After 12 films, it’s abundantly clear that there are certain things that Hayao Miyazaki really loves. Airplanes! Nature! Capable, hardworking young women! Japan, but also a lot of European aesthetics! The animation legend’s latest movie, The Boy and the Heron, is full of almost all of Miyazaki’s go-to motifs, making it a veritable Easter egg hunt of references and thematic connections to his past work in addition to being one of the most impressive and moving films of the year.

One of the things that Miyazaki loves, and that he returns to in The Boy and the Heron, is a bunch of weird little guys. The warawara might be Miyazaki’s weirdest little guys yet — bubblelike spirits in a strange magical land who rise up to the heavens to be born (assuming they don’t get eaten by pelicans on the way).

With so many weird little guys running around Miyazaki’s filmography, it seems time to honor and celebrate them. Not every creature in a Miyazaki movie is a weird little guy. We love Totoros of all sizes and we had a fox-squirrel pet of our own, like Nausicaä’s Teto. But those are individual creatures. A key aspect of Miyazaki’s weird little guys is how numerous they are. They’re a swarm, frequently providing little moments of comic relief as they move coal or swim through the sea. Their designs are quite simple, but their meaning frequently is not.

Susuwatari (Soot Sprites)

Appear in: My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Spirited Away (2001)

What are they? The susuwatari, or soot sprites, have the distinction of appearing in not one but two Miyazaki movies, though they’re a bit different between My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away. In the former, they’re little more than black little poofs of soot with big eyes who float and scurry around the country house that Satsuki and Mei move into. Skittish and fond of shadows, Totoro’s susuwatari are a charming, harmless (if a little dirty) supernatural pest.

In Spirited Away, the susuwatari are hard workers, as they’re responsible for throwing coal into Kamajī’s boiler that powers the whole bathhouse. They’ve got little arms and legs and they’re much stronger than they look, as each is able to carry a lump of coal that Chihiro struggles to lift. (When she does so, they then all try to get out of doing any more work until Kamajī threatens to undo the spell that animates them, turning them all back into soot.) They also keep Chihiro’s shoes and clothes clean and safe when she doesn’t need them.

What do they mean? In My Neighbor Totoro, the susuwatari are the first sign that something magical is happening. They’re an entry-level supernatural occurrence and one that nicely parallels the real imaginings and, to some extent, fears that a young kid like Mei might have when moving into a big new house. In Spirited Away, they’re put to work in adorable fashion, perhaps reflecting the bathhouse’s purpose as a complex business rather than a sleepy countryside retreat.

How weird and little are they? Quite.

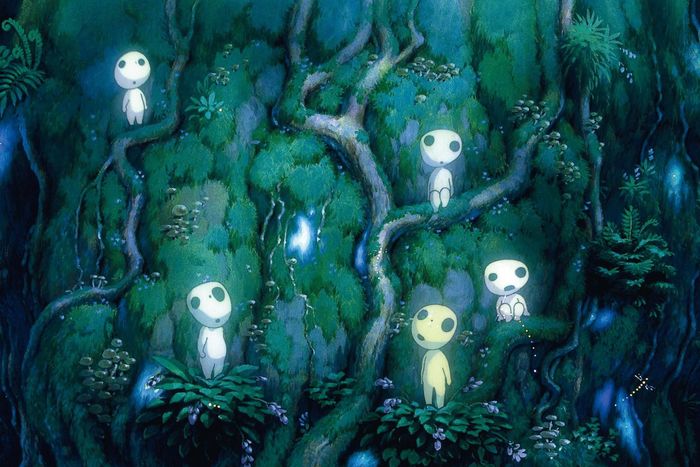

Kodama

Appear in: Princess Mononoke (1997)

What are they? Whereas susuwatari were a Miyazaki invention, kodama are a part of Japanese folklore, predating Princess Mononoke by centuries. They’re spirits that inhabit trees, and Miyazaki reimagines them as “children of the forest.” The sight of kodama, with their wee bodies and misshapen, simplified heads with just three black spots for a cute little face, is an indication that a forest is healthy. They’re childlike, imitating Ashitaka as he carries an injured man on his back and clicking their heads before joyously riding the windy treetops when the Forest Spirit transforms into the Night-Walker.

What do they mean? The kodama might have the most explicit meaning of any of Miyazaki’s weird little guys, as they represent wild forests and nature as it once was. In a rapidly changing Japan, such forests and their ancient, magical trees are increasingly scarce. When the Forest God is shot, kodama fall from the trees, a clear sign that mankind’s ambitions are destroying the natural world. And yet, the film ends with a moment of grace. As the land begins to heal, we see the reemergence of one kodama. The forest will never again be what it once was, ruled by gods and inhabited by oversize talking animals. But, nature can — and should — endure.

How weird and little are they? Profoundly.

Ponyo’s Sisters

Appear in: Ponyo (2008)

What are they? Like Ponyo, her (many) younger sisters are goldfish, albeit of the somewhat magical variety because they’re the children of the sea goddess Granmamare and ocean sorcerer Fujimoto. They’re very helpful, schooling around Ponyo and helping her to escape to the human world. When Fujimoto’s potions spill into the water, they transform into gigantic, more realistic fish as the oceans go haywire. Thankfully, they return to normal at the end of the movie, preserving their weird-little-guys status. (For the purposes of this list, “guys” is gender-neutral.)

What do they mean? In addition to being adorable and a little off-putting (that is quite a quantity of fish!), Ponyo’s sisters represent both the results of Fujimoto’s strict parenting and the unbridled, wild power of the ocean. They’re also a nice comparison to what Ponyo, the eldest sister, should’ve been had she not developed a love of ham and a desire to go to the surface world.

How weird and little are they? Extremely.

Warawara

Appear in: The Boy and the Heron (2023)

What are they? By far the blobbiest of all Miyazaki’s weird little guys, warawara live inside the magical reality Mahito travels to in the hopes of rescuing Natsuko, his aunt turned stepmother following his own mother’s death during the firebombing of Tokyo. Their purpose, with the help of Kiriko and a young woman named Himi with magical fire powers, is to float up to Mahito’s world where they will be born. In other words, they’re souls, waiting for a chance to live — unless pelicans eat them on the way up.

What do they mean? The Boy and the Heron is one of Miyazaki’s most loaded works, simultaneously pretty overt in its central metaphor and also dazzlingly complex and nuanced. At its core, though, is the sad, joyful nature of necessary change and the grief that comes with it. Mahito must overcome the loss of his mother and accept Natsuko (and the younger sibling she carries in her belly). The fall of imperial Japan, similarly, was a traumatic but necessary loss in order for a better, brighter future to begin. The warawara, as new life waiting to be born, are a clear metaphor for this. And, it is no accident that they’re being preyed upon by pelicans, who seem to be this magical land’s equivalent of the airplanes that are so destructive despite their beauty — connecting the warawara to The Wind Rises, by far Miyazaki’s least weird-little-guy-having feature.

How weird and little are they? Yes.

Parakeets

Appear in: The Boy and the Heron (2023)

What are they? This one is kind of a cheat, because while the colorful parakeets inside the tower are indeed numerous and very weird, they’re not little — at least not while they’re inside the tower. Thanks to its magic (and corrupting influence), these once-normal birds have become a society of humanlike, human-size birds that love fascism and also eating human flesh. But, when they leave the tower, they turn back into normal birds. So they can be weird guys or little guys, but not both at the same time.

What do they mean? They’re the silliest fascists you’ll ever see, but the parakeets pretty clearly represent the militarist traditions and ethos that is rotting the magical world (and by extension imperial Japan). They need to return to nature, in this case once again becoming normal birds. They also poop a lot, which is a whole subject on its own.

How weird and little are they? Debatably.