In 1990, 25-year-old Janeane Garofalo moved to Los Angeles for the same reason people have been moving to Los Angeles for the better part of a century: She had a moderate level of ambition and a business card handed to her by a talent manager who’d seen her perform. “He said he worked in L.A. with some comics and if I came there to give him a call,” she says. “And because I was so naïve, I believed that you just did that.”

Garofalo had started doing stand-up about five years earlier, mostly in Boston, where she quickly developed her own idiosyncratic style onstage: She told long, winding, often self-deprecating stories plucked from her life, spiked with wry commentary on pop culture. What she didn’t do is tell jokes.

“I have never been a strong joke writer,” Garofalo says. “I stand onstage and it’s almost like a filibuster, because I’m just talking and talking and talking and hoping that people will find it funny.” Some did, but once she got to L.A., very few of those people seemed to go to comedy clubs.

The city’s stand-up scene was dominated by three big venues: the Comedy Store, the Improv, and the Laugh Factory. Garofalo bombed at all of them. It took her ten tries before the Improv “passed” her, the holy imprimatur required before she could perform in regular slots there. “And the only reason I passed at all is because Dennis Miller said, ‘Jesus, take pity on her,’” she recalls. It was even worse at the Comedy Store. “Mitzi Shore said to me, ‘You’ve got a lot of attitude, kid, and no talent to back it up,’” she says of the club’s legendarily cantankerous owner.

The one solace Garofalo could take from her rough treatment was that few of her friends were faring any better. Practically upon arrival in L.A., Garofalo had become a central figure within a growing community of young comics there. “She was the hipster girl that everybody loved,” says Margaret Cho, who moved to L.A. from San Francisco in 1991 at Garofalo’s urging. “She made us all listen to the Replacements, and was changing us all up style-wise. We all cut our hair, and started wearing Doc Martens and athleisure. She was the first person to wear athleisure.”

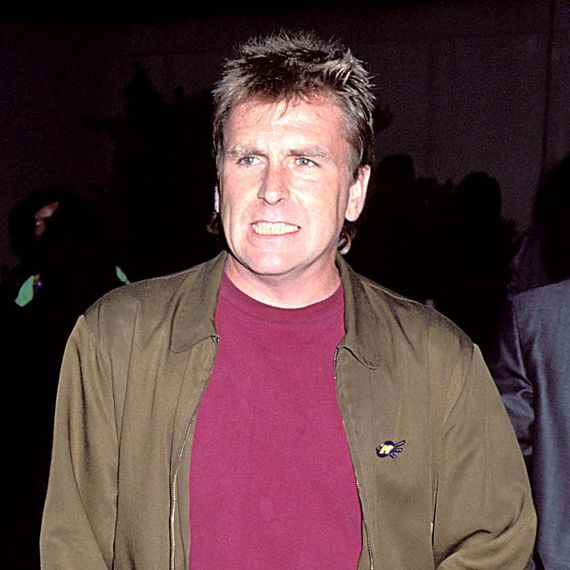

Bob Odenkirk, whom Garofalo had met a few years earlier in New York when she first auditioned for Saturday Night Live — “I tanked that too,” she says — had started coming out to L.A. around 1990 to visit and would try his luck onstage at the Improv and the Comedy Store. “I failed miserably,” Odenkirk says.

Colin Quinn had a steady gig on MTV’s game show Remote Control in the late ‘80s, which helped get him in the door at a lot of clubs, but didn’t help much after that. “I had my little MTV fame but I still fucking bombed,” he says. “I wasn’t an act you would rely on to rock the house, to put it mildly. I could easily go in the toilet in two seconds, and it happened very often.”

It was a strange time to be a stand-up. Comedy had become a booming industry in the ‘80s, and as clubs spread like wildfire across the country, they needed comics to fill them. As a result, even many relatively green performers could make a living on the road. Television offered further opportunities even beyond the usual coveted spots on the networks’ late-night shows, as showcases like A&E’s Evening at the Improv, VH1’s Standup Spotlight, and HBO’s Comedy Hour sprung up. But by the late ‘80s, it had all started to curdle. The stand-up circuit was awash in cocaine and testosterone. Originality wasn’t valued. Comics knew what their audiences wanted, and most simply delivered exactly that. Think white dudes in dark blazers with the sleeves rolled up standing in front of brick walls telling jokes about taxi drivers who don’t speak English and women who take too long in the bathroom.

“This is at the point of putrescence of the ‘80s comedy boom,” says Dana Gould, who let Garofalo sleep on his couch when she first moved to L.A. “Comedy had been so whored out that comedy fans didn’t go to comedy clubs anymore.” Instead, places like the Comedy Store and the Improv became stops for tour buses filled with sightseers, or bachelorette parties looking for something fun to do after tequila shooters at the Hard Rock Cafe.

“The audience had been groomed by the stand-up boom to expect a certain kind of comic, and they really just wanted that and nothing else. So for a lot of us, those clubs were just so unwelcoming,” says Odenkirk. “I always wanted to immediately apologize to the audience and say, ‘I can see by your faces that you wanted something different. I know I’m not what you’re looking for. I’m sorry I started speaking into a microphone.’”

Kathy Griffin recalls bombing during her three-minute audition at the Improv around 1989 and being told by another comic that she needed to make sure she was getting a laugh every seven seconds. The club’s booker hounded her to fit in, to follow the example of other comics at the club, to make her sets more like theirs. “I knew my flow was different,” she says.

Largely shut out from the L.A. clubs, this group of comics needed a stage where they could be different. What they found was not exactly a stage, but a bit of floor space in the small upstairs loft at Big & Tall Books, an indie bookstore and café in West Hollywood. On Tuesday, August 6, 1991, Garofalo — with some help from Quinn, Gould, and an actor named Alan Gelfant — organized a low-key show there.

The night hardly seemed momentous at the time. Quinn recalls seeing Andy Dick and Dino Stamatopoulos performing their masochistic take on Abbott and Costello’s classic “Who’s on First?” but few remember much else about the evening, beyond that there were few there to do the remembering. Maybe a dozen people showed up, including the performers. Still, the next week, they came back and did it again.

The shows at Big & Tall would soon move to Wednesday nights, and then run, not quite regularly, for nearly a year, into July of 1992, but they rarely drew more than 20 or 30 brave souls into that loft space. But those who turned up saw something they couldn’t see anywhere else. While comedy clubs across the country were filled with stand-ups trying to hone their best cracks about airline food and the differences between men and women into a polished set fit for The Tonight Show, the performers at Big & Tall were experimenting with odd, conceptual bits, strange characters, or simply spinning the emotional roller coaster of their daily lives into comic riffs. “Some of it was a reaction against that early ‘90s, very slick, gymnastic kind of comedy,” says Quinn. “It was very informal, just people up there playing around with the form.”

Among the people up there were a roll call of future stars: Quinn, Garofalo, Gould, Odenkirk, Griffin, Cho, Dick, Ben Stiller, David Cross, Andy Kindler. Most of these comics were in their mid-to-late 20s then, and were struggling to get on at the big L.A. clubs. They were just looking for a place to make each other laugh. But among the bookshelves, over the din of the cappuccino maker, what would soon be called “alternative comedy” was taking its first tentative steps into the world.

“I think it did start with Big & Tall,” says Odenkirk. “It just felt like a bookstore, late at night, yeah, that makes sense. People are kind of in a thinky headspace compared to a drinky headspace at the Improv or whatever. They’ll listen to your meandering, random comic thoughts. It was very welcoming and forgiving. These were like the demo tapes by this group of performers.”

It was a brief moment in time. By the fall of ‘92, many of the bookstore’s main players were starring or writing for The Ben Stiller Show. Shows began popping up at other offbeat locales, including Beth Lapides’s UnCabaret, which opened at a supper club called Luna Park in 1993 and quickly established itself as the alt-comedy scene’s creative locus. A few years later, Mr. Show became a showcase for the offbeat sensibility that first began to form at Big & Tall. Not long after that, the entire comedy world seemed to be bending in that direction.

This alternative movement would help revive comedy over the next couple of decades, in part by building an audience for the kind of genuine emotional vulnerability and sharp, knowing absurdism that had nearly been lost during the ‘80s boom. It also foregrounded the experiences of women, both as comics and as organizers, in a way that was rare during an era when comedy was dominated by the chest-thumping machismo of guys like Eddie Murphy, Andrew Dice Clay, and Sam Kinison. But Garofalo — who is as self-deprecating offstage as she is on it — scoffs at the notion that there was any grand plan for world domination back then at Big & Tall.

“We were doing it because a lot of us couldn’t get stage time,” she says. “At the time, I thought of it more as a failure of my own. It didn’t occur to me, like, ‘Let’s start a new movement!’”

Big & Tall Books no longer exists, and it hasn’t for a while. It used to occupy a slim, two-story storefront at 7311 Beverly Boulevard, a couple blocks from the New Beverly Cinema, an historic art-house theater. Today, it’s a sleek-looking sushi bar and ramen house.

In the early ‘90s, lots of young comics already lived nearby. The neighborhood was dotted with hipster coffee shops like Java, Highland Grounds, and Ministry, as well as a couple of bars, including a place called Fellini’s, where, if you knew the secret knock, you could come in and drink after-hours. Rents in the area were also still cheap enough that a few struggling comics or actors living together could pool their resources and just about make it work. Garofalo shared a place with Jeff Garlin less than a mile from where Big & Tall opened in 1991. Later she’d move into a nearby house on Curson Avenue that became a crash pad for a rotating cast of comedy strivers that at one time or another included Cho, Greg Behrendt, Laura Kightlinger, and Jack Black. Odenkirk lived a few streets over. Stiller had an apartment with his then-comedy partner Jeff Kahn on the corner of La Brea and Hollywood Boulevard.

“Comedians are pretty tribal, and we were all sort of loafing,” says Cho. “Janeane was a hub. She’d always have somebody with her, some comic from New York or Boston, hanging out. You’d go meet her at the Beverly Connection Starbucks, and we’d sit there and collect people. She was the first person who told me what Starbucks was.”

In 1991, one of the co-owners of Java opened Big & Tall across the street. The new bookstore quickly cultivated a decidedly bohemian vibe. Customers lounged around on mismatched furniture, sipping coffee, huddled over books by authors like Charles Bukowski and James Ellroy. Dudes in trench coats browsed racks of underground comic books. Prominent shelf space was reserved for titles by independent publishing houses like Feral Press and Semiotext(e). “Big & Tall became the coolest thing in that part of Hollywood,” says Alan Gelfant, an actor who had been a manager at Java before taking up the same position at Big & Tall.

Toward the back of the store was a staircase that led to a small second-floor loft. Up there were a handful of tables and chairs, and a big window that looked out across the street onto El Coyote, an iconic local Mexican joint.

“I’d go up there, drink coffee, smoke cigarettes, and watch people steal books,” says Gelfant. “But it never really got used that much.” Gelfant had become friendly with Quinn when he was emceeing a comedy night in the West Village in New York City in the mid-‘80s. In L.A., Quinn introduced Gelfant to Garofalo, who first suggested performing in that upstairs loft.

“Moon Zappa and I wanted to try to do that even before Big & Tall,” Garofalo says. “We’d talk about it and didn’t know how. It was really myself, Dana, and Colin, asking around places, ‘Can we do stand-up here?’”

Gelfant says Big & Tall’s owners were “up for anything,” and gave them pretty much free reign to do whatever they wanted in that upstairs space.

“It was Janeane’s brainchild,” says Quinn. “She made it happen.”

As Gould recalls, “You’d go to the Improv and try out new stuff and they’d say, ‘What the fuck were you doing? You bombed! Jim McCauley, the Tonight Show booker, was in the audience!’ Janeane was like, ‘Where can we go and bomb if we want to?’ She had the idea to do a show at Big & Tall.” He says his main contribution was to name that very first show. “I’m famous for the worst titles. It was called Cirque du Stress. C-I-R-Q-U-E D-U … See, if I have to spell it, it’s a fucking terrible title. The name lasted one show.”

That first show at Big & Tall did not exactly set the entertainment world alight, but it was a start. “It immediately clicked because it was like, ‘Hey, nobody sucked,’” says Gould. For comedians frustrated by the strictures of comedy clubs, the shows at Big & Tall became a beacon.

Michael Rowe was a struggling comedy writer then who’d felt so dismayed by his experiences as a stand-up in L.A. that he’d quit performing entirely. But Garofalo lured him to Big & Tall. “She said, ‘It’s not stand-up. Just do any stupid thing you ever thought of,’” says Rowe, who’d later write for Coach, Futurama, and Family Guy. He recalls accompanying her to Big & Tall one night, and seeing a brightly lit bookstore with people sipping coffee and studying. “I’m like, ‘There’s no microphone? There’s no stage?’ And she’s like, ‘No, just watch.’ Then she just goes to one end of the room and starts talking, like, ‘Hello, everybody!’ Then they’d slowly engage. People would come from downstairs and watch.”

Thirty-year-old Kathy Griffin was already part of the famed L.A. comedy troupe the Groundlings then, but was struggling to distinguish herself. Playing a character in a sketch or shoehorning her personality into an improv didn’t suit her, but her attempts to develop a stand-up act were stymied by club owners and audiences who didn’t know what to make of the uncomfortably personal, self-lacerating tales she liked to tell onstage. Fellow Groundling Judy Toll introduced her to Garofalo. “Janeane said this great thing: ‘Kathleen, you don’t care what the audience thinks, do you?’” Griffin recalls. “What she meant was follow your gut. Do what you think is funny. Keep doing it until you figure out a way the audience will get it.” Griffin became a Big & Tall regular.

David Cross was still living in Boston at the time, but during visits to L.A., he’d often crash on Garofalo’s couch and do sets at Big & Tall. “Before anybody knew who I was, my act was quite a bit different,” he says. “I was able to get away with opening with fake characters or saying something that was purposely confusing. There was a little more theatricality to it.”

In one of Cross’s bits from that era, he’d ask the audience, “I wonder what it would be like if Jack Nicholson was your dentist?” As the crowd waited for him to bust out a Nicholson impression, Cross would stand there, rubbing his chin, for 30 seconds to a minute, looking into the distance, and then say, “Yeah, I wonder what that would look like.” It was essentially a joke about telling jokes, a nod and a wink to audience members savvy enough to get it.

During one of Cross’s L.A. visits, Garofalo introduced him to his future Mr. Show collaborator. Or tried to. “Bob played basketball on Sundays with Adam [Sandler] and Conan [O’Brien], and Dave wanted to play,” Garofalo recalls. “So I brought Dave to Bob’s house.”

Garofalo had told Cross all about her “funny friend Bob” and figured they’d hit it off. But when they arrived, Odenkirk was deeply engaged in other activities. “He was watching TV and eating a sandwich,” says Cross. “The screen door was open. He wouldn’t even come to the door. He wouldn’t even say, ‘Hi.’”

Odenkirk admits he was rude, but says it wasn’t anything against Cross personally. “I ignored both of them wholly and completely.”

The shows at Big & Tall reflected the store’s vibe. It was informal to a fault. There was no cover charge, no tickets, and comics didn’t get paid. Promotion was done by word-of-mouth and the odd homemade handout. “Dana was really good at making flyers at Kinko’s, which would superimpose our heads over famous historical photos,” says Garofalo. The lineup was determined largely by whoever was around and wanted to go up. It only took about 25 people to make that loft feel crowded.

“We’d have people standing on the stairs looking up,” says Gould. “You were right on top of the audience. It was as intimate as you could get while dressed. There was no line between the stage and the performer. There’s a famous photo of Jack Kerouac, reading a poem at a beatnik coffee shop, using a small step ladder as a table. That’s what Big & Tall was like.” A particular performance style began to emerge. “Because everybody procrastinated, everybody wrote their material that day. That was the genesis of taking your notebook onstage with you. It was because you didn’t know the stuff. You’d just written it.”

Odenkirk points out that Richard Lewis “famously preceded all of us, going onstage with a notepad, but Janeane was just built for that. She was sort of our guiding light. I loved it right away. I could do what I considered stand-up, which for me was reading my notes for possible comedy ideas.”

Garofalo was one of a cohort of comics who blossomed in the low-stakes environment. “What I loved about Janeane was that she’d just talk about what happened to her that day,” says Jeff Kahn, who went on to co-create The Ben Stiller Show. “And Dana would kill me. His comedy was all about himself and his family. It was honest and raw yet absolutely universal at the same time.”

Club comics often compared themselves to gladiators armed for battle when they took the stage, but at Big & Tall, sensitivity and open-mindedness were more likely to be rewarded than cutting one-liners. “It became a storyteller show,” says Gould. “That’s where I was forced to discover my stand-up style by having to turn to stories and bits. Kathy Griffin perfected that more than anybody. Seeing Kathy onstage at Big & Tall was like when you have a goldfish in a little sandwich bag then pour it into the aquarium and it just takes off.”

Not every comic who flourished at Big & Tall followed the same formula. “Andy Dick had some of the best sets I’ve ever seen,” says Andy Kindler. “He’s just amazing talking about his life. And with him it was dangerous.”

At the time, Dick was a startlingly original, if still sometimes disturbing, comic voice. He occasionally did short monologues drawn from his life, but often his experimental approach seemed designed as much to shock and appall the audience as to make them laugh. “What I did onstage then is the same thing I do now, very Andy Kaufman-esque performance art,” says Dick. “I wasn’t known yet, so I could really fuck with people. I did some things that really were fucked up, like pretend I was mentally retarded trying to do comedy. Or I’d be a bad magician. I tried to make a straw disappear in my nose, and crammed it up there. My nose started bleeding profusely onstage. It was bad for me but funny.” By the late ‘90s, Dick’s troubling record of drug arrests and repeated sexual misconduct — including multiple reports of him groping people against their will and exposing himself in public — would begin to overshadow his comedy, but back in the Big & Tall days, his willfully offensive jags were largely tolerated when they seemed part of a sincere quest for irreverent laughs.

“Andy was pretty much the same as he’s always been, maybe on less alcohol,” says Gelfant. “But he was always obnoxious.”

Soon, a set of unwritten rules developed among these comics. “We had a no-hack rule,” says Griffin. “You kind of weren’t allowed to repeat any material. Sometimes we were okay with telling a story or doing material that maybe didn’t elicit a laugh but felt personal and real. Bombing was one thing, but it was almost like the audience let you have slack because they knew you were trying to be different and give them something genuine.”

Some comics adhered to this code more religiously than others, but what all of them were reaching for was something that re-created onstage the conversations and intimate moments they had between each other every day. There was an aspiration toward less polish, less professionalism, less of everything that felt like mainstream comedy. Disdain was often heaped on traditional stand-ups with well-rehearsed acts.

“The irony is that, of course, everyone has an act,” says Greg Behrendt, who eventually worked on Sex and the City and wrote the book He’s Just Not That Into You. “Janeane going up there with her notes is an act. David Cross talking as a southerner for 15 minutes before letting go of that premise is an act. But it was original and different.”

Not every show at Big & Tall was a revelation. Sometimes experiments failed. Sometimes audiences were more interested in their coffee and their Kerouac than in seeing comedy. But good or bad, the shows at Big & Tall always felt gleefully unpredictable. One night, a woman in a flowing red dress stood up to perform, as two men flanked her, holding the sides of her dress. As she began talking about how men objectify women, she also began twirling, slowly unraveling her dress. “I was sitting there with Moon Zappa and Ben Stiller, watching,” says Rowe. “As this woman continued to talk about how men objectified women, she’s revealing herself. Then, she’s standing there completely naked. I looked at Moon and she just said, ‘Nice tits.’”

Even when they weren’t performing, this was a group of comics who hung out together, drank together, partied together, slept together, and lived together. Some even started referring to them, slightly tongue-in-cheek, as The Posse. “We traveled in a weird little pack, as everybody does at that age,” says Gould.

Most of the comics drank socially, and occasionally to excess, but unlike many other comedy scenes, drugs weren’t central to it. “There was a weird absence of drugs during that time,” says Laura Milligan, a comic and actress who performed at Big & Tall. “It was right after that whole ‘80s everybody-doing-blow thing. We’d make fun of anyone doing coke.”

Milligan, Rowe, and a young talent manager named Dave Rath — who’d previously been a doorman at the Improv — were among those who hosted frequent house parties for this rotating circle of creatives, which at times included Quentin Tarantino, Maynard James Keenan, Moon Zappa, and Kim Deal. “We all kind of dated Quentin,” says Griffin. “He was kind of a whore. I say that with love.”

The onus to be constantly funny kept performers sharp. “That peer pressure that group put on me was a fucking godsend,” says Griffin. “You couldn’t bring hack to the table and think you were going to hang with this group or survive socially. Everybody was working their muscle, trying new shit all the time.” They also were constantly talking shop, discussing ideas, or offering tags to jokes.

“That’s a friendly, generous thing comedians always do in a way to get to know each other,” says Cho. “It’s also very subtle one-upsmanship. You’re always trying to best each other with tags.” The fact that women were so central to this scene helped to dial down the testosterone. “Comedy in general is such a boys’ club,” says Cho. “But in alternative comedy you were seeing women so much more; we were creating for women, and so I think it avoided that.”

At parties, bars, and restaurants, useful connections were being forged among these comics. Gould knew Judd Apatow from performing at the Improv, where Apatow often emceed. “I took Judd to a party at Ben’s apartment, and Judd and Ben really hit it off,” he says. Apatow soon began working with Stiller and Jeff Kahn on developing The Ben Stiller Show. When it debuted on Fox in the fall of 1992, the cast and writing staff were dominated by Big & Tall alums including Garofalo, Odenkirk, Dick, Gould, Stamatopoulos, and Cross (who joined midseason). “Judd met Ben, and six weeks later, he was my boss,” says Gould.

Although the comics were ambitious, the scene rarely felt cutthroat. At the time, few of these comics had much going on in their careers, so envy wasn’t a big problem. “We were basically doing shows with our friends, for our friends, and that was it,” says Cross. “Nobody was trying to get famous or pitch themselves as a comic actor through their stand-up or sketches. There was none of this, ‘Hey, there might be a talent scout from UTA! We all better do a good job!’ It was devoid of any kind of ego or machinations. It was very nurturing. Everybody was doing it for the love and the art of it.”

The term “alternative comedy” wasn’t much used during the Big & Tall era. “None of us referred to ourselves as ‘alternative comics,’” says Garofalo. The moniker would grow more widespread by the mid-’90s but evolved into a slightly anguished term. Mainstream comics derided it as an excuse not to have to get laughs or to face stand-up’s unforgiving gauntlet. But time has taken some of the sting out of this turf war.

“Now it seems so dated: ‘alternative comedy,’ ‘the Posse.’ It’s like, ‘Okay, Boomer!’” says Griffin. “The truth is, good shit is good shit.”

Big & Tall wasn’t built to last. No one remembers exactly how many Wednesday nights comedians filled that upstairs loft, but almost certainly by the end of the summer of 1992, the shows were a thing of the past. Garofalo, who’s steadfastly uncomfortable taking credit for Big & Tall’s impact, doesn’t recall its end but is quick to blame herself. “I don’t have a great work ethic,” she says. “I’m sort of like, ‘Oh, this isn’t working. There’s not a lot of people coming. See ya.’ I’m what you call a real quitter.”

In fact, there was no epic collapse, no dramatic exit, just a gradual petering out. A bevy of the bookstore regulars began working on The Ben Stiller Show, which premiered that September. Garofalo also scored a role on Garry Shandling’s late-show satire, The Larry Sanders Show, which debuted in August. And more alt-comedy shows started popping up at coffee shops, bookstores, night clubs, theaters, and restaurants, places like the Diamond Club, Pedro’s Grill, the Onyx cafe, Largo, Highland Grounds, the Upfront Theater, and even at Borders bookstores.

Perhaps the biggest inheritor of Big & Tall’s mojo was UnCabaret, a show first organized by Beth Lapides, to be, in her words, “un-misogynistic, un-homophobic, un-xenophobic.” UnCabaret had been kicking around for a few years in different locations before finding a new home base in 1993. “When UnCab moved to Luna Park in West Hollywood on Sunday nights, that was the place,” says Gould. “That was The Ed Sullivan Show of the alt-comedy scene.”

Big & Tall had served a purpose, but alt-comedy outgrew it. “There were other places more conducive to audiences,” says Gelfant. “In a club, people usually shut up when you’re there. Big & Tall always had a bit of plonking around, people just running in and out, people who didn’t know or care.”

Assessing influence can be tricky. To say alternative comedy began in any one room is to invite an endless stream of very valid arguments, but Big & Tall was very much the right place at the right time. At the very least, an important idea took root there. And that idea was that comedy could be so much more than it had been. It didn’t need to follow the setup–punchline format, it didn’t need to be tight and polished, it didn’t need to be dressed in a blazer with the sleeves rolled up, and it didn’t need to take place in a dark club with a two-drink minimum. Moreover, comedy didn’t have to be sweaty bloodsport. Its emotional palette could go beyond anger and insecurity. Yes, people like Andy Kaufman, Albert Brooks, Lenny Bruce, and Jonathan Winters certainly had hinted at this long before any comics climbed the stairs to that bookstore loft, but if nothing else, Big & Tall was proof of concept.

“It was very much a beginning,” says Odenkirk. “It wasn’t a movement yet. It was years away from being a movement. UnCabaret was where it was like, ‘There’s something really valuable here. This isn’t just a bunch of misfit toys from the main scene.’ Big & Tall was just a weird start.

“If you look at what we were doing then, where you’d see it now is in podcasting,” he continues. “It started this raw, off-the-cuff comic riffing and interacting, and this expectation of an audience that was listening.”

The mainstream success of Big & Tall vets like Odenkirk, Cross, Stiller, Garofalo, and Griffin, as well as the adjacent careers of their peers in this L.A. scene such as Patton Oswalt, Zach Galifinakis, Jeff Garlin, Judd Apatow, Will Ferrell, and Jack Black, is evidence of how much this alternative movement changed comedy. “What happened was the mainstream came our way,” says Garlin. “You had people getting jobs who were in our audience. They got into positions of power; next thing you know, we’re on Letterman.”

Dave Rath, who was a junior manager back when he was showing up at Big & Tall to watch his friends perform, now runs his own management company with a client list that includes Oswalt, Brian Posehn, and Pete Holmes. Another former Big & Tall attendee, Naomi Yomtov, was a 26-year-old assistant at the William Morris Agency back then. She later married Odenkirk and became a talent manager for, among others, Jenna Fischer, Kristen Wiig, and Bill Hader.

“Being around comedy so much, I got tired of the energy behind the setup–punch line and how the audience needs to have a certain number of laughs to feel like the comic is any good,” she says. “At Big & Tall, they had great faith in the audiences to follow along. They were storytellers sharing about themselves in a way that has become really popular in the intervening years.”

Cross points out that what was going on in comedy at that point wasn’t limited to L.A. There were exciting scenes in San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, New York, and other places, too. But many of the most interesting people from all those places were drawn together in L.A., if for no other reason than because that’s where the entertainment business was. “So it seemed extra special,” he says. It’s not unlike the places other historic artistic endeavors sprung up. “All those important scenes, we look back and go, ‘Man, it must’ve been cool to hang out with those folks as they were creating in Topanga Canyon or the Lower East Side or wherever,’” he says. “Yeah, it was.”

As Gould puts it, “It was the only time in my life I was part of the cool kids.”