Even a brief association with SNL can drive success — the infamous list of failed one-season performers who became comedy superstars includes Sarah Silverman, Ben Stiller, Tim Robinson, and more. But appearing on SNL was not always a comedy event, and throughout the show’s history, what has constituted being an official “featured player” has been a bit muddled. In 1981, Emily Prager was credited despite never appearing in an episode. Laurie Metcalf is also canon for her single prerecorded “Weekend Update” segment in the same episode. The first Black female cast member on SNL, Yvonne Hudson, was an uncredited extra for several episodes in 1978 before she received her title card during the opening montage.

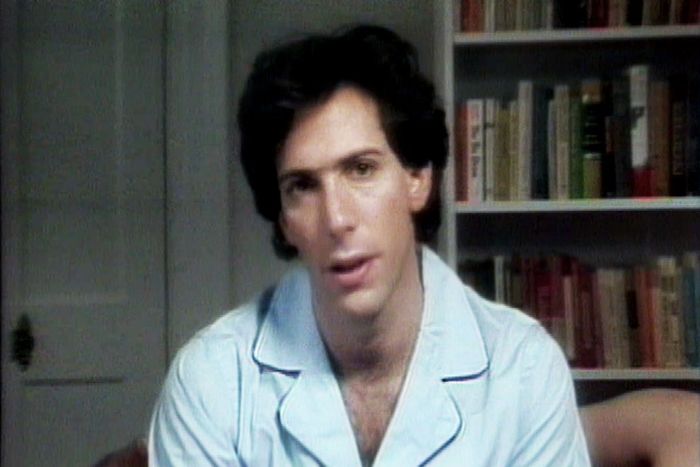

That brings us to the curious case of Mitchell Kriegman. Nineties kids might know his name from a litany of iconic shows during Nickelodeon’s heyday, most notably as the creator of Clarissa Explains It All. But before that, Kriegman was a young video and performance artist in Soho when he was asked by Michael O’Donoghue to join his 1979 SNL spin-off, Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video. That experience led to a brief, harrowing stint as a writer, filmmaker, and onscreen performer during SNL’s sixth season in 1980. Despite several appearances on-air during the first half of the season, Kriegman has never been considered part of the official cast.

Kriegman provides a firsthand account of one of SNL’s most disastrous chapters, during which he witnessed the failed auditions of several future stars, and describes being fired during “Weekend Update” while his parents sat in the live audience. His story highlights a gap for many show historians and makes a strong case for why he should be belatedly recognized as a card-carrying member in the illustrious club of comedy legends and quirky lesser-knowns who have passed through Studio 8H.

SNL’s first head writer Michael O’Donoghue recommended you to Jean Doumanian for season six. How did that relationship begin?

I was in Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video. It was Emily Prager and Michael O’Donoghue basically producing what was, to my understanding, the replacement for SNL, once Lorne decided he didn’t want to do it anymore and everyone got burnt out. They did a search for all these short pieces, and I was one of the lucky guys they picked. Anything short and weird, they wanted; I fit the category. They took three of my pieces for Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video. They ended up not airing it but put it in movie theaters.

It was O’Donoghue’s treatise on how to upset the censor, his big enemy at the time. He was a role model to me. I loved how contrary he was. He used to say, “If you’ve hired me, you know you have a problem.”

I was not that interested in SNL. It was not as “cool” as what I was doing. To me, SNL was showbiz, standard fare. I knew some of the people there — Hal Willner and Cabot McMullen, who was a set designer. I worked with him a lot. I remember meeting Belushi backstage, who acted like your normal bully. I was writing in a notebook and he grabbed it and threw it in the trash, like some guy on the football field would do.

What was your relationship with Jean Doumanian like initially on the show?

I saw myself as an outsider. I wasn’t an aspiring writer who wanted to write comedy. I’m just a guy saying, “I’m going to do my crazy stuff on the show.” And Jean, whoever her sources were, thought I was going to be a big deal — she was wrong, obviously. She gave me the best office, Tom Schiller’s beautiful corner office, which I adored. I had a deal to make little films, write sketches, and I was a featured performer, briefly. She saw me as an avant-garde Woody Allen. I became someone she brought into auditions and special meetings in her gorgeously designed dark office. She asked my advice on a lot of stuff. I don’t think she ever followed it.

She brought me in one day with Andy Kaufman. He pitched a weekly video, every episode. She turned him down! He was a big deal already.

You mentioned Woody Allen, who was close with Jean. Any truth to the rumors he was involved in season six?

Letty Aronson is his sister. She was on staff and was definitely involved with casting with Jean and Mike [Zannella, SNL talent coordinator]. But off-screen, you did get little appearances of Woody Allen. One meeting with Jean, the phone rang. She picked it up and said, “It’s Woody,” whispering and pointing into the phone. That meant I had to leave.

Woody Allen was never current for SNL, even when he was in his heyday and funny. By then he had already become a “serious filmmaker” with Interiors in ’78 — it was dreadful, and he disavowed comedy. He was old-school hip in the days of Nichols and May but not Gilda. I think this Woody Allen–Jean Doumanian group — Zannella, Letty, Mason Williams — really represented old-school showbiz. Mike Zannela had been a talent coordinator on The Johnny Carson Show — very prime time. He was Jean’s Jean, who had casted for Lorne. That might’ve been the reason so many of the casting decisions were so poor. Even Ebersol had trouble replicating the Lorne Michaels New York City–Toronto vibe.

You were an eyewitness to the cast-audition process that year. Were there any notable omissions?

I was in shock every time there was an audition. The people I thought were unbelievable, and who were later proven to be unbelievable, were overlooked. Paul Reubens came in with a rack of costumes. He tried on each one and would do the character. They were all characters that became Pee-wee’s Playhouse, so that was already there in his head. They passed on Paul.

There was a guy named Mark King — he did eventually appear a couple of times on SNL. He was hilarious, a Robin Williams type of character. They passed on him.

Marjorie Gross was a pretty well-known stand-up who was best friends with Sandra Bernhard. They came in together into Jean’s office and did a shtick and were both hilarious and weird and different. Jean passed on them.

Another person who was amazing was Mercedes Ruehl. In those days, she did an intense one-woman show. It was brilliant. It would’ve been like hiring the new Lily Tomlin! I talked to her later — she said she was so devastated by being passed over by SNL that she moved to Colorado and thought she was going to stop being in the business.

Instead of all these brilliant people, they made all the wrong choices. Jean thought she was brilliant, had picked all the right people.

When did you see Eddie Murphy?

The first time I saw Eddie, he showed up and was talking to Yvonne [Hudson], the receptionist, who went on to be a bit player briefly. She was cool and the only other Black person there. Eddie hung out with her at the front desk a whole bunch.

In a disastrous situation, Eddie was better than the game. He came in 100 percent knowing what he was dealing with. He had that goofy laugh that made him get through every stupid, awkward, strange conversation with Joe Piscopo. It was a chess game to Eddie, you could see — he was willing to work with anybody who was going to move the ball forward. He could make things funny that weren’t at all, because that’s what you had to do to succeed in that environment.

When did things begin to disintegrate?

There were two kinds of comedy at SNL: There was Father Guido Sarducci and O’Donoghue — off-the-wall, doing something on the street, original and wild, that fits no form. Then you have “Bass-O-Matic” and the parodies. By the time I hit SNL, they were basically only doing parodies. So I had no place. I wanted to do things like “Who Is Watching Now?” and go with a crew around the country literally to find someone who was watching the show. I wanted to do “The Topo Gigio Story.” All this other crazy stuff — stuff that kind of went to Letterman. It bifurcated into SNL parodies and Letterman-cool, oddball stuff.

Jean had this terrible management idea where you bring your troops into your office and read your reviews to them, even if they’re bad. It was just a downer. I think the cast felt sad and punished. I can’t imagine they didn’t feel humiliated. It was a stupid idea.

We’re sitting in there, and she reads the [Newsday critic] Marvin Kitman review, which said I was a grasshopper among worms, a scholar among morons. I’ll never forget, Joe Piscopo was sitting right behind me. He says, “I didn’t hear anyone laugh at that.” [Laughs.] That was the mentality. The week before I got fired, everyone stopped talking to me. It was not glamorous. It was kind of lame!

You contributed three short films during your tenure — Dancing Man, Heart to Heart, and Someone Is Hiding in My Apartment. Did you write live sketches as well?

Nothing was ever accepted except for one sketch I did. I wrote up a ton and doubled down even when it was clear to me that the writing was on the wall. I had one sketch called “Dying to Be Heard.” It was a good, solid sketch. I had to do the “game-show thing,” and I wasn’t into that. It was about all these terrible stories of feminist poets who became famous after they killed themselves. I came up with the idea that the game was you read your poetry and committed suicide, then they picked the winner. It was dark.

I got fired during the Carradine show. “Dying to Be Heard” was the show before I got fired. Which is funny: I was fired after getting a sketch on, then I was in a film the day I got fired.

Did Jean tell you the news?

Oh, yeah, it was great. I wanted to quit anyway, but couldn’t. The hilarious thing was it was the Christmas show, and my parents came. They thought it was a big deal I was on Saturday Night Live. And I would tell them how horrible it was and how much I didn’t like it. They saw the show and in fact sat next to John Carradine, the host David Carradine’s father. I was a zombie. I knew around Malcolm McDowell that I was gone because the talent coordinator, Neil Levy, stopped talking to me — he was definitely a company man. I was just walking through the paces, trying to not get in trouble, being friendly, hanging out with Hal Willner.

During “Weekend Update,” someone came to me and told me I have to see Jean. Literally, while “Weekend Update” is being performed, I go to her office and I get “my update.” [Laughs.] And my update is: “This isn’t working out.” I had rehearsed how I would respond because I didn’t want her to change her mind. I wasn’t unhappy about it. I met my parents, who had gone to the Rainbow Room. There’s my mother: “Oh, it wasn’t so bad. We saw you in the film, you were so great.” I said, “It’s okay mom, I just got fired.” And she burst into tears.

It not being the right fit aside, was there anything specific that led to Jean firing you?

I got fired because of somebody else. There was a writer who was talking to the press. Jean had terrible press. This writer knew Variety, all the showbiz writers in town. I was very good friends with this writer, who was spilling the beans on all the backstage stories. It was one of those things where your friends are drinking in the dormitory and don’t get caught, but you do and you’re supposed to snitch on them.

I’ll tell you the most horrendous Saturday Night Live story I have, which exemplifies why I was such a square peg in a round hole. My comedy was me being clueless as a person, making mistakes. It was the first day I was there. I was in Brian Doyle-Murray’s office, and a bunch of writers — all male, pretty much — were in the room, trying to one-up each other with one-liners and jokes. I did not really know how to write a joke. I see on the desk a pile of white powder. It was a really big pile. I thought, This is too cliché. It can’t really be coke. They don’t really sit here and do cocaine all day.

Everyone’s being really funny, and I’m not fitting in at all. I see on the ceiling they have some of that asbestos tile, and I thought maybe some fell down on the desk. I look and decide to make a joke: “Look! Cocaine!” And I blew it all away. Brian leapt across his desk and started strangling me. That gives you an idea of what a bad fit I was — or I had a brilliant new way of doing things.

Your screentime surpasses that of several officially credited featured players, including Laurie Metcalf, but you aren’t acknowledged by the SNL overlords as part of the cast pantheon. Should you be counted as an official cast member by the show?

Well, yeah. They did a picture, my cast photo! I’m eating an ice-cream bar against a wall. I did the films. I was there! There’s no doubt about it. I don’t know if it was a little bit of malice on Jean’s part to erase me. [Laughs.] But that’s part of the experience. It was all such a mess. We’re not just talking about bad choices. We’re talking about poor organization, poor management.

You’ve gone on to be a creator and showrunner yourself, including Clarissa Explains It All. How did your experience at SNL inform that? What did you learn professionally from Jean as a boss?

… Long silence. I think it’s described as “crickets.” I learned how much I didn’t like that kind of craven, ambitious showbiz where people were trying to get ahead rather than have a good idea.

Here’s a lesson: There was a guy, the visual artist Teddy Dibble, that I worked with. Really brilliant, really funny. A little Belushi-like. That was cool comedy. I suggested at some point to bring in Teddy Dibble, showed them his work. They said: “We hired you to rip off people like this.” I thought, Wow, that’s really saying the quiet part out loud. And not something I’m into.

It was a crass crowd. They’re not the people that you’d invite to Balthazar for dinner. Jean had some idea about doing stupid comedy — her line was always, “Now that’s funny!” But she never laughed. She would never spontaneously laugh. She was in over her head.