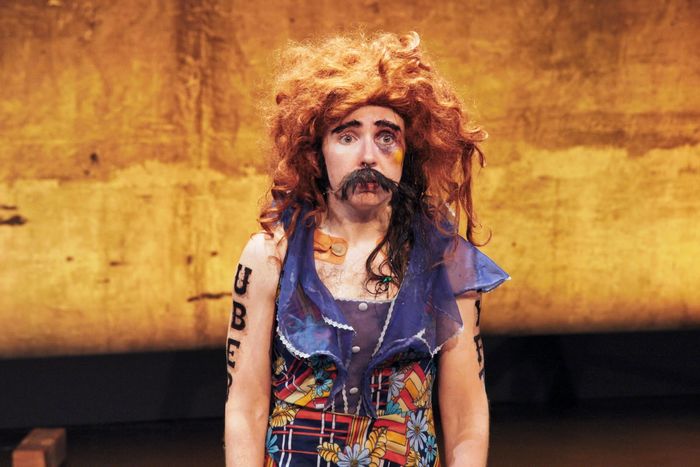

Nate begins with a silly, excessive, gooberishly stereotypical display of masculinity. Nate comes roaring onto the stage on a motorcycle amid a shower of pyrotechnics, before ditching the motorcycle and playing air guitar on a sheet of plywood with a giant dick spray-painted on one side. He chugs protein powder and then sets it on fire. He’s wearing a fleece-lined buffalo plaid jacket but he’s shirtless underneath, covered in dark, fuzzy chest hair and sporting a prominent, colorful black eye. It’s all clownishly big and also absurdly too small. The motorcycle is miniature. The protein-powder stunt is impressive and then immediately awkward, as Nate chokes on the gross shower of inhaled particles. It is a glorious display of overinflated maleness, punctured at every moment by how dumb it all is, and also by the fact that Nate is played by his female creator, Natalie Palamides.

Palamides’s “One Man Show” Nate, now an hour-long Netflix special, is unlike the familiar form of an hour-long comedy show. Netflix attempts to warn the audience about this with a short intro section of audience responses and a few comments from producer Amy Poehler, but you should ignore that intro entirely. It’s much less careful and thoughtful than the painstaking groundwork Nate himself lays.

Palamides is in character throughout the hour, and most of it follows the gradual development of Nate’s story, which unspools slowly amid his boisterous stunting and interactions with the audience. It’s full of jokes and often overwhelmingly funny, but Nate is perhaps more interested in creating discomfort than it is in letting its audience release that discomfort through laughter. There are swerves and surprises, and Nate shifts between sections where Palamides addresses the audience directly, and parts where she’s acting out Nate’s experiences. Nate is always aware of his audience, though — always conscious of himself as a performer, and always explicitly considering how his audience sees him.

That consciousness is not only a meta-awareness; Nate is not just a dude (played by a woman) standing on a stage and saying, “So here I am on a stage.” He is constantly asking the audience to help him create this story, to jump into the roles of people Nate knows, to come out onto the stage and enact this performance with him. In a more typical stand-up show it’d be “crowd work,” but here it’s something more like a crowd partnership, a compact with the viewers. Everyone sitting in the theater has to engage when Nate engages them, or at least has to voice their desire to not engage. It’s a dance of consent, a playful but intense demonstration of how theater requires the consenting participation of the audience as well as the players.

It begins in some small and fairly straightforward ways. Nate pulls a guy onstage as part of a motorcycle stunt. He goes up to people in the audience, looks straight into their eyes, and asks, “May I?” while miming a gentle groping gesture. If they say no, he backs off. They’re opening salvos in Nate’s intertwined twin projects, consent and performance. Palamides is needling them on the subject of consent, presenting the audience with a clear, black-and-white image of what a consensual encounter looks like. She’s also asking them to help her construct Nate, because the show can’t proceed without audience members who’ll be willing to play along, and Palamides’s exploration of consent doesn’t work without an audience there to say yes or no.

Consenting participation with Nate is not easy or comfortable, which is part of the point. Nate is a laughable buffoon and an uneasy scene partner, and not just because Palamides is the only one who knows what’s coming. But the spell works, and it works remarkably well. Eventually, after testing and prodding various audience members, Nate stands onstage, wet and nude (and sporting a distractingly large and springy rubber penis). He’s had a rough time of it lately, and he’d really love to have a conversation about it with his best friend Lucas. “Hey, Lucas!” he yells. He waits for a minute, and there’s silence. “Hey, Lucas!” he yells again. By this point, Nate has prepped his audience well. “Hey, Nate,” a random audience member replies, and the show continues with this new participant in the story along for the ride.

Part of the experience of Nate is sitting through these toss-offs to the audience, and living with the sudden discomfort of realizing the ball has been lobbed into your court. When I saw the show live earlier this year, it was at a much smaller theater than the one the Netflix special was filmed in, and the intimacy of the space meant there were fewer volunteers to play along with Nate’s show. People shifted uneasily in their seats, but Palamides was cheerful and relentless. She had to shout “Hey, Lucas!” for what felt like an unbearably long time, but finally a guy a few rows away relented. “Hey, Nate,” he answered, a little chagrined.

That intentional unease is crucial to what makes Nate work, especially as Palamides eventually steers the show into the area most viewers will immediately think of when they hear “it’s a show about consent.” When I heard that Nate was being filmed, my concern was that the camera would distance an at-home viewer from that crawling sensation of sitting in the audience and wondering if Nate was going to pick on you. The play of consent would feel less immediate and less urgent. It does, a little, but it also matters less than I feared it might. As it turns out, the sense of identifying with the audience members in Nate’s theater is strong enough that the experience translates well. It’s helped by the hyperpresent, dynamic camera work onstage, too — in more than one instance, we can see the camera following along with Nate’s antics, and Palamides works them into the act (by humping them, of course).

I don’t want to describe the rest of Nate with much detail. There’s a lot of pleasure in riding the shocks and twists as they arrive, and I’d hate to flatten too much of the careful ambiguity Palamides layers into the overall experience. But it’s not a show that diminishes with repeated exposure; it’s worth experiencing the surprises the first time through, and it’s also worth going back and sitting with them a second time. Because it feels like big, heady, serious stuff, and it is! It is an hour-long show about some of the biggest, trickiest ideas around — consent and performance, but also gender and pleasure and the nature of art — but it’s also delightfully dumb, just a big, loud hour of feelings and insecurities and dicks. Nate is a festival of big, stupid jokes that happen right alongside a really rich, open-ended examination of hard, serious questions.

At the end Nate asks a question and invites the audience to respond. I don’t know what the answer to it is, and Nate doesn’t either. But Nate is a weird, remarkable journey to the end point of being able to ask that question. What the audience does with it next is up to them.

This review was originally published on November 25, 2020.