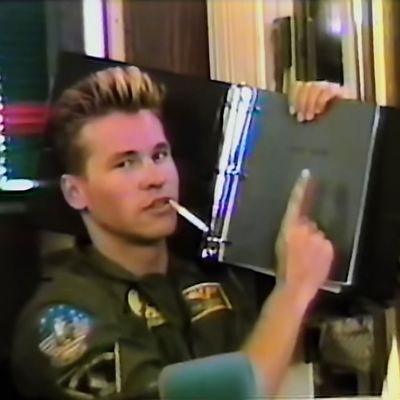

Val Kilmer was the first person he knew who had a video camera, and he has been recording his life for the past 40-plus years. As an actor, he appears to have carried his camera everywhere: the backstage dressing rooms of the early 1980s, where fellow up-and-comers like Sean Penn and Kevin Bacon would moon his lens; the drunken parties and trailer gab sessions of Top Gun, during which he and his pals playfully conspired against their co-star Tom Cruise; and the famously troubled set of The Island of Dr. Moreau, where Kilmer clashed with veteran director John Frankenheimer but got to act opposite his idol, Marlon Brando, even though by that point, Brando was clearly a shell of a shell of what he had once been.

This footage forms the backbone of the new documentary Val, which clocks in at just a little over 90 minutes. I’m not lying when I say that I would have happily watched 36 hours of Val Kilmer’s home movies. He seems to have the great documentarian’s nose for sticking his lens where he shouldn’t, and he has a decent eye, too. As it is, the footage of these shoots in Val (directed by Leo Scott and Ting Poo) consists mostly of tantalizing snippets, intercut with glimpses of his life over the years: his audition tapes, his acting classes, his marriage to Joanne Whalley, his divorce from Joanne Whalley, conversations with his now-deceased parents.

The years fly by like pages in the wind, and that’s sort of the point. Val shows us Kilmer’s past while following Kilmer in the present. A bout with throat cancer has robbed him of much of his voice, and he has to press a button on his throat to speak. But he persists, hopping from fan convention to fan convention, working on the paintings that are his current passion, and spending time with his grown kids. As an actor, Kilmer has to live with the image of what he once was, and it’s not exactly easy. At a special outdoor screening of Tombstone in Texas, he gets frustrated that he can never escape these old movies. Then he hears the crowd’s cheers and feels their love, and he is moved. He’s like a prisoner who has to find ways to free his spirit.

That tension between Val present and Val past captures the imagination, because Val past wasn’t exactly a fixed object. Those of us who watched Kilmer back in the day didn’t always know what to make of him. In his heyday, he was never really a leading man; he was more like someone’s idea of a leading man, with his blond hair, strong jaw, big teeth, full lips, and confident blue eyes. But he often gave great performances, especially in parts that played with that idea. He’s perfect as the dim-bulb Elvis clone in Top Secret! Those engineered-in-a-lab looks were just right for Iceman, the Über-mensch pseudo-antagonist of Top Gun. And what’s left to say about his turn as Chris Shiherlis, the romantic second banana to Robert De Niro’s master thief in Heat? His face busted up, he gets the movie’s emotional climax when his wife, played by Ashley Judd, waves him away from a police ambush with the slightest of hand gestures, simultaneously saving his life and destroying him forever. That was Val Kilmer at his best, a golden god rough and ruined.

Kilmer’s performances got more interesting and compelling as he aged and grew more weathered, so it’s doubly tragic that his medical problems prevented him from working regularly as an actor. At the time of his illness, he was traveling the country doing a one-man show as Mark Twain, a dream project of sorts that he still hopes one day to turn into a film. Kilmer seems healthy today — busy and energetic — but the specter of mortality hangs over the film. Val’s younger brother, Wesley, who was the mastermind behind most of their youthful cinematic shenanigans, died suddenly at the age of 15, and it’s clear that the actor, who was at Juilliard at the time, never really recovered from the loss. (Who would?) At one point, an older Val starts to feel ill after a day of signing pictures at a convention and has to step away and vomit. He is whisked away in a wheelchair to a room to sleep it off. As the camera continues to document all of this, we also see home-movie images of the young late Wesley, almost as if a curtain is being slightly parted into the Great Beyond. Kilmer tells us at one point that he was drawn to Twain’s story partly because of the family grief the author suffered later in his life. Death, it seems, is never far from his mind.

For all that, Val is not a gloomy movie at all. Quite the opposite. It’s vibrant, quick, and alive, and Val Kilmer today makes for an entertaining guide, with his hammy facial gestures now doing double duty since he can’t talk. He also, weirdly, narrates the film: His son, Jack, reads his father’s words in his father’s voice, which creates an extra layer of reflection to the movie, an extra layer of elusiveness. Jack Kilmer sounds a lot like Val Kilmer, but the fact that he isn’t Val Kilmer adds to the slippery nature of the subject. Who is Val Kilmer? Val doesn’t really know. Maybe, the film suggests, being alive simply means being undefinable.

More Movie Reviews

- The Accountant 2 Can Not Be Taken Seriously

- Another Simple Favor Is So Fun, Until It Gets So Dumb

- Errol Morris Has Been Sucked Into the Gaping Maw of True Crime