It’s a “gray and miserable” day in western England, but Robert Plant is in the mood to be challenged. If anything, the mist is making him stronger.

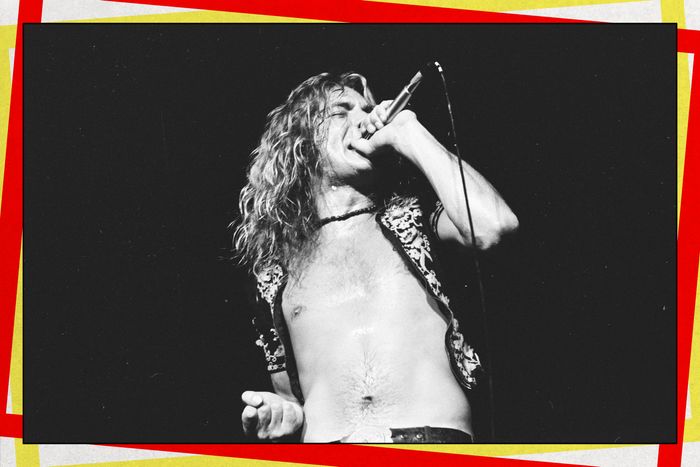

We’re connecting in late December, more than a year after Plant released his stunning collaborative album with Alison Krauss, Raise the Roof, which is in contention for three Grammy Awards at this year’s ceremony. It’s this type of unpredictable spirit — the project, like its Album of the Year–winning predecessor, Raising Sand, is rooted in bluegrass and country traditions — that has guided Plant for the majority of his career. He was, of course, the platonic ideal of a rock front man with Led Zeppelin until their disbandment in 1980 — his voice a golden hammer, and his lyrics an oft-inscrutable scripture of raw power, for his soul partners Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham. In the ensuing decades, Plant’s momentum was infinite, even when his music digressed and changed with purpose when he embarked on his journey as a solo artist in 1982. As he likes to put it, “I’ve sort of woven my way through it all.”

Plant and I chat for well over an hour — “The floodlights are lighting up in the next town,” he observes at one point — only saying good-bye when he realizes he has to meet Bonham’s sister and her husband at a nearby soccer game. Before that, though, he wanted to convey a message to everyone reading this piece: “I’m fully aware of the fact that there are two paths you can go by with these types of questions,” Plant says. “You can either send the whole thing up because it’s such a long time ago and say it is what it is. Or you can actually explain some of it away. It doesn’t mean to say that any of the processes that got me to those songs are the ways that I live my time now. Nonetheless, I still know those stories, and that’s what got me to those songs.” Mercifully, he chose the latter path this time around.

Song that’s built the strongest mythology

It may not be immediately recognizable as such, but I would choose “Achilles Last Stand,” from Presence. Much of my lyric and melodic input I now see wrapped in these journey songs. Think of “No Quarter,” “The Song Remains the Same,” “Kashmir,” and “Ramble On.” And today on Raise the Roof with “High and Lonesome.” As a teenager, I was drawn to the work of C.S. Lewis and Lewis Spence and the unknown works, or mostly forgotten works, of J. R. R. Tolkien. Later on in my teens, I started reading Beowulf and the sagas, which reflected a kind of deeper connection with the islands, which are my home. The little shards and shivers that make myths and seek the magical adventure.

My first influence was coming face-to-face with other times before the mass onslaught of everything that we now know. In the places where my parents took me and in the place where I live even now — which can’t be more than about six miles from where I was raised — I saw another time and a difference. The whole idea of quest and the value of movement. I think these islands from which we hail were perhaps some of the last areas of Europe, and if you like, the central Mediterranean, that really did move out and out. This area that we live in and around was once considered to be the end of the world. So people came through here. I was intrigued because I could see it in the buildings and in the landscape long before colonialism. But then, of course, it was always colonialism anyway. It was far more random and a lot more basic, but people were always on the move and finding new expressions and bringing new stuff through. New art, new use of materials, raw materials, bringing poetry, and bringing the mix of the bloods.

So, yeah, “Achilles Last Stand.” I spent some time in Greece, probably about six or seven months, after a car wreck in 1975. I was unable to walk. That particular song’s lyric relates to the absolutely desperate need to get out of the jail, out of the wheelchair, or out of the whole syndrome of being stuck in wherever I was. I longed to head back to the Atlas Mountains, to the place where it was solace and joy, but at the same time, intrigue and adventure.

Song whose meaning has changed the most for you

I think in all my times and all the changes that I’ve created and that we all create — the thought and the written words — everything rests in a particular moment. Then we move along and we leave that moment of enlightenment or madness or whatever behind. So for me, it makes no sense to consider a distance and the meanderings of such a long time ago. I mean, does “Black Dog” work anymore for me? It did in 1971. Does it represent me now? It doesn’t represent me now, but maybe it still does in a way. I was leaning on a lot of those Mississippi sort of plays on words. It seemed to fit in with the blues at the time. But if I look back at it now, do I really think its meaning has changed? No, because it was written in the spirit of the time. It happened and then you move on. Look, it’s 50 years later. It’s just a bunch of terms and phrases taken from African American shenanigans. Whether it’s Beale Street in Memphis or Clarksdale in Mississippi. It’s just these are all a bunch of things put together in straight lines.

I’d only ever co-written one song until I teamed up with Jimmy and John Paul Jones. John Bonham and I took his mother’s car and drove down to the first meeting and rehearsal. So I didn’t really know too much about writing. I was wedged in the tail end of Dion and the Belmonts — Dion DiMucci is a spectacular singer. I also loved the lyrics and the shuffle of what was going on with early Buffalo Springfield. The thought process was far more coherent and challenging coming out of America at the time. So I suppose I was kind of stuck in this antiquarian approach, of sticking a lyric to a riff. Was it cute? Yeah, it was cute. But did it make any sense? I was 19 when I went to the first rehearsals and 20 when the first record came out. So does “Living Loving Maid (She’s Just a Woman)” work for me now? Well, I can dig it, but I don’t really know the guy who wrote it. I wouldn’t recognize him in the street.

Nerdiest song for Tolkien lovers

This is a windup, isn’t it? [Laughs.] Bearing in mind that I’ve been hung out to dry a million times for being a sort of sad old hippie going on about Frodo. But I was visiting Frodo when he was about as well known as the most obscure book in my library, when Tolkien was a forgotten entity. So that gives me … no, that doesn’t give me any parlay in this situation.

I have to say that “The Battle of Evermore” is the right thing for me. Tolkien was a professor of medieval history and he lived and taught about 30 miles from where I’m sitting. He took his inspiration from the landscape, which I’m a part of now. In a few years, I’ll definitely be a part of it. In fact, hopefully it’ll be a few years. The Shropshire Hills and the Clee Hills are where he sat and he saw the Shire below. In the Stiperstones and Mitchell’s Fold, where even now as dark as it is, Eadric the Wild will be moving across through the stone circles to banish the Normans back across the River Severn. I’ve been reading and studying this stuff and finding all the points of reference between myth, fairy tale, and reality, because it runs really close. These stories that exist in what you would call post- or pre-romance or whatever. If you put the tracing paper onto the map of these particular areas of the Welsh borders, it’s all there. You can see all the places that became evocative enough to carry on down through with the great stories. The eternal rub of cultures is unremitting in this area.

The fact that “Evermore” was the to-ing and fro-ing, if you like, of dance in the dark of night, there’s always been something quite evocative about this area where I’ve been raised. I’ve always been as into the world as possible. I have a romance with Morocco — southern Morocco, specifically. And the Hill Country of Texas, Oregon, and Montana. It seems to me that it’s all about this great vastness of the expanse where there are so few people. It goes back to what we talked about with the idea of “journey songs.” I think “The Battle of Evermore” is that ebb and flow of the constant rub of cultures. There’s no time more evident. It’s here everywhere. At the same time, you have to understand that I’m fully aware of the fact that compared to a big black flag, to the stuff that really makes me howl with satisfaction in a contemporary world, this is another thing altogether. We care a lot. It’s a dirty job, but someone has to do it.

I was just thinking about my history books — where I go sometimes and where I know there’s still a long boat buried in the sand. I probably need help. I probably need to go talk to somebody about this, but no doubt he’ll have a helmet on with horns.

Finest acoustic song

There’s a track on Mighty ReArranger called “All the King’s Horses,” which I felt was pretty good at visiting a Latin acoustic track. Now as far as acoustic goes, with a piano accompaniment from Carry Fire, I would say I felt confident about a song called “A Way With Words.” This is kind of the youngest, the kid brother of another one, called “A Stolen Kiss.” These songs had gotten so much air. They gave me a lot of room to stretch the lyrics and get into the actual sound of the words themselves. My musical personality is the ability to sit down and work on ideas and themes. I can be equally as effective and do the same amount of damage, perhaps more so, by using drama and restraint. Because if you cut these things right and make sure that the air around you knows what’s going on — everybody has their place and their electric moment — then it’s nice to visit and trust vocal lines here and there as a punctuation, or as just to make a point.

Song that always reminds you of John Bonham

Ironically, we go back to “Achilles Last Stand,” which is probably what I’d first say. I could say “When the Levee Breaks.” It was an absolutely stunning recording. John is playing such a sexy, ridiculously laid-back and held-back groove — he bought us a lot of credits when sometimes we were the guys at the front of the band and behaving a little coquettish. But I keep thinking of him playing on “Achilles Last Stand.” You just needed to listen to what those three guys were doing in the studio. Listen to Jonesy with the eight-string Alembic bass. And Jimmy’s solo? It’s just really, really something. Sometimes I really just had to get some superglue and stick myself onto the tape somehow with a countermelody because it was relentless. There was almost no way in to write something and make it a vocal performance along with the incredible instrumentation. There was not really a great deal for me to do, except what I ended up doing.

Most powerful song to perform live

You can shove the “golden god” bit because that’s just when I play tennis and soccer. And that’s not very often. [Laughs.]

The most powerful song to perform that I’ve felt, in more recent times, is called “Embrace Another Fall,” from Lullaby and the Ceaseless Roar. The Sensational Space Shifters were a mix of musicians — my brothers indefinitely for the rest of my time. This song and the projection of it into a crowd was a meld of everything I hold close to me musically. Their performances were jaw-dropping and dramatic. The personality of each player flooded the stage, and it was unbounding. Although it was organized with the dramatic and the explosive, it still had a sort of crazy way it would take off and dissolve again, and return to a West African riff and rhythm. All the lyrics are so poignant to me because it’s about my return to the Shire. For all the things that I really want to do, for everything that I’ve tried to think I’m a traveler, I ultimately keep coming back. The Shire draws me back and sometimes it leaves me in pieces as I take off. The tension and release of “Embrace Another Fall” has been a major moment for me in all my time. It was so difficult to get it there because it was crazy just trying to keep it under control. But there it is.

I’ve always spent time in North Africa. I’ll sit somewhere out of the way in the shade and listen to life go by. I listen to the musicians moving around the cafés. The suburban players who play a sort of inverted cymbal that they bounce on their knees and play with the fretboard facing the onlooker. It’s another way of doing everything. I became more and more engrossed in it. From my adventures in 1971 and 1972, I got Jimmy to come out to southern Morocco to work on “Kashmir.” I brought the whole thing home with “Embrace Another Fall,” because I’ve taken elements of everything that I loved and that trip.

Song you covered that might be better than the original

Do you think that I could actually give you an answer to that? I see it because people have covered our songs throughout time, and it’s a tough call, because everybody reads a song differently. For example, Alison and I perform “Searching for My Love” on Raise the Roof, which is a cover of Bobby Moore’s song from the 1960s. But it’s not better. If you see all these pieces that I’ve shared with Alison and the musicians on Raising Sand and Raise the Roof, they were expressions in the room at the time when we were piecing the stuff together. It was how the guys read it, what Alison’s comments were, and how we sang together in a rough form. As well as the musicians — superlative players who could hear how we were dealing with it vocally and us with listening to them. We needed another way to consider the song. All of the originals were special moments in their own eras. They were never to be improved, really, just to be revisited.

Most questionable music era

I’m not being smug, but everything I go into, I go into with my eyes open. I try things that sometimes depend on whether anybody has any time for what I do after all these years of pummeling the media and sort of nuance-ing my way through it all. I can’t really complain. Because am I thinking about whether the public accepted it? Or am I thinking about whether I accepted it? Well, it has to be how I feel, because there are many other options all of us can take who’ve been around this length of time. We can give up because there’s nothing else to offer. Or we could just write and sit back on our laurels.

After John passed away and there was no Led Zeppelin, there had to be a way to go. I floundered around a lot because until I was 32, I was in some kind of wild and absurd adventure. I went through all that stuff. I’ll write with other people. It’s a very intimate thing to do. It’s hard for anybody to expose themselves musically. Other people with me, and me with other people. I have a lot of songs under my belt, which I co-wrote with the members of Zeppelin. It was a lot to live up to. I had a lot of people who gave me support and strength around that time, so I suppose the first two albums were driven by great friends.

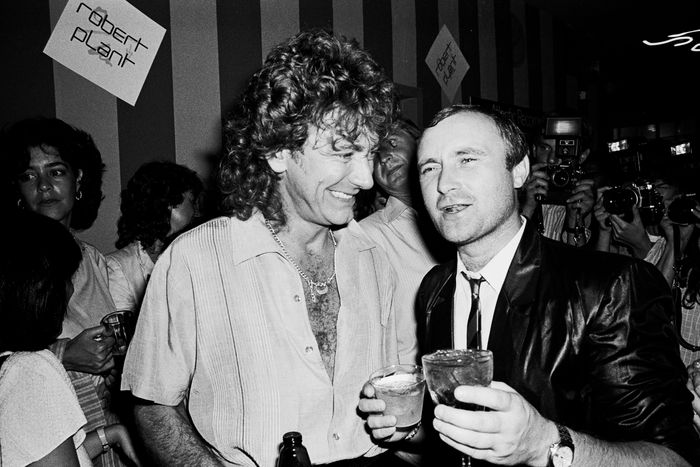

Phil Collins especially was a driving force and had positive energy with the first record, Pictures at Eleven. It wasn’t a difficult job to get together with other people, it was just whether or not we could cook it properly. With Phil, it wasn’t so much advice as encouragement and consideration. He was taking no prisoners. He would only allow himself a short amount of time to come to the studio in Wales and make it work. Nobody was hiding behind the performance. Then he came on tour with me and basically said, “Robert, the guy that sat behind you for all those years was my hero.” That was it. He said, “Anything I can do to help you to get back into fighting shape again, I’m here.” That was at the time when “In the Air Tonight” came out. Yet he was still mixing and working with me while kicking off a particularly impressive and successful time for himself. He’s a great spirit, a good man.

By Shaken ‘n’ Stirred, I was so determined to become the opening act for Talking Heads. So I started writing more and more oblique pieces of music — embracing what had become new studio techniques and stuff. I probably lost my way, but then there are so many LPs in my being, so you have to live with it and live by it. On the other side of the coin, I came roaring out of it and made an album like Fate of Nations with Richard Thompson and Nigel Kennedy. I came back onboard again. I think that was probably where I finally did find my way out of the passing of Led Zeppelin.

Your stream of consciousness watching Ann Wilson cover ‘Stairway to Heaven’

Look at the company I was keeping that night. Who was I sitting next to? What was going on? I didn’t even know the people anymore. How did we move across from being a British blues band to this ridiculous achievement? Well, ridiculous is a multifarious term. We all stood back at the end of the sessions, reeling from the transitions throughout the song. But “Stairway to Heaven” has its own life. Later I often felt estranged. It began intimate and vulnerable and sincere, and then the years carried on. It was no longer ours and neither should it be. Now it’s out there driving people to distraction and then maybe driving a hard bargain.

I’ve left so much of it all behind. And that night I was watching a reenactment — clever, well intentioned, and respectful. I was in the gallery peering and following an excellent display. Me and my contribution to it all were hung out to dry in the land of timeless tributes, so far from the cover and the scene, and so far from the home that we’ve given it. I felt estranged from the whole deal, from the song, and the fact that the years did carry it through. It had its own impetus. I watched it go. It was like a beautiful feather, balloon, or bubble. Something out of a clay pipe that had been blown with soap.

It was just something that I’d never, ever thought I would look at from this gallery. I didn’t ever see myself as smarting around seeing an artist’s impression of it. I knew it was coming — the Kennedy Center told us to expect something — but I didn’t know how it was going to be. It was a spectacular performance. I’m now a voyeur. I’m not responsible for it anymore. I’m not in guitar shops being told not to do it. I’m not going down the aisle at a wedding playing it with a flute. I love the song. It came upon me and stripped away all the years of being a part of all that. It just rubbed it right back to the bone. Because maybe it was all over for us a long time before it was all over. It was definitely all over without John. I mean that. We’re talking here about one song from 50-plus years ago. It’s just a magnificent performance to watch and it kills me every time. It kills me in two or three different ways. It’s just like, Oh my God.

Some people are completely trapped in their achievements, and that must be real hell. But perhaps one of the things about “Stairway to Heaven” was that the development of the song was exactly that. Somehow it was something very, very special, which I don’t really have a great connection to. But that night at the Kennedy Center, it made me remember that I had some responsibility, for better or worse, for that song. It wasn’t really about who did a great job, although Ann’s a spectacular singer. The whole choreography of it was blindingly sort of a “we’re not worthy” moment.

Why you said yes to School of Rock’s Led Zeppelin music cue

My response is: Why not? Our songs didn’t come from Valhalla. It’s not a preferred destination, either. I like the idea of taking the hammer to another time. Jack Black made a magnificent meal of it. It’s a killer guitar riff. What a shame “Immigrant Song” isn’t easy for kids to play, by the way. Everyone gets it, young and old. It’s a great song. Not only slightly ridiculous but ridiculous. Considering that we wrote it in midair leaving Iceland — a fantastically inspiring gig and an adventure, beyond which there will be no books written. To give it to the kids is important. Send it up, send it down, and just keep sending it. Just dig it because there’s no hierarchy.

There are great risks. There are risks that are immediately attractive. Jimmy Page has got that thing down. I thought “Immigrant Song” was great because it goes back to the Dark Ages effect on my being. I’m sitting here looking out into the darkness in the building that was built in the 15th century. It’s not a fancy building, it’s just a building that’s been brought back from a thousand different deaths. I know that before the Civil War, before Cromwell came through here, and before everybody would hide. Before, before, before, before, before, before. That Viking side of stuff is very funny. They used a huge fuck-off drum to choose the speed of the oars. Everybody’s seen Tony Curtis and Kirk Douglas in The Vikings. It’s just so evocative. So to give it to the kids, it’s great. I mean, Jack Black’s got it right down. He’s that risk. All of my grandkids have all been able to play Jack Black’s riffs. I think it was exactly the right thing to do, with School of Rock, to blow our myth up into the sky for a while. Because it’s all myth. It doesn’t matter. I’ve watched the film and find it funny.

I’m not responsible for all the decision-making when it comes to where we allow our music. It’s group decisions. There are two Capricorns and one Leo. We have to go through the whole thing together. Not to generalize, but quite often we’re presented with a scene that’s in the script or cuts of a film. When there’s something uncomfortable, unpleasant, or overtly just not the right place for our music to be, we say no. The music is dynamic. There it is, sitting there, and happily waiting for romance or nuance or drive that should link to a film with substance. But those are hard to come by. It’s not easy to find that. A lot of stuff is completely tasteless. It just goes straight for violence and dynamics. So when good ones come, it’s a different story. You can’t put it in the wrong hands. We’ve already done too much of that.

Fondest memory of The Starship, Led Zeppelin’s private plane

I’m going to make it nice and PG. I remember The Starship well. It was a thrill, because it meant we could leave shows, get to the next place, and get some rest and all the stuff that people do. When the plane landed for our first journey on one of the tours, you could barely see through the dry-paint work on the side of the plane that read, “Led Zeppelin, Elvis Presley.” They hadn’t quite finished the paint job. The planes were quite often just on their last legs before they ended up in the boneyard down in Arizona.

I remember one time we got on the plane and took off from Dallas to New Orleans. John Bonham was in that period of time where he wore a fedora and a black cane with a silver top. We got up to about 8,000 feet or whatever it was — pretty low. He finds it’s time to quickly visit the bathroom. And as he opened the door, his hat blew off and was sucked down the toilet. There was this great sort of whoosh. The guys that were back down on the airstrip had forgotten to rescrew the chute where the toilets were emptied, so there was a tank underneath the bathroom and they forgot to put the cap back on. There was absolutely no pressure. So John had lost his hat, but then we all lost our minds because we realized that we couldn’t go any higher because our ears were starting to go. [Laughs.] We flew from Dallas to New Orleans at 8,000 feet.

See, this is the trouble. There are so many movies and so many things I know that are absolutely hysterical. I mean, never mind the mystery. We can do without the mystery and just talk about the crazy things that happened. All’s well that ends well. It was just another night in paradise.

More From The Superlative Series

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music

make you sweat, gonna make you groove.” Perhaps the most Tolkien-esque stanza is “The Queen of Light took her bow and then she turned to go / The Prince of Peace embraced the gloom and walked the night alone.” Plant declared, “I’m a golden god!” in 1975, a nickname that has stuck with him through the decades, even though he doesn’t care for it anymore. Debuting in 2012, the band, led by Plant, focuses on world and blues-rock music. They also supported Plant on his two solo albums, Lullaby and the Ceaseless Roar and Carry Fire. Indeed, Collins somehow made time to play drums on the majority of Pictures at Eleven’s tracks, as well as serve as Plant’s drummer for the subsequent tour. This was after Collins became an international sensation with Face Value and Genesis’s early-’80s output. In addition to Ann Wilson, Nancy Wilson is there on guitar, as well as John Bonham’s son, Jason, on drums. About 100 singers and instrumentalists also supported them onstage. Vulture previously talked to Ann about the performance, and you can read that full interview here. Recent Hollywood projects that Zeppelin deemed worthy enough for their music include The Big Short, Thor: Ragnarok, and Sharp Objects. Michael McDonald once told us about the Doobieliner: “It was a quirky plane with a lot of weird jerry-rigged parts … it really was a death trap.”