The 73-year-old Japanese animation titan Hayao Miyazaki says The Wind Rises is his final film, and if that’s true — we can pray it ain’t so, but he doesn’t seem the type to make rash declarations — he’s going out on a high. The movie won’t, I’m afraid, appeal to kids the way Ponyo or Spirited Away or My Neighbor Totoro does. It’s monster-, ghost-, and mermaid-free. It centers on grown-ups and is gently paced — maybe 15 minutes too long, I’d say, but you can forgive those longeurs when the work is this exquisite. It’s romantic, tragic, and inexorably strange, a portrait of a young Japanese man who dreams of creating flying machines and the Imperial Empire that funds his research. His country will take those machines and send them off to rain death and destruction on its enemies — but that’s not something to which the young designer gives too much thought. It’s not part of the dream of flight.

The young man’s name is Jiro and he’s a composite of an engineer named Jiro Horikoshi and aeronautical designer Tatsuo Hori, who wrote a novel called, also, The Wind Rises. From an early age, Jiro pores over drawings in English-language aeronautical magazines and communes in his fantasies with an Italian visionary called Caproni. There’s only a whisper of distinction between so-called reality and dreams that literally take wing. In the English-language version released by Disney, Joseph-Gordon-Levitt voices Jiro; and in his visions he stands on the wing of a plane under pink and gold cumulus clouds and alongside his Obi-Wan Caproni (voiced by Stanley Tucci).

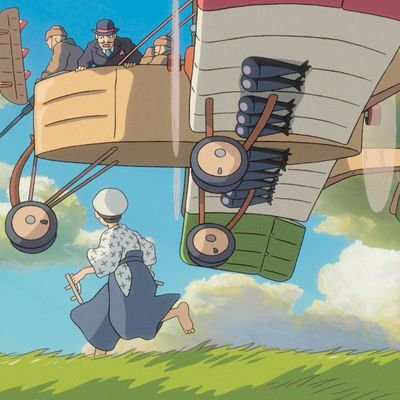

The machines he designs look like mechanically enhanced birds — there’s barely any border between objects that are natural and engineered. Jiro’s chief blueprint is inspired by the curve of a mackerel bone; he takes his cues from living creatures. Miyazaki has given us living machines before, among them the mythical bus in My Neighbor Totoro, but here they’re a mix of organic and inorganic. Jiro designs their endoskeletons with a slide rule and mathematical equations, but there’s a kind of alchemy, too. Everything is invested with spirit: levers, flaps, and, of course, the wind.

The title is from poet Paul Valéry: “The wind is rising, we must try to live.” It’s the Buddhist carpe diem — go with the flow. That wind carries off the parasol of a fragile girl, Nahoko, voiced by Emily Blunt, into the hands of Jiro — who’ll fall in love with her. Their love is idealized, but what an ideal. Though she is obviously dying of TB, she continues to move forward — into the wind.

The movie’s central contradiction is between the purity of Jiro’s dreams and the deadly uses to which his planes are put. Does Miyazaki downplay the evil? Some critics say yes. One even stopped an awards meeting of a Boston critics society to say that anyone who voted for the movie was accepting the whitewash of atrocities. I don’t see it that way. Miyazaki’s irony isn’t as broad as, say, Brecht’s in Galileo, the tragedy of a man whose appetite for science and lack of regard for its consequences lead inexorably — in Brecht’s formulation — to weapons of mass destruction. But it’s hard to imagine Miyazaki being that on-the-nose. The terrible implications are there, but underplayed.

It’s the underplaying — the plainness, the evenness of tone — that’s the key to his greatness, the way he transforms mundane sensations from real to surreal in barely perceptible puffs. In his hands, even simplified anime faces seem less bland than pared down to their essentials. He makes the human spirit seem as fleeting yet eternal as the wind itself.

*This article appears in the February 24, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.