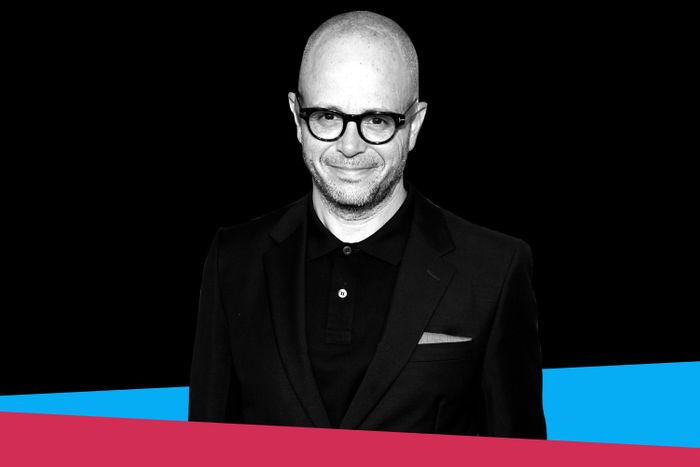

Can Hollywood ever just end a story? Game of Thrones, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, everything Marvel … it can feel like endless intellectual-property mining is sucking all the money and energy and attention out of the room — to the detriment of newer and smaller ideas. Damon Lindelof, who built a reputation for knowing when to end things through his work on ABC’s Lost and HBO’s The Leftovers and Watchmen, joined our podcast, Into It, this week to talk about his experiences making (and concluding) those shows and the pressure creators face to keep a good thing going.

You can read an excerpt from the discussion below, and be sure to check out Into It wherever you get your podcasts.

Subscribe on:

Sam Sanders: How do you say no in Hollywood? It seems that whenever something works onscreen, there is more pressure than ever before to keep it going or bring it back from the dead or revive it or make a sequel or a prequel or do a spinoff or make a new multiverse to make the world even bigger. Do you think it’s harder than ever to say no?

Damon Lindelof: Harder than ever. It’s always going to be hard because once you’ve got someone’s attention, you want to keep it. And so the idea of letting it go and not knowing if you’re ever going to get it back again is sort of like it’s antithetical to the way that we’re wired.

From a slightly sort of more cynical standpoint, this is a business. It’s an industry. And if you make a couple of great Marvel movies, the instinct is, We need to make more Marvel movies, and we need to expand this. And I have this sort of interior feeling of like, Wow, I wish they made less because it would make each one that came out a little bit more special. But I watch all of them, Sam, all of them.

You’re better than me.

People don’t want things to end. I do.

As someone who is able to say no and stop the thing, can we talk about perhaps your most famous no, about how Lost played out? You’re making this show, and ABC decides early on that they want it to go ten seasons, and you say, “No, we’ll give you six.” And then you even say, “We’re going to make fewer episodes per season than the norm.” That would be so hard to even ask for now. How hard was it to do back then?

Well, it seemed impossible at the time. At the time that Lost started, the primary critique of the pilot was “How are you going to keep this up?” There’s this big cinematic plane crash, and then you start introducing 14 major speaking-part characters, all of whom we’re going to be tracking. And in addition to that, the island that they’re on they’re not going to be leaving at any time soon. The show’s called Lost, so they kind of have to stay that way. Are you going to run into the Gilligan’s Island problem where the audience starts to get frustrated?

And my response to that always was like, “You are right. So let’s design a finite beginning, middle, and end.” ABC just didn’t want to engage in that conversation. At the time that they picked up the show, they said, “Make 13 of these, and let’s see how it goes.” It was such a ratings hit that it became clear to me instantly that all conversations about ending the show would be over. I said, “Hey, guys, we can’t keep this up forever,” and that’s when ABC said, “Oh, we were thinking more like ten seasons.” The compromise ended up being six, but I personally wish that we could have done it in four.

Even just hearing you talk about wanting to do four, having to do six, but pulling them back from ten — how hard would that conversation even be if you were making a show like Lost now? Because I compare it to a thing like Stranger Things. And I like that show.

Me too.

Every season, the kids kill the aliens, and yet they come back because they have a thing that works in this fragmented viewing economy. Would you face more pressure making a show like Lost now to just keep it going?

Yes to all of the above. But what you do now is — and this is certainly what we did on Watchmen, which is at the very early stage — you just say, “I want you to know that this might only be a season. You know we want to design nine or ten episodes with the beginning, middle, and end. And here’s why we would do it that way. Could there be another season of it? Maybe, but that’s not the plan here. What do you think?” And if they say, “We’re not interested in picking up anything that isn’t multiple seasons,” then they don’t go for it.

But I do feel that I see creators in 2022 saying, “I have a five-season plan, and that’s what we’re going to do. And then we’re going to be finished.” I love the fact that when Harry Potter ended, J.K. Rowling was specific in saying, There’s going to be seven books, and I’m going to bring the story to a close. And did. But then there was a play, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

And then the prequel movies, which are still happening.

For sure. I don’t begrudge them the right to keep it going. I’ve made prequels and sequels and reboots, so I can’t be a hypocrite and say, “God, come up with an original idea.” Meanwhile, I’m making two Star Trek movies and Prometheus.

I wonder also how much of this is about the changing relationship between fans and the folks who make these shows and movies. There was this really weird story in the news last week: Superfans of Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story got pissed waiting for season 11 of that show because they said he wasn’t giving them enough behind-the-scenes information about the new season. So they tweet, We’re going to go on strike. A media blackout until Ryan Murphy gives us something. And the next day, Ryan Murphy announces the launch date for American Horror Story season 11.

Wow.

And you’re like, Whoa, fan service has gone to a new level. How much is the “keep these worlds going”–ness of it all tied to fans just being louder than ever and demanding more than ever?

For those of us who are working on a television show or a movie, we’re investing many, many hours, days, in many cases years of our lives to these artistic pursuits. But the fans do the same thing, and they have real relationships. The more energy that we invest in these things, the more entitled we begin to feel that we should have a say in what the outcome is.

One of the things that I was fascinated by, as it related to Lost, was that one of the two questions that we got asked most often was “Are you making it up as you go along?” And the fans wanted the answer to that question to be “Absolutely not. We have a plan. We are executing that plan and understanding that not everything is going to work, but we’re sticking to the plan.” The second question that they asked most often was “What input do we have as fans? Are you listening to” —

But do you feel like you should have to listen to them at all?

Here’s the thing: They want the answer to be “We listen to everything that you say, and it affects the outcome of what we write.” But then that would suggest that we don’t have a plan and everything that we’re doing is like the band that finishes a song and asks, “What do you want us to play next?” But we have a set list, so you can’t win. And I will just say, having experienced the intensity of the fandom, for all of the wonder and fantastic feeling that it brings — and also all of the terror of Oh my God, they’re going to hate us if we do this — it is rarefied, special air. And I wouldn’t trade it for the world.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

More From Into It

- Britney Was Always Trying to Tell Us Who She Was

- If Hollywood Hates Long Movies, Why Does It Keep Making Them?

- What Will It Take for Celebrities to Throw Out the Legacy PR Playbook?