When Joey Clift was growing up, he adored comedy but assumed it was a world in which he’d never be welcomed, because he rarely saw Native American communities like his own represented onscreen. Thankfully — and partially due to receiving “the right compliments,” he says — Clift moved to Los Angeles 11 years ago to pursue a comedy career anyway. He has fought for Native representation by organizing events like the Upright Citizens Brigade’s first-ever showcases for Native comedians in 2018 and 2019 as well as partnering with Comedy Central and IllumiNative for Indigenous Peoples’ Day in 2020 to spotlight fellow up-and-coming funny Natives. “For me, it’s just extremely surreal to go from wanting to do comedy but not thinking that I was allowed to — because there were no Natives doing comedy on a national stage — to having a chapter about me in a book about Native comedy,” he says. “That’s personally nuts.”

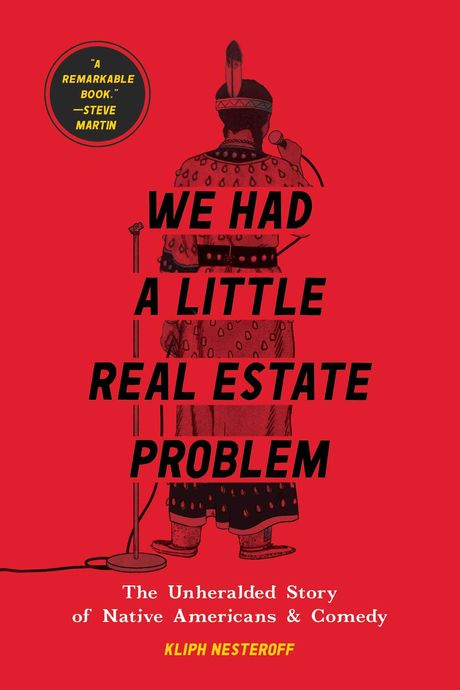

Clift is referring to Kliph Nesteroff’s new book, We Had a Little Real Estate Problem: The Unheralded Story of Native Americans & Comedy, a fascinating history of Natives in comedy and Hollywood, from Will Rogers to Charlie Hill to the sketch group the 1491s to the three comedians who joined Nesteroff for a long chat with Vulture. Alongside Clift (Cowlitz), Adrianne Chalepah (Kiowa/Apache of Oklahoma) and Jackie Keliiaa (Yerington Paiute and Washoe) recently connected over Zoom to discuss the book, what it’s like to be a Native comedian, and their thoughts on Native representation in comedy today and in the future. Below, an edited and condensed version of their conversation.

What Is Native Comedy?

Joey Clift: I’m sure Jackie and Adrianne have gotten this question a lot, and I’ve gotten this question a lot: “What is Native comedy?” And Kliph, since you’ve written an entire book about the history of Native comedy, if you could tell us what Native comedy is, so that I can better explain it to people, that would be hugely helpful.

Kliph Nesteroff: That’s funny, because when people ask me that question, or when journalists ask me that question, I say, “Don’t ask me — ask a Native person. I’m not the person to ask.” But really, my answer is: Native comedy is comedy that is done by a Native person, period. That’s all it is.

J.C.: There we go!

K.N.: I mean, you don’t ask me “What’s white comedy?” I guess you could have a scholarly discussion about Native humor and what that means, but I don’t address that in the book. I focus on the showbiz angle more than the cultural angle. I felt it was a weird project to take on, because I’m not Native. So I kind of focused on the showbiz and representation — or lack of representation — or historic representation in Hollywood, because that’s really more what I can speak to.

J.C.: Adrianne and Jackie, when someone asks you what Native comedy is, how do you answer that question?

Adrianne Chalepah: I usually say “I don’t know,” and I think that I’m confused with it myself, because I’ve debated different scenarios in my life about “What is Native?” And that is like the million-dollar question, at least within Indigenous communities at this moment. There doesn’t seem to be a consensus, and I love that, because it just demonstrates how diverse we are — that there is no singular definition — and that’s okay.

Jackie Keliiaa: Whenever someone asks “What is Native comedy?,” I immediately think, What’s Native humor? We all kind of have a general understanding of what Native humor is, like for ourselves, and there is a general thread, I think. I was just talking to Bobby Wilson from the 1491s and writer on the upcoming Rutherford Falls and Reservation Dogs. We talked about teasing and how that’s such a thread in all of our family experiences on the Native side. So I feel like when I’m talking to other Native people about what Native humor is, I have kind of an understanding of what that looks like. Because it is different from the sets that I’ve performed for San Francisco audiences, when there’s no Natives in the audience. I have more or less two different sets, and recently, I would say — in the pandemic — I started to put them together. I would have people in the audience that are Native and people in the audience that are non-Native, and I try to find those edges that work for both of them.

But to Adrianne’s point, it’s just so different. Adrianne and I are both comics, and we’re both Native, and we’re both women, but our stage experience is completely different. I totally admire what Adrianne and the Ladies of Native Comedy have done; I would always be like, Oh, man, I want those sets. But here in San Francisco, in the Bay Area, where I started stand-up, it’s a totally different landscape. Native comedy is happening everywhere. It’s at the wellness conferences. It’s at the casinos. It’s at the UCB in L.A. Native comedy is all things at all times. So it’s pretty exciting that it’s just this big nebulous form, and it’s really any Indians who are doing any Native comedy.

J.C.: I definitely feel like rez comedy is a thing. There are rez jokes — jokes about snags, and things like that, that are rez references that do well in rez rooms. I posted a video on Twitter recently where I ate $200 of Olive Garden lasagna like Garfield and filmed it. Now whenever anybody asks me what Native comedy is, I’m like, “I don’t know. It’s eating lasagna with your bare hands like Garfield. I’m Native, and that’s comedy, so I guess that counts.”

On Visibility

J.C.: I think that there’s a real thing about crab-bucket mentality, in that oftentimes when you’re a member of a marginalized group, it feels like there’s only one opportunity for members of that marginalized group. There’s a lot of, in any marginalized community, kneecapping of other people in the hopes that that will mean you’ll get those opportunities or whatever.

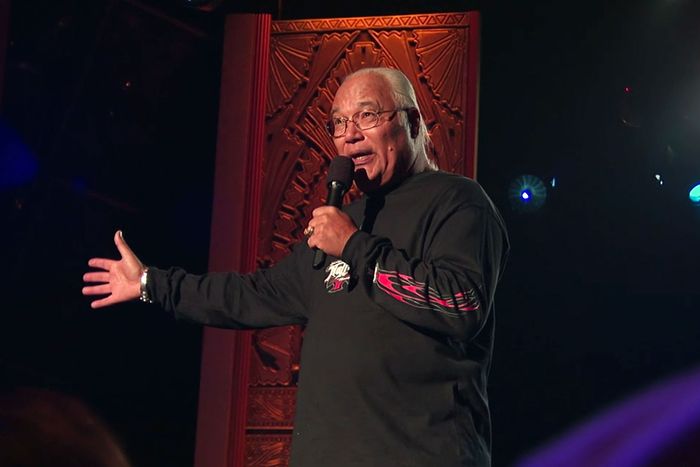

I talked to a couple of friends about this, specifically with Charlie Hill, about how I feel like he was a guy that built a really encouraging Native comedy community. In the late 2000s, he put together a Native stand-up special on Showtime that featured a lot of really great Native comedians. And everybody that I’ve talked to that’s met him prior to his passing say that he was the nicest and most important guy when it comes to Native comedians.

I definitely think that this is my experience of the Native comedy community now. We’re all hopefully friends and trying to help each other out and boost each other up. That kindness and generosity to each other is definitely built on a road that Charlie Hill laid over the past couple of decades of trying to boost up Native folks.

K.N.: Adrianne, correct me if I’m wrong, but it sounds like the model of encouraging other women to get involved in stand-up with the Ladies of Native Comedy was inspired by Ernie Tsosie being generous with you, right?

A.C.: Yes, definitely, because I had mentors. That’s something that a lot of people may not always get when pursuing comedy, and I was completely welcomed into the group, 49 Laughs Comedy, and it was Ernest David Tsosie who was the first person who gave me a chance. And he did it with such kindness that it really did model for me that there wasn’t this feeling of There’s only enough room for X amount of us. It was the opposite. He admitted, “We need more women voices in this space.” And I was like, “Shoot, just give me a chance, and I’ll try.” They were all just so nice to me that by the time I felt confident enough in my own abilities, I was like, I have to start my own crew, because I wanted to be around more women, and that’s how I did it.

It’s like at a dance-off: You put yourself in the corner, and you’re just a “Native performer,” and then you can’t do non-Native gigs. I’ve had people suggest to me, “You should take your tribe off of your résumé, or change your last name, because you could pass as white.” It’s awful, because it always feels like it’s either/or: If you’re going to participate, and if you’re going to cross over into mainstream, you really need to get rid of your Indigenous signifiers, or then for everything, you’re just going to be Indigenous. I had someone tell me that. They were like, “They’re just going to put you in a box.” And I was like, “No, I don’t want to be in a box!”

J.C.: I definitely felt this weird conflict when I first moved to L.A. about including my tribal affiliation in my comedian bios and things like that. For the longest time, I didn’t necessarily include my Native side of my identity into my comedy writing. I would write a million sketches about Batman and zero sketches about things that I was passionate about. I wasn’t until about probably 2017 or 2018 that it really struck me: There are so few Natives in the media. It’s important that I put my tribal affiliation in this so that hopefully somebody going through the UCB performer page sees “enrolled Cowlitz Indian tribal member, Native American,” et cetera.

The reason that Kliph interviewed me for this book is I put together the first-ever showcase of Native American comedians at UCB in 2018, and I originally just did it because I knew so many funny Native American comedians who weren’t given opportunities in these mainstream comedy theaters. I was like, I’m the only Native to ever be in a house team at UCB, so I’ll use that to help open the door to get all these super-funny Native American comedians in. And just by doing that, I got interviewed by probably a dozen different random outlets that were just like, “Natives doing comedy?!” And it really struck me just how needed it is.

K.N.: What’s interesting is when Charlie Hill and Larry Omaha put on that Showtime special, which aired at the end of 2009, there was none of that. They didn’t get phone calls from white media saying, “Natives doing comedy?!” It didn’t happen. That was just over ten years ago. They didn’t get a call. They got lots of bookings in Native nations and tribal areas, but they didn’t get a write-up in the New York Times, or in the L.A. Times, or any of that.

Sterlin [Harjo] says in the book, “There’s before Standing Rock and after Standing Rock,” and I wonder if you think that that is true in any way? Because it is interesting that Charlie Hill and Larry Omaha and all these guys had this prominent special on Showtime, which most Natives watched and enjoyed, and it didn’t really get any press from non-Native media at all. And then you did this show at UCB, and it got quite a lot of coverage.

So obviously there’s an evolution, or a shift, or a change happening. He might not be happy with me saying this, but I’ll say it here: When I was asked whether I would write this book or not in January 2018 by Simon & Schuster, I had another offer from a different publisher to do something completely different, and my agent thought I should have taken that and not this, because he didn’t see this book being of interest to anyone. It was before Rutherford Falls got green-lit. It was before Reservation Dogs went into production. It was before Jojo Rabbit won an Oscar and Taika [Waititi] did that speech saying, “Hey, there’s a place for you in Hollywood if you’re a young Indigenous kid.” That was just after Standing Rock.

J.K.: I think Standing Rock absolutely was a marker. I remember being like, Natives are on the news! No one ever put us on the news ever, but it was recurring coverage. But I think comedy is also changing. I think people are fucking tired of seeing the same shit every day, and it’s the same people. It’s the same archetypical white guy talking about the same thing. So I think that in tandem with a shift in Natives being in the media more, there are folks starting to be interested in different stories and different types of people that have always been here but just never got the opportunity to make something.

And to Adrianne’s point, when people were telling her to change her last name — never change your last name, by the way! I have a very distinctive last name, Keliiaa, and I make hosts say it correctly. In San Francisco, people are really good at it. There was only one person, and I will never forget her, who was like, “I’ll say Kelia.” And I was like, “Bitch, I’m never working with you again.”

But there’s a critique. Because of this shift in comedy, there’s a lot of salty-ass dudes who are like, “You’ve got a fancy last name, so now you’re going to get your gigs.” It’s back to that whole b.s. when people of color got into universities under affirmative action, and there were a bunch of haters that were like, “You don’t deserve that spot. You didn’t get that on merit.” There’s some people out there who think that if you have a distinctive last name, or think that if you have a distinctive point of view, and, in our case, being Indigenous people and sharing that experience in our work, that all of a sudden, we’re doing it because we want some “diversity” thing. No, this is just who the fuck I am. People are just tired of hearing you talk about Tinder.

I love that your origin story in comedy, Adrianne, was so supportive, because I would have liked that. But now I’m at a point where I’m like, Okay, I’ve gone through the gauntlet of what it is to be in comedy, and I’ve found my people, and I’m sticking with them, and I’m going to help support them, and they’re going to help support me. It’s a beautiful thing.

On Representation (or Lack Thereof)

J.C.: I think that it’s a bummer that there aren’t more Native comedians that are boosted up in the media. Just for example, I’m a huge fan of Conan O’Brien. Everything he’s done, from The Simpsons to Late Night to SNL, are major comedic influences for me and really just a big part of my comedy DNA. Conan has had probably thousands of comedians on late-night shows he’s hosted, but in his entire nearly 30-year career as a late-night-show host, he has never had a Native American comedian doing stand-up on his show. And since he’s wrapping up hosting a daily late-night show in a few months, there’s a good chance that he might go his whole career without showcasing a single Native American comedian.

This isn’t exclusive to Conan. A Native comedian hasn’t been given a stand-up slot on an American late-night TV show since Charlie Hill did Letterman in the mid-2000s, which was almost 20 years ago. To me, it creates a weird but unfortunate asterisk on the career of someone that I really look up to. My hope is that late-night-show hosts and bookers realize that the complete lack of Native talent on their shows is a huge blind spot for them. It’s cool that the history of Native comedy and Native stand-ups on late-night shows started with Charlie Hill in the ’70s, but it would be just a huge bummer if that history ended with him too. And now, almost 20 years after Charlie’s last late-night performance, today there are hundreds of Native comedians — a bunch of them are in this book who are funny, polished, and ready to be showcased — and we really just need an opportunity to knock it out of the park.

K.N.: Hopefully this book will change things. I hope it will make non-Natives who are oblivious more aware, because the most common comment I’m getting from white people is, “I didn’t know there was such a thing as a ‘Native American comedian.’” Like, every single day, I am hearing this. So maybe there will be a cause and effect where a stand-up booker will be more aware. I’m not trying to defend ignorance, but at the same time, I kind of understand the fact that people would be ignorant, because they’re not exposed to jack shit in the media. They’re not exposed to what they should be exposed to.

J.C.: I get that people have blind spots, and ultimately it’s easier to book comedians who you see at the Comedy Store or whatever. But I do think — and I think this is 100 percent to your credit — having a huge book about the history of Native comedians, with the names of a bunch of Native comedians in it who have super-funny Twitter accounts, Instagrams, et cetera, it kind of limits the excuses.

K.N.: This is so common in the history of Hollywood. Very early on, like the 1920s, when Natives were demanding jobs in Hollywood, they were like, “Oh, you’re making some shitty Western? Well, why don’t you hire all of these Indigenous actors instead of a bunch of white people?” The Hollywood studios would go, “Well, there aren’t any. We don’t know of any.” And there were all these organizations that formed and said, “No, here’s a list of 250 people and their tribal affiliations. So if you need Navajo extras, here’s 20 Navajo. No excuses anymore.”

J.K.: 2020 was a revolutionary year. 2020 really put a magnifying glass on the systemic racism that has been happening in this country forever. I mean, I loved watching montages of just Columbus statues being toppled and beheaded. It was beautiful. So we are dismantling systems right now, and I think for 2021, I hate to … You know what? I don’t hate to say it. It’s on them. If you don’t fucking book people, it’s on you. It’s not a blind spot. It’s the result of a system that you engage in, and you’re not going out there and looking. I’m tired of the onus being on us to constantly go, “Hey, we’re here! We’re here! We’ve got a book now. There’s glossy photos. We’re legitimate, right?” And it’s like, We’ve been here. I’m riled up!

A.C.: The burden of proving that we’re talented, that we exist, is always on our shoulders. So when we talk about systemic racism, the reason why we think this moment in time is so perfect is because you have people … Who is the comedian that pointed this out? They did a screenshot of the Chiefs at the Super Bowl and then above that is …

J.K.: That was Tai Leclaire. Amazing. So funny.

A.C.: It was so funny because he did the screenshot of the field during the Super Bowl — the Chiefs’ field that said “End Racism” at the top and then “Chiefs.” It’s hilarious to us, because it’s so fucking painful. It’s America saying, “We want to end racism, but not for Indigenous people. You guys wait and keep proving you exist.” You know?

It’s important, I think, to hold our role models in society accountable, because should we ever be in that position of having a powerful show, and having a powerful voice, I would hope that my team lifts up every rock and tries to find every voice that is being marginalized. And this is really why this book is such a big deal, because, yeah, no one’s really asked us what we thought about anything. I mean, they like to tell us how we feel, usually, and who we are.

It’s hard to make it in this country as an Indigenous person if you don’t come from wealth or a whole lot of privilege. I became a writer solely because I knew I would never see a role for me. A lot of comedians end up becoming writers too, because these roles just don’t exist for us; we need to create them. On the other hand, you have really powerful people who … It might be a blind spot, but if you’re making that much money and you have that much power, I think you have to ask yourself, On whose backs? Whose stories are not being told?

On the Future of Native Comedy

J.C.: 2020 was a nuts year as far as Native representation goes. We started the year with an NFL team being named after a legit racial slur referencing our genocide. We ended the year with two major sports teams changing their names, three Native TV shows in production, and the first time in the history of this country, a Native American woman is up to be secretary of the Interior, being in charge of Bureau of Indian Affairs, named Deb Haaland. For all of that to happen in seven months, six months, a year? One, that is 100 percent built on the backs of the work of everybody before us: the Standing Rock protesters, Charlie Hill, our ancestors who fought for recognition and stuff like that. But because we’re bearing the fruits that people worked legitimately hundreds of years for, I feel optimistic about the future of Native comedy. There might not have ever been a Native American comedian on late night in the past 15 years, but the future is bright.

A.C.: We also owe a great, great, great deal to Black Lives Matter.

J.K.: Absolutely.

A.C.: And we owe a great, great deal to the Black civil-rights activists, and Black people, because they lead the movement and the conversation for equality. As Native people, we directly benefit from Black people getting their freedom, and we should be standing side by side always and supporting our Black relatives.

K.N.: I feel like there’s been something percolating for the past couple of years, that there’s a snowball effect happening. People are still stupid, but I feel like there’s less stupidity? Or a little bit more information is getting out there. I also think that there’s been a little bit of an influence because of the internet connecting people. Indigenous communities around the world, really, are more connected now with the internet.

I don’t know if this will bode as a successful book or not, but I hope that it has some sort of impact in spreading awareness about the existence of Indigenous comedians and performers and all of those things, like you say, Joey, that should have been paid attention to a long, long time ago.

J.K.: And it’s not just existence. We’re fucking funny. At the end of the day, we’re so fucking funny. It’s a dream that we have the internet. That’s how I connected with Adrianne the first time. See, that’s the thing about Native comedy: It is all over. It is in urban centers. It is in rezes. It is out there.

J.C.: It’s on TikTok.

J.K.: Exactly. So because we’re so online now, in 2020, I got to perform with more Native people than I’ve ever performed with, because we didn’t have the distance issue. We were just able to get our time zones right, and we got a show together. That’s been the beauty of it. So, just in 2020, getting a chance to perform with so many Native comics, I was like, We’re so fucking funny. I’m so proud of us. We’re beautiful people. And we’re blowing up, y’all.

Nesteroff’s book We Had a Little Real Estate Problem: The Unheralded Story of Native Americans & Comedy is out now.