Wanton Song,” Physical Graffiti

The sound of certain parts of Graffiti is muffled, the product either of artistic decisions on Page’s part that remain a mystery or the fact that the two-LP set was filled out with some songs from the archives. Plant squeals though a second-tier song from the set’s last side. A dumb song, you think — until a disconcertingly pleasurable instrumental break. Then back to the dumbness.

58.

“Tea for One,” Presence

Long, languid blues. It might have been one of the more winning tracks on Presence, but the uncharacteristically muddy production and extreme length sink it. Still, in the end, it’s the album’s best track. There’s an extended and very persuasive old-school blues solo from Page, but it’s a long four minutes to get to it, and another long three minutes after it’s over.

57.

“Custard Pie,” Physical Graffiti

Why this track led off Graffiti, an important moment for the band, is a mystery. The production is indifferent, lacking the arresting crispness of the band’s better work. The lyrics? A mess of blues posturings, some of them stolen.

56.

“Celebration Day,” Led Zeppelin III

An unmemorable grinder. At this point on the first side of the band’s third album, after the promising leadoff “Immigrant Song,” it was starting to sink in that III was not the band’s best work. It has a rep as Zeppelin’s soft album — the quiet numbers were there deliberately to show off the band’s varied musical interests. But too many of the songs are subpar. The lyrics here are a wan mixture of hippie posturing and vague stabs at social import. The backing track is boring.

55.

“Carouselambra,” In Through the Out Door

A massive assemblage from the band’s final album, their last stab at epic, dressed up with an agreeable guitar barrage of the first order to kick things off, and a failure nonetheless. The band somehow lacked authority at this point, really, to keep our interest through such throwback-y stuff. When your audience’s most common reaction to a new work is, “Is this still the same song?” you’re on the wrong track.

54.

Down by the Seaside,” Physical Graffiti

Zeppelin isn’t the band you really want to go on a bucolic getaway with, but this is what they gave you. Aside from the driven middle section, pretty non-notable and definitely filler, but on Graffiti it passes for a breather.

53.

“The Rover,” Physical Graffiti

Even some of Graffiti’s filler is pretty powerful stuff — it’s a killer chorus. But this is one of the more anonymous songs on the release. Too much of Graffiti lacks the sparkling production of the band at their best.

52.

“Out On the Tiles,” Led Zeppelin III

A nice shrieking chorus.

51.

“Four Sticks,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

Probably the least interesting song on Zoso. It grinds along, and we never find out why the owls are crying in the night.

50.

“Hey, Hey, What Can I Do,” (single B-side)

Because the band wouldn’t let “Stairway to Heaven” be released as a single, you hear a lot that Zeppelin didn’t release 45 singles during their career, but a few got out. This is apparently the only non-album song the band released during their time together, the B side of the unrelenting “Immigrant Song.” As such, it’s a nice, acoustic-based antidote for your ears. The band at their most charming, until you concentrate on the words.

49.

“South Bound Suarez,” In Through the Out Door

Coming right after the album’s back-to-form leadoff track, “In the Evening,” this labored throwaway from the final album, with a particularly screechy solo from Page, was a puzzlement.

48.

“Living Loving Maid (She’s Just a Woman),” Led Zeppelin II

One of the abiding questions of rock ‘n’ roll is why these four hirsute brutes — at least three of whom would probably have lived out sad and anonymous lives were it not for the mysterious goodwill of a benevolent god who created them at the one moment in history where their odd talents could make them rich, famous, and objects of shockingly inhibited sexual desire to a new generation of liberated women — spent so much time writing woman-hating lyrics. A lot of it was received nonsense, and of course they were products of their time. But their inability to see beyond that is a strong part of the case against the band.

47.

“Sick Again,” Physical Graffiti

The epic Graffiti’s envoi is a groupie tribute from Plant, married to an incongruously dramatic guitar-setting from Page, and a spirited solo, too. I find the muddled production and the tedious outro kills it, though.

46.

“Friends,” Led Zeppelin III

A groovy little acoustic-based number designed as a deliberate change of pace after the leadoff track, “The Immigrant Song.” There are a lot of weird things going on in the song, to no effect. A real mess.

45.

“Heartbreaker,” Led Zeppelin II

Thematically, this is basically the same song as Rod Stewart’s “Maggie May.” One is timeless, musically alluring, and emotionally rueful. The other is leaden, labored, and comes across as contrived. Page’s ferocious unaccompanied guitar-break was novel for the time, though.

44.

“The Ocean,” Houses of the Holy

A very big beat and a very big guitar line, exhumed by Rick Rubin for the first Beastie Boys album, in a visionary sample that brought a new generation of respect to the band: “Jesus, that is some guitar sound.” You go back to the track and marvel that, yes, that is some guitar sound — put to the use of a fairly meh song. Then ending fanfare is swell, however, another examples of the Page throwaways that would be the pride of many other bands.

43.

“That’s the Way,” Led Zeppelin III

A quiet, not-quite-convincing number from III. Page was trying to show breadth, which was fine. But, coming right after the sublime “Tangerine,” the song has the feel of being a deliberate stretch rather than coming organically from the band’s interests.

42.

“In My Time of Dying,” Physical Graffiti

One of the very long jams on Physical Graffiti, a major statement and a bid for critical respect. There is very little on the album that is embarrassing, and on songs like “Trampled Under Foot,” “In the Light,” “Black Country Woman,” and “Kashmir,” Page showed off a mastery of disparate organic forms no one then working in the music could match. This track, however, is not the album’s high point. First, you consider that time has not been kind to such constructions. The long, linear arcs seem torpid. Yes, those are some neat guitar sounds, delivered with majesty, but they are repeated ad infinitum, and often at somewhat slow speed. On the other hand, you get both slow and fast here. You marvel at the epic hard-metal setting for a traditional plaint about keeping one’s grave clean and lettin’ someone die easy. But then you reflect again that time has not been kind to such constructions.

41.

“Black Mountain Side,” Led Zeppelin

A moody acoustic number with a distinctive model tuning. The tabla is by a guy named Viram Jasani, one of a very small number of guest players on a Led Zeppelin album.

40.

“Ten Years Gone,” Physical Graffiti

By the mid-1970s, Page had the routine down — the studio ‘n’ guitars epic, scene set with an acoustic-y beginning, drama supplied by the big guitar burst. Repeat for six to eight minutes. Page delivers on the guitar work, and Plant steps up with surprisingly vulnerable lyrics, which seems to be a relationship that has lasted ten years, though the phrase ten years gone is perhaps not the most felicitous turn of phrase to describe it — it’s supposed to mean “ten years on” rather than “ten years wasted.” But in the end, it’s brought down by muddy production.

39.

“What Is and What Should Never Be,” Led Zeppelin II

A moody, almost jazzy change-up after listeners had their cerebral cortexes cauterized by the second album’s leadoff track, “Whole Lotta Love.” Doesn’t hurt that the words aren’t hateful. This is by any standards a minor Zeppelin song, but the loud-soft dynamics, more subtle here than in a lot of Zep tracks, and the bright sense of sound and space in the recording, work well. And yet another great fanfare outro.

38.

“Boogie With Stu,” Physical Graffiti

If you’d recorded a groovy studio jam with bashing piano courtesy of guest artist Ian Stewart, one of the founding members of the Rolling Stones and a key part of the Stones operation through much of its life, you might call it “Boogie With Stu.” Of course, you could also call it “Ooh, My Head,” seeing as how that’s the name of the actual song, which was written and recorded by early rocker Ritchie Valens, who died in the plane crash that also claimed the lives of Buddy Holly and the Big Bopper. It’s kinda funny to credit the song to the four members of the band and Stewart, too, and throw in a joking reference to “Mrs. Valens” — though it’s the kind of humor that allows one of the parties to go laughing all the way to the songwriting-royalties bank. Docked ten notches for song theft.

37.

“Bron-Y-Aur Stomp,” Led Zeppelin III

Bron-Yr-Aur is a remote cabin the band would go to to write. It was said not to have electricity or running water; Page paid for a caretaker. The name was misspelled on the original Zep album; should be “Bron-Yr-Aur.”

36.

“I’m Gonna Crawl,” In Through the Out Door

A nice-sounding, somewhat humble love plaint. Ten years into his career as a star, Plant seems to be discovering that need and vulnerability can be sexy, too. Page contributes a restrained guitar attack. As a whole, another sign of the maturity available on In Through the Out Door, which became the band’s last studio album. The band generally did a great job on their album covers. III had a distinctive spinning wheel hidden inside the record sleeve, with die-cut holes designed to show all sorts of things as you spun the wheel. Physical Graffiti’s cover was a shot of a pair of buildings on St. Marks Place in New York, with the windows cut out to let various pictures on the inner sleeve show through. In Through the Out Door was even more novel. Sold in a brown-paper wrapper, the actual album sleeve featured different photos from a bar scene, and on the back, a variety of odd close-ups of the scene, in black and white, made out of what looked like Ben-Day dots. Turned out that if you put spit or water on them, they turned color! Mind. Blown.

35.

“Going to California,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

Of all the acoustic-based numbers the band had recorded up to the fourth album, you had the feeling that the band was stretching to include the music, rather than letting it grow organically out of their process. To me, this is the track that shows how a truly heavy band could soften things up convincingly. Plant’s varied singing here stands out.

34.

“How Many More Times,” Led Zeppelin

Another statement of guitar and studio dominance by Page. The beginning, a huge, swaggery beat, is a little show-offy, but the groove it eventually hits — yet another of those minor Page riffs that would mark the high point of a lesser band — is a heavy one, indeed.

33.

“No Quarter,” Houses of the Holy

Houses of the Holy is the band at their height. The abstract songs here are even more abstract. This is probably some great war epic, but all you really notice is the sound texture — is that a Leslie the vocals are going through? — and Page’s lancing rumble of a guitar riff coming through the chorus. There’s a lot going on here, but too much of it is monochromatic.

32.

“Houses of the Holy,” Physical Graffiti

The title song of the band’s fifth album got left out in the end, and found itself a place on Graffiti. It’s a slow grinder. Plant’s vocals are, winningly, mixed up high. Not too much else going on, though.

31.

“Bring It On Home,” Led Zeppelin II

The closer to the second album starts out all folksy and bluesy, and then erupts. The riffs are fine, but second-tier. Knocked up ten notches for one of Bonham and Jones’s most rockin’ rhythm tracks.

30.

“Communication Breakdown,” Led Zeppelin

A quick and dirty rave-up on the lagging second side of the debut. Plant tries out some of the squeals that will make his mark on “Whole Lotta Love” on the next album. Page contributes some very crisp, very hard riffs.

29.

“Misty Mountain Hop,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

Percy finds some nice people in a park. Even the cops don’t harsh his mellow. But you wouldn’t know it from the grinding instrumentation.

28.

“Hot Dog,” In Through the Out Door

A little novelty rave-up from the multivaried last album. It’s a dumb song, I guess, but Plant’s breezy Elvis imitation and Page’s fierce guitar runs make it a lot of fun. From start to finish, one of Plant’s most coherent sets of lyrics and arguably his most nuanced — and amusing — vocal performances. Check out how he delivers, “I took her love at 17 / A little late these days, it seems / But they said heaven is well worth waiting for,” a lyric with — heavens — both distance and humor. “Hot Dog” is also just 3:15 in length, quite an achievement on an record whose average song length is more than six minutes.

27.

“The Rain Song,” Houses of the Holy

For all of Page’s production skills, some of the songs in the middle period sound occluded. The remasters bring out some depth — and make audible the drums — in this lulling mood piece, in which guitars are barely audible. It it too long? Yes — it’s a Led Zeppelin song.

26.

“Night Flight,” Physical Graffiti

A deceptive, gentle propulsive rush marked a gem from the last side of Physical Graffiti, anchored by a convincing strut of a guitar line. There’s a melody here, too: Jeff Buckley covered it to dramatic effect on the extended Live at Sin-é album.

25.

“You Shook Me,” Led Zeppelin

Zeppelin’s early blues workouts don’t mean much to us today. Almost 50 years ago, they were audacious reinterpretations of a catalogue still considered sacred. Even Clapton’s “Crossroads”— a high-octane version of a Robert Johnson classic — seemed tame next to Zeppelin’s unbridled, just-not-all-that respectful takes. This wild and screechy rendition, complete with some call-and-response guitar ‘n’ voice work at the end, was a new high, or low, in hard-rock blues. Upped five notches for documentary value.

24.

“Ramble On” Led Zeppelin II

An economical (less than five minutes, positively breezy for this band) rave-up that, over the years, has taken on more stature than it deserves. Yes, there are a couple of (wan) Lord of the Rings references later in the song, but they are out of keeping with the rest of the lyrics, and it’s not really clear that Plant had even read the books. (Did Plant think the line went, “One babe to rule them all”?) Still, crisply produced throughout, with one of Page’s more complex guitar assemblages in the chorus, and a rock-radio classic.

23.

“Fool in the Rain,” In Through the Out Door

Another odd song from In Through the Out Door. Anchored by a simple synth line and a very spare back-up, it feels at first like a misfire. But it turns out to be a fairly coherent love song that sees Plant haplessly left on a street corner waiting for a woman, and — for once — he doesn’t end up sounding like a complete asshole. The song’s musical simplicity is somewhat deceptive; the drums are running at cross-purposes to the melody, and there are a lot of musical twists and trends. None justify the song’s interminable length, but for Zep, humility and some of Plant’s most plaintive vocalizings go a long way.

22.

“Black Country Woman,” Physical Graffiti

I love this song uncritically, from the burst of left-in studio chatter that begins it to Plant’s “Whatsa matta withchoo, mama?” ending. That’s not an easy acoustic guitar line Page is proffering, it’s a deceptively simple (you try to re-create that riff on a six-string) acoustic number, marked by a crackling drum sound from Bonham and some nice harp playing, too. Yes, it’s a dirty-dealing-woman song, but it doesn’t come across as hateful.

21.

“Bron-Yr-Aur,” Physical Graffiti

Another tribute to Bron-Yr-Aur, in a rare instrumental track. Another track that shows how supple and protean Page’s guitar talents are.

20.

“Black Dog,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

Back in the LP day, side-openers counted for something. For their fourth album, upping the ante on all their competition, the band delivered two bashy hard-rock classics in a row — this song, and then “Rock and Roll.” This bruising leadoff, preceded by some faint, ominous studio noise, brought back the echoing Plant voice of “Good Times Bad Times” over a crushing and unrelenting guitar line from Page — though it was actually written by Jones — delivered at seemingly five different time signatures. The lyrics remain tattered old blues tropes, but no one could mistake the musical maelstrom beneath them for their older brother’s blues.

19.

“Trampled Under Foot,” Physical Graffiti

This stomping, brittle rocker should have been the leadoff track of Graffiti instead of the inferior “Custard Pie.” Page has at this point moved far on from the slow and sometimes labored riffs of the first few albums. (Compare this song to “Heartbreaker,” for example.) Here, he’s utterly frenetic. To my ears the song has a dry shrillness, a high-pitched trebly patina, that I associate with heroin. You can take or leave Plant’s jokey lyrics about car mechanics or such, but there’s no gainsaying the ferocity of the band’s attack. Historical footnote: A reviewer in Rolling Stone said the song, a rock-radio staple now for almost 40 years, reminded him of Kool and the Gang — a novelty funk amalgamation known at the time for songs like “Hollywood Swinging” and “Jungle Boogie.”

18.

“Dancing Days,” Houses of the Holy

Houses of the Holy is not often noted for its extraordinary sonics. This very trebly, highly mechanical track is case in point. Who knows what Plant is singing about, but the unrelenting guitar attack drives the song along and made for some of the most radio-friendly work of the band’s career. Even on this seeming throwaway Page’s guitar is inventive, creating an illusion almost of propulsion on the breaks and offering along the way a dizzying amalgam of sounds.

17.

“In the Light,” Physical Graffiti

One of the subtler and most pleasurable of the band’s various epics. It was written by Jones; in Dazed and Confused, Chris Welch says the band never played it live because the synthesizer Jones used couldn’t be kept in tune on tour. There’s are several great guitar sounds here, and a funkily odd instrumentation — that clavinet break, and the dead stop to let Page deliver a single silky rising guitar line. In the end, the band achieves something close to grandeur. Docked a notch or two for being the same song, repeated twice.

16.

“Rock and Roll,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

Zoso’s first side continues with these unbridled three and a half minutes of cataclysmic rock ‘n’ roll. One of the most dramatic guitar attacks ever captured on record; Page’s tone has a depth and a fullness no other band could match. Note how, in contrast to the severe crispness of most of his guitar riffs, here he lets the chords reverberate. The result: an utterly anachronistic nostalgic hymn to the 1950s.

15.

“In the Evening,” In Through the Out Door

Jimmy Page’s last great guitar moment on record. The leadoff track of In Through the Out Door has a panoply of guitar sounds that would stand with his most creative work; a flurry of notes melding into a huge bank of running sound that skids into full stops and then eases into lulling interludes. Late-career message from M. Robert Plant: “I need Zoo Love.”

14.

“D’yer Mak’er,” Houses of the Holy

This supposedly novelty number, half reggae and half doo-wop, was done as a joke; Bonham and Jones were said to hate it, and the band responded balefully when it was released as a single against their wishes and became a significant radio hit. Two ways to look at it: It is a crude faux reggae, to be sure, and kinda goofy. But somewhere on the road to novelty the band came up with something different. The bridge is a stunner. The sound of it made for a classic ‘70s radio single, one that jumped out of the dial. (The mix is significantly different from many other Houses tracks.) Page’s guitar solo, slow and literal for once, is a gem, and Plant’s vocals are unassailable. (The title, incidentally, is pronounced Jermaker, a British pun on Jamaica and “[Did]’ja make her?”)

13.

“When the Levee Breaks,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

At first this seems like another relatively innovative blues, if beating them beyond recognition counts as innovation — hardly the barn-burner closer you might want for an album with “Black Dog,” “Rock and Roll,” “Stairway,” and “Evermore” on it. But there’s a very hard drive to the arrangement, and a distinctive churning upbeat that resolves into a nice, plangent guitar break — with a very warped undertone to it — halfway through, culminating in an almost hypnotic slide rave-up at the end. Turn it up loud and give it your attention; it’s an underappreciated stunner.

12.

“The Battle of Evermore,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

Lovely, doomed Sandy Denny was the one of a trio of magnificent British female singers in the 1960s — the others were Linda Thompson and Christine Perfect, later McVie. Her voice was at once powerful and delicate, and one of her legacies was this duet with Plant, which is where the real battle takes place. I beg of you, do not research the lyrics, because I shall not then be able to protect you from what I shall call the “woe of aftermath.” But do bask in the song’s extravagant multi-tracked ululations, the dramatic echo, and the phalanx of keening mandolins.

11.

“Tangerine,” Led Zeppelin III

Soft Zeppelin at their loveliest. This plangent lyrical throwaway has been unjustly overlooked. You can hear fingers on the frets, nails or a pick passing across the strings, to add just a touch of humanity to spar with electronically treated pedal steel. There’s a minor drama here, and many shades of Page’s guitars, set like pastels in the glittering, nostalgic soundscape.

10.

“All My Love,” In Through the Out Door

A year after the release of In Through the Out Door, the band’s seventh studio album, drummer John Bonham died, choking to death on his own vomit after a day of drinking at Jimmy Page’s mansion. It was a fitting end for this not-quite-human. To their credit, the other band members never considered moving forward. There was a wan, highly uninteresting album of outtakes, Coda, and in the nearly 40 years since, but a small handful of instances where the three members played on the same stage at the same time. In the context of the never-ending, highly commercialized retirements we’ve seen from greedy coevals like the Who and the Grateful Dead, that counts for something. But it also meant that the band never had the chance to grow old and start to suck. I go into all this to point out that In Through the Out Door is a remarkable work by a band of their age, and on this song and several others, you can see the entire band moving forward toward a more mature music, past the thudding guitars and preening sexism. This song, written by Jones and Plant, is case in point. You could have imagined Led Zeppelin growing old playing such music; delicate and somehow meaningful, with touches of the old grandeur, all put to the words of a serious song, a tribute to Plant’s young son, who died in a car accident. I hear the sound of musicians having passed the point of needing to overwhelm their listeners. I hear a musician having passed the point of needing to overwhelm his listeners. John Paul Jones contributes a somber keyboard interlude, and then you can hear him and his master Page duet.

9.

“The Song Remains the Same,” Houses of the Holy

A blistering assault roughed up with sudden changes in dynamic and tone. Plant here is at his most squeally and porcine, but there is something riveting about Page’s guitar work. The high-speed solos are articulate and true, and throughout he keeps layering on new guitar sounds.

8.

“Immigrant Song,” Led Zeppelin III

The leadoff track to III doesn’t rest or flag for 2:26. This Norse mini-epic is perennially prized by metalheads (see, for example, Jack Black in School of Rock) for its attack, cauterizing even by Page standards, its straight-outta-Asgard lyrics, the wild sounds, and its being the source of the definitive Zeppelin aperçu— “Hammer of the Gods?!?!” — delivered by Plant with a hilarious Dr. Evil–esque lilt.

7.

“Babe I’m Gonna Leave You,” Led Zeppelin

If you’re going to have Brobdingnagian rock, for heaven’s sake, let it sound like this. This track is to my mind the most underappreciated in the Zeppelin catalogue. It’s all so simple — soft-loud, soft-loud. So what makes it work? Well, for one, things get really loud; Page tries mightily to approximate the sound of a mountain being dropped on your head. Two, it’s not a normal Zeppelin work. There’s no real guitar solo here. And finally, there are the words. There is something direct, plaintive, and unmisogynistic about Plant’s delivery. He’s not happy about it, but he has to leave (or “ramble,” as he puts it). He’ll come back eventually, and when he does, well, the pair will go walking in the park. But right now, he’s got to go away. Plant turns this simple situation into an emotional maelstrom of the first order. His singing, if anything remains of the blues idiom in it, is that idiom’s apotheosis. It’s also a match for Page’s chording, which is saying something. Upped several notches for creating the sound of a mountain being dropped on your head.

6.

“Over the Hills and Far Away,” Houses of the Holy

The opening guitar lines for decades were played by every young boy and girl with dreams of guitar-herodom alive in their heads. Sounds best on 12-string, of course, but you can make an approximation with six. There’s something charming in the acoustic opening’s slightly offbeat rhythms and friendly fills. It’s all there for another purpose, though — the blast of high-volume electric guitar that comes in at 1:27. Everything works, right up to the burst of abstract sound that sees the song out.

5.

“Dazed and Confused,” Led Zeppelin

”Dazed and Confused” beats the shit out of just about any hard-rock ‘70s classic you can name. Ominous beginning, another of those full-bodied Plant vocal performances, a half-dozen or so unique noises, Jones and Bonham both at top furious form — and the mother of all guitar barrages, too. Page does everything to a guitar you can do over the course of this song, from delicate harmonics to sawing it — and then beating it — with a violin bow. It’s the best example of how Zeppelin created a drama in their songs that drew listeners in and fended off boredom. (Compare, for example, the Who at their supposed best, on the longer tracks of Live at Leeds. The Who were an impressive band, but a lot of their stuff is tedious.) Docked one notch for the line, “The soul of a woman is created below,” artless even by Plant standards. Docked three additional notches for songwriting theft. There are almost a dozen instances where the band has been accused, with varying degrees of seriousness, of ripping off lyrics or guitar riffs. Of all of these, this is the clearest and most egregious. Page didn’t just steal a riff from ‘60s folk singer Jake Holmes; he stole Holmes’s whole song. Page took the ominous opening, the melody, the structure and, most crucially, the dynamics — and, on the band’s first album and the live “Song Remains the Same” set, solo songwriting credit. “Dazed and Confused” isn’t a Led Zeppelin song; it’s a cover of another artist’s work. It’s well established that Page got the song from hearing Holmes. It was even credited to Holmes on a live Yardbirds album Page played on! (One suspects that if Page had written the song, he would certainly have demanded a correction, and the royalties.) Yet he took the credit for himself on at least two albums that have sold untold millions of copies, earning something in the neighborhood of a half-million in sales royalties and radio play. Page has lied about it in interviews, too — but eventually settled out of court with Holmes. Doesn’t take away from Zep’s concussive production and playing on one of rock’s all-time most-powerful tracks. Just means we should remember that Page as a young man was a petty (in this case, not so petty) thief, and as an older man capable of lying about it when caught.

4.

“Stairway to Heaven,” Untitled, a.k.a. IV

Like everyone else, I have lost my ability to hear this song, dragged down as it is by overfamiliarity. But I have to say that many times over the years — in a parking garage in Atlanta, on a freeway in Chicago, on a rainy afternoon in Berkeley, while running on the Mall in D.C. — it has come on when I didn’t expect it, and I have been caught up in it again. High dynamics; a set of lyrics not entirely buffoonish by Plant standards; a restrained, then intense, then overwhelming band attack; and, finally, that solo to end all solos, Page at his most utterly articulate and dramatic, keening and at times so fast as to beggar belief. That speed, logic, lyricism, and intensity make all other guitar solos seem puny. I don’t want to put too much onto blundering poesy of this sort (that “bustles in your hedgerow” is silly, indeed), but I will point out that the song has a point — you can’t buy a stairway to heaven — and further that in its arcing, thrilling penultimate line, we can hear a statement of intent, strength, and resolve in the face of that other much more malleable ‘60s survivor band, the one that insisted on Rolling.

2.

“Whole Lotta Love,” Led Zeppelin II

A titanic recording; pace George Martin and Jimi Hendrix, this represented the farthest reaches of unquestionably pop-based studio sound and brauvura guitar-slinging of the era. Page’s riff — implacable, huge, and priapic, more thunderous (and menacing) than “Satisfaction,” more ominous than “Smoke on the Water,” more primal than “Louie Louie,” and delivered with a machinelike intensity — defines rock at its hardest. Plant’s singing is a definitive set of authoritative declamations and howls of desire that pretenders like Roger Daltry, Ian Gilliam, and Ozzy could only dream of, and Page takes it to another dimension in the studio, everything from the backward echo you can hear if you turn the damn thing up to the fact that he keeps the drums off the tack for the first 30 seconds, making the hardest rock you’d ever heard suddenly even harder. Then there’s the daringly long percussion break, culminating with paroxysms of noise, some heavy breathing from Plant, and then, almost matter-of-factly, the return of that guitar riff. Docked a notch for ripping off lyrics from Willie Dixon’s “You Need Love” (which contains the lines, “Way down inside / Woman, you need love”) and forcing the aging bluesman to sue them for credit.

2.

“Good Times Bad Times,” Led Zeppelin

In one sense this is a cartoon, and Zeppelin would outgrow such stuff. But it has to be noted that this is the sensational leadoff track to a debut album and career, the first echoing, crisp, very hard guitar chords heralding something very new. The cocky, knowing lyrics, the firehose of sound, and the très cool guitar work all announce that the terms of the debate have been changed; indeed, Page’s flurry of notes at the end of the first verse ends the debate with a slap upside its head.

1.

“Kashmir,” Physical Graffiti

When the band’s fourth album came out, Rolling Stone mentioned “Stairway to Heaven” only in passing. When, three years later, Physical Graffiti came out, a grudgingly positive lead review in the magazine praised “Stairway” to the stars — and dismissed “Kashmir” in an aside as “monotonous.” By this point, Page had plainly mastered the fast-slow, soft-hard dynamics of sound, with his guitar, in song construction, and in the studio. For “Kashmir” he decided to experiment with stasis. The song starts out at a high pitch and stays there, producing a hypnotic M.C. Escher staircase of a guitar riff; always moving upward, yet somehow always coming around to create itself again. And it’s all built on a herky-jerky beat that Bonham (dismissed as “plodding” in the Rolling Stone review) uses to drive the band forward. No other hard-rock band of the time recorded a song like this, and no other group ever would — and it’s probably the band’s most popular song after “Stairway.” A postscript: Remember the Sex Pistols, the band dedicated to tearing down the rock Establishment in general, and dinosaur rock bands like Zeppelin in particular, on the rise just as Physical Graffiti was released? Close to a decade after the Pistols’ demise, their escapee leader, John Lydon, debuted his new live ensemble, a cacophonous aggregation called Public Image Limited. They opened their shows with a stunner: a grand, precise, sweeping, and wholly admiring version of “Kashmir” — a potent example of the respect from unexpected quarters that accrues to those who, you might say, decide to be a rock, and not to roll.